I. Introduction: The Traumatic Real and the Forging of the Rabbinic Subject

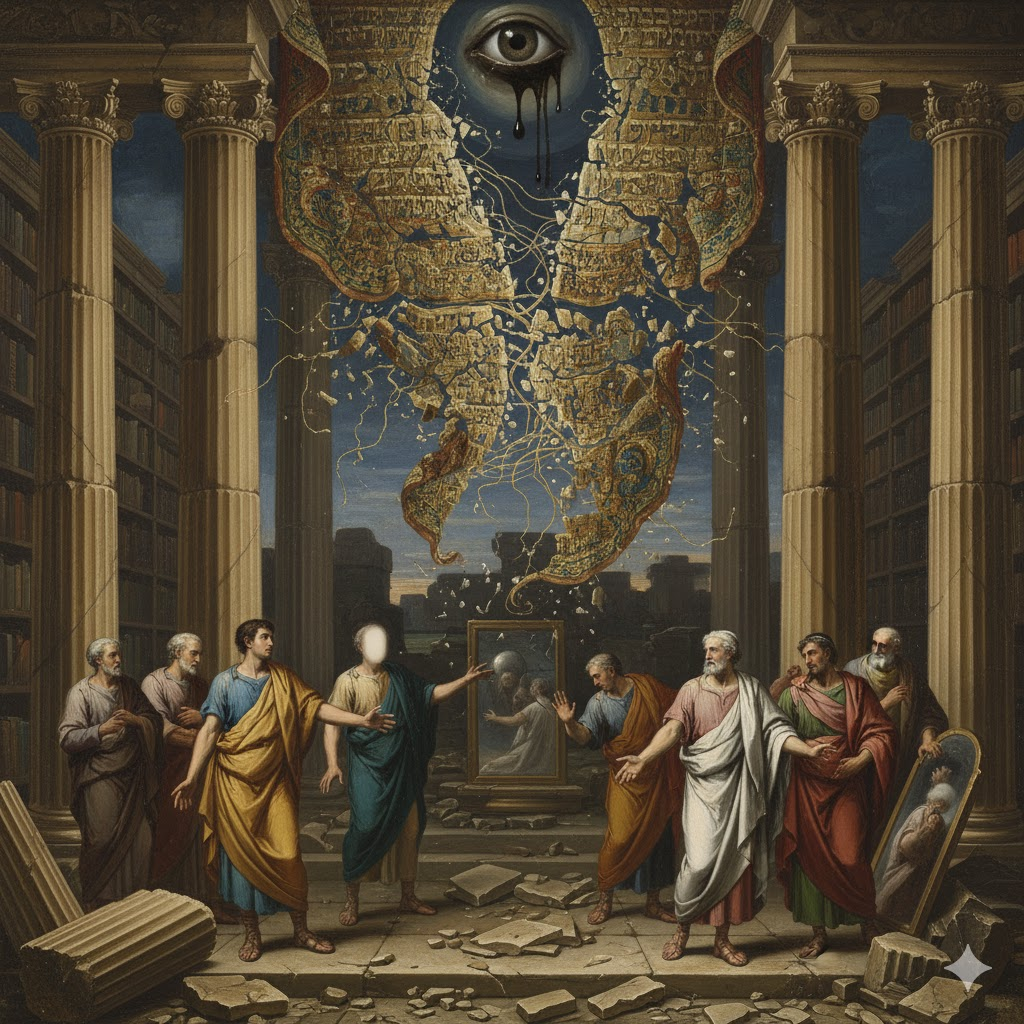

The destruction of the Second Temple by Roman legions in 70 CE was an event of such magnitude that it cannot be understood merely as a political or military catastrophe. For the Jewish people, it was a profound psychic rupture, a collective trauma that dismantled the very coordinates of their symbolic universe.1 This report will argue that the Talmudic narrative of Rabbi Akiva and Rachel, the daughter of Ben Kalba Savua, functions as a foundational suture for the new form of subjectivity that arose from this trauma: the rabbinic subject. Employing the dual methodologies of psychohistory and Lacanian psychoanalysis, this analysis will posit the destruction of the Temple as an encounter with the Lacanian Real—the raw, unsymbolizable void of absolute loss—and the subsequent emergence of Rabbinic Judaism as a monumental effort to repair this void with a new Symbolic order grounded in language and law. The story of Akiva, in this reading, is not a historical biography but a structuring fantasy, a narrative that stages the painful but ultimately triumphant birth of the ideal rabbinic subject from a state of primordial lack, through a process of radical alienation in the Symbolic order of Torah.

A Deep dive from Google NotebookLM

The Rupture of the Symbolic

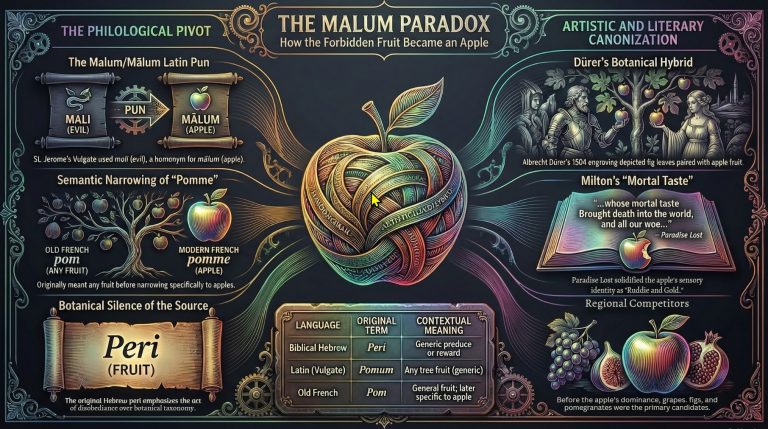

In the psychoanalytic framework of Jacques Lacan, the Symbolic order is the realm of language, law, and social structures that constitutes reality for the subject.3 It is a network of signifiers that pre-exists the individual and into which the individual must be inserted to become a speaking being. This order is anchored by certain master signifiers, or points de capiton (“quilting points”), which retroactively fix meaning and provide a sense of coherence and stability. Before 70 CE, the Jerusalem Temple was arguably the ultimate point de capiton for Judaism. It was not merely a building but the central signifier that organized and guaranteed the entire symbolic economy of Jewish life. It was the physical locus of the divine presence, the axis of the covenant between God and Israel, and the sole site for the sacrificial rites that managed sin, purity, and atonement.2 The Temple’s existence underwrote the authority of the priesthood, the calendar of festivals, and the very identity of the nation.

