DATE: 2025-09-08 Judaic Scholar AI / Peter Dixon

Notebook LM Deep Dive Audio Podcast

Introduction

This report provides a comprehensive academic analysis of the evolution of Jewish faith and identity over the century spanning from 1924 to 2024. The objective is to synthesize modern philosophical and psychological perspectives to create an objective scholarly framework for researchers, theologians, and social scientists. The past hundred years have been a period of unprecedented upheaval, trauma, and intellectual dynamism for Jewish communities worldwide. From the cataclysm of the Holocaust to the establishment of the State of Israel, and from the pressures of assimilation in the diaspora to the rise of new philosophical and psychological paradigms, Jewish identity has been continuously negotiated and redefined. This analysis delves into the profound psychological impacts of historical events, exploring themes of trauma, resilience, and adaptation. Concurrently, it examines the rich philosophical inquiries that have emerged, from existentialist explorations of dialogue and faith to phenomenological ethics and critical theory’s deconstruction of modernity. Finally, the report addresses the persistence of historical challenges and contemporary misconceptions that continue to shape Jewish life and intercommunity relations. By integrating these diverse fields of study, this document aims to provide a nuanced and multifaceted understanding of the nature and history of Jewish faith in the modern era, moving beyond simplistic narratives to capture its complexity, resilience, and enduring intellectual vitality.

The Psychological Landscape of Jewish Identity in the 20th and 21st Centuries

The psychological fabric of Jewish identity over the past century has been woven from threads of profound trauma, remarkable resilience, and the constant negotiation of belonging in diverse cultural landscapes. The collective and individual psyche of Jewish communities has been indelibly shaped by historical events that have tested the limits of human endurance and adaptation. This section explores the deep psychological scars left by the Holocaust, the complex dynamics of diaspora and assimilation, and the inherent mechanisms of resilience that have enabled survival and growth. Through a modern psychological lens, we can analyze how these experiences have been processed, transmitted across generations, and integrated into the contemporary Jewish experience, creating a unique and multifaceted psychological profile.

The Enduring Legacy of the Holocaust

The Holocaust stands as a defining event of the 20th century, leaving an enduring psychological legacy that extends far beyond the immediate survivors. The long-term impacts on those who endured the genocide are profound and multifaceted, characterized by persistent mental health challenges. Research conducted decades after the event reveals that survivors exhibit significantly higher frequencies of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and generalized anxiety. These symptoms, including intrusive memories, avoidance behaviors, and heightened arousal, often persist for a lifetime, with studies showing that a high percentage of aging survivors experience chronic PTSD, frequently co-morbid with other severe psychiatric disorders. This trauma can be reactivated in later life by triggers such as physical illness, retirement, or anniversaries, exacerbating psychological distress. Beyond symptomatology, the trauma has been shown to induce neurobiological changes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies on survivors have identified irreversible reductions in gray matter in stress-related brain regions, such as the insula and prefrontal cortex, even in individuals who were traumatized as children. These alterations are linked to a heightened vulnerability to mental health disorders and suggest that extreme stress can inflict lasting damage on the brain’s structure and function.

A critical dimension of the Holocaust’s psychological aftermath is the phenomenon of intergenerational trauma, where the effects are transmitted to subsequent generations. This transmission is not merely psychological but has a biological basis in epigenetics. Studies on the children of Holocaust survivors have found altered gene expression in stress-related genes, such as FKBP5, which are associated with an increased risk for anxiety disorders. These epigenetic modifications suggest that parental trauma can be passed down biologically, predisposing offspring to heightened emotional vulnerability, worry, and mistrust, even without direct exposure to the traumatic events. This inherited vulnerability is often compounded by parenting styles influenced by the parents’ trauma, which may include patterns of overprotection or emotional unavailability. However, the legacy is not solely one of pathology. Alongside the transmission of trauma, many survivors and their descendants demonstrate remarkable posttraumatic growth (PTG). This involves finding new meaning in life, a greater appreciation for relationships, and a strengthened sense of personal resilience. For many, the process of rebuilding their lives, forming communities, and bearing witness has served as a powerful compensatory mechanism, allowing for adaptation and a sense of purpose despite pervasive psychological suffering. The challenges of postwar reconstruction were immense, with many survivors living in displaced persons camps for years, facing persistent antisemitism, and struggling with the loss of family and social networks. The societal context in which survivors rebuilt their lives played a crucial role, with evidence suggesting that those who settled in supportive community environments, such as in Israel, experienced better psychological well-being and social adjustment.

