1. Introduction

Moshe Idel stands as a towering figure in the contemporary study of Jewish mysticism, known for his prolific output and transformative analyses of Kabbalah, Hasidism, and Jewish intellectual history.1 His work consistently challenges established paradigms, often delving into neglected corners of Jewish thought and highlighting the interplay between mystical, magical, philosophical, and liturgical dimensions.3 Within this extensive body of scholarship, Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism occupies a unique position.1 Published in 2011, the book confronts a complex and often paradoxical historical and conceptual relationship: the enduring, multifaceted connection between the planet Saturn (known in Hebrew as Shabbetai) and various facets of Jewish identity, mystical speculation, and historical experience across centuries.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of Moshe Idel’s central arguments in Saturn’s Jews. It examines his exploration of Saturn’s dualistic symbolism, tracing its negative associations with malignancy, sorcery, and the controversial hypothesis regarding the Witches’ Sabbat, alongside its less frequent but significant positive links to redemption, messianism, and the pivotal figure of Sabbatai Tzevi. Furthermore, the report delves into the recurring theme of melancholy and its perceived connection to both Saturn and Jewish intellectual life. A crucial component of this analysis involves identifying the key textual sources—ranging from Talmudic passages and Midrashim to foundational Kabbalistic works like the Zohar and the influential Sefer ha-Peliy’ah—and the specific thinkers whose ideas Idel marshals to support his thesis. Finally, this examination contextualizes Idel’s work within the broader landscape of Jewish studies, incorporating scholarly reviews and critiques, paying particular attention to the book’s dialogue with the influential interpretive frameworks established by Gershom Scholem and the Warburg school of intellectual history.

The structure of this report follows a logical progression designed to unpack the layers of Idel’s argument. It begins by outlining Idel’s core thesis concerning “Saturnism” and his methodological reliance on the Warburgian concept of Saturn’s duality. Subsequently, it explores the negative and positive valences attributed to Saturn within Jewish traditions, focusing specifically on the proposed links to the Witches’ Sabbat and the Sabbatean movement. The analysis then turns to the theme of melancholy and its connection to the Saturnine temperament in Jewish intellectual history. Following this, the report details the primary textual and intellectual sources underpinning Idel’s study. A dedicated section addresses the scholarly reception of Saturn’s Jews, highlighting both its contributions and the critiques it has faced, particularly in relation to Gershom Scholem’s work. The report culminates in a synthesis that assesses Idel’s overall contribution to the understanding of the complex interplay between astrology, Kabbalah, Jewish identity, and historical consciousness.

An Audio Deep Dive

2. Moshe Idel’s Central Arguments and Methodological Framework

At the heart of Saturn’s Jews lies Idel’s exploration of what he terms “Saturnism”—the persistent, historically traceable belief connecting the planet Saturn specifically with the Jewish people.1 This connection finds its ancient roots in the astrological assignment of the seven known planets to the days of the week, designating Saturn (the seventh planet) as the ruler of the seventh day, the Jewish Sabbath (Shabbat).5 Idel meticulously traces the evolution and ramification of this core association through a wide array of Jewish texts and thinkers, demonstrating its enduring, albeit often subterranean, presence in Jewish self-perception and external portrayals from antiquity through the Middle Ages and into modernity.

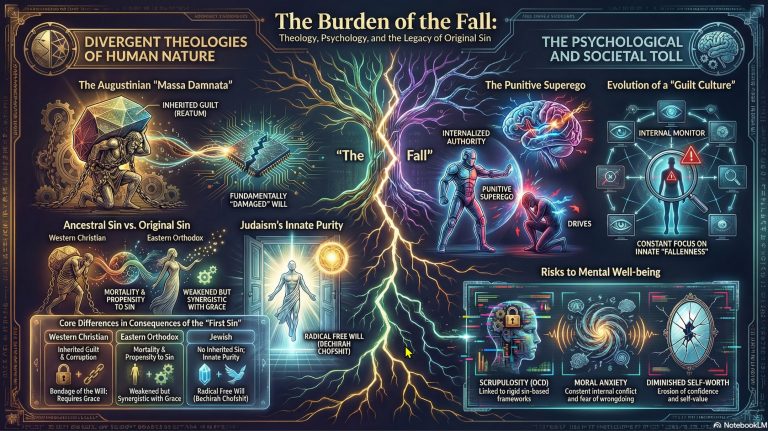

Crucial to Idel’s analytical approach is his adoption of a methodological framework heavily influenced by the Warburg school of research, particularly the seminal work Saturn and Melancholy by Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl.14 Following these scholars, Idel emphasizes the fundamental duality inherent in the symbolism of Saturn.5 This dual nature allows Saturn to be associated simultaneously with negative forces—misfortune, limitation, darkness, sorcery—and positive potentials—depth, contemplation, structure, and even redemption and messianic hope.5 Idel explicitly structures the core of his book around this dichotomy, dedicating separate chapters to what he terms, borrowing from Panofsky, Saturn’s “negative conceptual structure” and its “positive conceptual structure” as they relate to Jewish history and thought.5 This framework proves essential, providing Idel with an interpretive lens capable of accommodating the contradictory traditions surrounding Saturn without dismissing or minimizing either pole. It allows him to present a nuanced picture where Saturn’s influence on Jewish identity is neither wholly detrimental nor entirely auspicious, but rather a complex tapestry woven from opposing threads.

Idel argues that astrology, often viewed as marginal to mainstream Jewish thought, served as a significant historical channel for the transmission of ancient motifs and mythologoumena, including those with pagan origins, into the intellectual world of medieval Jewish elites.5 The adoption of the “astral order,” particularly through the influence of Greek philosophy mediated by Islamic culture, provided a new framework—a “new type of order”—for understanding and explaining aspects of Judaism and Jewish destiny in terms familiar to the broader medieval intellectual milieu.5 This process, which Idel refers to as part of the “naturalization” of Judaism, had profound repercussions for how Jews understood themselves and how they were perceived by others.5

Consequently, Idel’s focus extends beyond astrology as a discrete technical discipline. He is concerned with the broader “nebula of ideas” and the evolving “conceptual structures” that formed around the figure of Saturn.5 His analysis tracks how clusters of themes—Saturn, Sabbath, sorcery, Jews, Binah, messianism, melancholy—became intertwined, separated, and reconfigured within Jewish texts and consciousness over time.5 This approach aligns with the methodologies of intellectual history and the history of concepts, tracing the life of an idea (Saturn and its associations) across diverse historical and cultural contexts, rather than focusing solely on social history or the history of specific astrological practices. He investigates the dynamic interplay and resonance of these concepts, revealing how astrological symbolism permeated and shaped discussions on Jewish identity, religious practice, and eschatological hope.

