Introduction

An Audio Deep Dive by Google NotebookLM

An Audio Debate on the Subject by Google NotebookLM

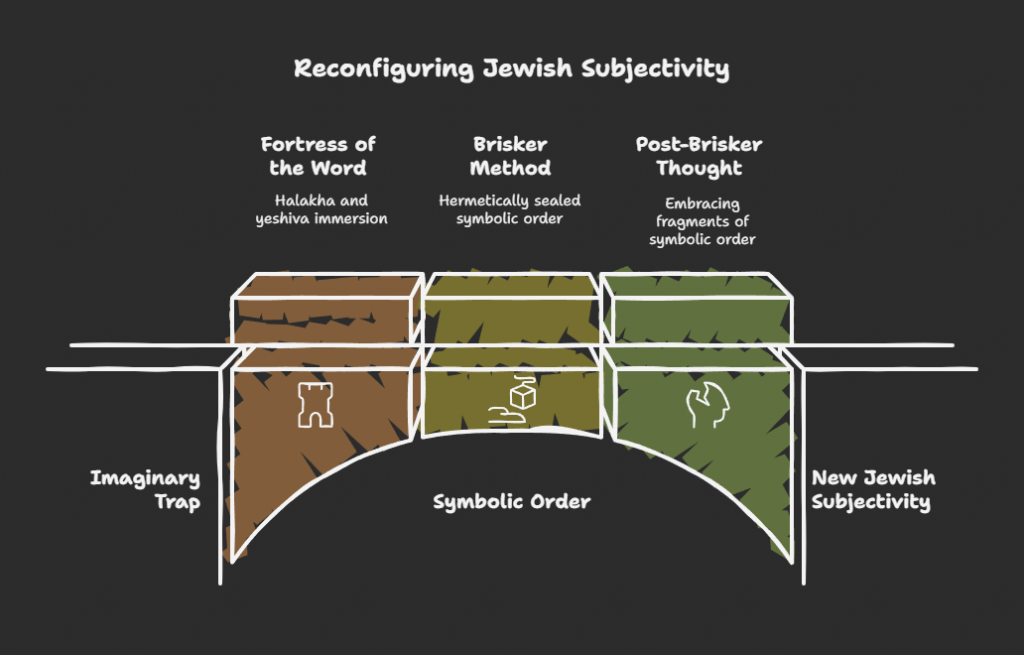

The psychic life of modern Jewish identity, as posited in the foundational analysis of “The Specular Jew: Imaginary Traps, Symbolic Defenses, and the Psychoanalysis of Modern Jewish Identity,” is constituted through a profound and unceasing dialectic.1 This dialectic operates between two fundamental psychoanalytic registers articulated by Jacques Lacan: the Imaginary and the Symbolic. The Imaginary register, the realm of the image, ego-formation, and alienating identification, manifests historically as the “Imaginary trap”—the specular, antisemitic “image of the Jew” constructed by the non-Jewish Other as a screen for the projection of its own collective shadow.1 This external, hostile gaze threatens to define and ensnare the Jewish subject in an identity that is not their own. Historically, the primary defense against this entrapment has been the construction of a powerful and totalizing Symbolic order—what the foundational paper terms the “Fortress of the Word”.1 This fortress is built from the comprehensive legal framework of Halakha and the immersive textual environment of the yeshiva, a self-contained universe of signifiers—language, law, and text—designed to ground the subject’s identity in an internally coherent system that transcends and resists the specular gaze of the Other.1

This report posits that the Brisker method of Talmudic study, innovated in the late 19th century by Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk, represents the historical and intellectual zenith of this Symbolic fortress. The Brisker derech (the “way of Brisk”) was not merely a new pedagogical technique but a revolutionary attempt to construct a pure, hermetically sealed, and perfectly self-referential Symbolic order for Halakha. Its rigorous conceptualism, analytical precision, and programmatic bracketing of empirical reality constituted the most systematic effort in modern Jewish history to forge an insulated subject, an ideal Halakhic Man whose identity would be entirely determined by the internal logic of this perfected system.

The subsequent “loss” of the Brisker movement’s unquestioned hegemony within non-Hasidic Orthodoxy cannot be understood as a simple historical decline. Rather, it must be analyzed as a structural psycho-history, a narrative of the internal pressures and eventual fracture of this perfected Symbolic order under the conditions of modernity. This report will trace this

psycho-history through three distinct stages. First, it will analyze the architecture of the Brisker method itself as the ultimate “Fortress of the Word,” a fantasmatic attempt to create a Symbolic order without the structural “lack” or inconsistency that Lacan insists is constitutive of any such system. Second, it will examine the philosophical and existential writings of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Rabbi Chaim’s grandson and the master inheritor of the tradition, as the pivotal site of the system’s crisis. His work documents the profound collision between the pure Symbolic subject forged by Brisk and the alienating demands of the modern world, a collision that produces the paradigmatic “lonely man of faith.” Finally, the report will analyze the emergence of post-Brisker thought, particularly the work of the Israeli thinker Rabbi Shimon Gershon Rosenberg (Rav Shagar), as a radical postmodern reconfiguration of the Symbolic. Rav Shagar’s thought, which directly and consciously engages with the Lacanian concepts that Brisk sought to foreclose, represents a move away from the fantasy of a perfect fortress toward a new model of Jewish subjectivity—one that attempts to live within and through the fragments of a Symbolic order that can no longer sustain the illusion of its own completeness.