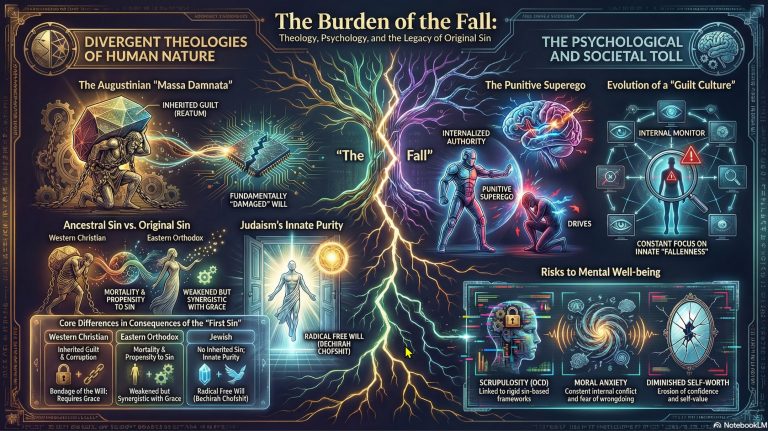

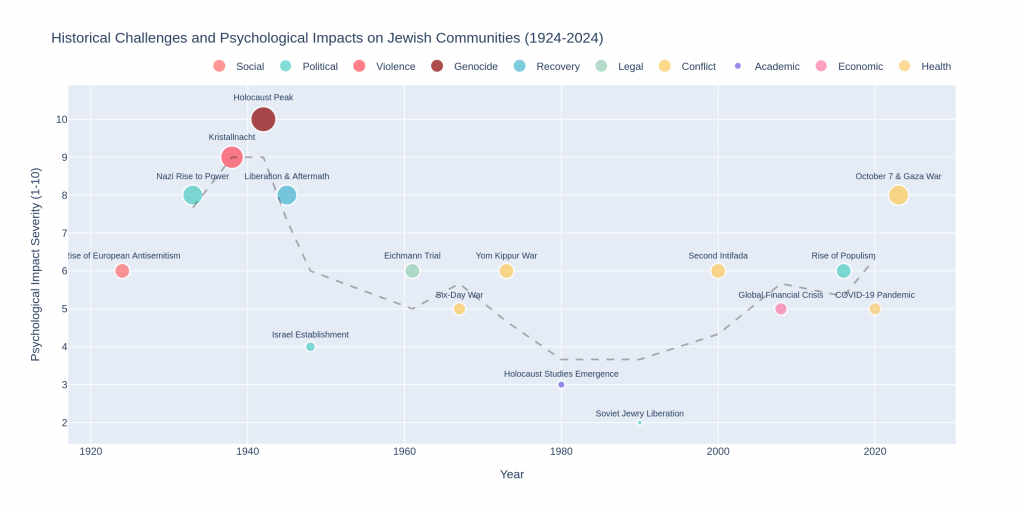

This chart illustrates the complex interplay of historical trauma, community support, assimilation pressures, and internal resilience mechanisms that have shaped the psychological landscape of modern Jewish identity.

Diaspora, Displacement, and Adaptation

The Jewish experience has been intrinsically linked to diaspora and displacement for millennia, a reality that profoundly shaped its psychological and social contours long before the 20th century. The historical roots of this dispersion, from the Babylonian exile to the Roman conquest, established a recurring pattern of involuntary movement, loss of homeland, and the need to adapt to new and often hostile environments. This long history of living as a minority created a collective psychology attuned to the challenges of acculturation and the preservation of identity. In the 20th and 21st centuries, these dynamics were amplified by events like the Holocaust and subsequent migrations, which transformed Jewish communities from refugee populations into transnational networks. The psychological challenges inherent in the diaspora experience are significant, often manifesting as acculturative stress, which encompasses the anxiety and depression arising from navigating new social norms, languages, and cultural expectations. A related concept is cultural bereavement, the profound grief associated with the loss of one’s native culture, social structures, and sense of identity, which can lead to symptoms of guilt, anger, and morbid thoughts.

The legacy of historical traumas, particularly the Holocaust, has also contributed to a specific form of collective anxiety within diaspora communities, sometimes termed “annihilation anxiety.” This is a deep-seated fear of cultural or physical extinction that can influence mental health, identity formation, and community behavior. The perception of xenophobia and antisemitism in host societies can exacerbate this psychological strain, hindering processes of integration and assimilation. However, the narrative of the Jewish diaspora is equally one of resilience and creative adaptation. Communities have consistently developed robust coping mechanisms to navigate these challenges. Adaptation is not a passive process but an active strategy involving the building of strong social and organizational networks, the preservation and evolution of cultural and religious practices, and strategic engagement with host societies. This has often led to the formation of hybrid identities, where individuals negotiate and blend elements of their culture of origin with that of their adopted home, creating a rich and dynamic cultural tapestry. This process demonstrates that diaspora life is not necessarily one of isolation but can be a source of cultural innovation and strength, fostering a unique resilience that allows for both integration and the maintenance of a distinct identity.

