Introduction: A Complaint Addressed to the Divine Other

The desire to convert to Judaism, or gerut, is conventionally understood as a spiritual journey toward faith and community. This report, however, proposes a more unsettling psychoanalytic interpretation. It frames the desire for conversion not as a simple quest, but as a complex psychic event rooted in a profound narcissistic injury. The prospective convert, confronting the contingency of their birth, implicitly posits that the Divine Other has made an error—an error which the act of conversion hubristically seeks to rectify. The unspoken complaint, “I should have been born a Jew,” is a defense against a more fundamental psychic wound, an attempt to rewrite one’s own origins and correct a perceived flaw in the divine plan.1

This analysis will argue that this individual act of hubris, when aggregated through contested or “loose” conversion standards, precipitates a collective regression for Klal Yisrael (the totality of the Jewish people). This regression is characterized by a shift away from the stability of the Symbolic order—defined by the shared covenant and the structuring principles of halakha (Jewish law)—and toward the volatile and narcissistic dynamics of the Imaginary order. This internal psychic shift within the collective body of Israel finds its external political expression in the posture of the modern State of Israel. As its internal symbolic cohesion weakens, the nation-state becomes pathologically dependent on the gaze of the Other, perpetually seeking validation in the “mirror of the nations.”

To develop this argument, this report will proceed in four parts. Part I will establish the foundational psychoanalytic frameworks of Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan, contrasting their respective approaches to religion to build the necessary theoretical apparatus. Part II will apply this framework to the individual psychology of the convert, analyzing gerut as an act of narcissistic rectification. Part III will broaden the scope to the collective, examining how the contemporary crisis in conversion standards threatens the symbolic integrity of Klal Yisrael. Finally, Part IV will connect this internal crisis to the political psychoanalysis of Israeli national identity, demonstrating how a fractured internal order leads to a precarious dependency on external recognition.

Part I: The Psychoanalytic Subject and the Divine Other: Freudian and Lacanian Frameworks

To analyze the complex psychic dynamics of conversion and its impact on collective identity, it is first necessary to establish the psychoanalytic lens through which religion is viewed. The transition from Sigmund Freud’s psychodynamic critique to Jacques Lacan’s structural analysis provides the essential theoretical progression for this report’s thesis.

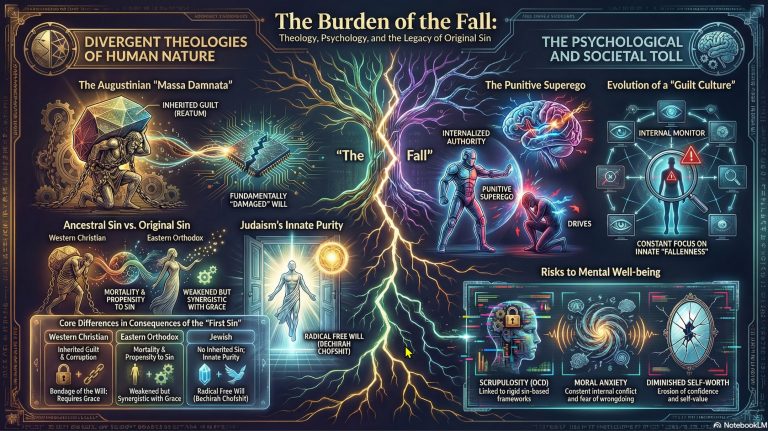

The Freudian Father and the Illusion of Religion

Sigmund Freud’s engagement with religion is famously critical, portraying it as a phenomenon rooted in the earliest stages of human psychological development. He characterized religious belief as a “universal obsessional neurosis,” wherein the repetitive, detailed nature of religious rituals mirrors the compulsive actions of a neurotic individual attempting to manage unconscious guilt and anxiety.2 For Freud, these beliefs are not arbitrary but serve a distinct purpose: they are wish-fulfilling illusions. God is fundamentally a projection of the infantile need for a powerful, protective father figure—an “exalted father”—who can shield the helpless individual from the overwhelming forces of nature and the discontents inherent in civilization.3