3. Saturn’s Shadow: Malignancy, Sorcery, and the Witches’ Sabbat

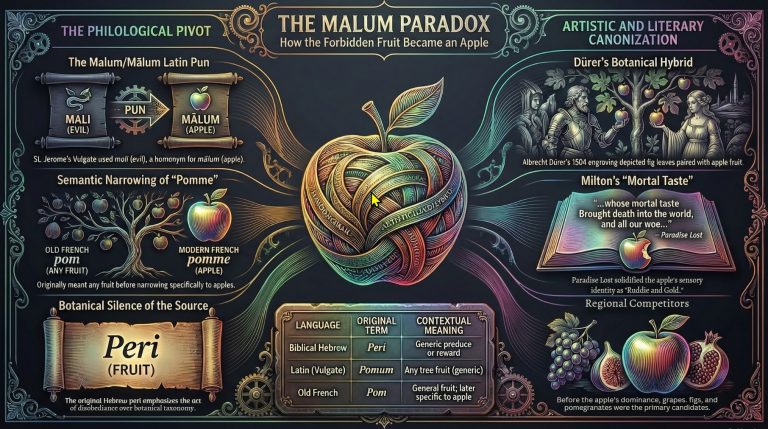

The association between Saturn and the Jews finds its bedrock in ancient astrological systems that linked the seven classical planets to the days of the week. Saturn, the seventh and outermost known planet (Hebrew: Shabbetai), was assigned rulership over the seventh day, Saturday, which coincided with the Jewish Sabbath (Hebrew: Shabbat).5 This connection was not merely an internal Jewish understanding; it was recognized by prominent Roman historians like Tacitus and Cassius Dio, as well as Church Fathers such as Augustine, who noted the special link between Saturn, Saturday, and the Jews’ holiest day.16 Jewish sources themselves reflect this awareness, most notably the Babylonian Talmud (tractate Shabbat 156a), which explicitly refers to Saturn as Shabbetai, “the star of Shabbat”.16

However, this astrological association carried inherently negative connotations within the dominant Greco-Roman and later Arab astrological traditions. Saturn was widely regarded as the most malevolent (infortuna maior) of the planets, associated with restriction, misfortune, coldness, darkness, old age, and death.16 Consequently, the astrological designation of Saturn as the planetary ruler of the Jews led to the perception, particularly among non-Jews, that the Jewish people were inherently influenced by Saturn’s baleful nature, prone to melancholy, isolation, and even sinister practices.16

Moshe Idel argues that this negative valence was not merely an external perception but also found resonance and elaboration within certain streams of Jewish thought, particularly among intellectual elites in Spain and Provence from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries. He identifies a recurring “negative conceptual structure” in which Saturn, the Sabbath, sorcery (or magic), and the Jews themselves become explicitly linked.5 Idel traces the emergence of this nexus, suggesting its first clear attestation appears in the work of the tenth-century Arab astrologer Al-Kabi’si (Alcabitius).9 This linkage intensified in later Jewish sources. Fourteenth-century texts by figures like Shlomo Franco and Shem Tov ibn Major explicitly refer to the demonic aspects of Saturn, reinforcing its negative associations.9 This trend continued into the fifteenth century, notably within the astrological worldview of the Italian Kabbalist Yohanan Alemanno.9 Idel’s survey indicates that while perhaps marginal within the totality of Jewish literature, this negative conceptualization of Saturn was a persistent theme within specific speculative and elite circles.9

Building upon this analysis, Idel advances his most provocative and debated hypothesis: a potential connection between this negative Saturn-Sabbath-sorcery complex within Jewish thought and the development of the European myth of the Witches’ Sabbat during the late medieval and Renaissance periods.1 Acknowledging that previous scholarship has failed to establish a convincing etymological link between the Hebrew Shabbat and the obscure term Sabbat used for the witches’ demonic gathering, Idel proposes an alternative pathway based on conceptual transference.9 He suggests that Christian authorities involved in constructing the witchcraft mythos may have encountered, misunderstood, or deliberately distorted the negative associations surrounding Saturn, the Jewish Sabbath (as Saturn’s day), and alleged Jewish involvement in sorcery found circulating among Jewish elites.9 This misunderstanding, Idel posits, could explain the otherwise puzzling terminological affinity between the holy day and the demonic rite. He carefully distinguishes his usage, employing ‘Sabbath’ for the Jewish observance and ‘Sabbat’ for the witches’ myth.5

To bolster this hypothesis, Idel points to certain parallels between classical Saturnian mythology and imagery, elements of which reappeared in medieval Jewish texts discussing Saturn, and the alleged rituals described in accounts of the Witches’ Sabbat.9 One example involves the accusation that witches consumed children, which echoes the ancient myth of Kronos/Saturn devouring his offspring. However, Idel himself concedes that this specific Saturnian motif has only a “vague” representation in Jewish literature.9 Another parallel concerns the prominent role of the goat as an embodiment of Satan in Sabbat lore; Idel notes a nexus connecting demons, Saturn, and goats found in some medieval Jewish astrological or magical treatises, such as the work of Shem Tov ibn Major.9

Despite the ingenuity of this thesis, scholarly reviews highlight its speculative nature. While acknowledging the originality of Idel’s attempt to bridge Jewish and non-Jewish conceptual worlds and agreeing that the idea merits further investigation, critics point out the relative scarcity of direct evidence linking the internal Jewish discourse on Saturn’s negative aspects to the external formation of the Witches’ Sabbat myth.9 Idel himself cautions that references to specific astro-magical rituals performed by Jews on the Sabbath are scarce in the philosophical and Kabbalistic sources he examines, making it difficult to prove widespread practice that could have been directly observed or misinterpreted.9 Most elements described in the learned discourse of witchcraft, reviewers note, can be more readily traced to established non-Jewish folk beliefs, demonological traditions, or long-standing anti-Jewish stereotypes (such as accusations of ritual murder or host desecration) rather than specifically to the Saturnian imagery found in late medieval Jewish writings.9 The proposal regarding the Witches’ Sabbat thus exemplifies Idel’s scholarly inclination to explore potential, even if unproven, lines of conceptual influence and resonance across cultural divides. It suggests an interest less in establishing definitive causality and more in mapping the complex ways ideas—and the fears or prejudices attached to them—can migrate and transform, potentially contributing to the formation of powerful cultural myths even through indirect pathways or misinterpretations.5

4. Saturn’s Light: Redemption, Messianism, and Sabbatai Tzevi

Contrasting sharply with the planet’s predominantly malefic reputation, Moshe Idel identifies a distinct, albeit less common, “positive conceptual structure” associated with Saturn within Jewish mystical and astrological traditions.5 In this alternative framework, Saturn transcends its negative connotations and becomes linked with concepts of hope, divine understanding, redemption, and messianism. This positive revaluation, Idel argues, played a significant, if often overlooked, role in shaping certain currents of Jewish thought, culminating dramatically in the context of the Sabbatean movement.

One strand of this positive association emerged within astrological speculation concerning messianic timelines. Some late medieval Jewish thinkers, operating within the shared astrological discourse of the period, interpreted major astronomical events, particularly the conjunctio maxima—the great conjunction of the slow-moving planets Saturn and Jupiter—as celestial harbingers of significant religious change or even the advent of the messianic era.9 Idel cites figures such as Moses ben Yehuda, Yehuda ben Nissim ibn Malka, and the influential historian and astronomer Abraham Zacuto as examples of thinkers who connected these Saturn-Jupiter conjunctions with eschatological expectations.9

However, the most profound positive reinterpretation of Saturn occurred within the development of theosophical Kabbalah. Idel meticulously traces the crucial conceptual move that linked Saturn to the third sefirah (divine emanation) in the Kabbalistic Tree of Life: Binah (Understanding or Intelligence).9 The sefirah of Binah itself held deep redemptive significance in Kabbalistic thought, often associated with the Jubilee year, liberation, the return to the divine source, and the womb of creation from which redemption emerges. Early Kabbalists, including Isaac the Blind (Sagi-Nahor), Joseph Gikatilla, and the authors of the Zohar, had already explored the connection between Binah and redemption.20 Yet, according to Idel, the explicit identification of Saturn with this redemptive sefirah was articulated later, primarily in the thirteenth century by the ecstatic Kabbalist Abraham Abulafia and the theosophical commentator Joseph ben Shalom Ashkenazi.14 By forging this link, these Kabbalists imbued Saturn—the planet of limitation and darkness—with the positive, expansive, and ultimately messianic qualities associated with Binah. This created a powerful symbolic triad: Saturn-Binah-Messiah.20

