Part I: The Architectonics of Saadia’s System: A Rational Foundation for Divine Law

Saadia Gaon’s The Book of Beliefs and Opinions, written in 10th-century Baghdad, stands as a monumental effort to construct a rational edifice for Jewish faith in an era of intense intellectual ferment. Amidst the challenges posed by ascendant Islamic philosophy, Greek rationalism, and internal skepticism, Saadia sought to demonstrate that the revealed tradition of the Torah was not only compatible with reason but was its ultimate fulfillment. Treatise III, “On the Commandments,” is the keystone of this structure, providing a systematic philosophical justification for the entire corpus of Jewish law (mitzvot). It is not a mere codification but a profound argument for the law’s inherent wisdom, justice, and purpose.

The Foundational Premise: Divine Perfection and the Teleology of Law

The treatise begins not with a specific law, but with a foundational theological axiom that reorients the entire understanding of the human-divine relationship. Saadia asserts that the commandments are given entirely for the benefit of humanity, not for God. This premise derives directly from the philosophical conception of God as a perfect, self-sufficient being. A perfect being has no needs; therefore, human actions of obedience or worship can neither add to nor subtract from divine perfection. This initial move is a strategic masterstroke. By grounding the law in a principle of divine benevolence, Saadia preemptively refutes any critique that the commandments are arbitrary, capricious, or instruments of a tyrannical deity.

This reframing was radical in its context. It shifts the perception of the law from a system of appeasement or tribute paid to a monarch, to a divinely authored curriculum for human flourishing. The lawgiver is not a needy sovereign but a “benevolent architect” designing a system for the moral, spiritual, and societal well-being of creation. The purpose, or telos, of the law is thus established as pedagogical and therapeutic before any specific statute is examined. This transforms the entire relationship between God and humanity from one of a king and his subjects to that of a master artisan and a creation intended for perfection. This foundational move makes the entire system defensible on the rational and ethical grounds necessary to withstand the “intellectual heat” of the Baghdad academies.

The Central Innovation: The Epistemological Dichotomy of Commandments

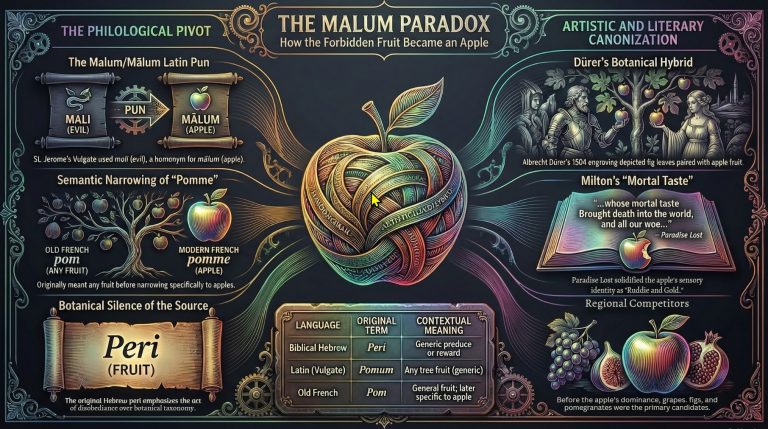

At the heart of Treatise III is Saadia’s celebrated division of the commandments into two distinct epistemological categories: the Rational and the Revealed. This dichotomy is not merely an organizational tool but a sophisticated framework for integrating universal reason with particular revelation.

The first category is the Rational Commandments, or aqliyyat. These are moral and ethical principles that human reason can discern and affirm independently, without the aid of divine revelation. They are considered universally applicable and self-evident, forming the necessary bedrock for any functional society. Examples include the prohibitions against murder, theft, adultery, and lying, as well as the positive obligations to dispense justice, show compassion, and, crucially, express gratitude to the Creator. Saadia argues that reason itself dictates that one owes thanks to the source of one’s existence. When God includes these laws in the Torah—for instance, “Thou shalt not steal”—it is not a redundant act. Rather, it serves to formalize, reinforce, and grant unambiguous divine authority to principles that fallible human reason might otherwise ignore, misinterpret, or conveniently set aside due to passion or self-interest.

