Symbolic Weakening

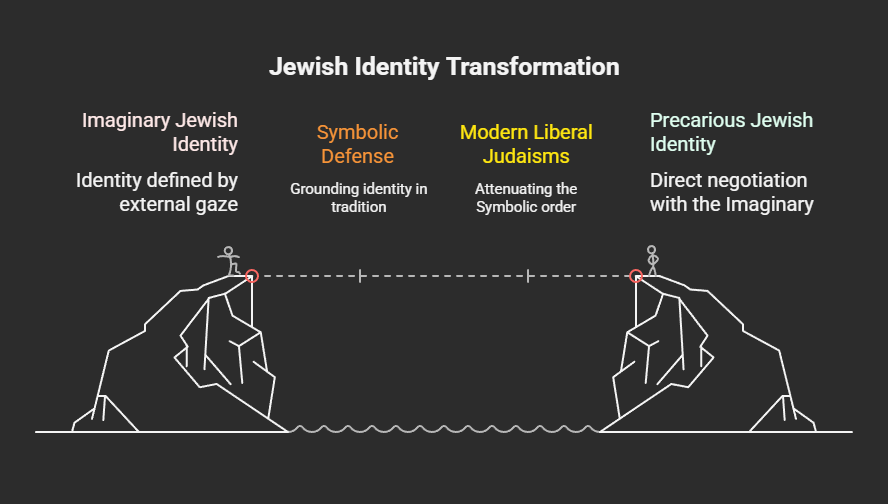

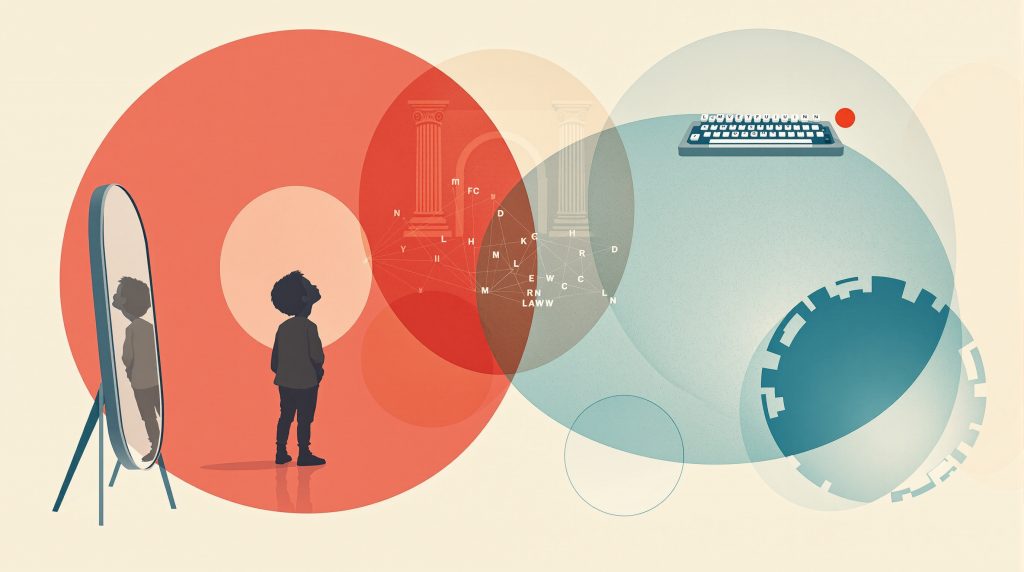

Abstract: This paper applies a synthesis of Lacanian and Jungian psychoanalytic theory to the historical and contemporary dynamics of Jewish identity. It argues that the persistent antisemitic “image of the Jew” functions as a Lacanian Imaginary trap, a specular screen onto which the non-Jewish collective projects its Jungian shadow. This process, which solidifies the non-Jewish ego through a logic of exclusion, is historically counteracted within Judaism by a robust Symbolic order, epitomized by the totalizing legal framework of Halakha and the textual immersion of the yeshiva system. The paper further contends that the theological shifts within Liberal and Reform Judaism—specifically the move from binding law to individual autonomy and the adoption of biblical criticism—constitute a structural attenuation of this Symbolic order. This “thinning” of the Symbolic, it is proposed, may render the modern liberal Jewish subject more susceptible to the definitions and interpellations of the Imaginary, re-centering identity in relation to the gaze of the Other rather than an internally coherent system of signifiers.

Introduction

Jewish identity has been historically constituted through a dialectical struggle between two powerful psychoanalytic registers: an externally imposed Imaginary identity, constructed from the projected Jungian shadow of the non-Jewish Other, and an internally generated Symbolic identity, grounded in the textual and legal traditions of Orthodox Judaism. This paper will posit that the rise of modern liberal Judaisms represents a significant shift in this dynamic, potentially weakening the Symbolic defenses against the Imaginary trap. The analysis will proceed not as a sociological survey but as a theoretical exploration of the psychic structures underpinning both Jewish identity and the persistence of antisemitism.

The theoretical framework deploys concepts from two major schools of psychoanalysis. From Jacques Lacan, it draws upon the distinction between the psychic registers of the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real.1 The Imaginary, the realm of the image and ego-formation, provides the concept of the “trap,” an alienating identification with an external reflection. The Symbolic, the domain of language, law, and culture, offers the concept of a structured defense, an identity grounded in a pre-existing network of signifiers.2 From Carl Jung, the analysis incorporates the concept of the collective shadow—the repository of a society’s repressed and disowned traits—and the psychic mechanism of projection, by which these traits are externalized onto an out-group.4

The paper’s argument unfolds in three parts. The first part, “The Architecture of the Trap,” details the construction of the “Imaginary Jew.” It will demonstrate how the historically-sedimented antisemitic image serves as a screen for the projection of the non-Jewish collective shadow, a process that stabilizes the non-Jewish ego while ensnaring the Jewish subject in an identity defined by the Other’s gaze. The second part, “The Fortress of the Word,” examines the traditional counter-strategy found within Orthodox Judaism. It analyzes the comprehensive legal system of Halakha and the immersive textual environment of the yeshiva as a powerful, totalizing Symbolic order that insulates the subject from the Imaginary by grounding identity in law and language. The third and final part, “The Thinning of the Symbolic,” investigates the psycho-structural impact of the theological evolution within Liberal and Reform Judaism. It argues that the principled moves toward individual autonomy and the adoption of biblical criticism, while central to their modernizing project, function structurally to attenuate the Symbolic order, leaving the liberal Jewish subject in a more precarious and direct negotiation with the Imaginary. This inquiry is framed by Lacan’s own assertions that racism is rooted in a rejection of the Other’s unique mode of enjoyment, or jouissance, and that the historical segregation of the Jews serves as a chilling model for future forms of scientifically and universally justified exclusion.5

Part I: The Architecture of the Trap: The Imaginary and the Projected Shadow

This section establishes the theoretical mechanism by which the “image of the Jew” is constructed and functions as a psychic trap. It synthesizes Lacanian and Jungian concepts to demonstrate how an external social phenomenon—antisemitism—operates at the deepest levels of ego-formation for both the perpetrator and the victim of the projective gaze.

