Introduction: Primordial Monsters and the Messianic Feast

In the foundational narratives of Jewish tradition, the world is bounded by monsters. Rabbinic literature describes three primordial beasts, each a guardian presiding over a domain of creation: the great fish Leviathan, ruler of the sea; the colossal land-dweller Behemoth; and the giant bird Ziz, master of the sky.1 These are not simply mythological curiosities; they are figures that encode the foundational antagonism of existence: the divine imposition of order upon a primordial chaos. Leviathan, the twisting sea serpent, and Behemoth, the mighty bull of the land, represent the apex of God’s creation, yet also the ever-present potential for cosmic disruption.1 To ensure the world’s survival, God’s first act was one of limitation: He created a male and female of each, but slew the female Leviathan, preserving her flesh for a future purpose, lest their multiplication destroy the world.3

This future purpose is central to Jewish eschatology. The Talmud and Midrash teach that in the End of Days, upon the advent of the Messiah, the righteous will be gathered for a spectacular banquet. The main course of this feast will be the flesh of these very monsters.2 After a final, climactic battle, Leviathan and Behemoth will be slain, and their bodies will become the sustenance for the redeemed. Their skin will be used to fashion the walls of the sukkah in which the righteous will dine, illuminated by the hide’s brilliant glow.3 This powerful image of consuming the monsters is not merely a promise of reward; it is a profound theological statement about the final state of creation, where that which was once a threat becomes a source of sanctified nourishment and divine revelation.5

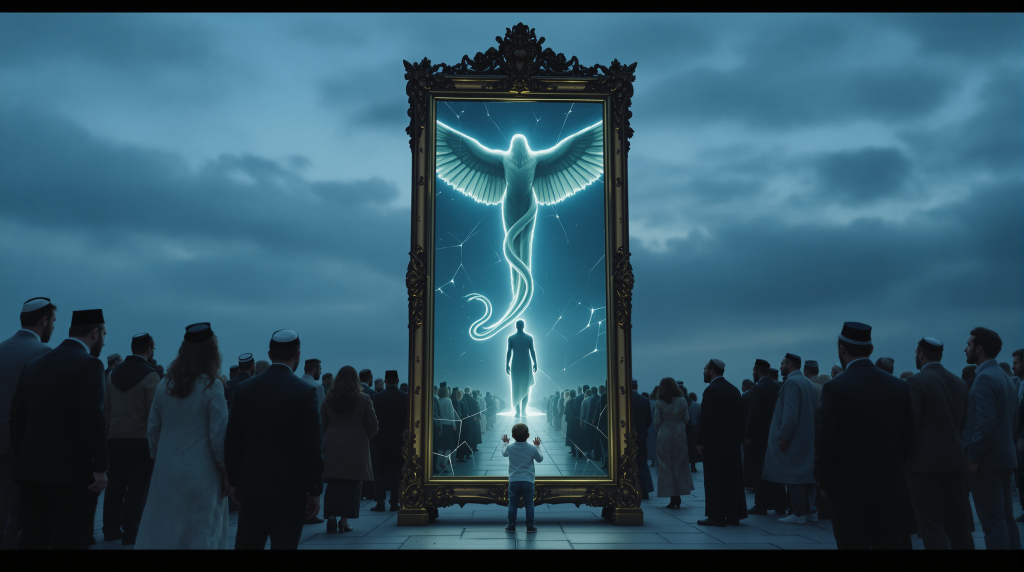

This report proposes a psychoanalytic reading of this theological drama, specifically through the lens of Jacques Lacan, to reveal the deep psychological structures undergirding the Jewish political imagination. The central thesis is that the clamor for a mortal king in the Book of Samuel represents a foundational political trauma: the rejection of God’s abstract, invisible kingship—the ultimate Symbolic Order—in favor of a tangible, human sovereign, an object of Imaginary identification. Consequently, the primordial monsters—Leviathan, Behemoth, and Ziz—can be understood as figurations of the repressed Real: the raw, chaotic, and terrifying domain of collective jouissance—a paradoxical, painful enjoyment—that any political order must contain to cohere.7