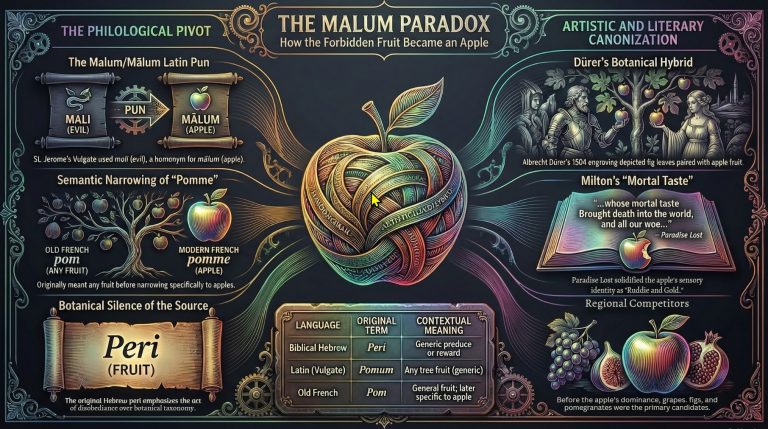

In Totem and Taboo, Freud constructed a speculative psycho-history of religion, tracing its origins to the guilt following a primal act of patricide, where a band of brothers killed and devoured their father to gain access to his power and his women.2 The subsequent totem meal—the symbolic reenactment of this act—became, in Freud’s view, the genesis of social organization, moral restriction, and religion itself. This narrative is crucial because it informed his later, more nuanced position. In an afterword to his Autobiographical Study, Freud conceded that religion’s enduring power lies not in its “material truth” but in its “historical truth”.2 This “historical truth” is the repressed, traumatic memory of the primal crime, which returns in the distorted form of religious law and ritual. This idea, that a foundational (even if fictional) event structures subsequent law and social reality, serves as a critical bridge to a Lacanian understanding of the Symbolic order. Freud’s own relationship with Judaism was marked by this same complexity; though “completely estranged from the religion of his fathers,” he maintained that he remained “in his essential nature a Jew,” acknowledging the “dark emotional powers” and intellectual tradition that shaped him.2

The Lacanian Orders and the Function of Belief

Jacques Lacan, while claiming a “return to Freud,” fundamentally reoriented the psychoanalytic approach to religion. He shifted the analysis from the psychological content of belief to its structural function in constituting the subject’s reality. This reality is organized through three interlocking orders: the Real, the Symbolic, and the Imaginary.9 The Real is the traumatic, unsymbolizable kernel of existence that resists language and meaning. The Symbolic is the realm of language, law, culture, and social structures—what Lacan calls the “big Other”—which imposes a grid of meaning onto the Real, thereby creating a coherent reality for the subject. However, the Symbolic is itself founded upon a fundamental lack; it can never fully capture the Real. The Imaginary is the realm of images, identification, and the ego. It is governed by the logic of the mirror, where the subject forms an illusory sense of a whole, unified self by identifying with an external image, leading to dynamics of rivalry, jealousy, and narcissistic demand.11

Within this framework, Lacan’s famous statement, “God is unconscious” 13, does not mean God is a repressed thought. It means that the function of “God” operates at the level of the unconscious structures that govern reality. God functions as a master signifier, the “Name-of-the-Father,” which anchors the entire Symbolic order.14 This master signifier guarantees the coherence of the big Other, suturing the gaps and contradictions in language and law, and thereby providing the subject with a stable sense of meaning.15 Religion, therefore, is not a mere psychological illusion to be overcome by reason, but a fundamental discourse that structures reality itself.

This structural understanding reframes the act of conversion. For Freud, a religious conversion might be seen as the substitution of one neurotic symptom for another.4 For Lacan, it represents a far more radical event: a fundamental restructuring of the subject’s relationship to the Symbolic order. It is a change in the very coordinates of one’s reality, desire, and being—a symbolic death and rebirth under a new master signifier.16

The evolution from Freud to Lacan is thus a critical move from analyzing the content of belief to analyzing the structure of belief itself. Freud asks, “What infantile wish does the belief in God fulfill?”.5 Lacan asks, “What structural function does the discourse of God serve in the subject’s psychic economy and the constitution of reality?”.15 This shift is paramount, for it allows an understanding of how a phenomenon like “loose conversion” is not merely a social problem but a structural threat capable of destabilizing a collective symbolic edifice.