Assimilation Pressures and Identity Conflicts

Throughout the 20th century, Jewish communities, particularly in the West, faced intense pressures to assimilate into dominant gentile societies. This process, involving the adoption of the host culture’s norms, values, and behaviors, was often seen as a pathway to social acceptance, economic mobility, and safety from persecution. However, it came at a significant psychological cost, creating profound identity conflicts for individuals and communities. The pressure to dilute or abandon distinct ethnic and religious practices in favor of conformity generated significant internal and interpersonal tension. Psychologically, this manifested in a range of issues, including chronic anxiety, feelings of guilt over the perceived betrayal of one’s heritage, and deep-seated identity crises. Individuals were often caught between the expectations of their families and communities, who sought to preserve tradition, and the demands of a wider society that rewarded cultural conformity. This was particularly acute for second-generation immigrants, who navigated the complex space between their parents’ world and the new world they inhabited.

The nature of these assimilation pressures varied by context. In the United States, the “melting pot” ideology encouraged immigrants to shed their particularities, leading to negotiations over everything from religious observance and gender roles to language and career choices. This often resulted in what has been termed the “anxiety of assimilation,” a psychological state characterized by a persistent sense of being caught between two worlds. In the former Soviet Union, assimilation was not merely a social pressure but a state-imposed policy that actively suppressed Jewish religious and ethnic expression, leading to a forced dilution of identity and a psychological detachment from Jewishness for many. The Holocaust cast a long and complex shadow over these dynamics. On one hand, the trauma intensified fears of Jewish extinction, leading some to double down on preserving Jewish identity. On the other hand, it created a pervasive sense of vulnerability that, for some, made the prospect of blending in and disappearing into the majority culture seem like a viable survival strategy. The psychological toll of burying one’s past and identity to adopt a new one was immense, often leading to a sense of profound loss and displacement. In response to these pressures, Jewish communities demonstrated remarkable adaptability, developing a spectrum of strategies from cultural pluralism, which sought to maintain distinctiveness within a larger society, to various forms of identity revival, including renewed interest in religious movements, Zionism, and cultural heritage.

Mechanisms of Jewish Resilience

In the face of centuries of persecution, displacement, and the unparalleled trauma of the Holocaust, the persistence and vitality of Jewish communities point to powerful mechanisms of psychological resilience. This resilience is not merely the absence of pathology but an active process of adaptation, coping, and growth in the face of extreme adversity. One of the key psychological mechanisms identified in survivors of persecution is the capacity for posttraumatic growth (PTG). This phenomenon involves positive psychological changes experienced as a result of struggling with major life crises. Survivors often report a greater appreciation for life, deeper relationships, a stronger sense of personal strength, and a shift in life philosophy. This growth can serve to compensate for some of the psychological damage inflicted by trauma, allowing individuals to find meaning and purpose even after devastating loss. Adaptive defense mechanisms also play a crucial role, with strategies such as intellectualization, humor, and sublimation enabling individuals to manage overwhelming stress and integrate traumatic experiences into their life narratives without being completely consumed by them.

Community and social factors are central to Jewish resilience. The importance of group belonging cannot be overstated. For survivors and their descendants, participating in community groups, sharing narratives, and engaging in collective mourning rituals helps to normalize their experiences, reduce isolation, and shift their identity from one of pure victimhood to one of survival and empowerment. Strong organizational structures, educational institutions, and religious practices provide a framework of support and continuity that buffers individuals against acculturative stress and historical trauma. Family dynamics are another critical mediator. While parental trauma can sometimes lead to dysfunctional patterns that transmit anxiety to the next generation, balanced and cohesive family environments can effectively transmit resilience. The modeling of adaptive coping strategies, open communication about the past, and the instilling of a strong, positive cultural identity can equip children with the tools to navigate their own life challenges. This transgenerational transmission of resilience is a vital counter-narrative to the transmission of trauma, demonstrating that strengths, like vulnerabilities, can be passed down. Ultimately, Jewish resilience is a multifaceted construct, woven from individual psychological fortitude, strong communal bonds, and a rich cultural and religious tradition that provides a deep well of meaning and continuity.

Philosophical Inquiries into Jewish Thought (1924-2024)

The 20th century was a period of profound intellectual ferment in Jewish philosophy, as thinkers grappled with the challenges of modernity, the crisis of faith following the Holocaust, and the complex questions of identity in a rapidly changing world. Engaging deeply with the major philosophical currents of the time—including existentialism, phenomenology, and critical theory—Jewish philosophers forged new paths for understanding the nature of faith, ethics, and human existence. This era saw a decisive turn away from abstract, systematic metaphysics toward a philosophy grounded in lived experience, ethical relationships, and the interpretation of both sacred texts and historical events. Thinkers from Martin Buber to Emmanuel Levinas and the intellectuals of the Frankfurt School did not merely apply external philosophies to Jewish themes; they created unique syntheses that offered powerful critiques of Western thought while revitalizing Jewish intellectual traditions for a new age.

![Timeline of key historical events affecting Jewish philosophy and psychology 1924-2024]() This timeline charts the major historical events, psychological shifts, and philosophical movements that have defined the Jewish experience over the past century, highlighting their interconnectedness.