From this perspective, the figure of the Messiah (Meshiach) emerges as the ultimate psychoanalytic and political solution. He is the awaited sovereign who will not merely replace the flawed human kings but will institute a perfect and final Symbolic Order. His arrival makes possible the messianic feast, which symbolizes the ultimate “traversing of the fantasy”: the assimilation and sanctified enjoyment of the monstrous Real. The journey of the Jewish people, from the flawed demand for a king to the hope for the Messiah, is thus a spiritual milieu reflecting the struggle with sovereignty, law, and the terrifying, ecstatic forces that lie at the heart of the collective soul.

Part I: The Clamor for a King – Rejecting the Divine “Big Other”

The political history of Israel begins not with a king, but with the rejection of one. The period of the Judges was defined by the principle that God alone was Israel’s sovereign. Yet, this divine kingship proved psychologically untenable. The narrative of 1 Samuel 8, which details the people’s demand for a mortal ruler, is more than a political turning point; it is a profound psychological drama. A Lacanian reading reveals this event as a collective flight from the burden of an abstract and invisible Law toward the comforting illusion of a visible, human authority.

The Unmediated Kingdom: God as the Abstract Sovereign

In the era before the monarchy, God ruled Israel directly, raising up judges in times of crisis.8 This theocracy represents a unique political structure: a kingdom with an invisible King. In Lacanian terms, God functions here as the ultimate “big Other”—the radical alterity of the Symbolic order itself, the impersonal and abstract network of Law (the Torah) that precedes and constitutes the community.9 This “big Other” is the guarantor of meaning, but it offers no image for identification, no tangible body in which the nation can see its own unity reflected. To be ruled by an invisible God is to be subject to a pure, unmediated Law, a Symbolic order without an Imaginary support.

This proves to be an unbearable condition. The catalyst for change is the corruption of the prophet Samuel’s sons, who “turned aside after gain; they took bribes and perverted justice”.11 This failure of human mediation exposes the vulnerability of the existing system. The elders of Israel, faced with Samuel’s old age and his sons’ unsuitability, make a fateful demand: “Now, set up for us a king to judge us like all the nations”.12

The Social Contract as Collective “Mirror Stage”

This demand is a moment of profound political and psychological significance. It is a rejection of Israel’s unique status and a desire for conformity: to be “like all the nations”.14 This can be read as a collective version of Lacan’s “mirror stage.” In the mirror stage, an infant first recognizes its reflection and jubilantly identifies with this coherent, unified image, which provides a fictional sense of wholeness that masks its underlying fragmentation. The nations surrounding Israel, with their visible kings, provided such a mirror. The Israelites desired to see their own national unity and power reflected in the singular, majestic body of a mortal sovereign. They were fleeing the anxiety of an abstract relationship with an invisible God for the comforting, tangible image of a human king.

God’s response to Samuel confirms this interpretation. The demand is not a personal rejection of the prophet, but a theological one: “Listen to the voice of the people… for they have not rejected you, but they have rejected Me from reigning over them”.16 They are rejecting the Symbolic Father in favor of an Imaginary one. They crave a leader who will “go out before us and fight our battles”—a visible agent of power, rather than a divine promise.13

The “Ways of the King”: The Price of the Imaginary

Before granting their request, God commands Samuel to issue a stark warning about the “ways of the king” (1 Samuel 8:11-17). This speech outlines the true cost of their desire. The king will not be a benevolent father but a rapacious master. He will conscript their sons for his army, take their daughters for his court, and seize the best of their fields, vineyards, and olive groves to give to his courtiers.12

This warning can be understood as the psychoanalytic price of installing a human “Name-of-the-Father.” In Lacanian theory, the Name-of-the-Father is the signifier that represents the function of law and prohibition, inserting the subject into the Symbolic Order by imposing a limit on their desires. The Israelite king will perform this function, but as a flawed, human institution. Samuel’s warning details the sacrifice of life, liberty, and property—the raw substance of the people’s existence, their jouissance—that will be required to sustain this new political fantasy. The people, however, are undeterred. They ignore the warning, insisting on their demand.13 They willingly accept this political “castration” in exchange for the security and recognition promised by the image of a king. This fateful choice inaugurates a new political order, one founded on a fundamental rejection, a desire for a worldly master over a divine one.