The Mirror of the Other: Ego-Formation in the Lacanian Imaginary

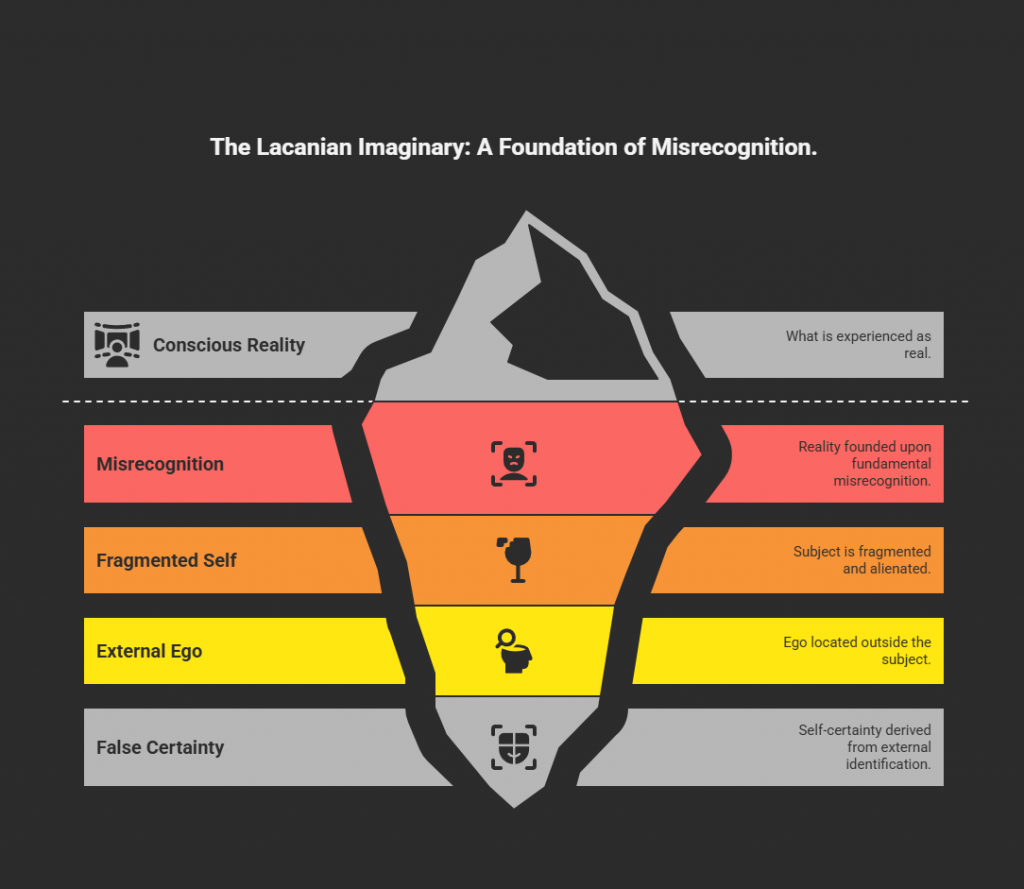

The Lacanian Imaginary is the register of images, identification, and the ego. It is not the realm of the “imaginary” in the sense of fantasy, but rather the very structure of what is experienced as conscious reality.2 This reality, however, is founded upon a fundamental misrecognition (méconnaissance). The Imaginary is a realm of “necessary fictions” that provide a sense of coherence and unity to a subject who is, in actuality, fragmented and alienated.2

The foundational drama of the Imaginary is the Mirror Stage, which Lacan describes as a critical developmental moment between six and eighteen months.1 The infant, who experiences its own body as a collection of uncoordinated motor impulses and fragmented sensations—an “insufficiency”—perceives its reflection in the mirror as a unified, coherent gestalt.2 This specular image represents an “anticipation” of mastery and wholeness that the infant has not yet achieved. The infant’s jubilant recognition of this image is the moment of ego-formation. However, this identification is profoundly alienating. The coherent, unified self—the ego, or moi—is located outside the subject, in the external imago.8 The ego is thus, from its very inception, an objectification, a “mirage of spatial identification” that masks the subject’s internal fragmentation.1

This process of alienation is constitutive of the subject’s reality. The “self-certainty” of the ego is derived from this identification with an external object, but it is a false certainty, a defense mechanism against the underlying experience of the “fragmented body”.1 The Imaginary, therefore, is a perpetual dynamic of misrecognizing oneself in an other, creating a fundamental disjunction or gap within the subject that can never be fully overcome.1 The ego is forever caught in a dialectic of identification with an external image, a process that defines its relationship to the world and to other subjects, who are also perceived as unified images.

The Scapegoat Mechanism: Jung’s Collective Shadow and Projection

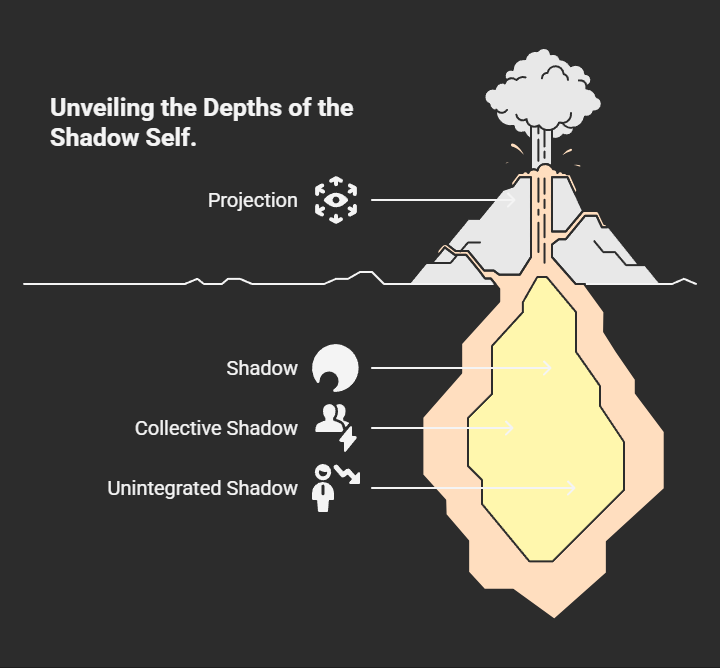

Parallel to the Lacanian ego’s reliance on an external image, the Jungian ego relies on an external “other” to manage its internal conflicts. For Carl Jung, the shadow represents the “dark side” of the personality, the unconscious repository of all the primitive, negative, and socially unacceptable impulses that the conscious ego and its idealized self-image, the persona, choose to reject and repress.4 These disowned parts can include egotism, greed, unacceptable desires, and aggression.4 To become conscious of one’s shadow is a profound moral undertaking, as it “challenges the whole ego-personality” and requires a “considerable moral effort” to recognize these dark aspects as real and present within oneself.9

The shadow is not merely a personal phenomenon. Jung posited the existence of a collective shadow, an archetype comprising the darker aspects of an entire society, culture, or nation that are collectively disowned and repressed.4 This collective shadow is ancestral and is carried in the collective unconscious; it materializes historically in phenomena like xenophobia, dehumanization, and war.4 When a group or nation fails to consciously integrate its collective shadow, it inevitably resorts to the defense mechanism of projection.