This timeline charts the major historical events, psychological shifts, and philosophical movements that have defined the Jewish experience over the past century, highlighting their interconnectedness.

Existentialism and the Philosophy of Dialogue

In the early to mid-20th century, Jewish existentialism emerged as a powerful response to the alienation and depersonalization of modern life, seeking to ground faith and philosophy not in abstract dogma or rationalist systems, but in the concrete, lived experience of the individual. Two of its most influential proponents, Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig, championed a “new thinking” that prioritized relationship, encounter, and dialogue. Martin Buber’s seminal work, I and Thou, articulated a fundamental distinction between two modes of being: the I-Thou relationship and the I-It relationship. The I-It relation is the realm of experience and utility, where we treat others and the world as objects to be analyzed, used, or categorized. This mode, Buber argued, dominates modern society, leading to alienation and a hollowing out of human existence. In contrast, the I-Thou relationship is one of genuine encounter, a direct, mutual, and holistic engagement where two beings meet in their full presence. For Buber, it is only in the I-Thou encounter—whether with another person, a work of art, nature, or God (the “Eternal Thou”)—that true life and meaning are found. This philosophy of dialogue posits that humanity is realized not in isolation, but in the space between individuals, in the sacred act of turning toward one another with openness and respect.

Franz Rosenzweig, in his monumental work The Star of Redemption, written on postcards from the trenches of World War I, offered a profound critique of Western philosophy’s tendency to reduce the particularity of God, humanity, and the world to a single, all-encompassing totality, as exemplified by Hegel. Against this abstract idealism, Rosenzweig began his philosophy from the concrete reality of human finitude and the fear of death. He structured his thought around three irreducible elements—Creation (the world), Revelation (the relationship between God and humanity), and Redemption (the ultimate hope for the future). For Rosenzweig, Revelation is not a set of propositions but a dialogical event, a loving call from God that draws the individual out of isolation and into a relationship of ethical responsibility. He famously assigned complementary roles to Judaism and Christianity in the process of redemption: Judaism, as the “eternal fire,” lives as if redemption is already present within its cyclical liturgical life, while Christianity, as the “eternal rays,” carries the message out into the world. Together, Buber and Rosenzweig reoriented Jewish philosophy toward the primacy of the relational, arguing that truth is not found in solitary contemplation but in the dynamic, lived encounter between the self and the other.

Phenomenology, Hermeneutics, and the Ethical Turn

The mid-20th century witnessed a significant “ethical turn” in Jewish philosophy, deeply influenced by the European traditions of phenomenology and hermeneutics. Phenomenology, the philosophical study of the structures of experience and consciousness pioneered by Edmund Husserl, provided a powerful method for bracketing preconceived notions and attending to the way things appear in lived experience. Jewish thinkers adapted this method to explore the nature of faith, intersubjectivity, and ethical obligation. The most significant figure in this movement was Emmanuel Levinas, a Lithuanian-born French philosopher whose experience as a prisoner of war during the Holocaust profoundly shaped his thought. Levinas used phenomenology to critique the entire tradition of Western ontology, from Plato to his own teacher, Martin Heidegger, for prioritizing the question of Being over the question of the Good. He argued that this focus on Being leads to a “totality” where the Other is reduced to a concept, an object to be known and assimilated into the self’s own world.

In place of this, Levinas proposed that ethics is first philosophy. For him, the fundamental human experience is not the contemplation of Being but the face-to-face encounter with the Other person. The face of the Other is not merely a physical object; it is an epiphany, a trace of the Infinite that commands, “Thou shalt not kill.” This ethical command precedes any choice or contract. It establishes an asymmetrical responsibility, where I am infinitely responsible for the Other, a responsibility that is not reciprocal and cannot be escaped. This radical ethics, which Levinas drew from both phenomenological analysis and the depths of Jewish tradition, places the relationship with the Other at the absolute center of human existence. Concurrently, philosophical hermeneutics—the theory of interpretation—provided Jewish thinkers with sophisticated tools for re-engaging with sacred texts like the Torah and Talmud. Moving beyond literalism or historical criticism, a hermeneutic approach emphasizes the dynamic interplay between the reader and the text, viewing interpretation as a “fusion of horizons” where ancient wisdom is brought into a living dialogue with contemporary concerns. This allowed for a revitalization of Jewish textual study, seeing it not as a static tradition but as an ongoing conversation that continues to generate new meanings and ethical insights.