Part I: The Brisker Derech as the Pure Symbolic

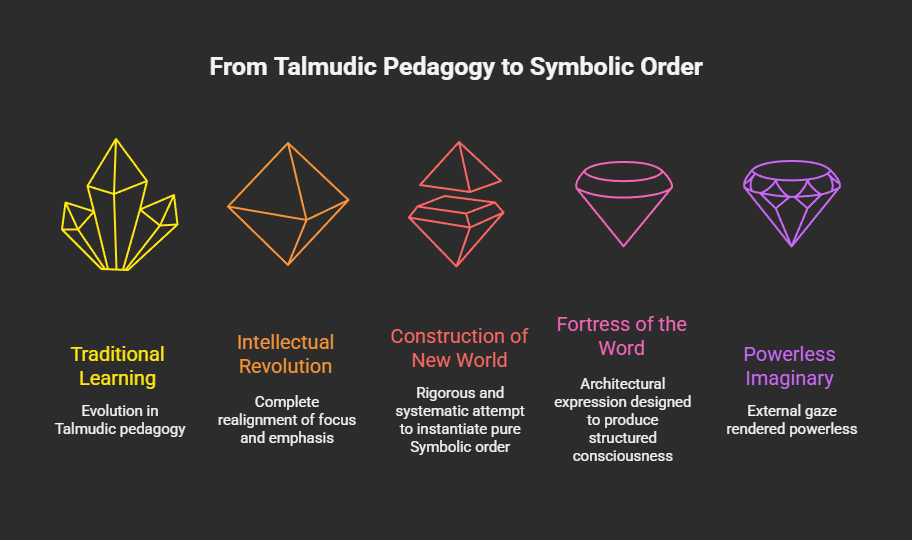

The intellectual revolution inaugurated by Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik (1853-1918) was, in the words of his grandson, comparable to the Copernican revolution in its complete realignment of focus and emphasis.2 The Brisker derech was more than an evolution in Talmudic pedagogy; it was the construction of a new intellectual world. Analyzed through a Lacanian lens, this world reveals itself as the most rigorous and systematic attempt in the modern era to instantiate a pure Symbolic order—a self-contained, logically coherent, and self-validating universe of legal signifiers. It was the ultimate architectural expression of the “Fortress of the Word,” designed to produce a subject whose consciousness was so thoroughly structured by its internal logic that the external, Imaginary gaze of the Other would be rendered powerless.

The Architecture of a Parallel Universe

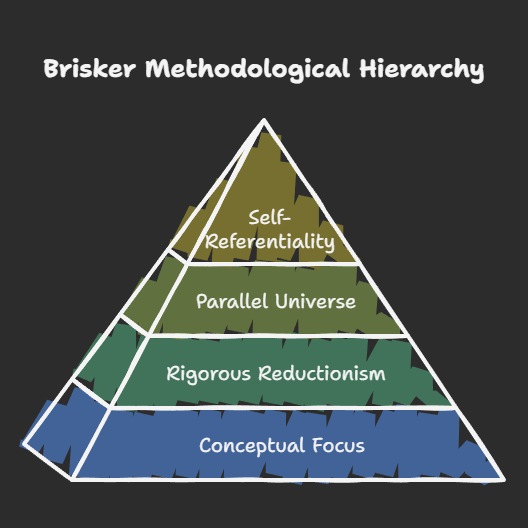

The Brisker method’s revolutionary power lies in its systematic abstraction. It is a methodology designed to extract Halakha from the contingencies of history, psychology, and even the narrative flow of the Talmudic text itself, and to reconstitute it as an autonomous, a priori system of pure concepts. This project of purification operates through several key methodological innovations.

First and most fundamentally, Rabbi Chaim shifted the focus of Talmud study from a textual and dialectical analysis to a purely conceptual one.3 Traditional Talmud study had often centered on the dynamic, unfolding process of the Gemara’s debate, the shakla ve-tarya (“taking and giving”). The Brisker derech, by contrast, largely bypasses this process to focus on the static legal conclusions and the variant positions of the Rishonim (medieval commentators).3 The goal is not to follow the conversation but to distill from its endpoint a set of underlying, abstract principles. This represents a crucial structural move from a diachronic model of discourse, which unfolds in time, to a synchronic model of a formal system, where all elements exist simultaneously in a logical relationship to one another. This shift is the first step in detaching the law from the particularities of its textual expression and elevating it to the realm of pure form.

This conceptual form is achieved through a process of rigorous reductionism and the pursuit of absolute analytical precision.6 The method is characterized by its “fierce Talmudism,” “incisive analysis,” and “exact classifications”.8 Its primary tool is the chakira (investigation or distinction), a binary conceptual categorization that seeks to resolve apparent contradictions or explain divergent legal opinions by positing a single, subtle difference in the underlying definition of a halakhic entity.6 For example, a legal obligation might be analyzed through the chakira of cheftza versus gavra (“object” versus “person”). Does the law inhere in the object itself (e.g., an incestuous relative is an inherently “forbidden person”), or does it pertain to the action of the person in relation to the object (e.g., a menstruating woman is not an inherently forbidden person, but the act of intercourse with her is forbidden for the man)?.3 By creating a new and precise terminology for these concepts, Rabbi Chaim gave his students the tools to construct and navigate this conceptual world.3 This approach has been compared to mathematics or modern science in its attempt to create a logically coherent system of definitions, axioms, and proofs, a world of pure concepts divorced from the “pots and pans” of everyday reality.3

The result of this systematic abstraction is the construction of what has been described as a “parallel universe” for Halakha.3 According to the Brisker worldview, Halakha is an a priori system whose laws relate only to themselves and are not fundamentally shaped by their interaction with empirical reality.3 The student of Brisk does not derive legal principlefrom the messy data of the world; rather, as Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik would later articulate in Halakhic Man, he approaches the world with his Torah already in hand, imposing its pre-existing grid of “fixed statutes and firm principles” onto reality.14 This a priori nature is fiercely guarded. Rabbi Chaim, for instance, strongly opposed borrowing concepts from any discipline outside of Halakha, ensuring that the system remained hermetically sealed.3

This self-referentiality is further secured by the method’s programmatic refusal to ask “why.” The Brisker analyst is concerned only with “what”—the formal mechanics, the precise definitions, and the conceptual categories of the law.3 Teleological questions about the purpose of the commandments (

ta’amei ha’mitzvot), historical questions about the development of the law, or psychological questions about the motivations of the legal actors are deemed irrelevant and illegitimate.3 The Briskers see Halakha as the expression of a transcendent and unfathomable Divine will; the goal is to understand its internal structure, not to justify it by reference to any external, human-centered logic.3 This foreclosure of the question “why” is the final and most crucial element in sealing the Symbolic fortress. It cuts off any path that might lead outside the system to an external source of meaning, ensuring that the entire intellectual enterprise remains within the self-validating circle of the Halakhic text and its conceptual superstructure.