The dissemination of this potent symbolic complex was significantly aided by the anonymous late fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century Byzantine Kabbalistic work, Sefer ha-Peliy’ah (Book of Wonder), along with its companion text, Sefer ha-Kanah.1 Idel underscores the pivotal role of Sefer ha-Peliy’ah as a conduit for these ideas.20 This highly eclectic work, written in dialogue form and employing numerous parables, drew upon a vast range of sources, including the Zohar, prophetic Kabbalah (like Abulafia), the writings of Joseph Ashkenazi, Sefer ha-Temunah (another Byzantine work emphasizing cosmic cycles or shemittot), Ashkenazi Hasidic traditions, and late Midrashim.26 It placed a strong emphasis on Kabbalah as the key to understanding Judaism, criticized purely legalistic scholars, and featured recurring themes of messianism, eschatology, transmigration, and cosmic cycles, sometimes presenting views diverging from mainstream Spanish Kabbalah.26 Due to its (pseudepigraphically attributed) antiquity and its messianic calculations (predicting redemption around 1490, which resonated after the Spanish expulsion), Sefer ha-Peliy’ah gained considerable authority and influence, becoming canonized by the early sixteenth century and impacting figures from expelled Spanish Kabbalists to Joseph Karo, Moses Cordovero, and, crucially, Sabbatean figures.26

This constellation of ideas—Saturn linked with the redemptive sefirah of Binah, transmitted through influential texts like Sefer ha-Peliy’ah—converges, in Idel’s analysis, upon the figure of Sabbatai Tzevi, the seventeenth-century claimant to the messianic throne whose movement convulsed the Jewish world.5 Idel highlights several points of connection. Firstly, the name itself: Sabbatai (Hebrew: Shabbetai) is the Hebrew name for the planet Saturn, and was a common name for Jewish boys born on the Sabbath.9 Secondly, Sabbatean followers, as Idel demonstrates through sporadic references in Sabbatean documents, perceived Saturnian characteristics embodied in their leader.20 Thirdly, and most significantly, Idel argues that Sabbatai Tzevi’s own documented study of Sefer ha-Peliy’ah in his youth likely played a crucial role in shaping his messianic consciousness.9 This exposure, Idel suggests, allowed Tzevi to internalize the dual potential of Saturn: both the melancholic tendencies associated with the planet (resonating with his known manic-depressive or bipolar condition 20) and the profound redemptive power linked to the Saturn-Binah complex.9 This specific Saturnian conceptual structure, Idel proposes, may have served as a “conceptual trigger” contributing to Tzevi’s self-understanding as the Messiah and fueling the emergence of the Sabbatean movement.20

This interpretation offers a significant counterpoint or complement to the dominant explanation for Sabbateanism advanced by Gershom Scholem. Scholem famously attributed the movement’s rise primarily to the widespread diffusion of Lurianic Kabbalah, with its potent messianic and restorative doctrines, particularly in the aftermath of the collective trauma of the Spanish Expulsion.20 Scholem viewed Lurianism as the singular, indispensable background, an internal (“particularistic”) Jewish development driving the messianic fervor.20 While acknowledging Scholem’s monumental contribution and recognizing that Scholem was aware of the Saturn-Sabbatai name connection, Idel contends that Scholem did not fully appreciate the deeper significance of the Saturn-Binah-Messiah complex.20 Instead, Idel presents medieval astrology and the specific symbolism of Saturn, transmitted through texts like Sefer ha-Peliy’ah, as a crucial, perhaps complementary, “universalistic” cultural factor—an influence originating partly outside the specific framework of Lurianism—that incubated within Sabbateanism.20 Idel’s focus thus shifts from Scholem’s emphasis on broad historical currents and the impact of a specific mystical school (Lurianism) to the power of a particular, trans-culturally influenced symbolic configuration (Saturn-Binah-Messiah) in shaping the consciousness of the key individual, Sabbatai Tzevi, thereby offering a micro-historical, conceptual lens on a major historical phenomenon.

5. The Saturnine Temperament: Melancholy and the Jewish Intellectual

Beyond its associations with sorcery and messianism, Saturn carries another potent symbolic weight: its deep and enduring connection to the temperament of melancholy. Idel dedicates a chapter of Saturn’s Jews to exploring this nexus, tracing its historical roots and examining its perceived manifestation in modern Jewish intellectual life.14 The association between Saturn, the melancholic humor (black bile), and specific psychological traits, including a propensity for both profound despondency and intellectual depth, dates back to antiquity. The pseudo-Aristotelian Problemata (specifically Problem XXX, 1, discussed in the context of Klibansky et al. 29) famously explored why exceptional individuals in philosophy, politics, poetry, and the arts often appeared to be of a melancholic temperament. This linkage persisted and evolved through medieval medical, philosophical, and astrological thought.19

As established earlier, the astrological assignment of Saturn to the Jews led, from late antiquity onwards, to a connection being drawn between Jews and the psychological state of melancholy or despondency.18 Jews were sometimes characterized as inherently saturnine, prone to sadness and introspection due to their planetary ruler.

Idel’s analysis heavily engages with the landmark study Saturn and Melancholy by Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl, a cornerstone of the Warburg school’s legacy.14 This work meticulously documented the complex history of the melancholy concept, emphasizing Saturn’s paradoxical nature: the planet believed to confer not only dejection, slowness, and misery, but also, particularly from the Renaissance onwards (influenced by thinkers like Marsilio Ficino 29), intellectual profundity, contemplative genius, and creative power.18 Melancholy, in this revised view, could be the mark of the inspired thinker or artist.

Idel extends this complex understanding of the Saturnine temperament into the twentieth century, examining its perceived relevance for understanding certain modern Jewish intellectuals.1 He focuses particularly on figures associated with Gershom Scholem, himself a pivotal figure in twentieth-century Jewish thought.9 Idel discusses the “Saturnine temperament” and disposition towards melancholy observed in individuals like Walter Benjamin (whose work explicitly engaged with the Saturn-melancholy theme, drawing on Panofsky and Saxl 18), the Nobel laureate S.Y. Agnon, and the writer Werner Kraft.9 This resonates with Scholem’s own poetic observation regarding a tendency towards melancholy within interbellum German Jewry.9

However, Idel approaches this connection with characteristic nuance. He notes that while these modern Jewish intellectuals were undoubtedly aware of, and in some cases deeply experienced, melancholy, their understanding of it was often disconnected from the earlier, explicitly astrological framework linking melancholy directly to the planet Saturn.9 The association persisted culturally or psychologically, but often detached from its astrological origins.

Furthermore, Idel carefully navigates the sensitive question of whether melancholy constitutes an inherent trait of the Jewish people due to their supposed governance by Saturn.9 He explores the historical persistence of this idea but ultimately distances himself from any deterministic interpretation based on astral causality. In a powerful personal testimony included in the book, Idel—whose own planetary ruler, he notes, happens to be Saturn—explicitly rejects such essentializing beliefs.9 His analysis thus avoids reinforcing stereotypes about the “melancholic Jew.” Instead, it uses the historical Saturn-melancholy complex as a lens through which to examine aspects of modern Jewish intellectual experience, recognizing the potential link between introspection, suffering (perhaps amplified by historical experience 18), and intellectual or spiritual depth, without resorting to astrological determinism. This section demonstrates Idel’s engagement with the Warburg tradition not merely as a source of methodological tools but also as a framework for thematic analysis applied to modern Jewish culture. It reveals his critical stance towards essentialist interpretations of Jewish identity while simultaneously acknowledging the enduring power of historical symbols and psychological archetypes like the Saturnine melancholic in shaping intellectual discourse and self-perception.