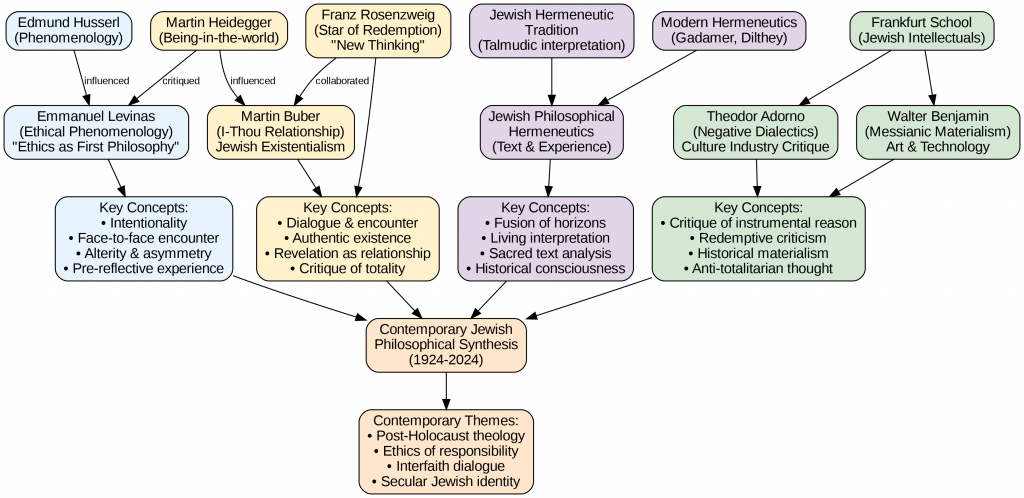

This diagram outlines the core concepts of modern Jewish philosophy, showing the relationships between existential dialogue, phenomenological ethics, and critical theory.

Critical Theory and the Frankfurt School

The Frankfurt School, a group of predominantly Jewish intellectuals associated with the Institute for Social Research, developed a powerful and influential body of thought known as critical theory. Thinkers like Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Walter Benjamin forged a unique synthesis of Marxist social analysis, psychoanalysis, and German philosophy to offer a searing critique of modern capitalist society. Their Jewish background and the direct experience of fleeing Nazi Germany were central to their intellectual project. They sought to understand why the promises of the Enlightenment—reason, freedom, and progress—had culminated in the barbarism of fascism and the Holocaust. In their seminal work, Dialectic of Enlightenment, Horkheimer and Adorno argued that the very instrumental reason that enabled humanity to dominate nature had turned back on itself, leading to new forms of social domination and control. They identified the “culture industry”—the system of mass-produced entertainment in film, radio, and magazines—as a key mechanism for enforcing conformity, pacifying the masses, and extinguishing the capacity for critical thought.

Walter Benjamin, another key associate of the school, blended historical materialism with a unique form of secularized Jewish messianism. He rejected the idea of history as a linear, inevitable march of progress. Instead, he saw history as a series of catastrophes for the oppressed, which could only be redeemed by a “messianic” interruption—a revolutionary moment that would blast open the continuum of history. His famous essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” analyzed how new technologies like photography and film destroyed the traditional “aura” of the artwork, creating the potential for a new, more politicized form of art, though one that could also be co-opted for fascist propaganda. The Frankfurt School’s analysis of antisemitism was particularly trenchant. They saw it not as a mere religious prejudice but as a deeply ingrained pathology of modern society, a projection of repressed fears and a symptom of the failure of reason. Their work represents a profound and often pessimistic attempt to diagnose the ills of modernity from the perspective of its victims, maintaining a fragile hope for emancipation while relentlessly exposing the mechanisms of oppression.

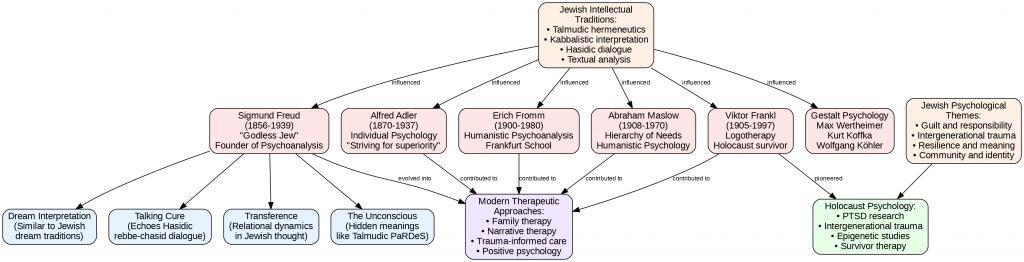

Psychoanalysis and the Jewish Intellectual Tradition

The birth and development of psychoanalysis are inextricably linked to the Jewish intellectual tradition of early 20th-century Vienna. Its founder, Sigmund Freud, was a self-described “godless Jew” whose complex and ambivalent relationship with his heritage profoundly shaped his revolutionary theories of the mind. While Freud insisted that psychoanalysis was a universal science, free from any ethnic or religious affiliation, its core tenets and methods bear the unmistakable imprint of his background. The psychoanalytic emphasis on interpretation, the search for hidden meanings beneath the surface of dreams and slips of the tongue, resonates deeply with the long-standing Jewish hermeneutic tradition of Talmudic and Kabbalistic textual analysis. The therapeutic process itself, often called the “talking cure,” echoes the dialogical nature of study and confession found in certain Jewish practices, such as the relationship between a Hasidic rebbe and his followers. Freud’s own experiences with the pervasive antisemitism of Viennese society informed his theories on repression, group psychology, and the nature of prejudice.