Projection is the psychic process whereby the ego externalizes its own unacknowledged and undesirable qualities, attributing them to another person or group.4 This mechanism serves to protect the ego’s idealized self-image by locating evil, corruption, and inferiority outside of itself. As Jung noted, while we find it difficult to see our own shadow, we are adept at spotting it in others.9 A person “possessed by his shadow is always standing in his own light and falling into his own traps”.4 On a collective scale, this dynamic is dangerously powerful. Unscrupulous political leaders can exploit this mechanism by providing the populace with a designated scapegoat—an out-group onto which the collective shadow can be projected. Adolf Hitler’s systematic designation of the Jewish population as “subhumans” (Untermenschen) is the paradigmatic example of a leader inciting an entire nation to project its shadow, thereby justifying persecution and violence.11

Constructing “The Jew”: The Imaginary Screen for the Collective Shadow

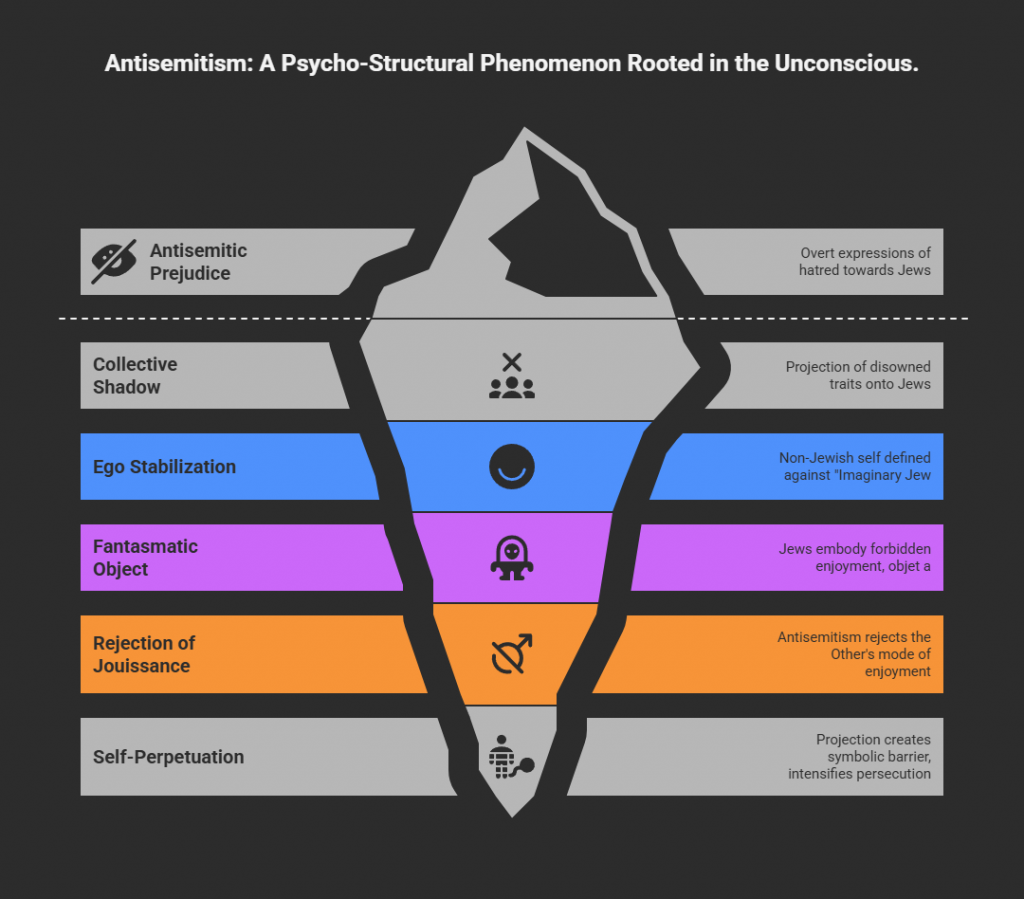

The synthesis of these Lacanian and Jungian frameworks reveals the psycho-structural function of antisemitism. The historically and culturally constructed “image of the Jew” operates as the ideal Lacanian imago—a stable, external image—that serves as the perfect screen for the projection of the Western/Christian collective Jungian shadow. This process is not merely an incidental prejudice; it is a core mechanism for the stabilization of the non-Jewish collective ego. The non-Jewish self is constituted, in part, by its opposition to this fantasmatic, Imaginary Jew.

The content of this imago has been built up over centuries, creating a readily available cultural shorthand for everything the dominant culture wishes to disown. This includes a vast array of physical stereotypes, such as the exaggerated “Jewish nose,” designed to signify racial otherness and moral degeneracy.13 It encompasses a host of behavioral stereotypes: the Jew as greedy, miserly, and a financial manipulator, a trope originating in the Middle Ages when Jews were forced into money-lending 13; and the Jew as a conspiratorial power, plotting world domination as detailed in forgeries like

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.14 Finally, it is saturated with theological and demonic associations, portraying Jews as being in league with the devil, as the perpetrators of deicide, and as murderers of Christian children for ritual purposes (the blood libel).16 This dense network of images, disseminated through art, folklore, political cartoons, and propaganda, forms a coherent and powerful imago in the collective Imaginary.15

This analysis can be deepened by introducing a more advanced Lacanian concept: the fantasmatic object, or objet petit a. The “image of the Jew” is more than just a collection of negative traits; it functions as the embodiment of the objet a—the object-cause of desire and, crucially, the fantasized locus of the Other’s forbidden enjoyment, or jouissance. Lacanian analyses of Nazism suggest that the ultimate goal of the Holocaust was not simply the extermination of empirical Jewish people but a perverse attempt to force the revelation of a horrifying, sublime substance—”what is in a jew more than a jew”.19 The concentration camp, in this reading, becomes a grotesque “assembly line that tries to produce this object a” through ritualized humiliation and murder.19 This connects directly to Lacan’s theory that racism is fundamentally a “rejection of the jouissance of the Other”.5 The antisemite fantasizes that the Jew possesses a secret, excessive mode of enjoyment—related to money, arcane knowledge, or a direct line to a vengeful God—that is inaccessible to the self. This makes the “image of the Jew” simultaneously an object of repulsion and intense, envious fascination.

The structural necessity of this antisemitic imago for the formation of the Western/Christian collective ego becomes clear. The ego, in both psychoanalytic schools, requires an “Other” for its definition.1 The culturally saturated antisemitic stereotype serves this dual function perfectly. By projecting its collective shadow—greed, materialism, lust for power, clannishness, rootlessness—onto this stable imago, the non-Jewish collective ego can constitute itself as its virtuous opposite: generous, spiritual, moral, loyal, and rooted. Antisemitism, therefore, is not merely an attitude about Jews; it is a fundamental psychic strategy for the construction of the non-Jewish self. The Imaginary “trap” for Judaism is the necessary and tragic byproduct of the Other’s own ego-maintenance project.

This trap is, by its nature, self-perpetuating. The act of projection insulates and deludes the projector, creating a symbolic barrier between their ego and the Real.4 The more the antisemite fails to find empirical proof of the fantasmatic Jew, the more they intensify their persecution, convinced that the horrifying substance (objet a) is being cleverly hidden.19 This dynamic places the Jewish subject in a psychoanalytic double bind. Any response is pre-interpreted by the Other’s fantasy: assimilation is seen as deception, resistance as aggression, self-isolation as proof of clannishness, and economic success as evidence of conspiracy. The Jewish subject is thus trapped within the logic of the Other’s Imaginary, where their very existence and reactions serve only to confirm the original projection.7