Its destruction, therefore, was a traumatic loss that went far beyond the physical. It was the erasure of the master signifier, an event that caused the entire symbolic network to unravel. The loss of the Temple was an encounter with what Lacan terms the Real: the domain of that which resists symbolization, the traumatic kernel that cannot be integrated into the fabric of reality.5 The devastation, famine, and mass enslavement described by contemporaries were the tangible manifestations of this encounter, but the deeper trauma was the collapse of meaning itself.2 The covenant appeared broken, God’s promise voided. This precipitated a collective crisis, a confrontation with a gaping hole in the place of the “big Other”—Lacan’s term for the symbolic locus of law and truth, the guarantor of the covenant.8 The central question that haunted the survivors was not just how to live without a Temple, but whether a meaningful Jewish existence was possible at all.10

The Rabbinic Project as Symbolic Suture

Psychohistory posits that the unconscious motivations of groups, particularly in response to collective trauma, shape the course of history.11 The emergence of Rabbinic Judaism in the generations following the destruction is the paradigmatic example of such a response. It represents a radical and profoundly creative effort to construct a new Symbolic order to cover over the void of the Real. This new order performed a crucial substitution: it replaced an authority based on place, lineage, and physical sacrifice (the Temple and the priesthood) with an authority based on text, interpretation, and language (the Torah and the sage).14

This historical shift from Temple to Torah can be mapped directly onto a fundamental psychoanalytic transition. A religious system grounded in physical presence, a tangible connection to the divine, was replaced by a system grounded in absence, in the endless work of interpretation, and in the perpetual deferral of final meaning. This is a move from a logic of presence to a logic of lack, which is the very terrain of Lacanian psychoanalysis. The new rabbinic order was an edifice built of words, a “holy way of life laid down in the Torah as interpreted by rabbis”.15 The figure of the sage, the master of this textual universe, displaced the priest as the central authority. The rabbinic project was, in essence, an attempt to prove that the covenant had not been broken, but had merely been relocated from a physical structure in Jerusalem to the portable, indestructible, and infinitely deep structure of the Oral and Written Law.

The Akiva Narrative as Foundational Fantasy

Within this new symbolic framework, narratives—aggadot—took on a crucial psychological function. They were not intended as objective historical records, a mode of thinking that Rabbinic Judaism largely eschewed 16, but as formative and illustrative stories that shaped the identity and desires of the community.17 The story of Rabbi Akiva, which appears in its most elaborate forms in the Babylonian Talmud tracts Ketubot and Nedarim, stands as the quintessential myth of this new rabbinic order.19

The narrative’s power lies in its function as a foundational fantasy. In Lacanian terms, a fantasy is not a mere daydream but a fundamental scenario that teaches the subject how to desire, how to structure its reality in the face of a traumatic lack.21 The story of Akiva provides the script for the nascent rabbinic subject. It begins with a protagonist who embodies absolute lack: Akiva is a 40-year-old illiterate shepherd, a man outside the symbolic order of Torah, a “nobody” in the new economy of knowledge.22 The narrative then charts his transformation into the ultimate sage, the “Chief of the Sages” 23, through a process of extreme self-abnegation, a 24-year separation from his wife, and total immersion in the “discourse of the Other”—the language of the Torah. The story’s function is thus ideological and psychological: it provides a heroic model for how the trauma of collective lack (the loss of the Temple) can be mastered and converted into a new, more resilient, and ultimately more potent form of subjectivity grounded in the mastery of the signifier. It is the allegory for the Jewish people’s own journey from the Real of destruction to the new Symbolic order of Rabbinic Judaism.

II. The Imaginary Dyad and the Paternal “No”

The narrative of Rabbi Akiva commences not with an act of piety or a moment of intellectual awakening, but with a gaze. It is within the intricate web of initial relationships—between Rachel and Akiva, and between the couple and Rachel’s father, Ben Kalba Savua—that the psychological stage is set for Akiva’s transformation. These opening scenes can be analyzed through Lacan’s theory of the Imaginary order, the register of images, identifications, and ego-formation, and his critical re-evaluation of the Oedipal drama, which hinges on the function of the paternal metaphor, the Nom-du-Père (Name-of-the-Father). The story deliberately stages the failure of the old, pre-rabbinic form of paternal authority to make way for the installation of a new, more powerful symbolic law embodied by the Torah itself.

Rachel and Akiva: The Mirror Stage of the Sage

The story begins with the perception of Rachel, the daughter of the wealthy Ben Kalba Savua. The Talmud states, “The daughter of Ben Kalba Savua saw that he was humble and refined”.19 This act of seeing is the narrative’s catalyst. Rachel’s gaze does not perceive Akiva as he is—an uneducated shepherd, a man of no social standing—but as what he could be. She sees a potential, a hidden quality, an idealized future self. Her subsequent proposition, “If I betroth myself to you, will you go to the study hall to learn Torah?” 19, is the moment she presents this idealized image to Akiva himself.

This dynamic functions as a perfect illustration of Lacan’s concept of the mirror stage.5 The mirror stage describes the moment in an infant’s development when it first recognizes its reflection in a mirror. It identifies with this image, which presents a vision of wholeness and mastery that contrasts with the infant’s actual experience of motor incoordination and fragmentation. This identification with an external image, or imago, is the genesis of the ego. However, this process is fundamentally one of alienation; the “I” is formed by identifying with an “other”.24 Rachel serves as the mirror for Akiva. She offers him an imago of “Rabbi Akiva,” the great scholar, a unified and potent future self. By accepting her condition—”He said to her: Yes” 19—Akiva identifies with this alienating ideal. He accepts this image of an other as his own destiny, setting in motion the entire trajectory of his life. His ego, his sense of self as a future sage, is thus founded upon her perception, her desire.