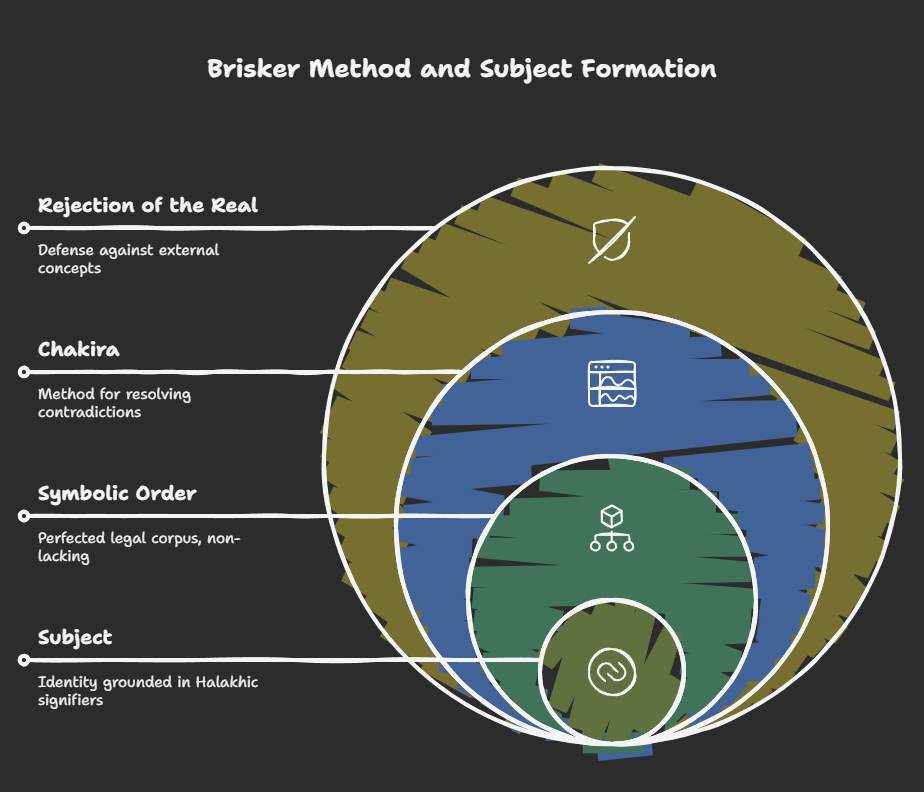

Halakha as the Non-Lacking Other

The Brisker project, when viewed through a Lacanian framework, reveals itself as a sophisticated and radical attempt to instantiate a “big Other” that is perfectly consistent, complete, and devoid of the structural “lack” that Lacan insists is constitutive of any Symbolic order. The Symbolic order, for Lacan, is the trans-individual “treasury of signifiers”—the system of language, law, and culture—that pre-exists and structures the subject.1 The subject finds their identity only by taking up a position within this signifying chain. However, Lacan’s crucial insight is that this Symbolic order, this “big Other,” is not a seamless, coherent whole. It is inherently inconsistent, riddled with contradictions, and founded upon a void—a “lack in the Other”.1 There is no ultimate signifier to guarantee the meaning of all other signifiers, no final metalanguage that can ensure the system’s total coherence. The Brisker method can be understood as a profound, albeit fantasmatic, rebellion against this fundamental lack.

The primary mechanism for constructing this non-lacking Other is the relentless application of the chakira. The traditional approach to Talmud study accepted that contradictions between texts might exist, requiring reinterpretation to reconcile them.6 The Brisker method elevates this reconciliation to an absolute principle. Its genius lies in its ability to take any two seemingly contradictory rulings and demonstrate that they are, in fact, perfectly consistent once a single, underlying conceptual distinction is identified.6 A whole series of debates between two great medieval authorities can be shown to revolve around one subtle difference in their abstract understanding of a legal principle.6 This technique functions as a powerful psychic defense, a way of “papering over” any hole or inconsistency in the fabric of the Symbolic. Every apparent rupture is shown to be merely an illusion, a failure of analysis that disappears under the bright light of conceptual precision.2 The result is the production of a fantasy-object: a perfectly coherent, non-contradictory, and seamless legal corpus, a “big Other” that always has the answer and is never at a loss.

This hermetic perfection is defended by a structural rejection of the empirical and the contingent—that which Lacan terms the Real. The Brisker method’s staunch refusal to incorporate external concepts from history, science, or psychology is a crucial defense mechanism.3 It prevents the messy, unpredictable, and often traumatic contingency of the Real from piercing the pristine, logical fabric of the Symbolic. Even the material text of the Talmud itself is, in a sense, bracketed; the Brisker is not concerned with manuscript variations or the historical development of the text, because the concepts are seen as ideal and eternal, existing independently of their particular textual instantiation.3 This creates a system that is, by design, unfalsifiable by any external data, a fortress of pure reason secure against the incursions of a chaotic world.

The ultimate purpose of this architecture is the forging of a particular kind of subject. The yeshiva, as the institution where this method is transmitted, becomes a factory for producing a subject whose identity is grounded entirely within this totalizing chain of signifiers.1 The immersive, argumentative process of Talmud study, supercharged by the Brisker method’s conceptual rigor, molds the student’s entire mode of thought.1 This aligns perfectly with the “Fortress of the Word” thesis, which posits that the traditional yeshiva system functions to insulate the subject from the Imaginary by grounding identity in law and language. The Brisker method is the ultimate technology for achieving this goal. It aims to produce a subject so thoroughly interpellated by the internal system of Halakhic signifiers, so completely defined by his position within this perfected Symbolic order, that the hostile, defining, specular gaze of the external, Imaginary Other simply ceases to matter. The fortress is so thick, the internal world so complete, that the outside world and its alienating images become irrelevant noise.