Part II: A Psychoanalytic Bestiary – Leviathan, Behemoth, Ziz, and the Repressed Real

To fully grasp the psychic forces at play, we must return to the monsters. Within the Jewish spiritual milieu, these primordial entities have a specific eschatological destiny. By mapping the complete Talmudic bestiary onto the Lacanian registers, we can construct a psychoanalytic-political taxonomy that illuminates the deep structures of the Jewish relationship to divine and earthly power, covering the domains of sea, land, and sky.

Table 1: A Psychoanalytic-Midrashic Glossary of the Bestiary

| Figure/Concept | Biblical/Talmudic Origin | Political Interpretation (1 Samuel 8) | Lacanian Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Divine Kingship | God as the direct, invisible King of Israel. | The rejected, abstract form of government. | The Symbolic Order; the “big Other” of pure Law (Torah) without an Imaginary support. |

| Mortal King | The human king demanded by the people to be “like all the nations”.13 | The new, centralized political authority. | The Imaginary sovereign; the object of collective identification (mirror stage); the humanly-instituted Name-of-the-Father. |

| Leviathan | Primordial sea monster; a twisting serpent whose power is mastered only by God.1 | The untamed chaos that necessitates a strong ruler. | The horrifying, chaotic aspect of the Real; the death drive; the threat of dissolution that must be contained. |

| Behemoth | Primordial land monster; a colossal bull representing immense earthly power.1 | The raw, untamed power of the people/land. | The primordial jouissance of the collective body; the traumatic excess of earthly substance excluded by the Symbolic. |

| Ziz | Primordial sky monster; a giant bird whose wingspan can block out the sun. | The overwhelming, omnipresent nature of divine judgment. | The atmospheric Real; the unsymbolizable divine Gaze or Voice; a traumatic, non-substantial presence. |

| Messianic Feast | The eschatological banquet where the righteous will consume the flesh of Leviathan and Behemoth.2 | The ultimate resolution of political and spiritual conflict. | The assimilation of the Real; the sanctified enjoyment of jouissance made possible by the perfect Symbolic Order of the Messiah. |

The Monsters as the Primordial Real

In Talmudic lore, Leviathan, Behemoth, and Ziz are the kings of their respective domains: sea, land, and air. Their existence precedes human political order, and their immense power must be divinely constrained to allow the world to exist.1 In our psychoanalytic bestiary, they represent the Lacanian Real—the unstructured, traumatic void that lies beyond symbolization. They are the raw stuff of creation before it is organized by the divine Word.

Behemoth, the land beast, represents the Real of the social body itself. It is the raw, undifferentiated life-substance of the collective, the seething potentiality before it is carved up by the Law. It is the people’s capacity for jouissance—that excessive, paradoxical, and often painful enjoyment that lies beyond the pleasure principle.39 Leviathan, the chaos monster of the deep, represents a more horrifying aspect of the Real. It is the embodiment of the death drive, the terrifying thrill of transgression and dissolution that threatens to pull all of creation back into the abyss.4 Completing this taxonomy is Ziz, the sky beast. If Behemoth is earthly substance and Leviathan is oceanic chaos, Ziz represents the atmospheric Real. It is not a monster of bodily mass but of overwhelming presence—the traumatic, unsymbolizable divine Gaze or Voice that looks down from above, an observational trauma that cannot be grasped or contained.39

God’s act of slaying the female Leviathan and separating the beasts is the foundational act of the Symbolic—the imposition of a limit that makes a structured reality possible.3 God “plays” with Leviathan, demonstrating that this terrifying force is subordinate to His order.4

Excursus – The Missing Ziz

The Messianic Feast as the Assimilation of Jouissance

The most radical element of the Jewish mythos is the ultimate destiny of these monsters: they are to be eaten.3 This eschatological banquet is a powerful metaphor for the final “traversing of the fantasy.” In the Messianic era, the monstrous Real, the source of primordial terror, is not annihilated but assimilated. The jouissance that had to be repressed is finally integrated and becomes a source of sanctified pleasure for the righteous.