Freud’s intellectual legacy was carried forward by a host of predominantly Jewish thinkers who expanded and revised his theories. Melanie Klein, a pioneer of object relations theory, shifted the focus of psychoanalysis from instinctual drives to the infant’s earliest relationships with caregivers (or “objects”). Her work explored the primitive emotional world of love, hate, envy, and gratitude, providing a framework for understanding the foundations of the psyche. Heinz Kohut, another influential Jewish analyst who fled the Nazis, developed self psychology. He moved away from Freud’s emphasis on guilt and conflict to focus on the development of a healthy, cohesive self. Kohut argued that humans have a fundamental need for empathetic responses from others—what he called “selfobject” experiences—to develop a stable sense of self-worth and vitality. His work offered a more compassionate and humanistic vision of psychoanalysis, one deeply attuned to the wounds of narcissistic injury and the healing power of empathy. These and other Jewish thinkers helped transform psychoanalysis from a theory of instinctual drives into a rich and varied exploration of human relationships, emotional development, and the search for meaning, ensuring its enduring relevance throughout the 20th century and beyond.

Contemporary Challenges and Misconceptions

Despite significant progress in interfaith relations and cultural understanding over the past century, Jewish communities continue to face a range of contemporary challenges, many of which are rooted in long-standing misconceptions and deeply ingrained societal prejudices. The persistence of antisemitic tropes, amplified by the speed and reach of digital media, poses a continuous threat to Jewish safety and well-being. These modern challenges are compounded by significant educational gaps regarding Jewish history and culture among gentile populations, which create fertile ground for stereotypes to take root. Furthermore, media representations often fall short of capturing the diversity and complexity of Jewish life, instead relying on tired caricatures that distort public perception. Addressing these issues requires a clear-eyed analysis of their origins, their psychological impact, and the pathways toward fostering a more informed and respectful public discourse.

The Persistence of Antisemitic Tropes

Antisemitic tropes have demonstrated a remarkable and disturbing persistence in modern society, adapting their form to new contexts while retaining their core prejudicial content. These misconceptions are not random slurs but part of a coherent, albeit false, worldview that casts Jews as a malevolent and conspiratorial force. One of the most enduring and pernicious myths is the conspiracy theory of Jewish world control, famously codified in the fraudulent text The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. This trope manifests today in claims that Jews control global finance, media, and governments, a narrative that serves as a simplistic explanation for complex socioeconomic problems and deflects blame from systemic issues. Another ancient and vicious trope is the blood libel, the medieval accusation that Jews murder non-Jews to use their blood in religious rituals. While seemingly archaic, this myth resurfaces in modern forms, such as in accusations that Israel engages in organ harvesting or commits genocide, drawing on the same underlying theme of Jewish malevolence and inhumanity.

The theological charge of deicide, the claim that Jews are collectively responsible for the death of Jesus, has historically fueled centuries of Christian antisemitism and, despite being officially repudiated by many Christian denominations, continues to subtly inform negative perceptions of Jews. Similarly, the accusation of dual loyalty, which posits that Jewish citizens are more loyal to Israel or a global Jewish collective than to their own countries, is frequently used to question their patriotism and portray them as a disloyal fifth column. The psychological mechanisms behind the persistence of these tropes are powerful. Scapegoating provides a simple target for societal anger and anxiety during times of crisis. The human mind’s attraction to conspiracy theories, which offer a sense of order and explanation in a chaotic world, makes these narratives appealing. Furthermore, in-group/out-group dynamics can be exploited to foster solidarity within a majority group by demonizing a minority “other.” In the 21st century, social media and the internet have become powerful amplifiers for these tropes, allowing them to spread rapidly and reach global audiences, often divorced from historical context and factual rebuttal, ensuring their continued circulation and impact.