The second category is the Revealed or Traditional Commandments, sam‘iyyât. These are laws whose specific details and rationales are not accessible to unaided reason and are known only through the specific content of divine revelation. This category includes the dietary laws (kashrut), the specific rituals of the Sabbath and festivals, and the laws of ritual purity. Reason might conclude that a day of rest is beneficial, but it could not deduce that it must be the seventh day or that 39 specific categories of work are forbidden. Saadia insists that these laws are by no means irrational or arbitrary; their wisdom is simply of a different order, serving functions beyond the immediate grasp of human intellect.

This dual classification serves as a powerful tool for engaging with the broader intellectual world. The category of aqliyyat creates a common ground with external philosophical systems, validating the power of universal reason and allowing Saadia to affirm the ethical conclusions of Greek and Islamic thinkers. It functions as a bridge, preventing Jewish tradition from being perceived as intellectually isolationist. Conversely, the category of sam‘iyyât serves as a boundary, delineating the unique, particular identity of the Jewish covenantal community. It asserts that while reason is a universal gift, it is insufficient for achieving the specific relationship with God and communal holiness prescribed by the Torah. This structure allows one to be both a philosopher and a faithful Jew, integrating universal truths with particular divine commands.

The Functions of Revealed Law: A Deeper Rationality

Saadia argues that the Revealed Commandments (sam‘iyyât), far from being arbitrary, are essential components of the divine pedagogy, serving at least four crucial functions that address the inherent limitations of unaided human reason. Taken together, these functions demonstrate that the revealed law acts as a comprehensive cognitive and social scaffolding, without which the rational law would collapse under psychological and social pressures.

First is Reinforcement. Revealed laws give concrete, actionable form to abstract rational principles. The rational duty of gratitude to the Creator, for instance, remains a vague sentiment until revelation provides specific prayers, blessings, and festival rituals that give it structure and consistency. The Sabbath rituals are not random acts but a divinely given method for enacting the rational principles of remembering creation and expressing gratitude. This function translates the “what” of rational ethics into the “how” of a lived religious life.

Second is Testing Obedience. This function addresses the limits of self-interested morality. Obeying the prohibition against murder is largely rational and self-serving, as it contributes to a stable society from which one benefits. Obeying a command whose rational benefit is obscure, such as a specific dietary rule, requires a higher level of commitment. It demands trust in the wisdom of the Lawgiver, cultivating humility and a faith that transcends calculated self-interest. This test is not for God’s information—an omniscient being has no need for it—but for humanity’s moral and spiritual development, building character and genuine piety rooted in trust.

Third is Preventing Error. Saadia, witnessing the conflicting philosophical schools of his day, understood that human reason is fallible, corruptible, and often swayed by passion and bias. Left to its own devices, reason can justify nearly any action. The revealed commandments act as a corrective, an unambiguous and divinely guaranteed standard. They provide a stable ethical core, an anchor that prevents individuals and societies from drifting into moral relativism or rationalizing away essential principles.

Fourth is Providing Specificity and Facilitating Community. Reason may be vague, suggesting a need for rest but not its specifics. Revelation fills in the blanks, making the general principle concrete and practicable. Furthermore, the shared observance of these specific practices—dietary laws, festivals, modes of prayer—binds a community together. It creates shared rhythms, a common discipline, and a collective spiritual identity, shaping a people consecrated to living according to a shared divine blueprint. This demonstrates a profound understanding that ethics are not actualized in a vacuum but require a communal context for their sustenance.