Part II: The Soloveitchik Dialectic: The Subject of Brisk Confronts Modernity

The intellectual and spiritual legacy of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903-1993), known universally in the world of Modern Orthodoxy as “The Rav,” represents the pivotal moment of crisis for the Brisker Symbolic order. As the scion of the Brisker dynasty and the master inheritor of its methodology, The Rav was uniquely positioned to articulate its deepest philosophical premises.2 Yet, as a man who also earned a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Berlin and lived his life as a public leader in 20th-century America, he was also forced to confront the collision of this hermetic system with the complex demands of the modern world.19 His two most famous philosophical works, Halakhic Man and The Lonely Man of Faith, are not merely sequential essays but represent the two poles of a profound dialectic. Together, they document the theoretical perfection of the Brisker Symbolic subject and the unbearable psychic cost of that perfection when the walls of the fortress can no longer hold back the world.

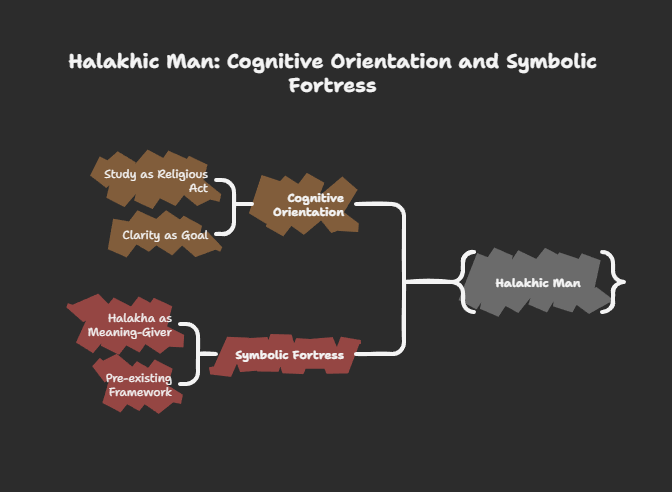

Halakhic Man: The Ideal Subject of the Symbolic

Published in Hebrew in 1944, Ish ha-Halakhah (Halakhic Man) stands as the definitive philosophical portrait of the ideal subject produced by the Brisker system. It is a work of profound intellectual power that elevates the Brisker method from a mere style of learning into a comprehensive worldview and a distinct human typology. The essay is both a description of and a product of the Brisker derech, employing its characteristic use of abstract categorization and halakhic metaphor to define the very personality it seeks to describe.2

The Rav’s central thesis is the delineation of “Halakhic man” as a distinct cognitive type, a unique synthesis of homo religiosus (religious man) and the scientist.10 Unlike the naive religious consciousness that experiences the world with spontaneous wonder, or the aesthetic consciousness that is moved by its beauty, Halakhic man approaches reality as a cognitive problem to be solved.10 He comes to the world not with an open heart but with an a priori system of Halakhic categories, a set of ideal conceptual templates that he seeks to impose upon the chaotic data of sensory experience.14 In The Rav’s memorable formulation: “When halakhic man approaches reality, he comes with his Torah, given to him from Sinai, in hand. He orients himself to the world by means of fixed statutes and firm principles. An entire corpus of precepts and laws guides him along the path leading to existence”.14 This is a perfect philosophical articulation of the Brisker project. The world does not give meaning to Halakha; Halakha gives meaning to the world. The subject does not discover reality; he actively constitutes it through the application of a pre-existing, transcendent, legal-conceptual framework.

This cognitive orientation means that for Halakhic man, the ultimate religious act is study, and the ultimate goal of study is clarity. In a eulogy for his uncle, The Rav described the effect of the Brisker method as a sudden shining of great light, where perplexity disappears and crooked roads are made straight.2 Halakhic Man universalizes this experience. The ideal subject of this system is one who transforms the entirety of existence—the natural world, human relationships, the flow of time—into a text to be analyzed, categorized, and understood through the lens of Halakha. His relationship with God is not primarily emotional or mystical but intellectual; he connects to the Divine will by comprehending the intricate, logical structure of the law. This figure is the Brisker method personified: a being whose consciousness has been so thoroughly molded by the system’s demand for conceptual precision, rigorous analysis, and intellectual boldness that his very mode of being in the world becomes an extension of the methodology itself.2 He is the triumphant inhabitant of the Symbolic fortress, a subject whose identity is perfectly and completely secured by his position within the non-lacking Symbolic order of Halakha.