Part II: The Fortress of the Word: Orthodox Judaism and the Symbolic Order

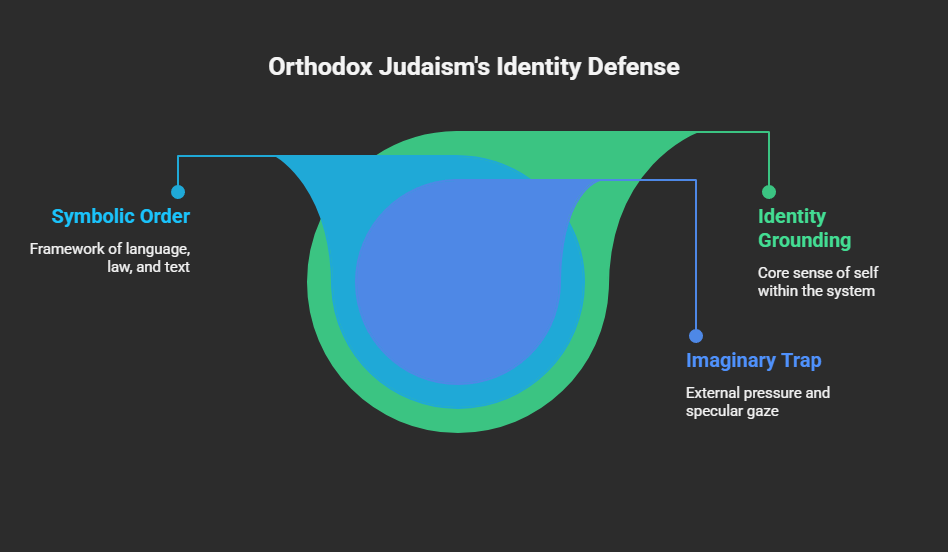

In the face of the relentless pressure of the Imaginary trap, traditional Judaism developed a powerful and sophisticated defense mechanism. This defense is not primarily psychological in the modern sense but structural, rooted in what Lacan termed the Symbolic order. By creating a totalizing internal world of language, law, and text, Orthodox Judaism provided a means for the subject to ground their identity in a system that transcends and resists the external, specular gaze of the Other.

Beyond the Image: The Subject of the Symbolic Order

The Symbolic is the register of language, law, kinship structures, and social convention—the “signifying order” that pre-exists the individual and into which the subject must be inserted.1 It is the realm of the “big Other,” which Lacan defines not as another person but as the trans-individual treasury of signifiers that structures reality and the unconscious.2 The unconscious, for Lacan, is “structured like a language,” a complex network of signifiers rather than a repository of primal instincts.2

Entry into the Symbolic order is what allows the subject to move beyond the Imaginary ego (moi) and become a speaking subject (je). This process is inherently fragmenting. The illusory unity of the mirror stage is shattered by the demands of language, which introduces lack and difference into the subject’s world.1 The subject of the Symbolic is a “split subject” ($), who can never be fully represented in language and must find their identity by navigating the pre-existing chain of signifiers. This marks a crucial shift from an identity based on a static, external image to an identity based on one’s position within a dynamic linguistic and legal structure.

The Law is the central pillar of the Symbolic order. It functions to regulate desire and structure social relations.3 In the Oedipal drama, the “Name-of-the-Father” serves as the master signifier that represents this Law. It is the paternal metaphor that breaks the infant’s Imaginary, dyadic fusion with the mother and inserts the child into the wider social and linguistic world.3 In a religious framework, the Law of God, as revealed in sacred texts, functions as this ultimate structuring principle, providing the “paternal metaphor” that quilts the entire symbolic universe with meaning and prohibits the slide into psychosis or the stasis of the Imaginary.3

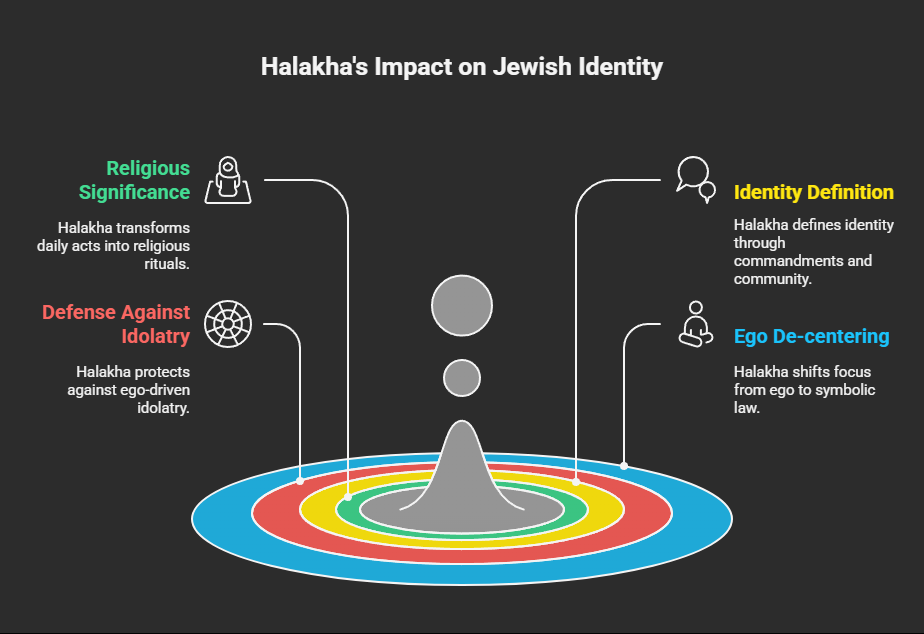

Halakha as a Totalizing Symbolic Framework

Orthodox Judaism’s primary expression of this Symbolic order is Halakha. Often translated as “Jewish Law,” its Hebrew root more accurately means “the path that one walks”.23 It is not merely a collection of ritual prohibitions but a comprehensive, all-encompassing system for living that governs every conceivable aspect of existence. From the moment of waking to the moment of sleep, from dietary laws (kashrut) to business ethics, from modes of dress to the structure of time (the Sabbath and festivals), Halakha provides a detailed script for life.25 For Orthodox Judaism, this system is not a human invention but is of divine origin, derived from the Written Torah and the Oral Law, both believed to have been given to Moses at Sinai.25

The power of Halakha as a Symbolic system lies in its ability to constantly inscribe the subject’s body and daily life with the signifiers of the covenant. By turning the most mundane acts—eating, dressing, speaking—into acts of religious significance, it transforms the entirety of lived experience into a text.23 This creates what has been termed a “thick” religious life, a robust and meaningful structure that integrates the Torah’s symbolic matrix into every moment.28 The Halakhic subject is thus continuously defined and re-defined not by how the external world sees them, but by their relationship to the 613 commandments (mitzvot) and their position within the covenantal community of Israel. This provides a complete, internally coherent framework for identity that functions as a powerful counter-gaze to the hostile projections of the non-Jewish world.

This rigorous, non-visual, and abstract nature of Halakhic Judaism can be understood as a structural defense against the primary danger of the Imaginary: idolatry, the worship of the image. Lacan interprets the biblical prohibition of graven images not merely as a religious rule but as a psychoanalytic injunction against the ego’s narcissistic desire for a perfect, whole reflection of itself. The idol is the ultimate specular image, a materialization of the ego’s fantasy of being its own autonomous master.22 Orthodox Judaism’s aniconic tradition and its profound emphasis on law over image, text over personality, is a theological manifestation of this anti-idolatrous principle.

Halakha, by structuring life around abstract rules and textual interpretations rather than visual representations or charismatic figures, functions as a psycho-spiritual technology for de-centering the ego from the Imaginary register. It is a constant practice of choosing the Symbolic Law over the seductive Imaginary image.

The Yeshiva: Forging Identity in the Chain of Signifiers

If Halakha is the software of the Jewish Symbolic order, the yeshiva is the hardware—the primary institution for its transmission and perpetuation.29 The curriculum of the traditional yeshiva is focused almost exclusively on Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and its vast corpus of legal and narrative commentary.29 The goal is not simply to impart information but to mold the student’s entire mode of thought, to initiate them into a specific way of being in the world.