| Feature | Freudian Perspective | Lacanian Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Religion | A universal obsessional neurosis; a wish-fulfilling illusion 2 | A master discourse within the Symbolic order 15 |

| Function of God | A projected, exalted father figure for psychic protection 2 | A master signifier (Name-of-the-Father) that guarantees the Symbolic order 13 |

| Source of Belief | Infantile helplessness and the Oedipus complex 2 | The necessity of structuring reality and managing the trauma of the Real 17 |

| View of Ritual | Repetitive actions to manage unconscious guilt and anxiety 2 | Practices that reinforce and stabilize the Symbolic order 14 |

| Pathological Status | A developmental stage to be overcome by science and reason 2 | A necessary structure for subjectivity; its foreclosure leads to psychosis 15 |

Part II: The Hubris of the Convert: A Psychoanalytic Reading of Gerut

Applying this psychoanalytic framework to the individual, the desire for conversion (gerut) emerges as a profoundly complex act, driven by unconscious motivations that belie the convert’s conscious spiritual narrative. It can be read as an act of supreme hubris, an attempt to master one’s own contingency by retroactively correcting a perceived flaw in the divine order.

“G_d Made an Error”: Conversion as Narcissistic Rectification

The impetus for conversion often arises from what psychologists term an “existential impasse or crisis” 20, a moment when the subject confronts a profound sense of lack or meaninglessness. From a psychoanalytic perspective, this is the subject’s encounter with their own constitutive incompleteness. Unable to tolerate this internal void, the subject may employ a powerful defense mechanism: projecting the lack outward. The internal, unbearable truth, “There is something lacking in me,” is transformed into an external, contingent complaint: “God made an error in not making me a Jew.”

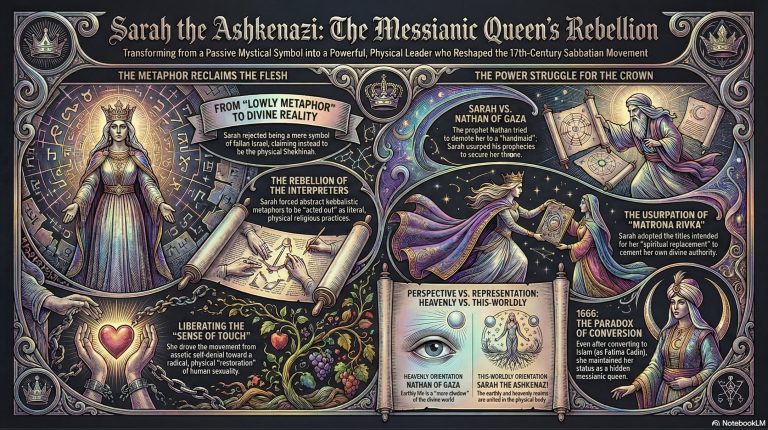

Conversion thus becomes a project of narcissistic rectification. It is a hubristic attempt by the ego to achieve mastery over its own origins, to “cure” the perceived mistake of the Divine Other and retroactively author a new identity.1 This is an archetypal Imaginary fantasy—the dream of attaining a state of wholeness and completeness by identifying with a new, idealized image of the self as a member of the chosen people. This interpretation is deepened by the psychoanalytic view of conversion as a “cover story”.21 As the analyst Adam Phillips suggests, the act of conversion replaces one set of gestures with another, but the original identity is not erased; it is merely repressed, remaining active within the unconscious.21 The fantasy of a total rebirth is therefore structurally impossible; the convert’s past remains as an indelible trace, rendering the new identity inherently unstable.

Theological Counterpoints: Humility, Otherness, and the “Righteous Gentile”

This psychoanalytic reading of hubris finds a striking counterpoint in Jewish theological traditions that explicitly valorize humility (anava) as the ideal spiritual posture. Maimonides, for instance, defines true humility as the “middle path between arrogance and self-abasement,” a secure sense of self-worth rooted not in personal achievement but in divine love.1 The biblical warning, “Be not righteous overmuch” (Ecclesiastes 7:16), can be interpreted as a direct caution against the kind of spiritual perfectionism that might fuel a hubristic desire for conversion.1

Furthermore, traditional Jewish theology obviates the necessity of conversion for spiritual fulfillment. The belief that “the righteous of all nations have a share in the world to come” 22 and the existence of the Noahide covenant as a complete spiritual path for non-Jews 23 renders the intense desire to become a Jew a psychologically curious phenomenon. If salvation does not depend on it, the drive to convert appears less as a theological necessity and more as a personal, psychic exigency. The traditional rabbinic practice of discouraging potential converts can thus be seen as a diagnostic tool—a test designed to probe the nature of the candidate’s desire and filter out motivations grounded in narcissism rather than sincere submission.25