Ben Kalba Savua: The Impotence of the Imaginary Father

In stark opposition to the nascent desire for symbolic attainment stands the figure of Rachel’s father, Ben Kalba Savua. He represents the established order of authority, a power structure that the rabbinic project seeks to displace. His authority is explicitly derived from his material wealth and social status. He is “one of the wealthy residents of Jerusalem,” a man whose nickname signifies that anyone entering his house “hungry as a dog (kalba), left satisfied (savua)”.22 This power is located squarely within the Lacanian Imaginary register—the realm of surface appearances, social prestige, rivalry, and quantifiable assets.24 He is the imaginary father, a figure whose power is based on what he has, not on a transcendent principle or law.

His reaction to his daughter’s betrothal to an “ignorant and unlearned Akiva” is one of pure narcissistic rage.22 The union is an affront to his Imaginary world order, a violation of the logic of status and wealth. He cannot see the potential that Rachel sees; he sees only the demeaning image of a poor shepherd marrying his daughter. His response is to assert his Imaginary power in the only way he knows: through material control.

The Failed Nom-du-Père

Confronted with this challenge, Ben Kalba Savua issues a prohibitive “No.” The Talmud relates, “Her father heard this and became angry. He removed her from his house and took a vow prohibiting her from benefiting from his property”.19 This act, a vow (neder), is a powerful speech act, but it is a critically flawed one from a Lacanian perspective. It represents a failed invocation of the Nom-du-Père.

In Lacan’s re-reading of Freud, the paternal function is not primarily about the biological father but about a symbolic position. The “Name-of-the-Father” is a master signifier that introduces the subject to the Symbolic order. The paternal “No” (non du père) is the prohibitive law (e.g., the incest taboo) that separates the child from an imaginary, fusional relationship with the mother and structures desire by orienting it within the universal system of language and law.27 A successful paternal intervention is one that “unite[s] (and not to set in opposition) a desire and the Law”.28

Ben Kalba Savua’s vow does the opposite. It is not a structuring, universal law but a capricious act of personal anger. It does not introduce the couple into a wider social order; it violently expels them from it. His “No” does not channel their desire toward a symbolic goal; it attempts to annihilate it through material deprivation. The result is that the couple is cast out not into the Symbolic, but into the Real of abject poverty: “they were so poor that they could not afford pillows or blankets, so they slept on straw”.20 The father’s word, rooted in Imaginary rage, fails to impose symbolic order and instead precipitates an encounter with the raw, destitute Real. This failure is structurally necessary for the narrative. It creates a vacuum in the position of the Law, an emptiness where the true Name-of-the-Father should be. The remainder of the story will be about Akiva’s epic journey to fill this void, not by becoming a father in the biological sense, but by becoming the very incarnation of a new, more powerful Law—the Torah.

The fluidity of this foundational story across different Talmudic sources underscores its mythical, rather than historical, function. As the following table demonstrates, key details shift, revealing that the narrative is not a stable biography but a malleable template designed for didactic and psychological purposes. This de-historicization justifies a structural analysis that treats the characters as functions within a symbolic matrix, allowing for a focus on the invariant psychic structures that persist across all versions.

The variations in the narrative—whether the marriage was consummated, the precise nature of Rachel’s sacrifice, the degree of Akiva’s self-motivation—are less important than the consistent underlying structure: an initial state of profound lack (both material and intellectual), an obstacle posed by an old form of authority, a radical separation for the purpose of symbolic acquisition, and a final return marked by recognition and restitution. It is this deep structure that carries the story’s psycho-historical weight.

[ See below – Appendix 1 ]

III. The Dialectic of Desire: Absence, Torah, and Objet petit a

The 24-year period of Akiva’s absence from Rachel is the narrative’s temporal and psychological core. This prolonged separation is not merely a test of endurance but the very engine of subjective transformation. It is within this radical void that the Lacanian dialectic of desire, lack, and the Symbolic order unfolds. The Talmudic context itself is acutely aware of the transgressive nature of such an absence, framing the story of Akiva against a backdrop of legal discussions concerning the conjugal duties of scholars and the profound suffering of their wives.34 The stories of other rabbis whose prolonged studies lead to their wives’ infertility or even their own deaths serve as cautionary tales.34 Akiva’s story pushes this tension to its absolute limit, suggesting that the genesis of the ultimate sage requires the ultimate experience of lack.

The Structuring Function of Lack

For Jacques Lacan, desire is not a biological need or a simple wish for an object. Desire is born from lack (manque), from a fundamental gap in being that is inaugurated by the subject’s entry into language.5 Language introduces a separation between the subject and the world, and desire is the perpetual, metonymic movement along the chain of signifiers in an attempt to fill this primordial void. Akiva’s 24-year absence is a radical dramatization of this structural lack. The physical separation from Rachel creates the empty space in which his desire for knowledge can be constituted.

This absence is made bearable and meaningful by a promise made in a moment of extreme destitution. While sleeping on straw, Akiva picks the strands from Rachel’s hair and says, “If I had the means I would place on your head a Jerusalem of Gold”.20 This promised tiara is a perfect figuration of what Lacan calls the objet petit a—the object-cause of desire.21 The objet a is not the object that will satisfy desire, for desire is by definition unsatisfiable. Rather, it is the elusive, leftover object, a remnant of a fantasized lost wholeness, that sets desire in motion. It is the surplus-enjoyment (plus-de-jouir) that the subject pursues in other objects.40 The “Jerusalem of Gold” is the fantasized object that stands in for the radical lack of their present reality. It is the promise of a future restitution that gives meaning to the present suffering and propels Akiva’s entire quest. While the tiara is the tangible signifier of this promise, the true, structural objet a that drives the rabbinic subject is the Torah itself. Torah is the object that promises total knowledge and fulfillment, yet its study is by definition an infinite task. It always produces more questions, more interpretations—a “surplus meaning”.40 The pursuit of Torah, like the pursuit of the objet a, does not lead to satisfaction but rather deepens the subject’s engagement with the endless chains of signifiers that constitute the Symbolic order.