The Cornerstone of Justice: Free Will and Moral Responsibility

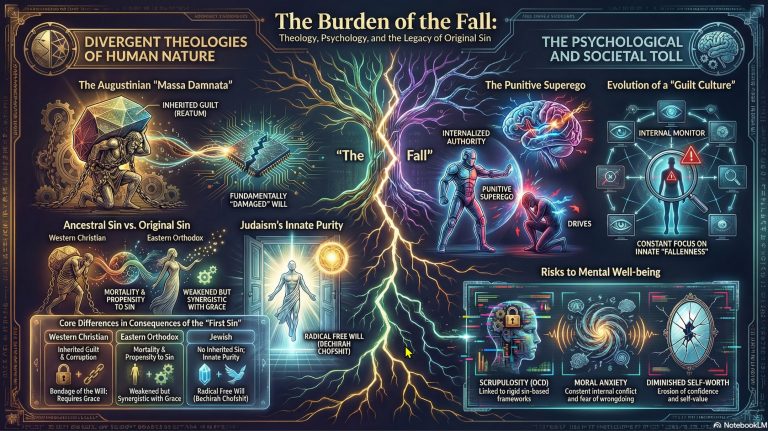

The entire edifice of Saadia’s system of law rests upon one final, indispensable cornerstone: human free will. Without it, the concepts of command, obedience, transgression, reward, and punishment become a meaningless charade. Saadia argues forcefully against the deterministic and fatalistic views prevalent in his time, insisting that the very structure of divine communication presupposes human freedom of choice.

His primary argument is grounded in the concept of divine justice. If human actions are predetermined, and individuals have no ability to choose otherwise, then a just God could not possibly hold them morally responsible. To reward someone for a good act they were compelled to perform, or to punish them for an evil they could not avoid, would be the height of injustice, transforming God into an arbitrary tyrant. Therefore, for Saadia, upholding God’s perfect justice logically requires upholding human free will. Moral responsibility vanishes without genuine choice, and the system of reward and punishment becomes nothing more than “meaningless cruelty”.

Free will is thus not merely another topic in the treatise; it is the logical linchpin that connects God’s nature to human action and makes the system’s purpose—the genuine, earned flourishing of the human being—achievable. It is the active ingredient that allows humans to be moral agents, capable of freely choosing to align themselves with the divine “instruction manual” for their own perfection. This closes the logical loop that begins with a perfect God who, out of benevolence, creates free beings and provides them with a just law so they may achieve their highest good.

The Critique of NotebookLM

Part II: The Modern Re-Framing: Saadia Gaon in the Digital Scriptorium

The transmission of a 10th-century philosophical treatise to a 21st-century audience necessitates an act of profound translation. The provided transcript of a modern dialogue offers a compelling case study in this process, deconstructing Saadia’s scholastic system and reassembling it using contemporary rhetorical strategies and metaphors. This re-framing is not simply a simplification but a significant hermeneutic act that reveals as much about the modern mindset as it does about Saadia’s original thought.

The Hermeneutics of Accessibility: From Treatise to Podcast

The podcast immediately establishes a narrative frame, casting Saadia as an intellectual hero in 10th-century Baghdad, defending tradition against “serious intellectual heat” from skepticism and rationalism. This framing makes him a relatable protagonist in a timeless drama of faith versus reason. The conversational, question-and-answer format further enhances accessibility, breaking down a dense philosophical system into digestible, dialogical segments.

The central organizing principle of this modern interpretation is the persistent question, “Why?”. The speakers ask: “Why do we need commandments at all?”; “If reason tells us not to steal, why did God bother…?”; “Why add this layer…of revealed laws?”. This interrogative stance contrasts sharply with the declarative, systematic structure of a classical philosophical treatise. Saadia’s work unfolds from axioms to conclusions, its authority residing in its logical coherence. The podcast, however, establishes its authority through a process of shared inquiry. It anticipates and voices the modern listener’s likely points of confusion and skepticism, making the audience feel like active participants in a journey of discovery. This reveals a fundamental shift in how knowledge is legitimized in the contemporary era. It is not enough for a system to be logically sound; it must also be persuasive and answer the existential question, “Why should I care?” The transcript does not merely present Saadia’s answers; it models a way of thinking that makes those answers feel relevant and earned.

The Power of the Metaphor: Translating Concepts Across Millennia

The most potent tool in this act of translation is the consistent use of modern, relatable metaphors to explain Saadia’s core concepts. A close analysis of these metaphors reveals a consistent pattern of re-orientation, shifting the philosophical framework from a theocentric to a more anthropocentric (human-centered) perspective.

The divine law as a whole is described as an “instruction manual for living well,” with God positioned as a “benevolent architect”. This powerful metaphor shifts the emphasis from legal obligation owed to a transcendent sovereign to practical, user-focused guidance for achieving personal well-being and flourishing. The law becomes a “tool,” not a “burden”.

The function of “Testing Obedience” is translated into the psychological concept of “building spiritual muscle”. Saadia’s original concept is primarily about the human-God relationship—a test of fealty and trust in the divine Lawgiver. The modern metaphor reframes this as an internal process of self-improvement and character development. The focus moves from an external demonstration of faith to an internal exercise in personal growth.