This act of consumption signifies a radical transformation in the subject’s relationship to the Real. The terror is overcome, and the energy of the drive is fully harmonized within a new, perfect Symbolic Order. Commentators like Maimonides interpreted this physical feast as an allegory for the ultimate “spiritual enjoyment of the intellect,” a final and complete apprehension of divine knowledge.2 This aligns perfectly with a Lacanian interpretation: the feast represents the moment when the Real is no longer an unsymbolizable horror but is fully integrated into a new structure of meaning, providing the ultimate satisfaction. It is the promise that at the end of history, we will not just defeat our monsters, but find holy nourishment in them.6

Part III: The Failed Feast: The Monarchy’s Premature Consumption of Jouissance

The political experiment initiated by the demand in 1 Samuel 8 is one of tragic, though necessary, failure. The report does not simply jump from the initial trauma to the final resolution; the intervening history of the monarchy serves as a crucial psychoanalytic bridge. It represents a flawed, unsanctioned attempt by a human political order to manage the monstrous Real—a premature effort to consume the collective jouissance that was destined to fail, thereby demonstrating the necessity of the true Messiah.39

The “ways of the king” foretold by Samuel (1 Samuel 8:11-17) are not merely a list of political abuses but a program for the violent appropriation of the people’s substance. When the king “takes” their sons for his army, their daughters for his court, and the “best of your fields and vineyards and olive orchards,” he is performing an unsanctified political act of consumption. This is an earthly, Imaginary king’s grasping attempt to seize and control the raw being of the nation—its life, its produce, its future. In our psychoanalytic framework, this is the monarchy’s attempt to consume Behemoth prematurely, to master the jouissance of the collective body through force and confiscation rather than divine sanction.39

Because this act lacks the proper Symbolic authorization, it does not lead to a sanctified feast but to trauma, disaster, and ultimately, exile. The history of the monarchy—from Saul’s paranoia to David’s transgressions and Solomon’s excesses—is the history of this failed assimilation. It is a destructive attempt to master the monster of the Real with inadequate earthly power. This historical failure is not a mere political backdrop; it is the concrete proof that only a divinely sanctioned messianic feast can successfully and non-traumatically integrate the Real. The flawed kings demonstrate that without the perfect Symbolic Order, any attempt to consume the monster will only result in the monster consuming the kingdom from within.39

Part IV: The Nature of Meshiach – The Sovereign to Come

The history of the monarchy’s failure sets the stage for the ultimate political hope in Judaism: the coming of the Messiah, the true and final king who can succeed where all mortal predecessors failed.

The Failure of the Imaginary King

The kings of Israel and Judah are Imaginary sovereigns, trapped between the divine Law they are meant to uphold and the human desires and political pressures they face. As demonstrated by their failed attempt to master the nation’s jouissance through political force, the humanly-instituted “Name-of-the-Father” proved unable to fully contain the antagonisms of the social body. This failure ultimately leads to destruction and exile, the traumatic dissolution of the very political order the people so desperately desired. The Imaginary sovereign proves to be an inadequate defense against the irruptions of the Real, whether in the form of internal conflict or external enemies.