The convert’s desire can be formulated in more advanced Lacanian terms as a fantasy of suturing the lack in the big Other. The subject perceives a lack in their own being and fantasizes that Judaism represents a complete, non-lacking Symbolic order, guaranteed by God. The “error” of their birth is seen as a flaw in this divine system. By converting, the subject fantasizes that they can not only complete themselves but also complete the Other, making the system whole and perfect. This is the apex of hubris: the ambition not merely to fix oneself, but to fix the very structure of reality. This fantasy inevitably confronts a harsh truth upon entry into the Jewish collective.

The Soul of the Ger: Acquiring the “Jewish Baggage”

The Chabad perspective offers a compelling theological metaphor for this psychoanalytic process: upon conversion, the individual receives not only a “Jewish soul” but also the “Jewish baggage”—an innate, internal resistance that makes the spiritual life a constant struggle.25 In Lacanian terms, this “baggage” is nothing other than the subject’s entry into a new, specific Symbolic order. To become a Jewish subject is to become alienated within the particular network of signifiers that constitute Jewish history, law, and identity. The “counter-energy” described by Chabad is the manifestation of the constitutive lack at the heart of this new Symbolic order. The convert, who sought to fill their original void, instead acquires a new, highly structured form of it. The Imaginary fantasy of wholeness is shattered upon the Real of entry into the Law (halakha). This creates a profound paradox of sincerity. Jewish law rightly places immense value on the sincerity of the convert’s intention to accept the commandments.26 Yet, from a psychoanalytic standpoint, the most fervent and “sincere” conscious desire to submit to the “yoke of the commandments” (Kabbalat Ol Mitzvot) 28 may be a screen for the deepest unconscious, narcissistic drive for total mastery and perfection. This complicates the task of any rabbinic court (beit din), as the “real” motivation for conversion is, by definition, inaccessible to the subject themselves.

Part III: Klal Yisrael and the Threat of the Imaginary

The individual psychic drama of the convert has profound implications when magnified to the level of the collective. The contemporary controversy over conversion standards is not merely a political or denominational dispute; it is a symptom of a structural crisis within Klal Yisrael, signaling a dangerous regression from the stability of the Symbolic order to the rivalrous instability of the Imaginary.

Klal Yisrael as a Symbolic Edifice

Klal Yisrael is best understood not as a race or a simple religious affiliation, but as a collective subject constituted and sustained by a unique Symbolic order. This order is the “unfractured totality of Jewish existence” 29, a complex web of shared signifiers that includes the Torah, collective historical memory, and, most critically, the covenant (brit).30 The central organizing principle of this edifice—its master signifier—is halakha. Jewish law provides the “daily, even hourly, marching orders” that structure the life of the observant and, just as importantly, provides the fundamental framework to which even non-observant Jews relate, thereby ensuring a baseline of collective coherence and continuity.33 It is the shared acceptance of this transcendent legal structure that has historically unified the Jewish people across diaspora and diversity.

The Fracturing of the Symbolic: Denominational Conflict and the Crisis of Recognition

The modern, acrimonious “Who is a Jew?” debate, which centers on the legitimacy of conversions performed by different Jewish movements, is a clear symptom of the breakdown of halakha as a universally accepted master signifier.34 When Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform rabbinates issue competing “Certificates of Conversion” (Shtar Geirut) based on radically different criteria, the very definition of the collective becomes unstable.36 This fracturing of the Symbolic leads directly to what commentators describe as “social and religious chaos” 37 and a “painful rift” within the Jewish world, especially concerning matters of personal status such as marriage and lineage.38 The integrity of the peoplehood is existentially threatened when one part of the collective can no longer recognize another as belonging to the same symbolic universe.