The Beit Midrash as the Locus of the “big Other”

Akiva spends his 24 years of absence in the Beit Midrash, the study hall. This location is more than a school; it is the concrete site of what Lacan calls the “big Other”.8 The big Other is not a person but a symbolic structure—the treasury of signifiers, the locus of language, culture, and the Law into which the subject must be inserted. For Akiva, the big Other is the vast, intricate universe of the Torah, both written and oral. His process of study is a process of profound alienation, in the technical Lacanian sense. To become a subject of the Law, he must first lose himself in the language of the Other. He must shed his former identity as Akiva the shepherd and be remade by the discourse of Halakha and Aggadah. This is a painful process of surrendering one’s imaginary sense of self to the impersonal structure of the Symbolic order. It is only by becoming a “symptom” of the Torah, a living embodiment of its discourse, that he can emerge as a new subject who speaks with its authority.

The Talmudic discussion on the appropriate length of time scholars may leave their wives highlights the tension. While Rabbi Eliezer sets the interval for sailors at six months, the Rabbis argue that “Students may leave their homes to study Torah for as long as two or three years without permission from their wives”.35 Akiva’s story takes this permission and extends it to a near-mythical degree, sanctifying the process of alienation in the big Other as the necessary path to mastery.

Rachel’s Voice as the Mandate of the Other

The most pivotal moment in this dialectic occurs at the halfway point. After twelve years, Akiva returns, accompanied by 12,000 students. As he approaches his home, he overhears a conversation. An “old man” (or in other versions, a “wicked neighbor”) taunts Rachel: “For how long will you lead the life of a widow of a living man…?”.19 Her reply is the turning point of the entire saga: “If he would listen to me, he would sit and study for another twelve years”.19

This is not mere wifely encouragement. In the Lacanian schema, this is the voice of the Other articulating its desire. Akiva, overhearing this, understands it not as a personal wish but as a structural mandate. His response, “I have permission to do this,” is a declaration of his complete submission to this mandate.19 He immediately turns back for another twelve years. This scene perfectly illustrates Lacan’s famous and often misunderstood dictum, “desire is the desire of the Other”.6 The subject’s desire is not an authentic, internal impulse but is always constituted in relation to the demands and expectations of the big Other. Akiva’s desire to become a great sage is not “his own”; it is structured by, and finds its legitimacy in, the desire articulated by Rachel. She holds the place of the Other for him, and her words provide the symbolic authorization for him to continue his process of alienation, to pursue the objet a of Torah to its ultimate conclusion. Her voice transforms his potentially transgressive abandonment into a sanctified mission.

This dynamic is underscored by the Talmudic principle that “a woman prefers a kav, i.e., modest means, with conjugal relations to ten kav with abstinence”.34 Rachel’s statement is a radical inversion of this principle. She chooses ten kav of Torah with abstinence over one kav of domestic life, thereby establishing a new hierarchy of values that underpins the entire rabbinic project. Her desire redefines the good, and Akiva, in aligning himself with it, becomes the agent of this new symbolic order.

IV. The Return of the Master: Suture, Symbol, and the Law

Akiva’s final return after 24 years, accompanied by 24,000 students, marks the resolution of the narrative’s central conflicts and the triumphant establishment of the new rabbinic order. This homecoming is not a simple reunion but a series of highly charged symbolic acts that demonstrate the displacement of the old, Imaginary-based authority and the installation of the new, Symbolic authority of the Torah. The conclusion of the story functions as a re-writing of the Oedipal drama for a post-Temple world, where the conflict is not over the mother but over the Law, and where victory is achieved not through patricide but through the symbolic nullification of the father’s word.

“I Am He”: Akiva as the Incarnation of the Law

The narrative’s climax occurs when Ben Kalba Savua, now impoverished and full of regret, seeks out the famous new sage who has arrived in town, hoping the scholar can annul the vow he made against his daughter so many years ago.19 Unaware of the sage’s identity, he presents his case. Akiva, acting as the halakhic authority, poses the critical question: “Did you vow thinking that this husband would become a great man?”.19 Ben Kalba Savua’s reply is steeped in tragic irony: “If I had believed he would know even one chapter or even one halakha I would not have been so harsh”.19

At this moment, Akiva delivers his stunning revelation: “Ani hu“—”I am he”.19 This declaration is a moment of supreme subjective assumption. It signifies far more than a simple identification. Akiva is no longer just the man who was once a shepherd; he has become his function, his title. He is the living embodiment of the Torah, the master signifier in person. This is the culmination of his 24-year process of alienation in the Symbolic order. He has so completely integrated the discourse of the Other that he now speaks as its representative. He has traversed the fantasy and identified with the symbolic mandate given to him by Rachel.

The Nullification of the Vow as Symbolic Castration

Akiva’s first act as this new subject is to nullify his father-in-law’s vow. This is a profound symbolic performance. He does not ask for forgiveness or seek a personal reconciliation. Instead, he wields the impersonal power of Halakha (Jewish Law) to retroactively erase the father’s word. The vow is annulled based on the premise that it was made in error (ta’ut), for had the father known the future, he would not have made it. This legal maneuver is, in psychoanalytic terms, a symbolic castration.

The classical Oedipal complex is resolved when the son, faced with the threat of castration, renounces his desire for the mother and identifies with the father’s law.42 Lacan reframes this as the subject’s necessary submission to the Symbolic order, represented by the Name-of-the-Father.27 In this story, Akiva resolves the Oedipal conflict in a revolutionary way. He does not submit to the law of the biological father-in-law; he overpowers it. By demonstrating that the father’s personal, arbitrary, and Imaginary-based vow is impotent before the transcendent, universal, and Symbolic authority of the Torah, he effectively castrates him. He shows that the father’s word has no ultimate power. Ben Kalba Savua’s reaction—falling on his face, kissing Akiva’s feet, and giving him half his money—is an act of total submission to this new authority.19 Akiva has successfully displaced the impotent imaginary father and installed the Law of the Torah as the true, effective Name-of-the-Father for the community. This act legitimizes the authority of the rabbinic sage over the old aristocracies of wealth and lineage.