The Messiah as the Perfect Symbolic Sovereign

The Jewish concept of the Messiah is the answer to this history of failure. The Messiah is not a divine being, but a perfect human leader—a king, a descendant of David, who will finally realize the ideal of sovereignty.20 His mission is profoundly political: he will gather the Jewish exiles, rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem, restore the Davidic dynasty, and establish a government that will be the center for a world at peace.22

In Lacanian terms, the Messiah is the figure who will institute a perfect Symbolic Order. He is the “subject supposed to know,” the master who can finally unite desire with the Law. His rule is not a rejection of God’s kingship but its ultimate instrument on earth. The Messianic Age represents the fantasy of a “big Other” that is not lacking, a social order without antagonism, where all nations will recognize one God and live in peace.23 Maimonides, in his “deflationary” view of the messianic era, emphasizes its naturalistic character.10 He argues there will be no change in the laws of nature, but rather a political restoration of Jewish sovereignty and a universal turn toward ethical monotheism, as embodied in the Noahide laws.10 This vision is of a perfected Symbolic Order, where the primary occupation of humanity will be the pursuit of the knowledge of God.10

The arrival of this perfect sovereign is the necessary precondition for the messianic feast. It is only under his just and stable rule—the final, unshakeable “Name-of-the-Father”—that the monstrous forces of the Real can be safely approached, assimilated, and transformed into a source of joyous celebration. The King Messiah makes it possible to finally eat the monsters.

Conclusion: Traversing the Political Fantasy

The ancient figures of Leviathan, Behemoth, and Ziz, when read through the lens of Jewish political history and Lacanian psychoanalysis, reveal a timeless spiritual drama. The demand for a king in the Book of Samuel is the story of a people fleeing the anxiety of an abstract, Symbolic God for the deceptive comfort of a tangible, Imaginary ruler. This act establishes a political order whose history is defined by a failed, premature attempt to master the monstrous Real of collective jouissance.

Within this framework, the Talmudic myths of the primordial beasts function as potent symbols of the Real in its various dimensions—earthly, oceanic, and atmospheric. The brilliance of the Jewish eschatological vision lies in its ultimate hope: not the eternal repression of this force, but its final, sanctified consumption. The messianic feast is the promise that the very energies that threaten creation will one day become its most sublime nourishment.

This transformation is predicated on the arrival of the Messiah, the ideal sovereign who will establish a perfect and final Symbolic Order. He resolves the political antagonism that began with the first flawed kings by perfectly aligning human governance with divine Law. The journey from the rejection of God’s kingship, through the traumatic failure of the monarchy, to the yearning for the King Messiah is a collective “traversing of the fantasy.” It is a movement from a politics of Imaginary substitution to a politics of Symbolic fulfillment, a hope that history will culminate not in the annihilation of our deepest, most monstrous energies, but in a holy feast where we can, at last, sit at the table with our fears and find them, to our eternal delight, to be kosher.

Appendix: The Christian Mythos and the Management of Divine Excess

The Christian mythos offers a different psychoanalytic structure for resolving the antagonism between the Symbolic order and the Real. Where the Jewish eschatology culminates in the consumption of the monstrous Real, Christianity centers on the consumption of the divine figure Himself. This shift reveals an alternative strategy for managing jouissance: not the assimilation of a monstrous, earthly excess, but the ritualized management of a divine, transcendent excess.39

The Eucharist: Managing Divine Plenitude

The central ritual of Christianity is the Eucharist, in which the faithful consume bread and wine that have been transubstantiated into the body and blood of Christ.27 This act of incorporation is a stark contrast to the messianic feast.28 Here, the object of consumption is not the monstrous Behemoth but the body of Christ, the Logos made flesh.29 The theological logic, as articulated by thinkers like Aquinas, is that after Christ, there is a “superabundance” of divine truth in the world. The sacrament thus acts as a defense, a way to ensure this “divine plenitude is received in proper proportion,” lest the subject be burned by the intensity of divine love. The Eucharist is a ritualized management of a divine excess, rather than an assimilation of a monstrous one.

The Crucifixion: The Death of the Big Other

The pivotal event of the Christian narrative is the crucifixion, culminating in Christ’s cry of dereliction: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” For thinkers like Slavoj Žižek, this is the moment of divine atheism, the death of God as the transcendent “big Other” who guarantees the Symbolic Order.30 On the cross, the ultimate guarantor of meaning reveals himself to be lacking, exposing the void of the Real at the heart of the Symbolic. Christ’s suffering and death represent the ultimate encounter with the Real in its most traumatic form: abandonment, pain, and the finality of the corpse.32

However, this encounter is immediately reframed not as a failure, but as the very mechanism of salvation. Christianity uses death and suffering—the irruption of the Real—to transcend the Real. By willingly submitting to the ultimate trauma, Christ is said to have exhausted its power. This act posits a radical solution: the horror of the Real is not to be contained by law or assimilated through enjoyment, but to be nullified by a divine figure who takes it entirely upon himself.