6. Sources and Foundations: Texts and Thinkers in “Saturn’s Jews”

Moshe Idel’s scholarship is characterized by its profound immersion in primary source materials, often drawing upon extensive work with manuscripts collected over decades.5 Saturn’s Jews is no exception; its arguments are meticulously constructed upon close readings and interpretations of a diverse range of Jewish texts spanning from antiquity to the early modern period. Understanding the specific sources Idel engages with is crucial for appreciating the foundations of his thesis regarding Saturnism.

Idel’s analysis draws upon the foundational layers of Jewish tradition. Talmudic sources provide early evidence for the association between Saturn and the Sabbath, most notably the passage in tractate Shabbat 156a identifying Saturn as Shabbetai.16 While not explicitly focused on Saturn, the broader context of Rabbinic literature (Mishnah, Talmud) forms the backdrop against which later mystical and philosophical ideas developed.25 Midrashic literature, with its homiletical and allegorical interpretations, also serves as a resource for tracing the development of certain motifs and interpretive approaches relevant to Idel’s themes.26

The core of Idel’s textual analysis, however, lies within the rich and complex corpus of Kabbalistic literature. The Zohar, the foundational work of theosophical Kabbalah attributed to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai but largely composed by Moses de León in thirteenth-century Spain 39, is a key reference point. Its discussions of the sefirot, particularly the redemptive qualities associated with Binah, provide the essential groundwork for the later Kabbalistic revaluation of Saturn.20 Commentaries on the ancient cosmological text Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Formation) are also vital, especially the commentary attributed to Rabbi Joseph ben Shalom Ashkenazi. Idel highlights passages from this work (preserved in manuscript and quoted extensively in Sefer ha-Peliy’ah) as crucial evidence for the explicit linking of Saturn with the sefirah of Binah and concepts of redemption.5

Perhaps the most pivotal texts for Idel’s argument concerning the positive, messianic interpretation of Saturn are the anonymous Byzantine works, Sefer ha-Peliy’ah (Book of Wonder) and its companion Sefer ha-Kanah (Book of the Reed Pen), likely composed in the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century.26 Idel demonstrates how these highly influential, albeit eclectic, works served as crucial vehicles for transmitting the Saturn-Binah-Messiah conceptual complex, incorporating ideas from Abulafia, Ashkenazi, the Zohar, and Sefer ha-Temunah.1 Their emphasis on messianism and their later canonization made them particularly significant for figures involved in the Sabbatean movement.26

Beyond these major works, Idel analyzes the writings of numerous specific thinkers who engaged with the symbolism of Saturn across different periods:

- Abraham Ibn Ezra (ca. 1089–ca. 1161): The influential Spanish biblical commentator, poet, and philosopher was the first major Jewish thinker to systematically address the problematic astrological link between Saturn, the Sabbath, and the Jews. He notably reinterpreted Saturn’s influence positively, suggesting Sabbath observance could mitigate its negative aspects and enhance religious devotion.5

- Abraham Abulafia (1240–c. 1291): A central figure in ecstatic Kabbalah, Abulafia developed techniques for achieving mystical experiences through the manipulation of Hebrew letters and divine names.42 Idel identifies him as a key figure in associating Saturn positively with the sefirah of Binah and linking this complex to messianic redemption, albeit understood in spiritual, experiential terms.1

- Joseph ben Shalom Ashkenazi (c. 13th-14th c.): A theosophical Kabbalist whose commentary on Sefer Yetzirah provided explicit textual support, heavily utilized by Idel, for the connection between Saturn, Binah, and redemption, passages of which were incorporated into Sefer ha-Peliy’ah.5

- Shlomo Franco / Shem Tov ibn Major (14th c.): Jewish thinkers cited by Idel primarily for their discussions illustrating the negative, demonic, or sorcerous aspects attributed to Saturn within certain Jewish circles.9

- Yohanan Alemanno (late 15th c.): An Italian Jewish Renaissance figure whose syncretic thought incorporated Kabbalah, philosophy, and magic. Idel references his work as reflecting the continued presence of Saturn’s negative astrological associations.9

- Abraham Zacuto (c. 1452–c. 1515): Spanish-Portuguese astronomer, historian, and rabbi, noted by Idel for linking Saturn-Jupiter conjunctions to messianic predictions.9

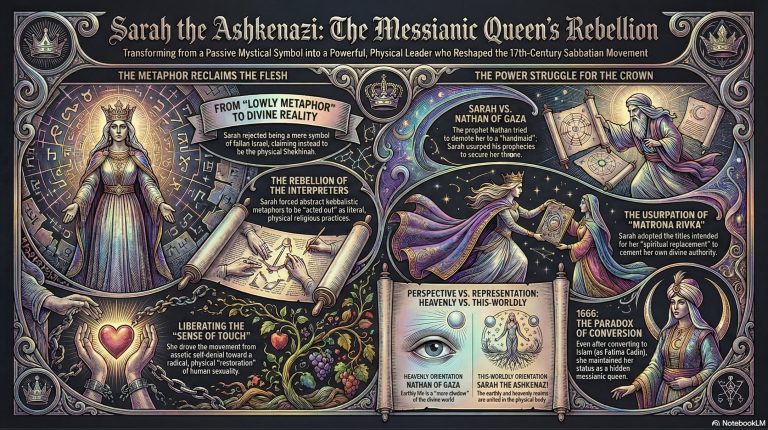

- Sabbatai Tzevi (1626–1676): The central figure of the Sabbatean movement, whose life, name, and self-perception Idel analyzes through the lens of the Saturn-Binah-Messiah complex, particularly as influenced by Sefer ha-Peliy’ah.5

- Nathan of Gaza (1643–1680) / Moshe Hayyim Luzzatto (1707–1746): Sabbatai Tzevi’s prophet and a later prominent Italian Kabbalist, respectively, whose writings contain references or interpretations related to the Saturn-Sabbatai Tzevi connection, discussed by Idel in the later reverberations of Sabbateanism.14

To clarify the complex web of associations Idel traces, the following table summarizes the key texts and thinkers discussed in Saturn’s Jews and their primary connection to the symbolism of Saturn:

| Text / Thinker | Period | Key Association with Saturn (Negative/Positive) | Concept Linked | Idel’s Argument / Significance | Key Snippet Refs |

| Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 156a) | Talmudic (c. 500 CE) | Neutral/Factual | Sabbath | Establishes basic Saturn (Shabbetai) = Star of Sabbath link within Jewish tradition. | 16 |

| Al-Kabi’si (Alcabitius) | 10th c. CE | Negative (Implied) | Jews, Sabbath, Sorcery | Possible earliest attestation of the negative Saturn-Jew-Sabbath-Sorcery nexus (via Arab astrology). | 9 |

| Abraham Ibn Ezra | 11th-12th c. | Primarily Positive (Reinterpreted) | Sabbath, Jews, Faith | First major Jewish engagement; reinterprets Saturn’s influence as potentially beneficial for faith via Sabbath observance. | 5 |

| Abraham Abulafia | 13th c. | Positive | Binah, Messianism (Spiritual), Sorcery (Ambivalent) | Links Saturn to Binah and spiritual redemption; complex views on magic/sorcery also noted. | 5 |

| Joseph ben Shalom Ashkenazi | 13th-14th c. | Positive | Binah, Redemption, Sabbath | Commentary on Sefer Yetzirah explicitly links Saturn-Binah-Redemption; passages crucial for Sefer ha-Peliy’ah. | 5 |

| Zohar | Late 13th c. | (Context) | Binah, Redemption | Provides foundational concept of Binah‘s redemptive role, later linked to Saturn. | 20 |