“Mine and Yours Are Hers”: Acknowledging the Cause of Desire

The final piece of the psychic puzzle falls into place during the public reunion with Rachel. As she approaches him in her worn clothes, his attendants, not recognizing her, try to push her away. Akiva stops them with the declaration: “Leave her alone, as my Torah knowledge and yours is actually hers” (Sheli v’shelachem shela hu).19

This is the moment of suture that completes the narrative arc. It is a radical public acknowledgment that the entire Symbolic edifice he has constructed—his own mastery (“mine”) and its successful transmission to his thousands of disciples (“yours”)—is not self-generated. It is founded upon, and is an answer to, the desire of the Other, embodied by Rachel. She is the lack, the void, the cause (objet a) from which his entire being as a subject of the Law originates. He recognizes her not just as a supporter, but as the fundamental cause of the entire symbolic economy he now commands. This statement resolves the narrative by revealing the hidden structure of desire that has propelled it from the beginning, reintegrating the cause of his journey with its triumphant result.

The Transmission of the Formula

The story concludes with a brief but essential coda: “Rabbi Akiva’s daughter did the same thing for ben Azzai, who was also a simple person, and she caused him to learn Torah in a similar way”.19 This is not a mere biographical footnote. It is the confirmation that the narrative has established a reproducible formula, what psychohistorians might call a “psychoclass”—a new psychogenic mode for childrearing or, in this case, sage-making.13 The structure is now a transmissible model: a woman’s desire, functioning as the desire of the Other, creates a structural lack that a man fills by alienating himself in the Symbolic order of Torah, ultimately returning as a master of the Law. This formula ensures the perpetuation of the rabbinic project, demonstrating that the path of Akiva is not a unique, unrepeatable miracle but a template for the creation of future generations of sages. The narrative has not just told a story; it has encoded a program for the reproduction of its own hero.

V. Conclusion: The Rabbinic Fantasy and the Legacy of Akiva

The Talmudic saga of Rabbi Akiva and Rachel is far more than a hagiographic tale or a historical account. When read through the combined lenses of psychohistory and Lacanian psychoanalysis, it reveals itself as a foundational fantasy for Rabbinic Judaism, a powerful narrative framework that emerged from the ashes of the Second Temple to structure a new form of Jewish subjectivity. The story operates as a psychic blueprint, teaching the post-destruction Jewish subject how to desire, how to navigate the trauma of existence, and how to find meaning in a world defined by profound loss. It is a narrative that does not simply describe a new reality; it actively produces the psychological conditions for that reality to exist.

The Story as a Structuring Fantasy

The narrative provides a masterful script for mastering the traumatic Real. The destruction of the Temple left a void, an unsymbolizable lack at the heart of the Jewish world. The story of Akiva confronts this lack head-on by beginning with a protagonist who is the very embodiment of it—an unlettered man of forty, a void of Torah knowledge. The fantasy then demonstrates, step by step, how this void can be not just filled but transformed into the source of ultimate potency. It teaches that subjectivity is not a given state but is forged through a painful but necessary process: the acceptance of a radical lack, a profound alienation in the language of the big Other (the Torah), and the relentless pursuit of an impossible object-cause of desire (objet a). The 24-year separation, the poverty, and the deferral of domestic life are not presented as tragedies but as the necessary price for entry into the Symbolic order and the mastery of the Law. The fantasy works by converting the pain of loss into a meaningful, heroic quest for symbolic acquisition.

The Rabbinic Subject

The ideal rabbinic subject, as modeled by the transformed Akiva, is a new type of hero for a new era. He is a subject who has undergone a symbolic castration—not as a punishment, but as a condition of his power. He has accepted his fundamental lack and renounced the pursuit of Imaginary satisfactions like wealth and status, which were the domain of the failed father figure, Ben Kalba Savua. His potency is found not in what he has but in what he knows, or more precisely, in his mastery of the signifier. His authority is legitimized by his ultimate, public recognition that his knowledge is not for himself. His declaration, “Mine and yours are hers,” is the ethical core of the rabbinic subject: the understanding that one’s symbolic power is a product of, and must be offered back to, the desire of the Other. This creates a subject whose very being is intertwined with the community and the textual tradition he serves, a stark contrast to the individualistic authority of the wealthy patriarch.

Legacy and Psychohistorical Impact

As a psychohistorical document, the story of Akiva is not a reflection of the past but an intervention in the future. It became a cornerstone of rabbinic identity, providing a powerful psychological model for generations of scholars. It sanctified a life of intense intellectual pursuit, often at the great personal cost of familial presence, by framing this separation not as abandonment but as the highest form of devotion. It provided a compelling answer to the traumatic question of “What now?” that echoed in the wake of 70 CE. The answer it offered was a heroic and, crucially, replicable narrative of personal and collective reconstitution through the Word. By displacing the authority of the father of the household with the authority of the “Father” of the Law, the story provided the ideological and psychological justification for the new rabbinic elite. In the end, the story of Rabbi Akiva demonstrates the profound power of narrative to shape reality. It is a testament to how a traumatized community can remake itself by telling a new story, a story that transforms a gaping wound into the very condition of its rebirth and endurance.

A critique of the analysis and focus of the article – Google NotebookLM

Works cited

- Responding to Catastrophe: The Impact of the Destruction of the …, accessed on

October 10, 2025, https://www.bac.org.il/en/events/?seriesID=1107 - The Temple and its Destruction | My Jewish Learning, accessed on October 10,

2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-temple-its-destruction/ - Lacanian Psychoanalysis and Language | Intro to Literary Theory Class Notes –

Fiveable, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://fiveable.me/introduction-to-literary-theory/unit-5/lacanian-psychoanalysis-language/study-guide/81aKW18Ny6O5lbk2 - Jacques Lacan – The Symbolic – The Imaginary – The Real | Inner Worlds / Outer

Space, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://melaniemenardarts.wordpress.com/2010/10/09/jacques-lacan-the-symbo

lic-the-imaginary-the-real/ - Lacanian Psychoanalysis: A Guide to Therapy, Desire & Self …, accessed on

October 10, 2025, https://uktherapyguide.com/what-is-lacanian-psychoanalysis - Lacanian Psychoanalysis: A Comprehensive Overview – – Taproot Therapy