The push for more lenient or “loose” conversion standards can be understood as the “return of the repressed” on a collective scale. The strictures of traditional halakha function as a repressive mechanism, maintaining the boundaries and integrity of the collective by excluding that which does not conform. The modern pressure for greater inclusivity, often driven by the reality of intermarriage, represents the eruption of what the Law was designed to contain.35 The “chaos” feared by traditionalists is the eruption of the Real—the messy, uncodified reality of human relationships and desires—that threatens to overwhelm the Symbolic structure. The fierce opposition of ultra-Orthodox parties to non-Orthodox conversions is, from this perspective, a desperate defense against the perceived collapse of the entire Symbolic order under the weight of the Real.40

The Rise of the Imaginary

As the authority of the Symbolic Law wanes, the basis for Jewish unity inevitably shifts. It ceases to be a matter of shared submission to a transcendent, third-person structure (halakha) and becomes a demand for mutual, dyadic recognition between competing groups. The question is no longer “Do we adhere to the Law?” but “Do you recognize me and my converts?” This is a fundamental regression from the Symbolic to the Imaginary order.

In the Imaginary, identity is constituted through mirroring and rivalry. The Reform movement demands its reflection be validated by the Orthodox; the Orthodox movement defines itself in opposition to the perceived illegitimacy of the non-Orthodox movements. This is the logic of Lacan’s mirror stage applied to group dynamics: identity becomes precariously dependent on the image reflected by the other, a dynamic that is inherently unstable and generative of aggression and jealousy. The debate devolves into the binary logic of “who is in, and who is out” 41, a hallmark of Imaginary thinking. This creates a paradox of unity: the very call for Klal Yisrael used by non-Orthodox movements to justify mutual recognition 35 is a symptom of the loss of the structural basis for that unity. The incessant demand for “unity” arises precisely when the underlying Symbolic framework is fractured. It is an Imaginary solution—a plea for mutual validation—to a Symbolic problem: the absence of a shared Law.

| Requirement | Orthodox Judaism | Conservative Judaism | Reform Judaism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sponsoring Authority | Orthodox rabbis only; beit din must be composed of observant Orthodox authorities.39 | Conservative rabbis; beit din required.34 | Individual rabbi’s discretion.34 |

| Acceptance of Mitzvot | Full, sincere acceptance of all applicable commandments as binding.35 | Adoption of Jewish practices; halakha is considered normative but open to interpretation.34 | Commitment to Jewish life and learning; mitzvot are not considered binding.34 |

| Brit Milah / Hatafat Dam Brit | Required for males.36 | Required for males.36 | Optional, at rabbi’s discretion.34 |

| Mikveh Immersion | Required for all converts.36 | Required for all converts.34 | Optional, at rabbi’s discretion.34 |

| Motivation for Marriage | Officially discouraged or disallowed, though some leniency exists.35 | Generally accepted as a valid motivation.35 | Generally accepted as a valid motivation.35 |

Part IV: The Mirror of the Nations: Israel’s National Identity and the Gaze of the Other

The internal crisis of Klal Yisrael’s symbolic structure finds its most potent political expression in the external posture of the State of Israel. As the internal cohesion provided by halakha weakens, the national subject becomes increasingly dependent on external sources for its identity, regressing into an Imaginary relationship with the “mirror of the nations” and performing for the Gaze of the Other.

The National Ego and the Mirror Stage

Political Zionism can be analyzed as a movement born from the collective trauma of centuries of persecution, powerlessness, and shame in the diaspora.44 The creation of the state was, in psychoanalytic terms, a monumental effort to construct a collective “ego”—a strong, sovereign, and unified national subject capable of acting in history, in stark contrast to the historical image of the passive, diasporic Jew.

This process is analogous to Lacan’s mirror stage, the moment when an infant first misrecognizes its fragmented, uncoordinated body in the mirror as a unified, whole image.46 The nation-state of Israel similarly constructed an “Ideal-I” for itself: an idealized image of a heroic, self-reliant, and normalized entity, “a nation like any other.” This image is an Imaginary formation, a necessary “misrecognition” that provides a sense of coherence and mastery but simultaneously papers over the underlying realities of historical trauma, internal fragmentation, and unresolved conflict.48 Susan Sontag’s 1974 film Promised Lands documented this very phenomenon, capturing the “fallacy of the heroic Israeli state” by juxtaposing its idealized self-image with the raw psychic trauma of its citizens.48

Seeking a Reflection in the Other

A subject whose identity is grounded in a stable Symbolic order has less need for external validation. However, as the internal Symbolic cohesion of Klal Yisrael erodes (as argued in Part III), the Israeli national ego becomes pathologically dependent on external mirroring. It requires the “mirror of the nations” to reflect back its cherished “Ideal-I.” This positions Israel in a state of perpetual performance for what Lacan calls the Gaze—an omnipresent, external point from which the subject feels itself being watched and judged.50