| Shlomo Franco / Shem Tov ibn Major | 14th c. | Negative | Demons, Sorcery, Goats | Exemplify explicit articulation of Saturn’s demonic/negative aspects in Jewish sources. | 9 |

| Sefer ha-Peliy’ah / Sefer ha-Kanah | Late 14th-Early 15th c. | Primarily Positive (Messianic) | Binah, Messianism, Redemption, Cosmic Cycles (Shemittot) | Central text transmitting Saturn-Binah-Messiah complex; highly influential, esp. on Sabbateanism. | 1 |

| Yohanan Alemanno | Late 15th c. | Negative | Astrology, Sorcery | Italian Renaissance figure whose work reflects continued awareness of Saturn’s negative astrological profile. | 9 |

| Abraham Zacuto | 15th-16th c. | Positive (Astrological) | Messianism, Planetary Conjunctions | Linked Saturn-Jupiter conjunctions to messianic expectations. | 9 |

| Sabbatai Tzevi | 17th c. | Both (Internalized) | Messiah, Melancholy, Redemption | Central figure influenced by Peliy’ah; embodied Saturn’s duality (melancholy/redemption); name means Saturn. | 5 |

| Nathan of Gaza / M. H. Luzzatto | 17th-18th c. | (Interpretive) | Sabbatai Tzevi, Redemption | Later figures interpreting or referencing the Saturn-Sabbatai Tzevi link. | 14 |

This table provides a structured overview of the textual and intellectual landscape Idel navigates in Saturn’s Jews, demonstrating how the multifaceted symbolism of Saturn was engaged, contested, and transformed within Jewish thought over centuries.

7. Scholarly Dialogue: Critiques and Alternative Perspectives

Moshe Idel’s Saturn’s Jews has been recognized by scholars as a significant and stimulating contribution to the study of Jewish mysticism and intellectual history. Reviewers often praise the book’s thorough research, eloquent writing, and Idel’s characteristic deep engagement with often obscure primary sources, including manuscript materials.5 The work is seen as offering novel interpretations of aspects of Judaism, particularly concerning the interplay of astrology and Kabbalah, and shedding new light on the complex background of phenomena like Sabbateanism.4

However, alongside this appreciation, certain aspects of Idel’s thesis have drawn scholarly critique and invited alternative perspectives. The most frequently questioned element is the proposed link between the negative Saturn-Sabbath-sorcery complex in Jewish thought and the emergence of the European myth of the Witches’ Sabbat.9 While reviewers acknowledge the originality and potential interest of this hypothesis, they generally find the direct evidence presented by Idel to be suggestive rather than conclusive.9 Critics point out that the specific rituals and beliefs associated with the Witches’ Sabbat are often more readily traceable to indigenous European folklore, Christian demonology, and pre-existing anti-Jewish stereotypes than to the specific Saturnine concepts found in the relatively limited circulation of late medieval Jewish elite texts.9 The argument, therefore, while provocative, remains largely speculative in the eyes of many specialists in witchcraft studies and medieval history.

Some reviewers have also commented on the book’s methodological scope. While appreciating Idel’s focus on the history of concepts and the transmission of symbolic structures, one review noted that this approach might appear somewhat “restricted to a notional framework” when compared to broader socio-historical narratives.20 This is less a critique of the validity of Idel’s findings and more an observation about the specific nature of his contribution as primarily belonging to the history of ideas, focusing intensely on the internal logic and evolution of specific conceptual clusters related to Saturn.20

Inevitably, any major work on Jewish mysticism, particularly one dealing with Sabbateanism, invites comparison with the foundational scholarship of Gershom Scholem.20 Saturn’s Jews engages, both explicitly and implicitly, in a significant dialogue with Scholem’s legacy. The most prominent point of contrast lies in their respective explanations for the rise of Sabbateanism. As discussed earlier, Scholem’s magisterial work emphasized the dissemination of Lurianic Kabbalah and the historical trauma of the Spanish Expulsion as the primary, largely internal Jewish (“particularistic”) factors driving the movement.20 Idel, conversely, highlights the role of the Saturn-Binah-Messiah complex, rooted in part in the “universalistic” discourse of medieval astrology and transmitted through texts like Sefer ha-Peliy’ah, as a significant contributing element.9 He suggests that Scholem, despite his vast erudition, did not fully integrate the significance of this Saturnine dimension into his analysis.20

This difference in explaining Sabbateanism reflects broader divergences in historiographical approach. Scholem, particularly in his work on Sabbateanism, tended towards constructing grand narratives often centered on a single major causal factor (like Lurianism) emerging from within Jewish history.20 Idel’s approach, here and elsewhere in his work, often emphasizes multiplicity, cultural exchange, and the impact of external intellectual currents (like astrology, Neoplatonism, or magic) on Jewish thought.5 He frequently seeks to reintegrate aspects of Jewish experience, such as magic and astrology, that might have been relatively marginalized in Scholem’s later focus on theosophical and mystical developments, arguing for a more porous boundary between internal Jewish traditions and the broader cultural environment.3 Reading Saturn’s Jews thus requires understanding its position within this ongoing scholarly conversation. It represents an effort to provide alternative or complementary frameworks for understanding key developments in Jewish mystical history by foregrounding intellectual currents and symbolic configurations that Scholem’s influential narrative may have underplayed.

8. Synthesis and Conclusion

Moshe Idel’s Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism weaves together a complex and fascinating tapestry of historical, mystical, astrological, and psychological threads. The book meticulously excavates the long and ambivalent history of “Saturnism”—the association of the planet Saturn with Jewish identity and destiny.5 Idel demonstrates how this association, rooted in the alignment of the seventh planet with the seventh day (Sabbath), generated a dualistic legacy within Jewish thought. On one hand, Saturn’s traditional astrological malignancy fostered negative connections linking Jews to misfortune, sorcery, and, Idel speculatively proposes, even contributing conceptually to the myth of the Witches’ Sabbat.5 On the other hand, through specific Kabbalistic interpretations—most notably the linkage of Saturn with the redemptive sefirah of Binah transmitted via texts like Sefer ha-Peliy’ah—the planet acquired a positive valence connected to hope, messianism, and divine understanding.5 This positive structure, Idel argues, played a crucial role in the self-perception of Sabbatai Tzevi and the emergence of the Sabbatean movement.5 Furthermore, Idel extends the reach of Saturn’s influence by exploring the enduring association between the planet, the temperament of melancholy, and the perceived disposition of Jewish intellectuals, particularly in the modern era, while carefully avoiding deterministic conclusions.9

The primary contribution of Saturn’s Jews lies in its recovery and systematic analysis of this largely neglected strand of Jewish intellectual history. Idel compellingly demonstrates that astrology, far from being merely a marginal or external curiosity, functioned as a significant conduit for ideas and symbolic frameworks that interacted dynamically with internal Jewish traditions like Kabbalah.5 His work exemplifies the complex interplay between what he terms “universalistic” influences (astrology, philosophy, ancient mythologoumena shared across cultures) and “particularistic” elements (Jewish textual interpretation, Kabbalistic theosophy, halakhic observance) in the shaping of Jewish thought and identity.20 By foregrounding the role of Saturnine symbolism, Idel broadens the scope of inquiry into Jewish intellectual history, challenging narratives that might overemphasize internal developments or downplay the impact of seemingly esoteric or non-rabbinic fields like astrology and magic. His analysis of the Saturn-Binah-Messiah complex as a factor in Sabbateanism offers a valuable conceptual counterpoint to Scholem’s dominant Lurianic explanation, enriching the understanding of that pivotal historical moment.