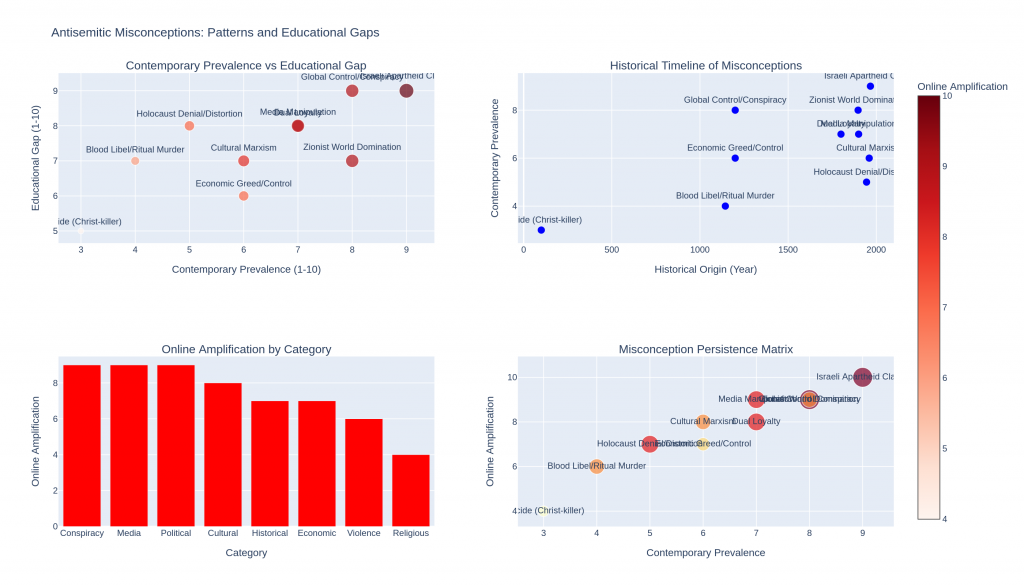

This visual breaks down the structure and evolution of common antisemitic tropes, showing how historical myths are adapted for contemporary contexts.

Educational Gaps and Media Representation

A significant factor contributing to the persistence of antisemitism and misunderstanding is the widespread educational gap concerning Jewish history, culture, and religion among gentile populations. For centuries, historical separation—both imposed and voluntary—limited direct interaction and fostered an environment where ignorance and suspicion could flourish. In many contemporary educational systems, Jewish history is often taught only in the context of the Holocaust, which, while essential, can create a one-dimensional view of Jews solely as victims, obscuring the rich, diverse, and resilient 3,000-year history of Jewish civilization. Key concepts of Jewish culture, the diversity of religious practice from Orthodox to Reform, and the internal debates and intellectual traditions that have shaped Jewish thought are rarely part of standard curricula. This lack of foundational knowledge creates a vacuum that is easily filled by stereotypes and misinformation.

This problem is exacerbated by media representations that frequently perpetuate harmful and simplistic stereotypes. Jewish characters in film and television are often confined to a narrow set of archetypes: the overbearing “Jewish mother,” the neurotic and physically weak intellectual man, the spoiled “Jewish American Princess,” or characters defined by their association with wealth and professions like law or finance. While some portrayals may be intended as humorous or even affectionate, they reinforce a limited and often negative set of associations in the public imagination. A critical issue is the lack of diversity in these representations. The media overwhelmingly portrays Jews as white and Ashkenazi (of European descent), effectively erasing the existence of Jews of Color, as well as Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, who have different cultural histories and experiences. This monolithic portrayal distorts the reality of a global and multiracial Jewish people. In recent years, there have been emerging efforts to create more nuanced, authentic, and diverse portrayals of Jewish life in media. Shows and films that explore the complexities of Jewish identity, faith, and family life without resorting to caricature represent a positive step toward bridging the understanding gap and providing gentile audiences with a more accurate and humanizing window into the Jewish experience.

Christian Misconceptions and Theological Divides

The relationship between Judaism and Christianity, born of a shared heritage but marked by centuries of theological conflict and persecution, remains a site of significant misunderstanding. Many common Christian misconceptions about Judaism are rooted in a historical tendency to view it through a Christian lens, often as a precursor or an incomplete version of Christianity. One prevalent misconception is the portrayal of Judaism as a cold, rigid, and purely legalistic religion, obsessed with rules and rituals, in contrast to a Christian faith supposedly based on love and grace. This caricature, often drawn from polemical readings of the New Testament, ignores the deep spirituality, ethical richness, and emphasis on divine love and justice that are central to Jewish theology and practice. Another common error is to see Judaism as simply “Christianity minus Jesus,” a framework that fails to recognize Judaism as a complete and independent faith with its own distinct theological structure, sacred texts, and understanding of God, humanity, and history.

The core theological differences are profound. The Christian concepts of the Trinity, the incarnation of God in Jesus, and salvation through faith in Jesus’s atoning death are fundamentally incompatible with Judaism’s strict monotheism, which rejects the possibility of a human being deified or an intermediary between God and humanity. While both faiths share the Hebrew Bible (which Christians call the Old Testament), their interpretive approaches diverge completely. Christianity reads these texts through a Christological lens, seeing them as prophecies fulfilled in Jesus. Judaism interprets them through the lens of the Talmud and a long tradition of rabbinic commentary, focusing on their guidance for ethical living and the covenantal relationship between God and the Jewish people. A particularly damaging historical theological concept is supersessionism, or replacement theology—the belief that the Christian Church has replaced Israel (the Jewish people) as God’s chosen people and that the “new” covenant in Christ has made the “old” covenant with the Jews obsolete. This doctrine has been used for centuries to justify antisemitism and deny the ongoing validity of Judaism. In the post-Holocaust era, many Christian denominations have formally rejected supersessionism and have engaged in meaningful interfaith dialogue to address these historical biases, fostering a new era of mutual respect and a deeper, more accurate understanding of Judaism on its own terms.