The Resurrected Christ as Sinthome

The resurrected Christ is a paradoxical figure who functions as a fusion of the three Lacanian registers. He is an Imaginary figure, appearing as a recognizable, idealized image to his followers.34 He is a Symbolic figure, the Word made flesh, the master signifier who anchors the new universal community of the Holy Spirit.32 And he is a figure of the Real, a body that has passed through the impossible trauma of death and returned.29

It is this impossible fusion that allows the figure of Christ to function as what Lacan, in his later work, termed the sinthome. The sinthome is a fourth ring that knots together the Real, Symbolic, and Imaginary, providing consistency to the subject in the absence of a fully functioning paternal metaphor.37 The death of God the Father on the cross creates a void in the Symbolic that requires a new knot to hold reality together. The resurrected Christ becomes this universal sinthome, a singular point of identification that sutures the subject’s world.38 This represents an alternative mode of “traversing the fantasy.” Rather than a collective assimilation of the monstrous Real, it offers an identification with a divine figure who has already processed the trauma of the Real. It reorients the subject’s relationship to enjoyment, focusing it not on the earthly but on the transcendent, presenting a different, yet equally profound, mechanism for confronting the excesses that structure human existence.39

Bibliography of Works Cited

- The Three Jewish Monsters Charged With Saving the World, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://blog.nli.org.il/en/three_jewish_monsters/

- LEVIATHAN AND BEHEMOTH – JewishEncyclopedia.com, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/9841-leviathan-and-behemoth

- Leviathan – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leviathan

- Leviathan | Texts & Source Sheets from Torah, Talmud and Sefaria’s library of Jewish sources., accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.sefaria.org/topics/leviathan

- eschatological consumption of – leviathan and behemoth as revelation of the messianic torah – Marquette University, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.marquette.edu/maqom/leviathantorah.pdf

- 36 Days of Judaic Myth: Day 35, The Feast at the End of Days – Matthew Kressel, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.matthewkressel.net/2015/10/12/36-days-of-judaic-myth-day-35-the-feast-at-the-end-of-days/

- Lacan and Monotheism: Psychoanalysis and the Traversal of Cultural Fantasy, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://legacy.chass.ncsu.edu/jouvert/v3i12/reinha.htm

- 1 Samuel 8 Commentary – Precept Austin, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.preceptaustin.org/1-samuel-8-commentary

- Chapter 2 Leviathan and Behemoth in Second Temple Judaism – Brill, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://brill.com/previewpdf/book/edcoll/9789004369931/B9789004369931-s003.xml

- Maimonides on the Messianic Era: The Grand Finale of Olam Ke-Minhago Noheg – Hakirah, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://hakirah.org/Vol32Diamond.pdf

- 1 Samuel 8 – Coffman’s Commentaries on the Bible – StudyLight.org, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.studylight.org/commentaries/eng/bcc/1-samuel-8.html

- Shmuel I – I Samuel – Chapter 8 – Tanakh Online – Torah – Bible, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/15837/jewish/Chapter-8.htm

- 1 Samuel 8:4-20 – Israel Demands a King – Enter the Bible, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://enterthebible.org/passage/1-samuel-84-20-israel-demands-a-king

- www.theologyofwork.org, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.theologyofwork.org/old-testament/samuel-kings-chronicles-and-work/from-tribal-confederation-to-monarchy-1-samuel/the-israelites-ask-for-a-king-1-samuel-84-22/#:~:text=Samuel%20warns%20the%20people%20that%20kings%20lay%20heavy%20burdens%20on%20a%20nation.\&text=In%20fact%2C%20the%20kings%20would,of%20God%20himself%2C%20as%20king.