The enduring significance of Saturn’s Jews extends beyond its specific historical findings. Methodologically, it showcases Idel’s approach of meticulously tracing conceptual structures and symbolic clusters across diverse texts and periods, revealing hidden continuities and transformations. The book implicitly challenges monolithic or overly simplistic definitions of Judaism, revealing a tradition capable of absorbing, reinterpreting, and grappling with complex and even contradictory symbols drawn from both internal and external sources.5 It demonstrates the dynamic, unpredictable, and often surprising ways in which ideas are transmitted and contested across cultural and historical boundaries, highlighting how astrological concepts could influence everything from messianic fervor to perceptions of collective temperament. Idel’s work underscores the necessity of examining the “shadow” aspects, the complex symbolisms, and the cross-cultural dialogues within religious traditions to achieve a more complete and nuanced understanding of their historical development. His implicit call for more interdisciplinary approaches, bridging the study of religion, intellectual history, art history (following the Warburgian model), and psychology, remains a valuable directive for future research into the intricate layers of Jewish thought and experience.9 Saturn’s Jews ultimately illuminates the profound ways in which the celestial and the terrestrial, the ancient and the modern, the mystical and the historical, converged under the complex sign of Saturn.

Works cited

- Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat… book by Moshe Idel – ThriftBooks, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.thriftbooks.com/w/saturns-jews-on-the-witches-sabbat-and-sabbateanism_moshe-idel/13922516/

- By Moshe Idel – Kabbalah: New Perspectives – Amazon.com, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Moshe-Idel-Kabbalah-New-Perspectives/dp/B008UYWM72

- Moshe Idel – Wikipedia, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moshe_Idel

- Saturn’s Jews – (robert And Arlene Kogod Library Of Judaic Studies) By Moshe Idel (paperback) – Target, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.target.com/p/saturn-s-jews-robert-and-arlene-kogod-library-of-judaic-studies-by-moshe-idel-paperback/-/A-94192198

- Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism 9781472548672, 9781441121448, 9780826444530 – DOKUMEN.PUB, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://dokumen.pub/saturns-jews-on-the-witches-sabbat-and-sabbateanism-9781472548672-9781441121448-9780826444530.html

- Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism: The Robert and Arlene Kogod Library of Judaic Studies Moshe Idel Continuum – Bloomsbury Publishing, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/saturns-jews-9781441121448/

- The Jew and human sacrifice; human blood and Jewish ritual, an, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/sacrifice-Jewish-historical-sociological-inquiry/dp/B00AW4NA60

- REVIEWS – Association of Jewish Libraries, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://jewishlibraries.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/reviews2012_09_10.pdf

- Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism – Liverpool University Press, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/doi/pdf/10.18647/3253/JJS-2015?download=true

- Saturn’s Jews, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.hartman.org.il/saturns-jews/

- [PDF] Saturn’s Jews by Moshe Idel | 9780826444530, 9781441137319 – Perlego, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.perlego.com/book/805810/saturns-jews-on-the-witches-sabbat-and-sabbateanism-pdf

- Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism: 10 – Idel, Moshe – Amazon, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.amazon.com.au/Saturns-Jews-Witches-Sabbat-Sabbateanism/dp/0826444539

- Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism (The Robert and Arlene Kogod Library of Judaic Studies): Idel, Moshe: 9781441121448 – Amazon.com, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Saturns-Jews-Witches-Sabbateanism-Library/dp/1441121447

- Saturn’s Jews, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9781441137319_A23998767/preview-9781441137319_A23998767.pdf

- Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism by Moshe Idel, Paperback, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/saturns-jews-moshe-idel/1129818459

- Saturn and the Jews | Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://katz.sas.upenn.edu/resources/blog/saturn-and-jews

- Angels and Mazalot – Chabad.org, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/361901/jewish/Angels-and-Mazalot.htm

- Melancholic Redemption and the Hopelessness of Hope – PhilArchive, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://philarchive.org/archive/WOLMRA

- Saturn and Melancholy | McGill-Queen’s University Press, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.mqup.ca/saturn-and-melancholy-products-9780773559493.php

- Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism. By …, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-journal-of-asian-studies/article/saturns-jews-on-the-witches-sabbat-and-sabbateanism-by-moshe-idel-kogod-library-of-judaic-studies-vol-10-london-bloomsbury-publishing-2011-pp-216-isbn-10-1441121447-13-9781441121448/EC6444457BF7D473C614ACE5F8E0D8EF

- Chapter 2 The Imagery of Cosmic and Human Orders in – Brill, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004499003/BP000010.xml

- Sabbatai Zevi – Wikipedia, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sabbatai_Zevi

- Io, Saturnalia! – Saturn , Shabbathai אגיאל | Ars Magine, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://arsmagine.com/others/saturn/

- saturn and sabbatai tzevi: – a new approach to sabbateanism, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.zefat.ac.il/media/3541/saturn_and_sabbatai_tzevi_-_a_new_appro.pdf

- Kabbalah: An Overview – Jewish Virtual Library, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/kabbalah-an-overview

- Kanah and Peliyah, Books of – Jewish Virtual Library, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/kanah-and-peliyah-books-of

- Chapter 3 Coveted Kabbalah: Widmanstetter’s Collaboration with Jewish and Convert Scribes in – Brill, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004689527/BP000003.xml

- Sabbatai Zevi and the Sabbatean Movement (Chapter 18) – The Cambridge History of Judaism, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-history-of-judaism/sabbatai-zevi-and-the-sabbatean-movement/10D5A1FB8D131C58B6F9792E824E7EA1

- Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art [New ed.] 0773559493, 9780773559493 – DOKUMEN.PUB, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://dokumen.pub/saturn-and-melancholy-studies-in-the-history-of-natural-philosophy-religion-and-art-newnbsped-0773559493-9780773559493.html

- Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art – Amazon.com, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Saturn-Melancholy-Studies-Philosophy-Religion/dp/0773559493

- Saturn and Melancholy : Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art – Amazon.com, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Saturn-Melancholy-Studies-Philosophy-Religion/dp/B0000CM9SC

- Saturn And Melancholy Studies In The History Of Natural Philosophy, Religion And Art : Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky & Fritz Saxl : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming – Internet Archive, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://archive.org/details/saturn-and-melancholy-studies-in-the-history-of-natural-philosophy-religion-and-art

- Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/18005837-saturn-and-melancholy

- Swiss Jewish Thinker Jean Starobinski Isn’t Slowing Down Even at 92 – The Forward, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://forward.com/culture/172386/swiss-jewish-thinker-jean-starobinski-isnt-slowing/

- Yearnings of the Soul, accessed on April 15, 2025, http://students.aiu.edu/submissions/profiles/resources/onlineBook/i7S9Q6_Soul_Psychological_Kabbalah.pdf

- Moshe Idel: Representing God – dokumen.pub, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://dokumen.pub/download/moshe-idel-representing-god-1nbsped-9789004280786-9789004280779.html

- On Neglected Hebrew Versions of Myths of the Two Fallen Angels – Philosophy and the Mind Sciences, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://philosophymindscience.org/index.php/ER/article/download/9518/9152

- Coveted Kabbalah: Widmanstetter’s Collaboration with Jewish and Convert Scribes – Brill, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://brill.com/downloadpdf/display/book/9789004689527/BP000003.pdf

- Sefer ha-zohar | Kabbalah, Mysticism, Commentary – Britannica, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sefer-ha-zohar

- “תומיאתמ ןניאש תוימואת תולעמ” “Improper Twins”: The Ambivalent “Other Side” in the Zohar and Kabbalistic Tradition – UCL Discovery, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1435419/1/Berman%20-%20Improper%20Twins%20-%20The%20Ambivalent%20Other%20Side%20in%20the%20Zohar.pdf

- Visualization of Colors, 1: David ben Yehudah he-Ḥasid’s Kabbalistic Diagram | Ars Judaica, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/journals/article/62142/

- Moshe Idel — Kabbalistic Manuscripts in the Vatican Library – The Seforim Blog, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://seforimblog.com/2010/01/moshe-idel-kabbalah-manuscripts-in/?print=print

- Visual Kabbalah | PDF – Scribd, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://it.scribd.com/document/715136474/Visual-Kabbalah

- Full text of “Moshe Idel: Studies in Kabbalah” – Internet Archive, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://archive.org/stream/MosheIdel/MosheIdel-MessianicMystics_djvu.txt

- Witches, Jews, and Redemption Through Sin in Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière – Columbia Academic Commons, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/d8-e0w3-mg16/download

- Messianic Mystics 9780300145533 – DOKUMEN.PUB, accessed on April 15, 2025, https://dokumen.pub/messianic-mystics-9780300145533.html

Summary

This document provides a detailed analysis of Moshe Idel’s book “Saturn’s Jews: On the Witches’ Sabbat and Sabbateanism,” which explores the historical and symbolic connections between the planet Saturn and Jewish identity, mysticism, and history.