The pedagogical method is central to this process. The practice of chavrusa, or partner study, is a dialogic, often fiercely argumentative immersion into what is known as the “sea of Talmud”.29 It is the antithesis of passive reception. Two students grapple with a text, dissecting its logic, questioning its premises, and marshaling arguments from across the entire rabbinic tradition to support their interpretations. This process forces the student to locate their own subjective position within a multi-vocal, centuries-long conversation. It is an education in grounding one’s identity in the “letter” and the “Word,” not in the image.33 Lacan himself drew a parallel between the psychoanalytic project and a Hebraic tradition that privileges the enigmatic power of the letter and the relentless questioning of received knowledge.33 The yeshiva student becomes a subject of the text, their consciousness and identity shaped by its intricate legal and narrative structures.

The very structure of the Talmud mirrors Lacan’s conception of the unconscious as a “discourse of the Other.” The typical Talmudic page is not a linear text but a complex visual field: a central legal ruling (the Mishnah) is surrounded by layers of commentary and debate (the Gemara), which are themselves flanked by medieval commentaries (like those of Rashi and the Tosafists) that often contradict one another and open up new avenues of inquiry.31 To study Talmud is to immerse oneself in a system where meaning is not fixed or final but is generated through the endless interplay of signifiers. This process habituates the subject to an identity that is not a stable, essential self but a fluid position within a linguistic discourse. This mirrors the Lacanian split subject ($), who is perpetually represented by one signifier for another. The yeshiva student learns, structurally, to be a subject of the text, comfortable with ambiguity, contradiction, and the ultimate lack of a final, totalizing image of truth. This textual subjectivity is the ultimate defense against the simplistic, totalizing, and deadly image projected from the outside.

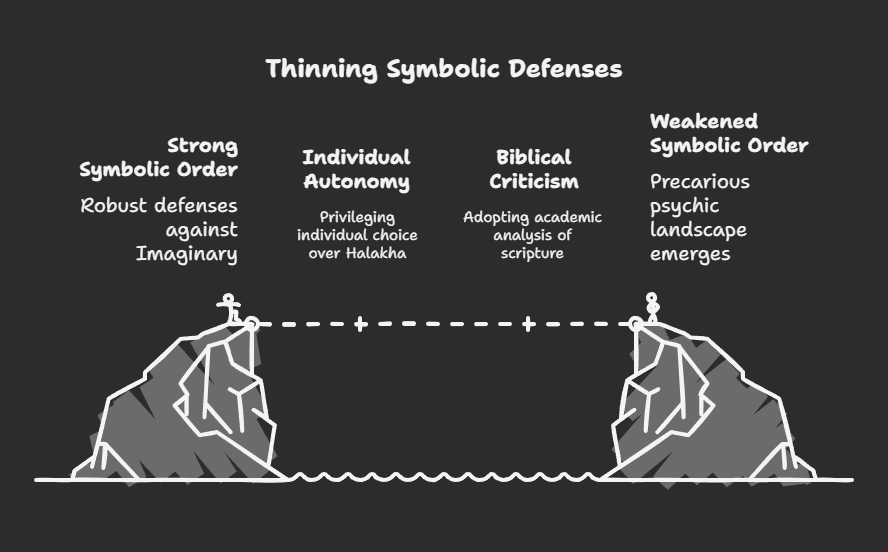

Part III: The Thinning of the Symbolic: Modernity and the Liberal Jewish Subject

The emergence of Liberal and Reform Judaism in the modern era represents a profound theological and sociological shift. Analyzed through a psycho-structural lens, this evolution can be understood as a “thinning” or attenuation of the traditional Symbolic order. This section will argue that these movements’ foundational principles—the privileging of individual autonomy over the authority of Halakha and the adoption of academic biblical criticism—while necessary adaptations to modernity, have the structural effect of weakening the Symbolic defenses against the Imaginary, creating a new and more precarious psychic landscape for the modern Jewish subject.

Autonomy over Authority: The Reform Rupture with Halakha

The Reform movement was born in 19th-century Germany as a direct response to the Jewish Emancipation.36 With the dismantling of ghettos and the granting of civil rights, Jews were faced with the challenge of integrating into modern European society. Early reformers sought to adapt Judaism to this new context by de-emphasizing the ritual practices and laws that set Jews apart, such as the dietary codes (kashrut) and distinctive modes of dress, which were seen as obstructing social and professional progress.36

This practical adaptation was rooted in a fundamental theological shift. The core principle of Jewish life moved from submission to the binding, divine authority of Halakha to the celebration of individual autonomy and informed choice.39 The 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, a foundational document of American Reform Judaism, explicitly stated that only the “moral laws” of the Torah remain binding, while rejecting all ritual laws “such as are not adapted to the views and habits of modern civilization”.37 This position effectively declares that the vast body of rabbinic law is no longer normative.25

In recent decades, the Reform movement has shown a renewed interest in engaging with traditional practices and the literature of Halakha. However, the nature of this engagement is structurally different from that of Orthodoxy. Halakha is approached not as a set of immutable, binding rules but as a “discourse, an ongoing conversation” from which the individual can draw inspiration and guidance.43 Rabbinic responsa (teshuvot) issued by Reform bodies are explicitly “advisory, not authoritative”.43 This transformation is crucial from a Lacanian perspective. The Law is no longer the unyielding, external structure of the “big Other” that constitutes the subject. Instead, it becomes a resource, a heritage to be consulted by a pre-existing, autonomous ego who is the ultimate arbiter of their own religious practice. The vertical axis of authority is replaced by a horizontal one of personal meaning.

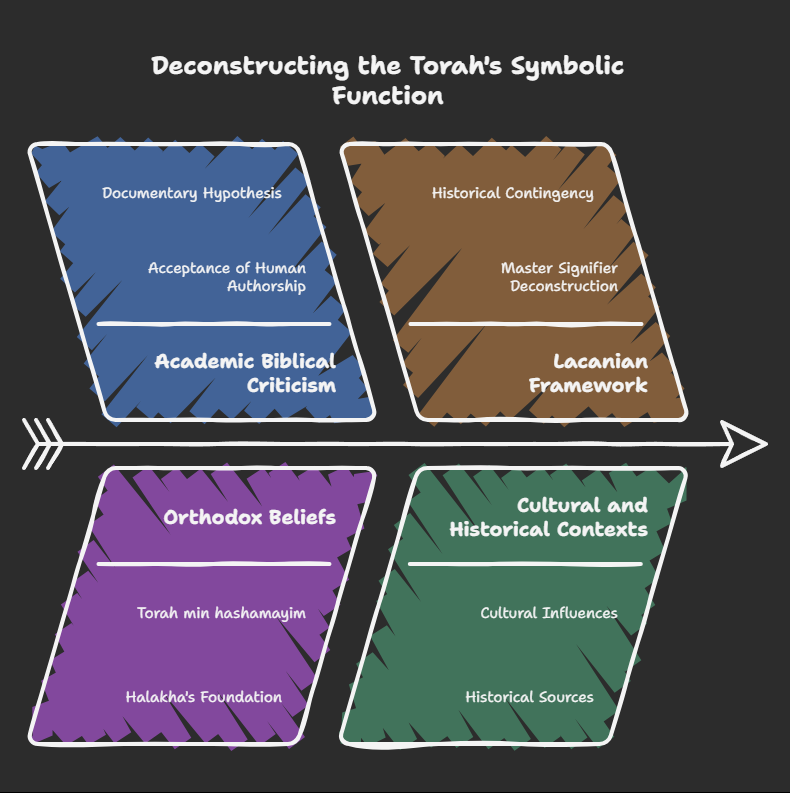

From Divine Word to Human Text: Biblical Criticism and the Symbolic Status of Torah