The locus of national identity consequently shifts. The defining question moves from an internal, Symbolic one (“Are we, as a people, adhering to our covenant?”) to an external, Imaginary one (“How do they see us? Do they recognize our legitimacy?”). This explains the profound national anxiety surrounding international opinion, United Nations resolutions, media portrayals, and academic boycotts. A critical Gaze from the Other is experienced not as mere political disagreement but as an existential threat to the nation’s very being, because its Imaginary identity is so fragile and dependent on that external reflection.52 In a profound sense, the Gaze of the Other has, in the political sphere, replaced the Law from Sinai as the organizing principle of the collective. The relationship has shifted from a Symbolic one defined by obligation to a transcendent, invisible God, to a scopic one defined by appearance before an immanent, visible “international community.”

The Symptom and Jouissance of National Identity

From a Lacanian perspective, the State of Israel can be analyzed as the “symptom” of the Jewish people. The symptom is the point at which the repressed truth of a subject—its internal contradictions and foundational traumas—erupts into the Real in a coded, repetitive form.54 The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, in this reading, is the endless, traumatic repetition of this symptom, a concrete manifestation of the unresolved historical traumas of both peoples.

The enduring, passionate, and often self-destructive attachment to this national identity, despite its immense costs, can be explained by the concept of jouissance. Jouissance is a paradoxical, excessive, and often painful form of enjoyment that lies beyond the pleasure principle.55 The Israeli “siege mentality,” while consciously lamented, provides a perverse jouissance that organizes and stabilizes the national identity. There is a painful enjoyment derived from being the constant object of the world’s Gaze, even—or perhaps especially—when that Gaze is hostile. This fixation provides the national narrative with its force, its cohesion, and its enduring, tragic appeal.56 The nation’s posture thus represents a collective inversion of the individual convert’s hubris. While the convert seeks to join a perceived-as-whole Symbolic order to cure their own lack, the nation, having lost its sense of that internal wholeness, turns outward and demands that the Other reflect back an image of it as whole. Both are narcissistic strategies, driven by an inability to accept a fundamental, constitutive lack.

Conclusion: The Unstable Covenant

This report has traced a psychoanalytic trajectory from the individual desire for conversion to the collective political posture of a nation-state. The analysis posits that the desire for gerut can be understood as a form of hubris—a narcissistic attempt to correct a perceived “error” in the divine plan and achieve a state of imagined wholeness. This individual psychic drama serves as a microcosm for a larger crisis within Klal Yisrael. The fracturing of halakha as a shared master signifier, a process exacerbated and made manifest by the fierce contemporary debates over “loose” conversion standards, signals the erosion of the Symbolic order that has historically guaranteed Jewish collective identity.

As this internal structure weakens, the collective subject regresses toward the Imaginary order, replacing the stability of the Law with the volatile dynamics of mutual recognition and rivalry. This internal decay is projected outward onto the political stage. The State of Israel, as the political ego of the Jewish people, becomes increasingly dependent on the “mirror of the nations,” seeking external validation for an “Ideal-I” it can no longer ground internally. Its identity becomes precarious, defined not by a covenant with a transcendent Other but by a desperate performance for the Gaze of an immanent other.

The ultimate tragedy, from a psychoanalytic perspective, lies in the impossibility of the project shared by both the hubristic convert and the narcissistic nation: the fantasy of achieving a state of completion, of suturing the fundamental lack that is constitutive of the subject. This is a truth that resonates within Jewish theology itself, with its narratives of flawed patriarchs, a rebellious people, and a history of exile and incompletion. The threat identified in the initial query is therefore not merely a sociological or political problem. It is a profound crisis of the Jewish subject’s relationship with its own foundational Symbolic order. The covenant has become unstable, not only with God, but with the very signifiers that have historically guaranteed the continuity and coherence of the Jewish people.