Idel argues for the concept of “Saturnism,” where Saturn has a persistent association with the Jewish people due to astrological assignments. He employs a Warburgian methodological framework, focusing on the dualistic symbolism of Saturn, encompassing both negative connotations like misfortune and sorcery, and positive ones such as redemption and messianism.

The document delves into Saturn’s negative aspects, including links to sorcery and a proposed connection to the myth of the Witches’ Sabbat. It also examines the positive interpretations, where Saturn is associated with the Kabbalistic sefirah of Binah, redemption, and messianic figures like Sabbatai Tzevi.

Furthermore, the document discusses the Saturnine temperament and its connection to melancholy in Jewish intellectual life. It outlines the key textual sources and thinkers Idel references, including Talmudic texts, Kabbalistic works like the Zohar and Sefer ha-Peliy’ah, and figures like Abraham Abulafia and Abraham Ibn Ezra.

The report also addresses scholarly critiques of Idel’s work, particularly concerning the Witches’ Sabbat hypothesis and the comparisons to Gershom Scholem’s views on Sabbateanism. It concludes by highlighting Idel’s contribution to understanding the interplay between astrology, Kabbalah, and Jewish identity, emphasizing his interdisciplinary approach and the complexity of historical and symbolic influences.

An Astronomical Addenda

Recent discoveries have added curious footnotes-

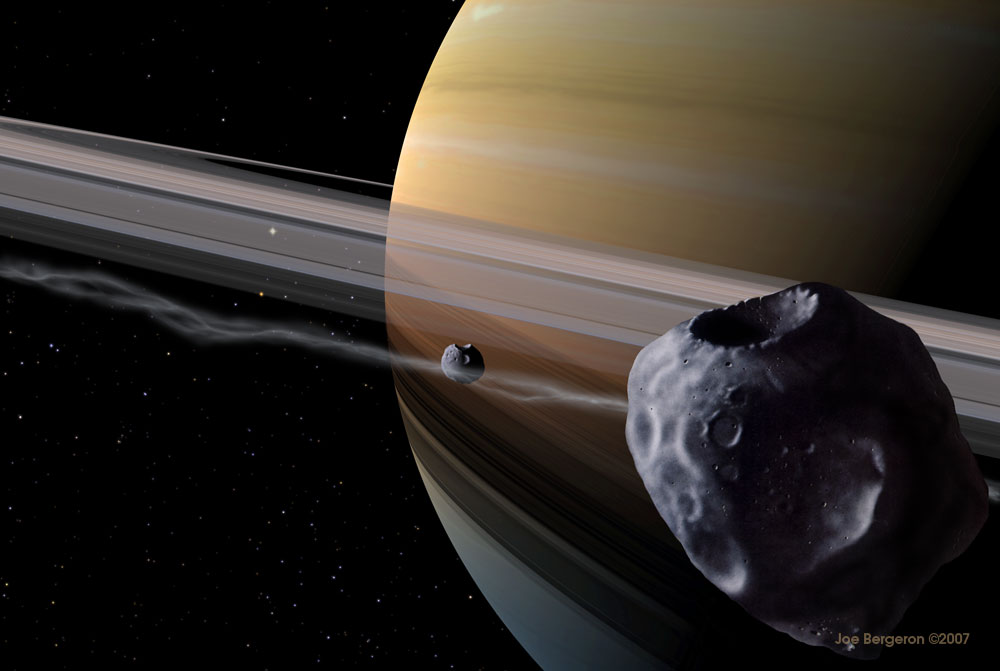

1. The Shepherd Moons of Saturn’s Rings & the Gentiles

The relationship between Saturn’s shepherd moons and its rings, and the function of Gentiles in relation to the Jewish people, can be explored as a compelling set of cognates. A cognate is a concept or entity that is similar in nature or function to another, and this analogy provides a framework for understanding complex relationships through a scientific and theological lens.

Saturn’s rings are not static, uniform bands of material. They are intricate systems of ringlets and gaps, and they are kept in their defined structure by the gravitational influence of small moons called shepherd moons. The term “shepherd” is an apt metaphor, as these moons act like shepherds guiding a flock.3

- Containment and Definition: Shepherd moons, such as Pan and Prometheus, orbit near the edges of a ring or within gaps.4 Through their gravitational pull, they “herd” the ring particles, preventing them from spreading out and dissipating. This gravitational interaction keeps the rings confined to narrow, well-defined paths. For example, Pan maintains the Encke Gap in the A ring, while Prometheus and Pandora are associated with the F ring, preventing it from dispersing.

- Creating and Maintaining Structure: The gravitational tugs from these moons also create waves and ripples within the rings, contributing to their complex and dynamic structure. Without the shepherd moons, the rings would likely spread out over time and eventually disappear. The moons are not a part of the ring itself, but they are essential for the ring’s existence and form.

The Theological Function of the Gentiles

In a theological context, particularly within Christianity, the relationship between Gentiles and the Jewish people is described in a way that resonates with the shepherd moon analogy. The Jewish people, as the “chosen people,” are seen as having a special covenant with God. The role of the Gentiles (non-Jews) is not to replace the Jewish people, but to have a distinct, yet interconnected, function.

- A “Wild Olive Branch”: The Apostle Paul in the book of Romans uses the metaphor of an olive tree to describe this relationship. He likens Israel to the natural branches of the tree, and the Gentiles to “wild olive branches” that have been “grafted in” (Romans 11:17). This image suggests that Gentiles partake in the “richness of the olive tree,” which represents the covenants, promises, and blessings given to Israel.

- Spurring “Jealousy” and Restoration: Paul suggests that the inclusion of the Gentiles is intended to make the Jewish people “envious,” thereby leading to their own restoration and “full inclusion” (Romans 11:11-12). In this sense, the Gentiles, by coming to faith, are a force that helps to define and ultimately lead to the fulfillment of Israel’s own destiny. They are not the root of the tree, but their presence is a catalyst for the health and vitality of the entire plant.

- Mutual Dependence: The relationship is one of mutual dependence. The Gentiles cannot have the blessings of the covenant without the Jewish root, and the Jewish people’s ultimate purpose is linked to the salvation of the world, which includes the Gentiles. This dynamic interaction prevents the Jewish people from becoming isolated and ensures the fulfillment of the divine plan.