A second, equally significant structural change within Liberal and Reform Judaism is the acceptance of academic biblical criticism. While liberal theology maintains that the Torah is a divinely inspired text, it also accepts the scholarly consensus that it was written and edited by human hands over many centuries, reflecting the language, culture, and political contexts of its various authors.39 This stands in stark contrast to the Orthodox principle of Torah min hashamayim (Torah from Heaven), which holds that the Pentateuch is a perfect, unitary text dictated verbatim by God to Moses.44

The adoption of source criticism, particularly the Documentary Hypothesis (which posits at least four major authorial strands: J, E, P, and D), has profound implications for the Torah’s symbolic function.45 It reveals the sacred text to be a composite work, replete with internal contradictions, stylistic shifts, and multiple editorial layers.45 This critical approach directly undermines the traditional foundation of Halakha, which often derives complex legal principles from minute textual details, repetitions, or seeming redundancies, all under the assumption of a single, perfect, divine author whose every letter is meaningful.47

In Lacanian terms, the Torah within the Orthodox framework functions as the ultimate Master Signifier (S1). It is the “quilting point” (point de capiton) that anchors the entire chain of meaning in the Jewish Symbolic order, guaranteeing its coherence and authority.3 Biblical criticism effectively deconstructs this Master Signifier. It demonstrates that the S1 (the Torah text) is not a primordial given but is itself a product of a network of other, prior signifiers (S2)—the historical sources, cultural influences, and theological agendas of its human authors. This act of historicizing and deconstructing the foundational text destabilizes the entire symbolic edifice that rests upon it, transforming it from an absolute anchor of meaning into a historically contingent cultural artifact.

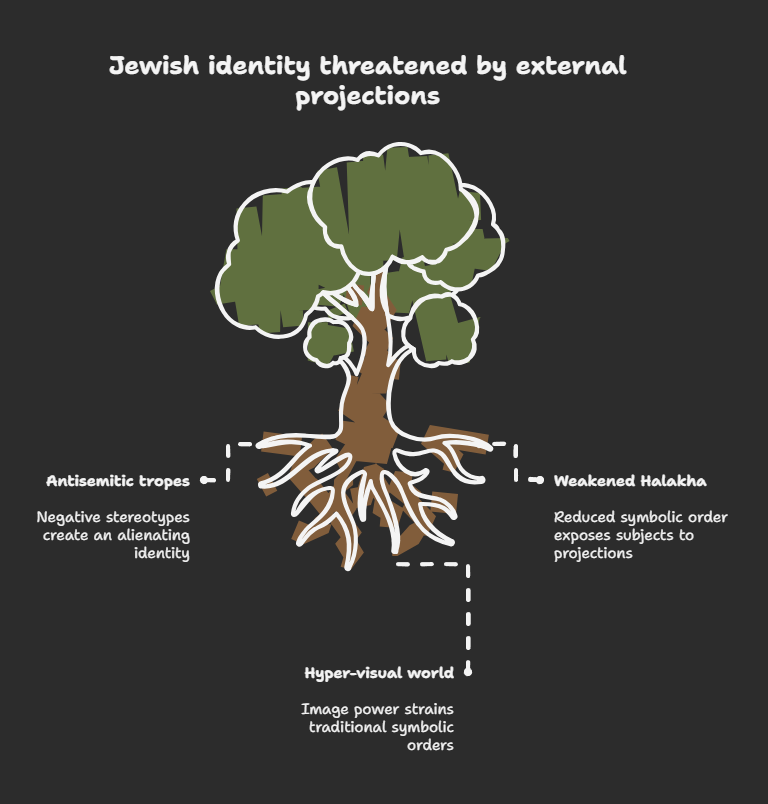

The Subject in the Gaze: Potential Consequences of a Weakened Symbolic

The combined effect of rendering Halakha non-binding and revealing the Torah as a human composite is the creation of a psycho-structural vacuum. The traditional Symbolic order, which once provided a totalizing, internally-generated, and all-encompassing definition of the Jewish subject, loses its absolute structuring force. This does not mean that identity is lost, but that it must be grounded elsewhere. When the internal Symbolic framework is “thinned,” the subject must, by necessity, look increasingly to the Imaginary register for the cues and images that constitute identity.

This increased reliance on the Imaginary can manifest in several ways. First, identity can be sought through social integration and assimilation, a primary goal of early Reform Judaism.36 In this model, the “mirror” for the Jewish self becomes the norms, values, and aesthetics of the dominant non-Jewish culture. Success is measured by the degree to which the reflection in that mirror is harmonious and indistinguishable from its surroundings. Second, identity can be forged through reactive opposition to the antisemitic imago. This often involves centering Jewish identity on fighting antisemitism or making Holocaust remembrance its central pillar.49 While politically and ethically vital, this mode of identification still allows the hostile gaze of the Other to set the terms of the debate and define the contours of the self, albeit in a negative image. Third, identity can be defined primarily as a matter of “culture” or “ancestry,” a common self-perception among non-Orthodox American Jews.49 In Lacanian terms, this represents a significant shift from a Symbolic identity, defined by one’s relationship to Law and Text, to an identity that is more easily captured by Imaginary signifiers: cultural artifacts, ethnic foods, a “feeling” of belonging, or a connection to the State of Israel as a visual and political signifier.

This analysis does not imply a value judgment but rather a structural description. The liberal Jewish project can be seen as a courageous confrontation with what Lacan termed the “lack in the Other.” Lacanian theory posits that the “big Other”—the Symbolic order—is not, in fact, whole or consistent; it is ultimately founded on a void, a lack of ultimate guarantee.34 Orthodoxy’s insistence on the perfection of the Torah and the absolute authority of Halakha can be understood as a powerful and highly functional defense mechanism that papers over this structural lack. By embracing biblical criticism and rejecting absolute authority, Liberal Judaism effectively exposes the “holes” and contradictions within the Symbolic order.45 This forces the subject into a position of greater existential anxiety but also greater responsibility. The subject can no longer rely on the Other to guarantee their identity; they must actively construct it for themselves. This is a potentially more mature, though psychologically more precarious, position.

This precarity is evident in the central role of Tikkun Olam (repairing the world) in contemporary Reform Judaism.50 With the vertical, God-to-human axis of the Symbolic (binding Halakha) attenuated, the horizontal, human-to-human axis of social justice becomes a primary vehicle for Jewish identity.42 This provides a powerful and ethically compelling basis for modern Jewish life. However, the realm of political and social action is deeply embedded in the Imaginary register. It involves images, media, public perception, identification with causes and groups, and often, an antagonistic “us vs. them” logic. Without the grounding of a distinct and robust internal Symbolic order, a Jewish identity based primarily on universalist social justice risks dissolving its unique particularity. It becomes vulnerable to being validated primarily by the gaze of the (liberal, non-Jewish) Other, thus falling back into a different, more subtle, but no less powerful, version of the Imaginary trap.