Colective, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://gettherapybirmingham.com/lacanian-psychoanalysis-a-comprehensive-o

verview/

- Causes of the Temple’s Destruction – Josephus, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://josephus.org/causeofDestruct.htm - What Is Jacques Lacan’s Mysterious Big Other? – TheColector, accessed on

October 10, 2025, https://www.thecolector.com/jacques-lacan-big-other/ - Jacques Lacan and the “Others”. Big Other is watching… | by Babek Hürremi

Kızılhanoğuz YUSUFOĞLU | Medium, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://medium.com/@babek.hurremi.k.yusufoglu/jacques-lacan-and-the-others

cdf9e445c0ff - WHEN JUDAISM LOST THE TEMPLE – Macquarie University, accessed on October

10, 2025,

https://figshare.mq.edu.au/articles/thesis/When_Judaism_lost_the_Temple_crisis_

and_response_in_4_Ezra_and_2_Baruch/19444439/1/files/34545551.pdf - events.orinyc.org, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://events.orinyc.org/introduction-to-psychohistory-for-mental-health-profes

sionals/#:~:text=Psychohistory%20probes%20the%20conscious%20and,are%20

central%20areas%20of%20concern. - Introduction to psychohistory for mental health professionals – Object …,

accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://orinyc.org/introduction-to-psychohistory-for-mental-health-professionals

/ - Psychohistory – Wikipedia, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychohistory - Siege of Jerusalem (70 CE) – Wikipedia, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Jerusalem_(70_CE) - Rabbinic Judaism in Late Antiquity | Encyclopedia.com, accessed on October 10,

2025,

https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/rabbinic-judaism-late-antiquity - The Idea of History in Rabbinic Judaism | New Blackfriars | Cambridge Core,

accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/new-blackfriars/article/idea-of-history-i

n-rabbinic-judaism/03C86D618F13929971CFB417643297FB - The Place of Story and Storyteling in Messianic Jewish Ministry: Rediscovering

the Lost Treasures of Hebraic Narrative – Kesher Journal, accessed on October

10, 2025,

https://www.kesherjournal.com/article/the-place-of-story-and-storyte ling-in-me

ssianic-jewish-ministry-rediscovering-the-lost-treasures-of-hebraic-narrative/ - An Alternative Theology of Destruction: Aligning with Suffering Jewish Flesh,

accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://bu letin.hds.harvard.edu/an-alternative-theology-of-destruction-aligning

with-suffering-jewish-flesh/ - Rachel and Rabbi Akiba: A 4-Act Story – Sefaria, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/417650 - Nedarim 50a – Sefaria, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://www.sefaria.org/Nedarim.50a - Objet petit a – Wikipedia, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Objet_petit_a - The Story of Rachel, The Wife of Rabbi Akiva – TORCH: Torah Weekly, accessed on

October 10, 2025, https://www.torchweb.org/torah_detail.php?id=623 - Rabbi Akiva – Wikipedia, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabbi_Akiva - The Imaginary (psychoanalysis) – Wikipedia, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Imaginary_(psychoanalysis) - Nedarim 50.a – Steinsaltz Center, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://steinsaltz-center.org/portal/library/Talmud/Nedarim/chapter/50.a - The folowing is a brief discussion of Lacan’s three “Orders”. The text is taken from

An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, Dylan Evans, London:

Routledge, 1996. – Timothy R. Quigley, accessed on October 10, 2025,

http://timothyquigley.net/vcs/lacan-orders.pdf - Name of the Father – Wikipedia, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Name_of_the_Father - Name-of-the-Father | Encyclopedia.com, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://www.encyclopedia.com/psychology/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-an

d-press-releases/name-father - Ketubot 60 – 66 « The Weekly Daf « – Ohr Somayach, accessed on October 10,

2025, https://ohr.edu/this_week/the_weekly_daf/373 - Nedarim: 50a – The Talmud – Chabad.org, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://www.chabad.org/torah-texts/5451078/The-Talmud/Nedarim/Chapter-6/50

a - Ketubot 62b – Sefaria, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://www.sefaria.org/Ketubot.62b?lang=en - Ketubot 62b-63a – Sefaria, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://www.sefaria.org/Ketubot.62b-63a - The Rime of the Ancient Talmudist (Ketubot 62b) – Ilana Kurshan, accessed on

October 10, 2025,

https://ilanakurshan.com/2006/07/14/the-rime-of-the-ancient-talmudist-ketubot-62b/ - Lacanianism – Wikipedia, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lacanianism - pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15822424/#:~:text=The%20objet%20petit%20a

%20is%20a%20fantasy%20that%20functions%20as,impossible%20and%20even

%20deadly%20enjoyment. - Objet petit a – (Intro to Literary Theory) – Vocab, Definition, Explanations |

Fiveable, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://fiveable.me/key-terms/introduction-to-literary-theory/objet-petit-a - What does Objet petite’a mean (Lacan)? : r/askphilosophy – Reddit, accessed on

October 10, 2025,

https://www.reddit.com/r/askphilosophy/comments/5sb8s6/what_does_objet_peti

tea_mean_lacan/ - Explain Big Other? – lacan – Reddit, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://www.reddit.com/r/lacan/comments/i0v0om/explain_big_other/ - Psychoanalysis – Wikipedia, accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychoanalysis - An Introduction and Brief Overview of Psychoanalysis – PMC – PubMed Central,

accessed on October 10, 2025,

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10575551/

Glossary

objet petit a – Judaism Scholar

The term “objet petit a” originates from the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan, a 20th-century French psychoanalyst. While this concept is not directly related to Jewish theology or tradition, I can provide a brief explanation of its meaning within its original context.

Explanation of “Objet Petit a”

In Lacanian psychoanalysis, “objet petit a” (French for “object small a”) refers to the unattainable object of desire. It represents the thing that we seek but can never fully obtain, as it is tied to a sense of lack or incompleteness inherent in human existence. This “object” is not a tangible thing but rather a symbolic placeholder for what is missing in our lives, often linked to the unconscious and the structure of desire.