Finally, the function of “Preventing Error” is explained using the metaphor of an “anchor” or a “North Star”. Saadia’s argument addresses an objective epistemological problem: the fallibility of human reason when measured against a divine standard. The metaphor personalizes this abstract danger, translating it into the relatable, subjective experience of feeling lost in a “fog of debate or desire”. The law becomes a navigational tool that I use to secure myself against existential disorientation.

Across these examples, a clear pattern emerges. The original concepts, grounded in objective realities like God’s justice, the authority of revelation, and the structure of the law, are consistently translated into the language of subjective experience: personal growth, feelings of security, and the pursuit of a good life. This is more than mere simplification; it is a fundamental re-orientation of the system’s perceived value. The podcast makes Saadia’s philosophy compelling to a modern audience by framing it as a sophisticated form of spiritual psychology, suggesting that the contemporary search for meaning has shifted from understanding one’s place in a divinely ordered cosmos to optimizing one’s own internal state and personal journey.

Part III: A Synthesis of Perspectives: The Dialogue Between Past and Present

Placing Saadia Gaon’s formal philosophical system in direct dialogue with its modern, metaphorical re-framing produces a novel perspective. This synthesis reveals how the contemporary interpretation, while altering the primary emphasis, succeeds in uncovering and amplifying latent psychological and existential dimensions within Saadia’s original framework. The dialogue between the 10th-century treatise and the 21st-century podcast is not one of fidelity versus distortion, but a dynamic interaction that illuminates the enduring relevance of Saadia’s thought.

Conceptual Translation: A Systematic Comparison

The semantic and thematic shifts that occur in the translation from scholastic philosophy to modern discourse can be systematically mapped. The following table juxtaposes Saadia’s core concepts with their modern metaphorical counterparts, analyzing the nature of the transformation. This structured comparison makes the consistent pattern of re-framing—from the theocentric and legal to the anthropocentric and psychological—explicit and undeniable.

| Saadia’s Core Concept | Key Terminology from Treatise III (based on ) | Modern Metaphor/Framing from Transcript (based on ) | Analysis of Semantic and Thematic Shift |

| The Teleology of Law | “For humanity’s benefit and perfection, not God’s… an expression of God’s wisdom, justice, and benevolence.” | “An instruction manual for living well… a benevolent architect… a tool… for our flourishing, our moral health.” | Shift from a principle of divine benevolence (a statement about God’s nature) to a principle of user-centric utility (a statement about the law’s function for the individual). |

| Function: Testing Obedience | “A test of human faith and willingness to obey God’s will… demonstrates profound trust in the divine legislator.” | “Building spiritual muscle… cultivating humility… by trusting the process, even if the why isn’t obvious.” | Shift from a theological concept of demonstrating fealty and trust in an external Lawgiver to a psychological concept of internal self-improvement and character development. |

| Function: Preventing Error | “Human reason… is fallible… revealed commandments provide clear, unambiguous guidance, preventing… misinterpreting or neglecting rational principles.” | “An anchor or the North Star… when human reason gets lost in the fog of debate or desire… it cuts through the arguments.” | Shift from an objective epistemological failure (reason’s inability to grasp a divine standard) to a subjective existential experience of disorientation and the need for personal stability. |

| The Interdependence of Laws | “Both types of commandments are essential for human perfection… a divinely ordained path to human flourishing.” | “Rational law is the ethical bedrock… Revealed law builds on that bedrock, providing the specific structure, the discipline, the communal framework.” | The modern framing maintains the core idea of interdependence but emphasizes the architectural and structural role of revealed law in a way that resonates with modern systems thinking. |

| The System as a Whole | “A robust rational foundation for the entire system of Jewish law… a testament to God’s wisdom, justice, and profound care.” | “A carefully designed pathway, a guide towards our own flourishing, our moral and spiritual maturity… not meant to be chains.” | The overall framing moves from a defense of a divine legal system to the presentation of a personal pathway for spiritual growth, emphasizing freedom and flourishing over obligation and authority. |

What is Gained, What is Lost?: Evaluating the Modern Interpretation

This act of translation yields significant gains while also incurring certain losses. The primary gain is undeniable: accessibility and psychological resonance. The metaphorical framework makes Saadia’s thought immediately potent and existentially relevant to a modern audience that may be alienated by scholastic terminology and theocentric premises. It brilliantly highlights the immanent, lived benefits of the law—its power to shape character, provide stability, foster community, and structure a meaningful life. In doing so, the modern framing uncovers a profound psychological wisdom that is present, though less explicit, in Saadia’s original work.