Works cited

- The Blogs: Humility or Hubris? On Jewish Self-Belief | Bryan …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/humility-or-hubris-on-jewish-self-belief/

- Sigmund Freud’s views on religion – Wikipedia, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigmund_Freud%27s_views_on_religion

- Extract – Freud on Religious Experience as Neurosis – Philosophical Investigations – PEPED, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://peped.org/philosophicalinvestigations/extract-freud-on-religious-experience-as-neurosis/

- WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM FREUD’S … – Lacan in Ireland, accessed on October 15, 2025, http://www.lacaninireland.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/WHAT-CAN-WE-LEARN-FROM-FREUD.pdf

- Psychoanalysis and Religion: Freud, Jung, Kristeva – Freud Museum London, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.freud.org.uk/event/freud-and-religion-freud-jung-kristeva/

- Sigmund Freud: Religion | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://iep.utm.edu/freud-r/

- Freud and Chasidism: Redeeming the Jewish Soul of Psychoanalysis – New Kabbalah, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://newkabbalah.com/kabbalah-and-psychology/jewish-review-freud-and-chasidim-redeeming-the-jewish-soul-of-psychoanalysis/

- Jewishness and psychoanalysis – the relationship to identity, trauma …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://archive.jpr.org.uk/download?id=4314

- Social Theory: Jacques Lacan – (SEPAD) project, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.sepad.org.uk/announcement/social-theory-jacques-lacan

- The Imaginary and Symbolic of Jacques Lacan – DOCS@RWU, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://docs.rwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044\&context=saahp_fp

- The following is a brief discussion of Lacan’s three “Orders”. The text is taken from An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, Dylan Evans, London: Routledge, 1996. – Timothy R. Quigley, accessed on October 15, 2025, http://timothyquigley.net/vcs/lacan-orders.pdf

- Explain in simple terms? Lacan’s Imaginary, Symbolic and Real : r/askphilosophy – Reddit, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/askphilosophy/comments/31p3xx/explain_in_simple_terms_lacans_imaginary_symbolic/

- Is the true formula for atheism the Lacanian declaration (also noted by the Žižekian formula of ideology), “God is unconscious” rather than “God is dead”? : r/psychoanalysis – Reddit, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/psychoanalysis/comments/c3s3bv/is_the_true_formula_for_atheism_the_lacanian/

- Metaphysics Rationalized: Reconfirming the Law Socially Through Religious and Psychoanalytic Interpretations Zairis G. Antonios1 – Transformative Studies Institute, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://transformativestudies.org/wp-content/uploads/Metaphysics-Rationalized-Reconfirming-the-Law-Socially-Through-Religious-and-Psychoanalytic-Interpretations.pdf

- Towards a Lacanian Theology of Religion | New Blackfriars …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/new-blackfriars/article/towards-a-lacanian-theology-of-religion/245A6B2F22A32B82FC5C3AE4525198A0

- Function(s) of religion in the contemporary world: psychoanalytic perspectives : about new types of religious conversions – PubMed, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23412649/

- Religious Conversion and Identity: The Semiotic Analysis of Texts …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282879877_Religious_Conversion_and_Identity_The_Semiotic_Analysis_of_Texts

- Jacques Lacan – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/lacan/

- Full text of “Freud’s view of religion” – Internet Archive, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://archive.org/stream/freudsviewofreli00deab/freudsviewofreli00deab_djvu.txt

- A Leap of Faith. What is Conversion? A Psychologist’s Perspective, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://dsc.duq.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010\&context=spiritan-horizons

- Adam Phillips book and conversion therapy. : r/psychoanalysis – Reddit, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/psychoanalysis/comments/1ds1uc3/adam_phillips_book_and_conversion_therapy/

- Why doesn’t Judaism promote conversion, whereas other faiths do …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.jewishboston.com/read/why-doesnt-judaism-promote-conversion-whereas-other-faiths-do/

- Why don’t Jews try to convert non-Jews? – Root Source, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://root-source.com/ask-the-rabbi/why-dont-jews-try-to-convert-non-jews/

- Stranger – Ger – St Andrews Encyclopaedia of Theology, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.saet.ac.uk/Judaism/StrangerGer

- Why Do Rabbis Discourage Conversions? – Chabad.org, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/248165/jewish/Why-Do-Rabbis-Discourage-Conversions.htm

- Conversion of a Person Suffering from Mental Illness Archives …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.ccarnet.org/responsa-topics/conversion-of-a-person-suffering-from-mental-illness/

- Gerut – (Intro to Judaism) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations | Fiveable …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-to-judaism/gerut

- Glossary of Jewish Terms – Congregation Anshai Emeth, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.anshaiemeth.org/get-involved/welcome-judaism/glossary-jewish-terms/

- The Sacred Cluster – Jewish Theological Seminary, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.jtsa.edu/torah/the-sacred-cluster/