Conclusion: The Unceasing Dialectic

This analysis has traced a central dialectic in the psychic life of Jewish identity: the perpetual tension between an externally imposed Imaginary construction and an internally generated Symbolic one. The “image of the Jew,” a composite of centuries of antisemitic tropes, functions as a Lacanian Imaginary trap. It serves as a specular screen onto which the non-Jewish collective projects its Jungian shadow, a mechanism that helps solidify the non-Jewish ego at the expense of the Jewish subject, who is ensnared in an alienating identity defined by the Other’s fantasmatic gaze. Historically, the primary defense against this trap has been the robust and totalizing Symbolic order of Orthodox Judaism. The all-encompassing legal framework of Halakha and the immersive textual world of the yeshiva work in concert to forge a subject whose identity is grounded not in the image, but in the Word—in a dense, internally coherent system of law, language, and interpretation.

The theological evolution of Liberal and Reform Judaism in the modern era has fundamentally reconfigured this dynamic. The principled moves to replace the binding authority of Halakha with individual autonomy and to supplant the notion of a perfect, divine Torah with the findings of historical-critical scholarship constitute a structural attenuation of this traditional Symbolic order. This “thinning” of the Symbolic, while a necessary component of Judaism’s engagement with modernity, creates new psychic challenges. It potentially leaves the modern liberal Jewish subject more exposed to the pressures of the Imaginary, compelling them to seek identity in the mirrors of social integration, reactive opposition, or cultural affiliation—all realms where the gaze of the Other remains powerfully operative.

The contemporary situation, in a hyper-visual, secularized, and globalized world, amplifies these dynamics. The power of the image, the logic of the spectacle, and the speed of social media—all phenomena of the Imaginary—are arguably at their zenith, while all traditional Symbolic orders, religious and secular, are under increasing strain. The tension between the Imaginary and the Symbolic, therefore, is not a historical problem to be solved but the fundamental and ongoing condition of modern Jewish existence. The ancient Jewish “struggle with God,” as described in the biblical narrative of Jacob becoming Israel 51, can be re-read through this psychoanalytic lens. It is the subject’s perpetual and necessary negotiation between the alienating, simplifying image reflected in the mirror of the Other, and the demanding, fragmenting, yet ultimately identity-giving call of the Symbolic Law.

Works cited

- The Imaginary and Symbolic of Jacques Lacan – DOCS@RWU, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://docs.rwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=saahp_fp

- Jacques Lacan: Explaining the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the …, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.thecollector.com/jacques-lacan-imaginary-symbolic-real/

- The Symbolic – Wikipedia, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Symbolic

- Shadow (psychology) – Wikipedia, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shadow_(psychology)

- THE JEW, THE WOMAN AND THE … – SciELO Brasil, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.scielo.br/j/agora/a/VtcntKTBPBVM7gyLBnDtH8Q/?lang=en

- THE JEW, THE WOMAN AND THE PSYCHOANALYST: A MODEL OF NON-SEGREGATIVE SOCIAL BOND – Redalyc, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.redalyc.org/journal/3765/376565652002/html/

- Jacques Lacan (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy), accessed on September 22, 2025, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/lacan/

- (PDF) The Imaginary and Symbolic of Jacques Lacan – ResearchGate, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336242295_The_Imaginary_and_Symbolic_of_Jacques_Lacan

- Shadow Self and Carl Jung: The Ultimate Guide to the Human Dark …, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.highexistence.com/carl-jung-shadow-guide-unconscious/

- Shadow Work Guide: 5 Practical Beginner Exercises (Jungian) – Scott Jeffrey, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://scottjeffrey.com/shadow-work/

- C.G. Jung. The Shadow – CHMC Dubai German Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychology Care, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://chmc-dubai.com/articles/c-g-jung-the-shadow/

- Embracing The Shadow – Carl Jung – Orion Philosophy, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://orionphilosophy.com/the-shadow-carl-jung/

- Stereotypes of Jews – Wikipedia, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereotypes_of_Jews

- SUMMARY OF ANTISEMITISM – Echoes & Reflections, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://echoesandreflections.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/02-01-09_StudentHandout_Summary-Antisemitism.pdf

- ANTISEMITIC IMAGERY AND CARICATURES, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://antisemitism.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Antisemitic-imagery-May-2020.pdf

- Why the Jews: History of Antisemitism – United States Holocaust …, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.ushmm.org/antisemitism/what-is-antisemitism/why-the-jews-history-of-antisemitism

- Antisemitism: A Historical Survey – Museum of Tolerance, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.museumoftolerance.com/education/teacher-resources/holocaust-resources/antisemitism-a-historical-survey.html

- 500 Years of Antisemitic Propaganda – United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.ushmm.org/collections/the-museums-collections/collections-highlights/500-years-of-antisemitic-propaganda

- Sacrifice to a dark God: Lacan on nazism | by Psychotic’s guide to memes – Medium, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://medium.com/@akineo/sacrifice-to-a-dark-god-lacan-on-nazism-c328b34e3a73

- The Relationship of Ego & Shadow in C.G. Jung’s Psychology | by J G Johnston – Medium, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://medium.com/@jgjohnston/the-relationship-of-ego-shadow-in-c-g-jungs-psychology-39aea31190c8

- The Subject of Religion: Lacan and the Ten Commandments – SciSpace, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://scispace.com/pdf/the-subject-of-religion-lacan-and-the-ten-commandments-1jiuq7rkga.pdf

- Radical Transcendence: Lacan on the Sinai, accessed on September 22, 2025, http://www.teof.uni-lj.si/uploads/File/BV/BV2017/03/Welten.pdf

- Halakhah: Jewish Law – Judaism 101 (JewFAQ), accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.jewfaq.org/jewish_law

- Halakhah – Jewish Virtual Library, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/halakhah

- Halakha – Wikipedia, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halakha

- Orthodox Judaism | Halakha, Torah, Talmud | Britannica, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Orthodox-Judaism

- Understanding Halacha Rulings: Jewish Law Explained – Scripture Analysis, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.scriptureanalysis.com/understanding-halacha-rulings-jewish-law-explained/

- Pride in our Yeshiva Day Schools | Jonathan Muskat – The Blogs – The Times of Israel, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/pride-in-our-yeshiva-day-schools/

- Yeshiva – Wikipedia, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yeshiva

- Why I Choose A Yeshiva Education For My Children – Lubavitch.com, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.lubavitch.com/why-i-choose-a-yeshiva-education-for-my-children/

- A way of life. Why is the Talmud important to Jews? – Żydowski Instytut Historyczny, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.jhi.pl/en/articles/a-way-of-life-why-is-the-talmud-important-to-jews,4785

- 5 Reasons to Spend a Semester in Yeshiva – Chabad.org, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/1729699/jewish/5-Reasons-to-Spend-a-Semester-in-Yeshiva.htm

- Lacan and the Jews – Association Lacanienne Internationale, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.freud-lacan.com/documents-ged/lacan-and-the-jews/

- “Freud’s Jewish Science and Lacan’s Sinthome” by David Metzger – ODU Digital Commons, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_fac_pubs/16/

- Freud’s Jewish Science and Lacan’s Sinthome – ODU Digital Commons, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=english_fac_pubs

- Reform Judaism | History, Beliefs & Practices – Britannica, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Reform-Judaism

- The Origins of Reform Judaism – Jewish Virtual Library, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-origins-of-reform-judaism

- History of the Reform Movement – My Jewish Learning, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/reform-judaism/

- Reform Judaism – Wikipedia, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reform_Judaism

- The Tenets of Reform Judaism – Jewish Virtual Library, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-tenets-of-reform-judaism

- Halakhah, Responsa, and Reform Judaism – UJR-AmLat, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://ujr-amlat.org/art/en/halakhah-responsa-and-reform-judaism/

- Our History | Roots of Reform Judaism, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.rootsofreformjudaism.org/ourhistory