Lacan used this concept to explore how human desire is shaped by the interplay between the self, the other, and the symbolic order (language, culture, and societal norms). The “objet petit a” is central to understanding the dynamics of desire and the ways in which individuals relate to their own sense of fulfillment or lack thereof.

Connection to Jewish Thought

While “objet petit a” is a psychoanalytic concept, one could draw thematic parallels to certain ideas in Jewish philosophy and mysticism. For example:

Tikkun Olam (Repairing the World): The Jewish concept of Tikkun Olam involves striving to perfect the world, even though complete perfection may be beyond human reach. This ongoing effort reflects a deep yearning for an ideal state that remains elusive.

The Infinite and the Finite: In Jewish thought, there is often a tension between the finite human experience and the infinite nature of God (Ein Sof). The yearning for closeness to God, while knowing that God’s essence is ultimately beyond human comprehension, could be seen as a kind of “unattainable desire.”

Nom-du-Père – Judaism Scholar

The term “Nom du Père,” which translates from French as “Name of the Father,” originates from psychoanalytic theory, particularly the work of Jacques Lacan, a 20th-century French psychoanalyst. While this concept is not directly rooted in Jewish theology or tradition, it can be explored in light of Jewish thought and its potential intersections with broader philosophical and psychoanalytic ideas.

Lacanian Context

In Lacanian psychoanalysis, the “Name of the Father” is a central concept that refers to the symbolic authority and structure introduced into a child’s psyche. It represents the law, order, and cultural norms that regulate human behavior and relationships. The “Name of the Father” is not about a literal father but rather the symbolic function of the father figure as a mediator of societal rules and language. It is through this “name” that the child enters the symbolic order, which is the realm of language, culture, and social structures.

Jewish Perspectives on Fatherhood and Authority

In Jewish tradition, the concept of fatherhood carries profound spiritual and symbolic significance. The Hebrew word for father, אב (Av), is often associated with both biological and spiritual roles. The father is seen as a transmitter of tradition, values, and Torah knowledge. This role aligns with the idea of introducing the child to a broader framework of meaning and responsibility, akin to the symbolic function described in Lacanian theory.

God as “Father”

In Jewish theology, God is often referred to as “Avinu” (Our Father), as in the prayer Avinu Malkeinu (“Our Father, Our King”). This reflects the dual role of God as both a loving parent and a sovereign authority. The “Name of the Father” in this context could be seen as the divine authority that establishes moral and spiritual law, guiding individuals and the community.

The Role of the Father in Jewish Mysticism

In Kabbalistic thought, the concept of the father is symbolically linked to Chokhmah (Wisdom), one of the ten Sefirot (emanations) through which God interacts with the world. Chokhmah represents the initial spark of divine wisdom and creativity, which is then developed and nurtured through Binah (Understanding), often associated with the mother. This dynamic interplay between Chokhmah and Binah mirrors the psychoanalytic idea of the father introducing structure and the mother providing nurturing.

Intersections Between Lacanian and Jewish Thought

While Lacan’s “Name of the Father” is a secular psychoanalytic concept, it resonates with certain aspects of Jewish thought:

- Transmission of Law and Tradition: Just as the “Name of the Father” introduces the child to the symbolic order, the Jewish father (and by extension, the family and community) introduces the child to the Torah and the mitzvot (commandments), which are the foundation of Jewish life.

- Authority and Structure: The “Name of the Father” as a symbol of authority parallels the role of God as the ultimate source of moral and spiritual authority in Judaism.

- Language and Meaning: In Lacanian theory, the “Name of the Father” is tied to language and the symbolic order. In Judaism, the Hebrew language and the names of God hold profound significance, serving as a bridge between the divine and the human.

Conclusion

The “Nom du Père” or “Name of the Father” in Lacanian psychoanalysis emphasizes the role of symbolic authority and the introduction of the individual into the realm of language and culture. In Jewish thought, the father plays a similar role in transmitting tradition, values, and divine law. While the two frameworks come from different intellectual traditions, they share a focus on the importance of authority, structure, and the transmission of meaning across generations.

points de capiton – Judaism Scholar

The term “points de capiton” (French for “quilting points”) originates from the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan, a 20th-century French psychoanalyst. While this concept is not directly related to Jewish theology or tradition, I can provide an explanation of its meaning within its original context and explore any thematic parallels to Jewish thought.

Lacanian Context: What Are “Points de Capiton”?

In Lacanian psychoanalysis, “points de capiton” refers to the “anchoring points” or “quilting points” that stabilize meaning within language and the symbolic order. Lacan uses this metaphor to describe how certain key signifiers (words, ideas, or symbols) serve to “pin down” the otherwise fluid and shifting relationship between signifiers (words) and the signified (the concepts or meanings they represent).

Without these anchoring points, meaning would remain unstable and endlessly deferred, as language is inherently dynamic and relational. The “points de capiton” provide a sense of coherence and structure to our understanding of the world, even though this coherence is ultimately constructed and not absolute.

For example, in a political ideology, terms like “freedom” or “justice” might serve as quilting points, anchoring a network of ideas and giving them a sense of stability and shared meaning within that ideological framework.

Thematic Parallels in Jewish Thought

While “points de capiton” is a psychoanalytic concept, one might draw thematic parallels to certain ideas in Jewish philosophy and tradition:

- Torah as an Anchor of Meaning:

In Judaism, the Torah serves as a central and unchanging anchor for Jewish life and thought. It provides a framework of meaning and stability amidst the complexities and uncertainties of human existence. The Torah’s commandments (mitzvot) and teachings act as “quilting points” that connect the Jewish people to God, to each other, and to their purpose in the world. - The Role of Language in Creation:

In Jewish mysticism, language is seen as a fundamental aspect of creation. The world was created through divine speech, as described in Genesis (“And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light”). The Hebrew letters and words are considered to have intrinsic spiritual power, anchoring the physical and metaphysical realms. This resonates with the idea of “quilting points” as stabilizing elements within a broader system of meaning. - Halakha (Jewish Law) as a Framework:

Halakha provides a structured framework for Jewish life, offering clear guidelines for behavior and decision-making. It serves as a stabilizing force, much like “points de capiton,” by anchoring the individual’s actions and choices within a larger, divinely ordained system of meaning. - Kabbalistic Sefirot as Anchors of Divine Emanation:

In Kabbalah, the Sefirot (the ten emanations through which God interacts with the world) can be seen as “anchoring points” that structure the flow of divine energy and meaning into creation. Each Sefirah represents a specific attribute or aspect of God, providing a framework for understanding the relationship between the infinite (Ein Sof) and the finite world.