- Israel’s Demand for a King – She Reads Truth, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://shereadstruth.com/israels-demand-for-a-king/

- The Israelites Ask For a King (1 Samuel 8:4-22) | Theology of Work, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.theologyofwork.org/old-testament/samuel-kings-chronicles-and-work/from-tribal-confederation-to-monarchy-1-samuel/the-israelites-ask-for-a-king-1-samuel-84-22/

- 1 Samuel 8 – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1_Samuel_8

- Why did the Israelites ask for a king and want the same form of political rule as other populations? – Reddit, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/AcademicBiblical/comments/qjsnsm/why_did_the_israelites_ask_for_a_king_and_want/

- What are the Leviathan, Behemoth, and the Ziz? : r/Judaism – Reddit, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Judaism/comments/1vza4h/what_are_the_leviathan_behemoth_and_the_ziz/

- Messiah – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messiah

- How do the Jewish expectations of the Messiah as a powerful ruler conflict with the Christian portrayal of Jesus? – Quora, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.quora.com/How-do-the-Jewish-expectations-of-the-Messiah-as-a-powerful-ruler-conflict-with-the-Christian-portrayal-of-Jesus

- Mashiach: The Messiah – Judaism 101 (JewFAQ), accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.jewfaq.org/mashiach

- Messiah in Judaism – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messiah_in_Judaism

- What Is the Jewish Belief About Moshiach (Messiah)? – Chabad.org, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/108400/jewish/The-End-of-Days.htm

- Maimonides – Laws Pertaining to The Messiah – Jews for Judaism, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://jewsforjudaism.org/knowledge/articles/maimonides-laws-pertaining-messiah

- Maimonides’ Idea of the Messianic Age – San Diego Jewish World, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.sdjewishworld.com/2024/05/14/maimonides-idea-of-the-messianic-age/

- Eucharistic miracle – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eucharistic_miracle

- Newsletter – Lacan dot com, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.lacan.com/newsletterJLWa.html

- Lacanian Psychoanalysis and the Traumatic Intervention of the Eucharist: An Interview with Marcus Pound – The Other Journal, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://theotherjournal.com/2008/01/lacanian-psychoanalysis-and-the-traumatic-intervention-of-the-eucharist-an-interview-with-marcus-pound/

- From psychoanalysis to metamorphosis | 3 | The Lacanian limits of Žiže – Taylor & Francis eBooks, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315102900-3/psychoanalysis-metamorphosis-brian-becker

- Žižek, Peterson, and the Christian Atheist – Pastor Writer, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://pastorwriter.com/zizek-peterson-and-the-christian-atheist/

- Other Voices 1.3 (January 1999), Jürgen Braungardt, “Theology After Lacan: A Psychoanalytic Approach to Theological Discourse”, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.othervoices.org/1.3/jbraungardt/theology.php

- Žižek Has a Lot to Say About Christ, but Should the Church Listen?, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/zizek-has-a-lot-to-say-about-christ-but-should-the-church-listen/

- The Imaginary and Symbolic of Jacques Lacan – DOCS@RWU, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://docs.rwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044\&context=saahp_fp

- Explain in simple terms? Lacan’s Imaginary, Symbolic and Real : r/askphilosophy – Reddit, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/askphilosophy/comments/31p3xx/explain_in_simple_terms_lacans_imaginary_symbolic/

- LACANIAN PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PSYCHOLOGY OF RELIGION By Hercules Karampatos, MA, Cand. Ph.D. Abstract This is a study, at the core, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://epub.lib.uoa.gr/index.php/theophany/article/download/2376/2028

- Sinthome – Wikipedia, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sinthome

- Mirrors/ Lacan with Joyce/ Theory, Psychoanalysis, and Literature – Breac, accessed on October 14, 2025, https://breac.nd.edu/articles/mirrors-lacan-with-joyce-theory-psychoanalysis-and-literature/

- Lacan,_Leviathan,_and_the_Missing_Sky_Monster__Reframing_Jewish-transcription-202510140535.pdf