The Lonely Man of Faith and the Return of the Repressed

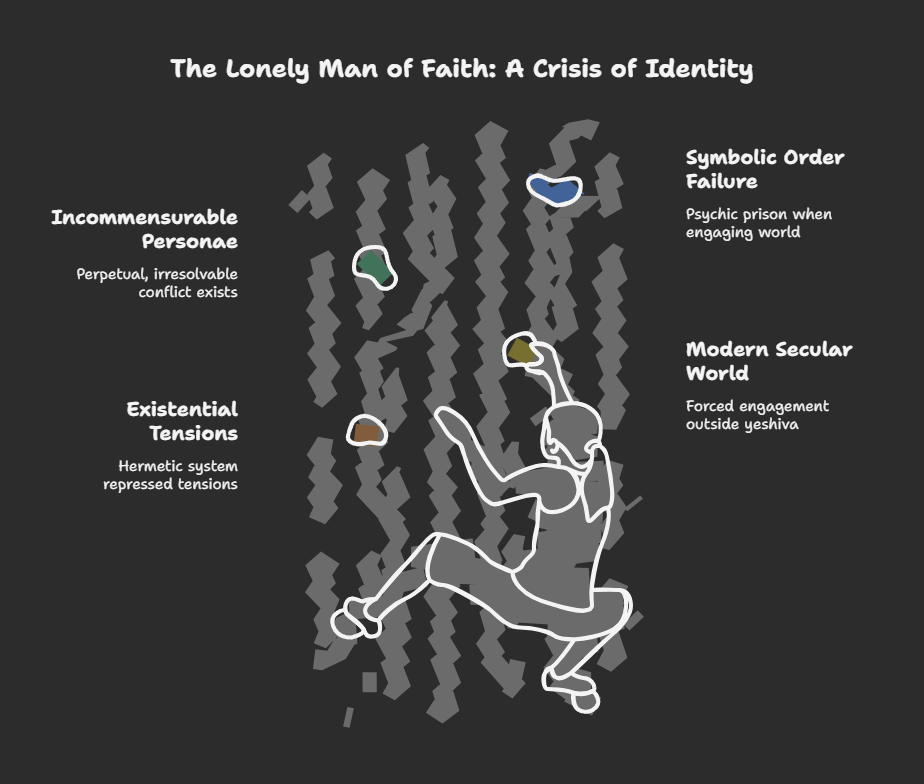

If Halakhic Man describes the triumphant subject of a perfected Symbolic order, The Lonely Man of Faith, first published in 1965, documents the “return of the repressed”—the eruption of the profound existential tensions that the hermetic Brisker system sought to foreclose.19 Written for an interfaith audience and drawing heavily on Western existentialist philosophy, the essay reveals the psychic cost of the Brisker project when its subject is forced to step outside the walls of the yeshiva and engage with the modern, secular world.10 The central dialectic of the essay, between two archetypal aspects of human nature which The Rav calls “Adam the first” and “Adam the second,” can be read as a powerful psychoanalytic symptom, a dramatization of the structural conflict between the Symbolic and the Imaginary registers of existence.

The Rav’s analysis begins with the two creation narratives in Genesis.22 “Adam the second,” created from the “dust of the earth” in Genesis 2, represents the covenantal man of faith. He is defined by his quest for redemption, his awareness of his own incompleteness, and his yearning for an intimate relationship with God.24 He exists within a “covenantal faith community,” a community bound not by utilitarian goals but by a shared commitment to a transcendent, revealed Law.24 This Adam II is, in essence, a more existentially rendered version of Halakhic man. He is the subject of the Symbolic order, defined by his relationship to the pre-existing covenant (the Law) and seeking meaning and redemption through submission to its structure.

“Adam the first,” by contrast, is the “majestic man” of Genesis 1, created in God’s image and commanded to “fill the earth and subdue it”.22 He is defined by his quest for “dignity,” which he achieves through creative mastery, technological control over the environment, and success within a “natural work community”.24 Adam I embodies the subject’s necessary but alienating engagement with the modern world—a world The Rav describes as “narcissistic, materially oriented, [and] utilitarian”.19 This is a perfect description of the Lacanian Imaginary: the register of the ego, of social recognition, of status, of utility, and of the constant dialectic of competition and comparison with the Other. Adam I is the subject as he is reflected in the mirror of society, judged by his achievements and his ability to exercise power. This is the very realm of the specular image and the gaze of the Other that the Brisker fortress was built to defend against.

The Rav’s central, tragic thesis is that the person of faith is commanded by God to be both Adam I and Adam II, but that these two personae are fundamentally incommensurable and exist in a state of perpetual, irresolvable conflict.24 The result is an inescapable and profound “loneliness”.22 From a Lacanian perspective, this loneliness is not a mere emotion but the subjective experience of the split subject ($), the barred subject of the Symbolic who can never be fully represented in language or find a complete, unified image of himself. The “lonely man of faith” is torn between the internal coherence of his Symbolic identity (Adam II) and the demands and definitions of the external Imaginary order (Adam I). He can find no mirror in the utilitarian, majestic world of Adam I that reflects the redemptive, covenantal reality of Adam II. His very being is split across two registers that do not speak the same language.

The trajectory from Halakhic Man to The Lonely Man of Faith, therefore, documents the structural failure of the “pure Symbolic” project. The Brisker fortress, designed to be an impenetrable sanctuary, proves to be a psychic prison when its inhabitant must engage with the world. The “loneliness” The Rav describes is the precise psychic cost of maintaining a rigid, all-encompassing Symbolic identity in a world dominated by the logic of the Imaginary. The fortress walls, meant to keep the Other’s defining gaze out, also prevent the subject from finding any coherent, validating reflection of his deepest self within the social world. Rabbi Soloveitchik’s work thus serves as the crucial pivot in this intellectual history. He provides the ultimate philosophical defense of the Brisker Symbolic and, simultaneously, the most profound psychoanalytic testimony to its untenability in the face of modernity. He documents the beginning of the “thinning of the Symbolic” not as a theological choice (as the foundational paper describes for Reform Judaism), but as a traumatic, unavoidable, and deeply personal encounter with the fractured nature of the modern self.1

Part III: The Thinning of the Fortress: Post-War Shifts and the Postmodern Turn

The existential crisis so powerfully articulated in Rabbi Soloveitchik’s work was not merely a private philosophical dilemma; it was a symptom of broader historical and sociological pressures that were beginning to challenge the hegemony of the Brisker method in the post-war era. The very insularity that had made the Brisker Symbolic fortress such a powerful defense mechanism in the crucible of Eastern Europe became a source of tension and critique within the new context of American Modern Orthodoxy. This section will trace the consequences of this crisis, arguing that the waning influence of the pure Brisker model was a direct result of its structural inability to address the needs of a new generation of Jewish subjects. This intellectual vacuum, in turn, paved the way for the emergence of new paradigms—most radically in the work of Rav Shagar—that consciously abandoned the quest for a perfect, sealed system and instead sought to reconfigure the Symbolic order to account for subjectivity, experience, and the “lack” it had long sought to deny.