Summary

In Lacanian theory, “points de capiton” are the anchoring points that stabilize meaning within the fluid system of language and the symbolic order. While this concept is rooted in psychoanalysis, it has thematic parallels in Jewish thought, particularly in the role of Torah, language, Halakha, and the Sefirot as stabilizing forces that provide coherence and meaning within the Jewish worldview. These parallels highlight the universal human need for anchors of meaning in navigating the complexities of life and existence.

====================================================================================================

====================================================================================================

Appendix 1

The Babylonian Talmud: A Tale of Two Talmuds Within One

The most detailed and widely known accounts of Rabbi Akiva and Rachel’s story are found in the Babylonian Talmud, specifically in tractates Ketubot (62b-63a) and Nedarim (50a). While largely consistent, these two versions offer slightly different nuances.

- Ketubot 62b-63a: This is the most extensive and dramatic telling of the story. It portrays Rachel, the daughter of the wealthy Kalba Savua, as the initiator of Akiva’s journey to Torah scholarship. She recognizes the “humble and refined” nature of her father’s uneducated shepherd and proposes marriage on the condition that he dedicates himself to study. Her father, enraged by the match, disowns her and vows that she will not benefit from his property.This version emphasizes the immense personal sacrifice of both Rachel and Akiva. They live in abject poverty, with the Talmud recounting that they slept on straw. The narrative famously describes Akiva’s 24-year absence, divided into two 12-year periods. Upon his initial return with 12,000 students, he overhears a neighbor chiding Rachel for her long-suffering. Rachel’s response—that if it were up to her, he would study for another 12 years—prompts Akiva to return to the academy without even revealing himself.The climax of this version is Akiva’s triumphant return with 24,000 disciples. When his attendants try to push away the shabbily dressed Rachel, Akiva famously declares, “Leave her! For my Torah and yours are hers.” This powerful statement solidifies Rachel’s central role in his success. The narrative concludes with the reconciliation between Kalba Savua and his daughter and son-in-law, after Akiva, now a great sage, helps his father-in-law annul his vow.

- Nedarim 50a: This telling is more concise and is presented in the context of a discussion about the annulment of vows. It corroborates the main points of the Ketubot narrative: Rachel’s recognition of Akiva’s potential, her father’s disapproval and vow, and their subsequent poverty. However, this version places a greater emphasis on the legal aspects of the story, particularly the eventual annulment of Kalba Savua’s vow.A key detail in the Nedarim account is the story of Akiva being inspired by water dripping on a stone, realizing that if water can wear away stone, the words of Torah can certainly penetrate his heart. This element, while often associated with the broader narrative, is explicitly mentioned here.

The Jerusalem Talmud: A Different Perspective on Sacrifice

The Jerusalem Talmud (Yerushalmi) presents a significantly different, and less detailed, account of Rachel’s contribution to Rabbi Akiva’s studies. In Shabbat 6:1, the Yerushalmi tells of Rabbi Akiva presenting his wife with a “Jerusalem of Gold” tiara. When the wife of the sage Rabban Gamliel expresses envy, her husband replies, “Would you have done for me what she did for her husband? She sold the braids of her hair and he studied Torah with the proceeds.”

This version offers a distinct form of sacrifice. Instead of enduring a prolonged separation and extreme poverty while living as a “widow with a living husband,” the Yerushalmi’s Rachel actively supports her husband’s studies through the sale of her own hair. This account suggests a more immediate and tangible form of financial support, without the dramatic 24-year separation that is central to the Babylonian Talmud’s narrative.

Comparative Analysis: Key Differences and Their Implications

| Narrative Element | Babylonian Talmud (Ketubot & Nedarim) | Jerusalem Talmud (Shabbat) |

| Rachel’s Primary Sacrifice | Enduring 24 years of poverty and solitude. | Selling her hair to financially support his studies. |

| Duration of Akiva’s Absence | 24 years (in two 12-year stints). | Not specified, but a prolonged absence is not the central theme. |

| Narrative Focus | The epic journey of transformation through sacrifice and dedication. | A poignant illustration of spousal devotion and support. |

| Rachel’s Agency | Proactively sets the condition for marriage and encourages his extended studies. | Actively provides the financial means for his education. |

These differences in the Talmudic accounts may reflect the distinct cultural and intellectual environments in which the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds were compiled. The Babylonian Talmud, known for its elaborate narratives and intricate legal discussions, presents a more epic and dramatic version of the story. This telling may have served as a powerful source of inspiration for Babylonian scholars who often left their families for extended periods to study in the great academies.

The Jerusalem Talmud’s version, with its focus on a more immediate and personal sacrifice, offers a different model of spousal support. It highlights the tangible contributions a wife could make to her husband’s scholarly pursuits within a context where such prolonged separations may have been less common or idealized.

The Midrashic Tradition: Avot de-Rabbi Natan

The midrashic work Avot de-Rabbi Natan also contains a version of the story. This account is significant because it is one of the earliest sources to explicitly name Rabbi Akiva’s wife as Rachel. It largely aligns with the Babylonian Talmud’s narrative, emphasizing Rachel’s foresight in recognizing Akiva’s potential and her unwavering support throughout their years of poverty.

In conclusion, while the core elements of the Rabbi Akiva and Rachel narrative—her recognition of his potential and her immense sacrifice for his Torah study—remain consistent, the specific details and the overall emphasis of the story vary across Talmudic sources. The Babylonian Talmud presents a grand, epic narrative of transformation over a long period of separation, while the Jerusalem Talmud offers a more intimate and immediate portrait of spousal devotion. Together, these different versions enrich our understanding of this iconic rabbinic couple and the diverse ways in which their story was told and understood within the Jewish tradition.

===================================================================================================

===================================================================================================