However, this gain in psychological immanence comes at the cost of theological and philosophical precision. The intense focus on the individual’s subjective experience can obscure the transcendent framework that gives Saadia’s system its ultimate authority and meaning. The concepts of God’s absolute justice, the objective reality of the divine command, and the ultimate authority of the Lawgiver can become secondary to the therapeutic benefits the system provides to the believer. The polemical urgency of Saadia’s context—his arguments against Karaites who rejected rabbinic tradition, antinomians who claimed to have outgrown the law, and fatalists who denied free will—is softened in favor of a more universal, less historically-contingent presentation. The law as an objective, divine decree is subtly transformed into a subjective, spiritual resource.

The Uncovered Insight: Saadia as a Psychologist of the Law

The most significant outcome of this synthetic analysis is the realization that the modern, psychological re-framing is not a complete distortion of Saadia’s project. Rather, it is an amplification of a dimension that was always present but perhaps subordinate in the original text. Saadia’s detailed analysis of reason’s fallibility, its susceptibility to passion, the need for behavioral reinforcement through ritual, and the role of community in sustaining ethical life demonstrates a profound understanding of human nature. He was, in effect, a psychologist of the law. The modern metaphors of “spiritual muscle” and “anchors” are so effective precisely because they latch onto this implicit psychological architecture within his system.

This connection is perfectly crystallized in the final question posed by the podcast’s host: “Where’s the line?” between necessary divine guidance and rules that feel arbitrary to our limited reason. This question is the quintessential modern articulation of the central tension that animated Saadia’s own work. Saadia’s project was to demonstrate that the Torah struck a perfect, divinely ordained balance, and that even the laws opaque to reason were perfectly rational from God’s perspective. The modern listener, as voiced by the host, inherits Saadia’s respect for reason but lacks his a priori faith in the perfection of the revealed text. For the modern mind, the balance is not a given to be defended, but a question to be perpetually negotiated.

The modern interpretation, therefore, does not simply translate Saadia; it re-activates his core intellectual and spiritual project for a new generation. It demonstrates that his framework is not a historical artifact but a living model for grappling with the fundamental human quest to reconcile universal ethical reason with the specific, grounding commitments of a particular tradition.

Conclusion: The Enduring Resonance of Saadia’s Rationalism

Saadia Gaon’s Treatise III of The Book of Beliefs and Opinions stands as a remarkably robust and coherent philosophical defense of the divine commandments. Grounded in the theological premise of a perfect and benevolent God, it systematically argues that the law is a divinely provided pathway for human flourishing. Its central division of commandments into the Rational and the Revealed creates a sophisticated framework that both embraces universal reason and preserves the particularity of revelation, while its staunch defense of free will ensures the entire system is predicated on divine justice and human moral agency.

The analysis of its reception in a modern, conversational format reveals a significant hermeneutic shift. The 21st-century interpretation translates Saadia’s theocentric, legal-philosophical language into a predominantly anthropocentric and psychological one. Through the power of metaphor, concepts of divine authority and objective law are re-framed as tools for personal growth, spiritual discipline, and existential stability.

This act of translation, while sacrificing a degree of theological precision, is not a falsification. Instead, it successfully illuminates the profound psychological realism embedded within Saadia’s system—his keen awareness of human fallibility and the cognitive and social supports necessary for a virtuous life. Ultimately, the dialogue between the 10th-century text and its 21st-century interpretation reveals the enduring power of Saadia’s framework. It continues to provide an invaluable model for structuring the timeless and deeply human conversation between reason and faith, universal ethics and communal identity, and divine authority and the personal quest for a meaningful and flourishing existence.

References

Saadia Gaon – The Book of Beliefs and Opinions; Edited & Translated by Samuel Rosenblatt – Published Yale University 1976 (Republished org. 1948)

Google NotebookLM report ‘Critique’ transcript