The Sociological Crisis of Abstraction

The decades following the Second World War witnessed a profound transformation in the landscape of American Orthodoxy. The mass migration of Jews to the suburbs, the decline of overt antisemitism, and the increasing integration of Orthodox Jews into the professional and cultural life of the United States created a new social reality.25 For this emerging community, particularly within the stream that would come to be known as Modern Orthodoxy, the central challenge was no longer insulation but engagement. The new ethos, championed by institutions like Yeshiva University where Rabbi Soloveitchik taught, was one of bringing Torah to the world, of synthesizing Jewish tradition with Western thought and modern life.20 Within this new context, the Brisker method’s programmatic abstraction and “other-worldliness” began to be perceived not just as a methodological choice but as a philosophical problem.13 A significant critique emerged from within Modern Orthodoxy, arguing that there was a “huge tension” between the Brisker philosophy and the worldly engagement the movement championed.13 The Brisker view of Torah as an “abstract, pure and non relevant” system seemed diametrically opposed to the Modern Orthodox belief in a Torah that could “speak to, empower, and inspire this world”.13 The tendency of the most rigorous

Brisker yeshivas, particularly the Jerusalem branch of the Soloveitchik family, to focus exclusively on the Talmudic tractates dealing with Temple sacrifices (Seder Kodshim) was seen as the ultimate expression of this disengagement. Kodshim was “Brisk at its purest”—an ethereal, conceptual world untainted by human realities, and thus a perfect subject for abstract analysis, but one with almost no practical relevance to modern life.13

This philosophical tension was accompanied by a growing existential dissatisfaction. The Brisker method’s exclusive focus on the “what” of the law, at the expense of the “why,” left a vacuum of meaning, emotion, and personal religious experience that newer generations, raised in a culture that prized individualism and authenticity, sought to fill.3 Critics began to argue that the method’s intense intellectualism could come at the expense of character development (middot) and a deeper relationship with God.3 The system that had been perfected to create the ultimate cognitive subject was proving ill-equipped to nourish the complete human being. This created a fertile ground for alternative approaches—from the Telzer method’s focus on the “perfection of the self” 29 to the neo-Hasidic revival—that prioritized precisely the existential and subjective questions that Brisk had methodologically excluded.

Table 1: A Comparative Typology of Talmudic Methodologies as Symbolic Systems

| Feature | The Brisker Derech (R. Chaim Soloveitchik) | The Soloveitchik Dialectic (R. J.B. Soloveitchik) | The Postmodern Turn (Rav Shagar) |

| Core Intellectual Project | Conceptual analysis; creation of a pure, a priori Halakhic system.3 | Philosophical articulation of the Halakhic system and diagnosis of its existential crisis in modernity.10 | Synthesis of Talmud with Hasidut, psychoanalysis, and postmodernism to find personal meaning.30 |

| View of the Symbolic Order | A perfect, non-lacking,self-referential “Fortress”.3 | A coherent but demanding internal order (Adam II) in irreconcilable conflict with the | An inherently fragmented, “lacking” system that must be creatively and |

| external world (Adam I).24 | subjectively reassembled.32 | ||

| The Ideal Subject | The Halakhic Man: a purely cognitive being who imposes law on reality.10 | The Lonely Man of Faith: a split subject ($) torn between two incommensurable identities.22 | The Paradoxical Subject: a “schizophrenic” being who lives within and embraces contradiction.34 |

| Relation to the World/Imaginary | Foreclosure/Bracke ting: The external world is irrelevant to the system.3 | Traumatic Encounter/Alienatio n: The world is a source of utilitarian demands that alienate thefaith-subject.19 | Dialogic Engagement/Appro priation: The world’s philosophies (Lacan, postmodernism) are tools for reinterpreting Torah.30 |

| Key Question | “What?” (Vos?) – The mechanics of the law.3 | “How can one be both?” – The existential dilemma of the split self. | “What does this mean for me?” (Mashmaut) – The quest for subjective relevance.31 |

The Counter-Gaze of Rav Shagar: Embracing the Lack

The most radical and theoretically sophisticated response to the crisis of the Brisker legacy can be found in the work of the Israeli Religious-Zionist thinker, Rabbi Shimon Gershon Rosenberg (1949-2007), known as Rav Shagar. His thought represents a complete inversion of the Brisker project. Where Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik sought to build a perfect Symbolic order that would foreclose any lack or contradiction, Rav Shagar’s project is to construct a meaningful Jewish life precisely within and through an acceptance of the “lack in the Other.” His work constitutes a postmodern, and explicitly psychoanalytic, counter-gaze to the modernist certainty of Brisk.

The most startling feature of Rav Shagar’s thought is his direct and deliberate incorporation of Lacanian psychoanalysis into his theological and hermeneutic framework.30 This represents a monumental shift. The Brisker system is structurally pre-psychoanalytic (or even anti-psychoanalytic), in that its entire purpose is to create a purely cognitive subject and to bracket questions of desire, subjectivity, and the unconscious. Rav Shagar, by contrast, places these questions at the very center of his inquiry. He explicitly links the Lacanian concept of “the Real”—the pre-symbolic, undifferentiated order that resists symbolization—with kabbalistic ideas to define a new phenomenology of faith.30 For Rav Shagar, faith is not located in the clear, logical propositions of the Symbolic order, but in the encounter with that which the Symbolic cannot contain—the Real. This is a profound move away from a religion of intellectual certainty to a religion of mystical encounter with the limits of reason.

This theoretical shift has direct methodological consequences. Rav Shagar explicitly called for a reversal of the Brisker priority, shifting the focus of learning from the objective nature of the law (cheftza) to the subjective experience of the person (gavra).31 He argued that for the postmodern Jew, the central religious need is not for abstract legal formulation but for

mashmaut—personal meaning.31 He contended that the alienation many young religious Israelis felt from Talmud study was a direct result of a pedagogy (heavily influenced by the Brisker model) that presented the text as a set of irrelevant, abstract problems, thereby failing to connect with their inner lives.35 His proposed solution was to broaden the field of study, integrating Hasidut, literature, Jewish thought, and even secular humanities into the process of learning Talmud, using imagination and emotion alongside intellect.31

Furthermore, in stark contrast to the Brisker obsession with resolving contradictions to create a single, unifying conceptual framework, Rav Shagar, drawing on postmodern thought, embraces multiplicity, dissent, and paradox.30 He sees the modern religious personality not as a unified “Halakhic Man” but as a “schizophrenic” subject who must learn to hold multiple, conflicting worldviews in a state of creative tension.34 This is a radical acceptance of the Lacanian “split subject” as the normative condition of modernity, rather than as a problem to be solved or a flaw to be mended. For Rav Shagar, the attempt to create a single, harmonious, and internally consistent identity is a futile and misguided modernist project. The task of the contemporary person of faith is to learn to live with the fragments.