A Cognate Analogy

The shepherd moon and Gentile functions serve as a powerful cognate:

| Feature | Shepherd Moons | Gentiles |

| Object of Influence | Saturn’s rings | The Jewish people (Israel) |

| Function | To confine, define, and maintain the structure of the rings. | To be “grafted in” and, by their inclusion, to spur the restoration and fulfillment of Israel’s purpose. |

| Relationship | The moons are distinct from the rings but their gravitational influence is essential for the rings’ existence. | The Gentiles are distinct from the Jewish people but their theological function is essential for the fulfillment of the divine plan for Israel and the world. |

| Outcome | Prevents the rings from spreading out and dissipating. | Prevents Israel from being isolated and helps to bring about the ultimate plan of salvation for all nations. |

In both cases, an external, gravitationally or theologically “tugging” force is crucial for the existence, definition, and ultimate destiny of a central entity. The shepherd moons don’t become the rings, and the Gentiles do not replace the Jewish people. Instead, they are cognate functions that work in tandem to create and maintain a complex, dynamic, and ultimately purposeful system.

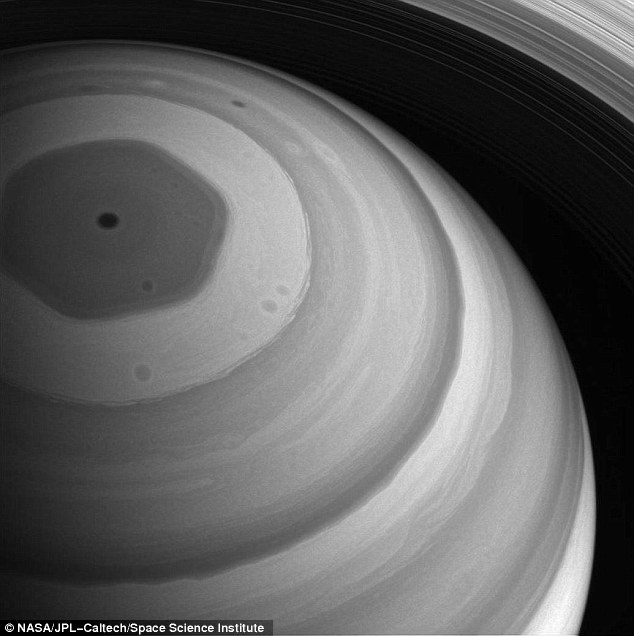

2. The Hexagon structure at Saturns North Pole

The exploration of a cognate relationship between the hexagon at Saturn’s north pole and the Jewish people is a fascinating exercise in connecting celestial phenomena with theological and cultural symbolism. This approach, similar to the previous one with the shepherd moons, seeks to find meaningful parallels not in a literal or scientific sense, but in a conceptual and symbolic one.

Saturn’s Hexagon: A Scientific Perspective

The hexagon at Saturn’s north pole is a massive, enduring, and mysterious atmospheric feature. Discovered by the Voyager mission in the 1980s and studied in detail by the Cassini spacecraft, it is a jet stream with a distinct six-sided shape.

- A stable, contained form: The hexagon is not a random occurrence. It is a stable, geometric structure formed by atmospheric winds and a powerful polar vortex. Its shape is believed to be the result of a standing wave in the atmosphere, and while scientists have been able to replicate similar shapes in lab experiments, the specific conditions on Saturn that create and maintain this perfect hexagon are still a subject of research.

- A “boundary” of the pole: The hexagon defines and contains the region around the north pole. It’s a clear boundary, a distinct shape that sets apart a specific area of the planet.

- A point of focus and stability: The hexagon rotates with Saturn’s interior, unlike other weather patterns that shift. This makes it a fixed, stable point of reference.

The Jewish People and the Symbolism of Six

In Jewish thought, the number six and the hexagon (or hexagram) carry a deep and multifaceted significance.

- The Six Days of Creation: The most fundamental association is with the six days of creation, as recounted in the book of Genesis. The six days of work culminating in the seventh day of rest (Shabbat) represent the physical, created world and its connection to the divine. This links the number six to the material world, human labor, and the process of bringing order out of chaos.

- The Magen David (Star of David): The Star of David, a hexagram composed of two overlapping triangles, is the most recognizable symbol of Judaism. While its usage as a widespread Jewish symbol is relatively recent (dating to the Middle Ages), its symbolism is often rooted in Kabbalah, Jewish mysticism. The two triangles are seen as representing the relationship between God and humanity: one pointing up to the heavens, the other pointing down to the earth. This signifies the reciprocal connection between the divine and the material world, and the Jewish people’s role as a bridge between the two. The central hexagon within the star is often seen as a symbol of the heart, the core of this relationship.

- Completeness and Wholeness: In Kabbalistic tradition, the number six is associated with the six cardinal directions (north, south, east, west, up, down), representing the encompassing presence of God in all of creation. It can also signify completion and harmony, as a perfect number (one where the sum of its divisors equals the number itself, 1+2+3=6).

The Cognate: An Analogical Connection

Drawing a cognate between Saturn’s hexagon and the Jewish people highlights several powerful themes:

- A Stable and Enduring Identity: Just as the hexagon is a stable, enduring, and well-defined atmospheric feature on Saturn, the Jewish people are a distinct group with a history that has persisted through millennia. The hexagon’s unshifting nature, rotating in sync with the planet’s interior, can be seen as a parallel to the Jewish people’s enduring identity and their continuous adherence to the covenant (the “interior” of their faith), even amidst the changing “weather patterns” of the world.

- A Boundary and a Center: The hexagon defines a specific, contained region on Saturn’s pole, setting it apart from the rest of the planet’s atmosphere. In a similar vein, the Jewish people, through their unique covenant and traditions, have historically been set apart from the nations. This “boundary” is not about exclusion but about maintaining a distinct identity and purpose. The central vortex within the hexagon can be seen as a cognate for the spiritual “heart” of the Jewish people—the core of their faith and their connection to God.

- A Symbol of Creation and Order: The hexagon’s geometric perfection and its association with a standing wave in the atmosphere resonate with the Jewish symbolism of the number six and the six days of creation. Both represent an ordered and purposeful design within the cosmos. The hexagon is a physical manifestation of order in a turbulent gaseous environment, just as the six days of creation represent God’s ordering of the physical world. The Star of David, with its central hexagon, similarly embodies the balance and harmony between the divine and the earthly.

In this cognate, Saturn’s hexagon serves as a powerful natural metaphor for the Jewish people’s enduring, distinct, and divinely ordered identity. It is a symbol of a stable core, a defined boundary, and a profound connection between the terrestrial and the celestial, reflecting the unique and central role of the Jewish people in the grand narrative of creation and covenant.

3. Saturn’s Brightness and Conjunctions

- The “Star of Bethlehem”: One of the most famous examples of planetary alignment having religious significance is the so-called “Star of Bethlehem.” While a star is mentioned in the New Testament, some scholars and astronomers have proposed that the event was a rare conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn. Johannes Kepler, a 17th-century astronomer, calculated a triple conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in the constellation of Pisces in 7 BCE. This constellation, Pisces, was known in ancient astrology as “the house of the Hebrews.” To astrologers like the Magi, a rare triple conjunction of Jupiter (a royal symbol) and Saturn (seen as Israel’s protector) in the “house of the Hebrews” would have been a significant sign of the birth of a Jewish king. This astronomical event, though debated, highlights how the movements of these planets were seen as portents for Jewish-related events.

- Messianic Hope and Planetary Conjunctions: In medieval Jewish thought, particularly in the works of figures like Abraham Ibn Ezra, the movements of Saturn and Jupiter were sometimes associated with messianic expectations. The “great conjunctions” of these two planets were seen by some as heralding major historical shifts and changes in religion, with some even linking them to the dawning of the messianic era. This idea shows a sophisticated engagement with astrology as a tool for interpreting the cosmic plan, even as mainstream Judaism rejected idolatry and astral worship.//