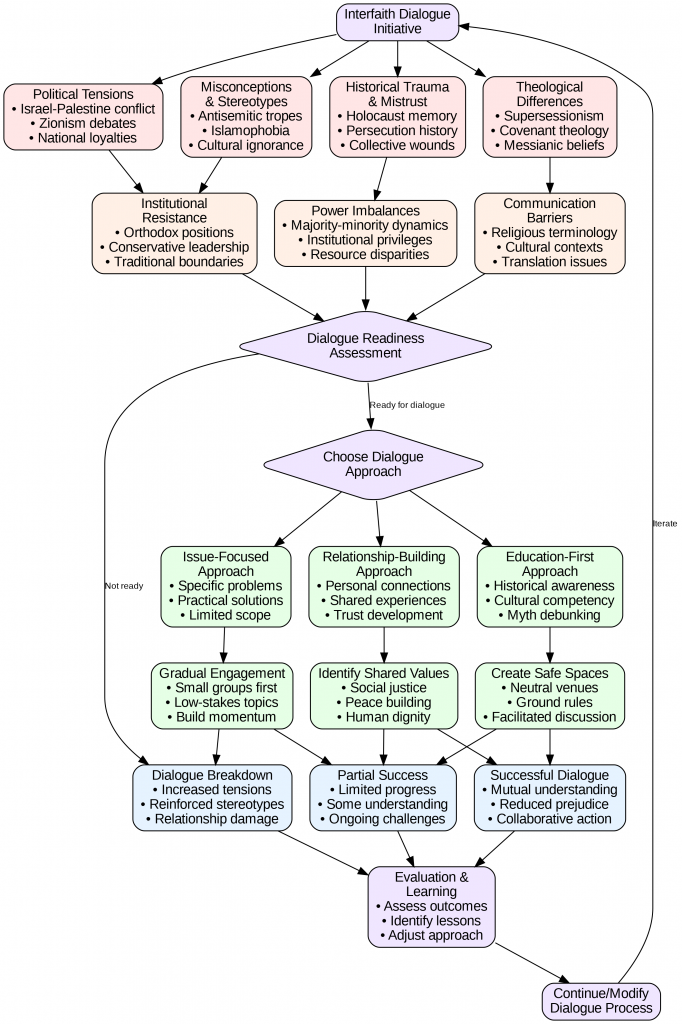

This flowchart maps the essential steps in constructive interfaith dialogue, from identifying misconceptions to achieving mutual understanding and collaborative action.

Synthesis and Conclusion

The century from 1924 to 2024 has been a period of profound transformation for Jewish faith and identity, marked by the depths of human tragedy and the heights of intellectual and spiritual resilience. A modern analysis reveals a people whose psychological landscape has been irrevocably shaped by the trauma of the Holocaust, leading to enduring challenges such as PTSD and intergenerational trauma, yet also fostering remarkable posttraumatic growth and robust mechanisms of communal resilience. The constant negotiation of identity within the diaspora, under the pressures of assimilation and displacement, has forged a dynamic and often hybrid sense of self, one that continually balances particularity with universalism.

Concurrently, this period witnessed an extraordinary flourishing of Jewish philosophical thought. Grappling with the crises of modernity, Jewish thinkers turned to existentialism, phenomenology, and critical theory to forge new understandings of faith, ethics, and existence. From Buber’s philosophy of dialogue and Levinas’s radical ethics of the Other to the Frankfurt School’s trenchant critique of a society that produced Auschwitz, these intellectual movements re-grounded Jewish thought in the concrete realities of lived experience and ethical responsibility. Psychoanalysis, itself a product of the Jewish intellectual milieu of Vienna, provided a new language for understanding the inner world, a tradition continued and expanded by subsequent generations of Jewish thinkers.

Yet, this internal evolution has occurred against a backdrop of persistent external challenges. Ancient antisemitic tropes have proven disturbingly adaptable, finding new life in digital spaces and continuing to fuel prejudice. These misconceptions are sustained by significant educational gaps and media representations that often fail to capture the diversity and complexity of Jewish life. The ongoing work of interfaith dialogue, particularly with Christianity, remains crucial to dismantling theological justifications for prejudice and building a foundation of mutual respect.

In conclusion, the nature of Jewish faith and identity in the modern era is not static but is a dynamic process of becoming, shaped by the interplay of memory, trauma, adaptation, and intellectual innovation. It is a testament to the human capacity to create meaning in the wake of destruction, to question and reinterpret tradition in light of new realities, and to maintain a collective identity across diverse and scattered communities. An objective, scholarly framework for understanding this journey is essential, not only for academic integrity but for fostering a world that can move beyond stereotype and engage with the rich, multifaceted, and ongoing story of the Jewish people.