A New Symbolic Configuration

The post-Brisker turn, exemplified most powerfully by Rav Shagar, should not be understood as a simple “thinning” of the Symbolic order, analogous to the move toward individual autonomy in Liberal Judaism as described in “The Specular Jew”.1 While it shares with Liberal Judaism a turn toward the subject, it is not a simple abandonment of the totalizing structure of Halakha. Instead, it represents a fundamental reconfiguration of the Symbolic order itself. It is a conscious attempt to construct a system that can remain traditionally grounded while incorporating, rather than foreclosing, the subject’s inevitable and traumatic encounter with the Imaginary and the Real.

The Brisker Symbolic is, in its essence, a monologue. It is a system that speaks to itself, in its own language, according to its own rules. Rav Shagar’s approach, by contrast, creates a dialogic Symbolic order.31 By insisting on the integration of Hasidut, literature, philosophy, and psychoanalysis into the very act of Talmud study, he creates a system that is porous by design, one that is constantly in conversation with the intellectual and cultural currents of the external world. It does not seek to bracket the Imaginary register of modern culture but to enter into a critical and interpretive dialogue with it, using its concepts (like those of Lacan) as tools for unlocking new layers of meaning within the traditional texts.30

This results in a profound subjectivization of the Symbolic. By prioritizing personal meaning (mashmaut) and individual creativity in interpretation, the post-Brisker approach re-centers the Symbolic order around the subject’s existential experience.31 The Law is no longer merely an objective, external grid to be applied from on high, but a text that must be made personally relevant, a “Torah of life” that speaks to the individual’s deepest concerns, in order to become truly authoritative. This mirrors, in a more traditionally-bound and textually-centered frame, the shift toward individual autonomy described in the foundational paper’s analysis of Reform Judaism.1 It is an acknowledgment that in the modern world, the authority of the “big Other” can no longer be taken for granted; it must be constantly re-established and re-authorized through the creative and interpretive engagement of the subject.

This shift can be understood as a move from a paranoid Symbolic structure to a postmodern one. The Brisker method, in its relentless quest for a perfect, non-lacking, and internally consistent Other, has a paranoid structure in the psychoanalytic sense. It is a rigid, fantasmatic system built with immense intellectual force to defend the ego against a hostile and chaotic outside world, a world that threatens to reveal the system’s own internal contradictions. Rav Shagar’s thought, by contrast, begins from the premise that the “lack in the Other” is a given. He abandons the fantasy of a perfect, impregnable fortress and instead develops a strategy for living within the ruins. His method involves using the fragments of tradition, philosophy, and psychoanalysis to construct a provisional, paradoxical, and deeply personal Symbolic dwelling. This is not a “thinning” of the Symbolic, but a conscious attempt to build a Symbolic order after the death of the Master Signifier, after the loss of the belief in an ultimate guarantee. It offers a different, more complex, and perhaps more psychologically resilient strategy for navigating the unceasing dialectic between the Symbolic and the Imaginary than the brittle perfection of Brisk.

Conclusion: From Purity to Paradox

This analysis has traced the intellectual and psychic trajectory of the Brisker movement through a Lacanian lens, reframing its history as a structural transformation in the nature of the Orthodox Jewish Symbolic order. The initial thesis of “The Specular Jew,” which posits a fundamental dialectic between an externally imposed Imaginary identity and an internally generated Symbolic one, provides the essential framework for this narrative.1 The Brisker derech, innovated by Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, emerges in this reading as the apotheosis of the “Fortress of the Word”—a monumental effort to construct a pure, self-referential, and non-lacking Symbolic system capable of producing a subject entirely insulated from the hostile gaze of the Other. Its analytical rigor and programmatic abstraction were the tools used to build a “parallel universe” of Halakha, a perfected Symbolic order designed to be logically impenetrable.

The philosophical work of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik marks the moment of this system’s profound internal crisis. Halakhic Man serves as the ultimate philosophical articulation of the ideal Brisker subject, a cognitive being who constitutes reality through the application of an a priori legal grid. Yet, The Lonely Man of Faith provides the devastating testimony of this subject’s collision with modernity. The irreconcilable split between the majestic “Adam I” (the subject in the Imaginary) and the covenantal “Adam II” (the subject of the Symbolic) reveals the immense psychic cost of the Brisker fortress. The very walls built for protection become the source of a profound and inescapable alienation, documenting the structural untenability of a pure Symbolic identity in a world dominated by the Imaginary.

The subsequent “loss” of Brisk’s hegemony is thus not a simple failure but a necessary and illuminating structural evolution. The post-war sociological context of American Modern Orthodoxy, with its emphasis on worldly engagement, rendered the method’s insularity untenable for many, creating a demand for the very dimensions of meaning and subjectivity that Brisk had excluded. This intellectual vacuum was filled by new approaches, culminating in the postmodern turn exemplified by Rav Shagar. His work represents a radical reconfiguration of the Symbolic. By consciously incorporating psychoanalysis, philosophy, and a focus on personal meaning, and by embracing paradox and fragmentation rather than seeking their resolution, Rav Shagar abandons the paranoid fantasy of a perfect fortress. He instead develops a methodology for constructing a provisional, dialogic, and subjective Symbolic dwelling from within the acknowledged “lack in the Other.”

The intellectual lineage from Rabbi Chaim’s pure Symbolic, through Rabbi Soloveitchik’s articulation of its inherent crisis, to Rav Shagar’s postmodern embrace of paradox, therefore maps the profound psychic journey of a major stream of Orthodox thought as it grapples with modernity. This trajectory serves as a powerful and detailed case study, extending and complicating the thesis of “The Specular Jew.” It demonstrates how a Symbolic order, when pushed to the logical extreme of its own perfection, ultimately fractures under the pressure of the Real and the Imaginary, and must be reconfigured to account for the very subjectivity, contingency, and contradiction it initially sought to eliminate. The story of Brisk is the story of the unceasing dialectic between the fortress and the mirror, a testament to the perpetual and necessary negotiation between the alienating image reflected by the Other and the demanding, fragmenting, yet ultimately identity-giving call of the Symbolic Law.