- Sharing the Secret to Jewish Unity – Chabad.org, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/theJewishWoman/article_cdo/aid/4215023/jewish/Sharing-the-Secret-to-Jewish-Unity.htm

- Klal Yisrael – (Intro to Judaism) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations | Fiveable, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-to-judaism/klal-yisrael

- Why Is Conversion to Judaism So Hard? – Chabad.org, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/3002/jewish/Why-Is-Conversion-to-Judaism-So-Hard.htm

- How Do the Issues in the Conversion

Controversy Relate to …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://dje.jcpa.org/articles2/conversion.htm - 15.2 Conversion to Judaism: Process and Controversies – Fiveable, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://fiveable.me/introduction-to-judaism/unit-15/conversion-judaism-process-controversies/study-guide/lNltW9tyRWfk9Dg2

- Contemporary Issues in Conversion | My Jewish Learning, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/contemporary-issues-in-conversion/

- Conversion to Judaism – Wikipedia, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conversion_to_Judaism

- The Supreme Court Decision on Conversions in Israel: Threat or …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://utj.org/viewpoints/2021/03/the-supreme-court-decision-on-conversions-in-israel-threat-or-opportunity-for-halakhic-judaism/

- Threat to Reform Rights in Israel | Union for Reform Judaism, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://urj.org/what-we-believe/resolutions/threat-reform-rights-israel

- Denominational Differences On Conversion – My Jewish Learning, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/cross-denominational-differences-regarding-conversion/

- Ultra-Orthodox threaten to bolt government if conversion bill …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.timesofisrael.com/ultra-orthodox-threaten-to-bolt-goverment-if-conversion-bill-endangered/

- Klal Yisrael: Moving Beyond Binary Descriptions – Jim Joseph Foundation, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://jimjosephfoundation.org/news-blogs/klal-yisrael-moving-beyond-binary-descriptions/

- Klal Yisrael: Moving beyond binary descriptions – eJewishPhilanthropy, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://ejewishphilanthropy.com/klal-yisrael-moving-beyond-binary-descriptions/

- Another Halakhic Approach to Conversions | jewishideas.org, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.jewishideas.org/article/another-halakhic-approach-conversions

- The Question of Zion – Dissent Magazine, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.dissentmagazine.org/wp-content/files_mf/1389732584d6Lappin.pdf

- The Political Unconscious – Jewish Currents, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://jewishcurrents.org/the-political-unconscious

- Identity Construction and The Mirror Stage – Syracuse University Art …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://museum.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Identity-Construction-and-the-Mirror-Stage.pdf

- Lacan’s Concept of Mirror Stage – Literary Theory and Criticism, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://literariness.org/2016/04/22/lacans-concept-of-mirror-stage/

- Grappling with Israel: From Sontag to Lacan and the … – Jadaliyya, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/26998

- Lacanian Psychoanalysis: The Mirror Stage and the Wound of Split Subjectivity |, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://iambobbyy.com/2019/08/04/lacanian-psychoanalysis-the-mirror-stage-and-the-wound-of-split-subjectivity/

- International misrecognition: The politics of humour and national, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://scispace.com/pdf/international-misrecognition-the-politics-of-humour-and-57pblpw78t.pdf

- Lacan on Gaze – International Journal of Humanities and Social …, accessed on October 15, 2025, http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_5_No_10_1_October_2015/15.pdf

- Deciphering the Gaze in Lacan’s ‘Of the Gaze as Objet Petit | The DS …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://thedsproject.com/portfolio/deciphering-the-gaze-in-lacans-of-the-gaze-as-objet-petit-a/

- “White Zombie (1932) and the lacanian gaze | by Psychotic’s guide to memes | Medium, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://medium.com/@akineo/white-zombie-1932-and-the-lacanian-gaze-33c252b573ab

- Lacanian psychoanalysis has a tense relationship with political – International Journal of Zizek Studies, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://zizekstudies.org/index.php/IJZS/article/download/75/72

- I Can’t Get No Enjoyment Lacanian Theory and The Analysis of …, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/531551265/I-Can-t-Get-No-Enjoyment-Lacanian-Theory-and-the-Analysis-of-Nationalism

- Using Lacanian Psychoanalysis to Explore what is … – Discourse Unit, accessed on October 15, 2025, https://discourseunit.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/arcp7dashtipour.doc