Works cited

- Psychoanalysis and Jewish Identity’s Traps.pdf

- Rabbi Soloveitchik on the Brisker Method – Amazon S3, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/webyeshivamedia/Jeffrey+Saks+Bibliography/ R a b b i + S o l ove i tc i k + o n + t h e + B r i s ke r + M et h o d . p d f

- The Methodology of Brisk – My Jewish Learning, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://w w w.myjewishlearning.com/ar ticle/the-methodology-of-brisk/

- The World of Brisk – The Together Plan, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.thetogetherplan.com/the-world-of-brisk/

- Why does the Brisker Derech focus on the Rambam? – Mi Yodeya – Stack Exchange, accessed on September 25, 2025,htt p s : // j u d a i s m . s t a c kex c h a n g e .co m /q u e s t i o n s /6 8 6 4 3 /w hy- d o e s – t h e – b r i s ke r- d e rec h – fo c u s – o n – t h e – ra m b a m

- Brisker method – Wikipedia, accessed on September 25, 2025,htt p s : //e n .w i k i p e d i a .o rg /w i k i / B r i s ke r_ m et h o d

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed on September 25, 2025,htt p s : //e n .w i k i p e d i a .o rg /w i k i / B r i s ke r_ m et h o d # : ~ : text =T h e % 2 0 B r i s ke r % 2 0 m et h o d% 2 C % 2 0 o r % 2 0 B r i s ke r, a n d % 2 0 s p re a d % 2 0 to % 2 0 ye s h iva s % 2 0 w o r l d w id e .

- Brisk: The Mastery & the Mystery – Mishpacha Magazine, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://mishpacha.com/brisk-the-master y-and-the-myster y/

- Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik of Brisk – Sefaria, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.sefaria.org/sheets/50640

- Soloveitchik, Joseph Baer – Encyclopedia.com, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and– m a p s /s o l ove i tc h i k – j o s e p h – b a e r

- Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk – Marking 100 Years Since His Passing – Chabad.org, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.chabad.org/librar y/ar ticle_cdo/aid/4097363/jewish/Rabbi-Chaim-Solove i tc h i k – of – B r i s k . ht m

- The Rav and the Brisker Derech: A Unique Method – Jewish Action, accessed on September 25, 2025,htt p s : // j e w i s h a c t i o n .co m / t h e – rav/rav- b r i s ke r – d e re c h – un iq u e – m et h o d /

- Why Briskers Learn Kodshim – And What It Means For Modern …, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.torahmusings.com/2015/01/briskers-learn-kodshim-means-modern–or thodoxy/

- Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s Lectures on Genesis, I through V – Hakirah, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://hakirah.org/vol27Triebitz.pdf

- Of Concepts and Precision: Understanding Torat Brisk – Kol Hamevaser, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://w w w.kolhamevaser.com/2017/11/origins-of-brisk/

- Structuralism and Brisk – YUTOPIA, accessed on September 25, 2025,htt p s : // j o s hy u te r.co m / 2 0 0 3 / 1 2 / 2 1 /ra nd o m – a c ts – of- s c h o la rs h ip /s t r uc t ura lis m – a n d –b r i s k /

- Rabbi Soloveitchik – Maimonides School, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.maimonides.org/rabbi-soloveitchik

- A Haredi Attack on Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik: A Battle over the …, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://histor y.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/brisker_legacy.pdf

- The Lonely Man of Faith by Joseph B. Soloveitchik – Goodreads, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.goodreads.com/book/show/194094.The_Lonely_Man_of_Faith

- Joseph B. Soloveitchik | Research Starters – EBSCO, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://w w w.ebsco.com/research-star ters/histor y/joseph-b-soloveitchik

- Repentance and the Reversal of Time: Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s Temporal Philosophy, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.mdpi.com/2077-1444/16/6/771

- The Lonely Man of Faith | Jewish Book Council, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.jewishbookcouncil.org/book/the-lonely-man-of-faith

- The lonely man of faith – Brooklyn Public Library, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://discover.bklynlibrar y.org/item?b=11866480

- The Lonely Man of Faith – Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.tehillim.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Ziegler-Introduction-to-Lo n e l y- M a n – of – Fa i t h . p d f

- Postwar Judaism | The Pluralism Project, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://pluralism.org/post war-judaism

- (PDF) Post-World War II Orthodoxy – ResearchGate, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.researchgate.net/publication/374197239_Post-World_War_II_Or thodox y

- Reflections on 50 Years of the Sociological Study of American Jewry: Statics and Dynamics 2020 Marshall Sklare Award Address – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ar ticles/PMC8290376/

- Joseph B. Soloveitchik | Texts & Source Sheets from Torah, Talmud and … – Sefaria, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.sefaria.org/topics/joseph-b-soloveitchik

- Brisk and Telz – Kol Hamevaser, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.kolhamevaser.com/2010/12/brisk-and-telz/

- Israel’s paradoxical man of faith, deconstructed | The Times of Israel, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.timesofisrael.com/israels-paradoxical-man-of-faith-deconstructed/

- Rav Shagar-B’Torato Yehageh: The Study of Talmud as a Quest for …, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://kav vanah.blog/2011/09/02/rav-shagar-btorato-yehageh-the-study-of-talmud-as-a-quest-for-god-par t-i/

- A Torah of Fragments: An Explication of Rabbi Shimon Gershon Rosenberg (SHaGaR)’s Hermeneutical Methodology, accessed on September 25, 2025,htt p : //s h a g a r.co. i l /w p – co nte nt /u p l o a d s /A-Tora h – of- Fra g m e nts -Av i d a n – H a livn i-Th es i s . p d f

- The Earth-Shattering Faith of Rav Shagar | The Lehrhaus, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://thelehrhaus.com/scholarship/the-ear th-shattering-faith-of-rav-shagar/

- 1 Eitan Abramovitch The Institution for the Advancement of Rav Shagar’s Writings “’Dispute for the sake of heaven’ – Creighton University, accessed on September 25, 2025,https://w w w.creighton.edu/sites/default/files/2022-03/klutznick-abstracts-2018.pd f

- Rav Shagar: Studying Torah as a Quest for God – םישדח םיפוריצ, accessed on September 25, 2025, https://zerufim.siach.org.il/en/studying-torah-as-a-quest-for-god/