- Reform Judaism & Halakhah – My Jewish Learning, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/reform-judaism-halakhah/

- Orthodox Judaism and the Impossibility of Biblical Criticism – The Lehrhaus, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://thelehrhaus.com/scholarship/orthodox-judaism-and-the-impossibility-of-biblical-criticism/

- Is it Permissible to Study Biblical Criticism? – The Schechter Institutes, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://schechter.edu/is-it-permissible-to-study-biblical-criticism/

- The Irreconcilability of Judaism and Modern Biblical Scholarship – BYU ScholarsArchive, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1057&context=sba

- A Maimonidean Perspective on Biblical Criticism – Torah Musings, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.torahmusings.com/2014/09/a-maimonidean-perspective-on-biblical-criticism/

- Jews, Law and Identity Politics, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://law.utexas.edu/faculty/wforbath/papers/forbath_jews_law_and_identity_politics.pdf

- Chapter 3: Jewish Identity | Pew Research Center, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2013/10/01/chapter-3-jewish-identity/

- About Reform Judaism – Congregation Adas Emuno, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.adasemuno.org/page-18079

- Reform Judaism in 1000 Words: God, accessed on September 22, 2025, https://www.reformjudaism.org.uk/reform-judaism-1000-words-god/

APPENDIX

Understanding Ourselves and Others: A Beginner’s Guide to Jung and Lacan

Introduction: Unlocking New Ways of Seeing

Welcome to the fascinating world of psychoanalytic thought. This guide is designed to introduce four powerful concepts from two of the 20th century’s most influential thinkers, Carl Jung and Jacques Lacan. We will explore Jung’s ideas of the Shadow and Projection, and Lacan’s concepts of the Imaginary and Symbolic orders. Our goal is to make these complex ideas simple, clear, and accessible for anyone new to the topic.

Think of these concepts as tools. They are not just for understanding our own inner worlds, but for gaining a deeper insight into social dynamics, group behavior, and the very construction of identity. By the end of this guide, you will have a new lens through which to see yourself and the world around you. Let’s begin by exploring the toolkit provided by Carl Jung.

1. Carl Jung’s Toolkit: The Shadow and Projection

1.1. What is the ‘Shadow’? Meeting Your Hidden Self

In simple terms, the Jungian shadow is the “dark side” of our personality. It is the part of our unconscious mind that contains all the traits, impulses, and desires that our conscious self—our ego—finds unacceptable and chooses to repress or ignore. This can include feelings like egotism, aggression, greed, and other socially unacceptable desires.

To understand this better, we can contrast our conscious self (the Ego) with our unconscious self (the Shadow).

| The Ego (Our Conscious Self) | The Shadow (Our Unconscious Self) |

| • Our idealized self-image, or persona—the personality we present to the world. | • Contains primitive, negative, and socially unacceptable impulses. |

| • Strives to be seen as good, moral, and socially acceptable. | • Holds the traits we disown, such as greed and aggression. |

| • Represents the conscious “light” side of our personality. | • Represents the “dark side” we refuse to acknowledge in ourselves. |

This concept doesn’t just apply to individuals. Jung also described a collective shadow, which refers to the disowned, darker aspects of an entire society or culture. When a nation or group represses its negative traits, this collective shadow can manifest in destructive historical phenomena like xenophobia, dehumanization, and war.

1.2. What is ‘Projection’? Seeing Our Shadow in Others

Projection is the psychological defense mechanism we use to deal with our shadow. It is the process of taking our own unacknowledged and undesirable qualities and attributing them to someone else or another group. This need to locate inferiority ‘out there’ is crucial, as it prepares a space for a scapegoat—a screen onto which a group can project its darkest traits.

a person “possessed by his shadow is always standing in his own light and falling into his own traps”.

The primary benefit of projection for our ego is that it keeps our idealized self-image intact. By locating evil, corruption, and inferiority outside of ourselves, we can maintain the belief that we are good and virtuous.

The source provides a powerful and chilling real-world example of collective projection. Adolf Hitler systematically designated the Jewish population as a scapegoat, providing the German nation with an out-group onto which it could project its collective shadow. This act of mass projection was then used to justify horrific persecution and violence.

1.3. Section Summary: How Shadow and Projection Work Together

The shadow and projection are deeply connected. When a group refuses to confront its own collective shadow, it almost inevitably projects those negative qualities onto an out-group to maintain a sense of its own goodness. Jung gives us the projectile—the repressed shadow—but Lacan provides the physics of the screen. He explains how the very structure of our identity creates a “target” for such projections.

2. Jacques Lacan’s Toolkit: The Imaginary and the Symbolic

2.1. The ‘Imaginary Order’: The World of Images and the Ego

The Lacanian Imaginary does not mean “make-believe.” Instead, it refers to the fundamental realm of images, identification, and the ego. Its foundational event is the Mirror Stage, a crucial drama in our development.

Here is how the Mirror Stage works:

1. The Fragmented Self: An infant between six and eighteen months experiences a state of “insufficiency,” its body a jumble of uncoordinated sensations and movements—what Lacan calls the “fragmented body.”

2. The Unified Image: The infant then sees its reflection in a mirror. This reflection appears as a “unified, coherent gestalt”—a whole, complete being that anticipates a mastery the infant has not yet achieved.

3. The “Jubilant” Identification: The infant joyfully identifies with this external, unified image. This act of identification with an outside reflection forms the very core of the infant’s ego (which Lacan calls the moi).

The most important insight here is that our ego is fundamentally alienating. It is formed through an act of misrecognition (méconnaissance), by identifying with an image that is outside of ourselves. Our deep-seated feeling of having a unified, coherent self is, in Lacan’s terms, a “necessary fiction” or a “mirage” that masks our actual internal fragmentation.

2.2. The ‘Symbolic Order’: The World of Language and Law

The Symbolic order is the second key realm described by Lacan. It is the world of language, law, social rules, and culture—a “pre-existing network of signifiers” that exists even before we are born. Lacan refers to this as the “big Other,” the trans-individual treasury of signifiers that structures reality.

The critical function of the Symbolic is to move us beyond the purely image-based identity of the Imaginary. When we learn to speak, we become a subject within language (what Lacan calls the je). In the Symbolic, identity is not based on a static, external image, but on one’s position within a structure of language and rules.

2.3. Section Summary: Moving from Image to Language

In short, the Imaginary and the Symbolic represent two different ways of understanding who we are. The Imaginary is about the ego (moi) formed by identification with an external reflection. The Symbolic is about the speaking subject (je) created by finding our position within a shared system of meaning, like language, where we are always shifting within a “chain of signifiers.”

Now, let’s move from theory to practice. We will see how these four concepts are not merely parallel but are deeply interlocking, creating a powerful—and often dangerous—psychic architecture that has shaped centuries of history.

3. An Applied Example: How These Ideas Work in the Real World

This section will use the source’s analysis of antisemitism to demonstrate how these four abstract concepts work together in practice.

3.1. The Trap: How an Image Becomes a Target

By combining Jung and Lacan, we can see how the historically constructed “image of the Jew” functions as a perfect Lacanian imago—a stable, external image. This image then acts as a specular screen for the projection of the non-Jewish collective’s Jungian shadow.

Examples of Projected Shadow Traits:

• Greed and financial manipulation.

• Conspiratorial desire for world domination.

• Theological associations with the devil and deicide.

• Physical stereotypes signifying racial otherness.

But here is the crucial payoff of this psychic strategy: by projecting its collective shadow—greed, materialism, lust for power—onto this stable imago, the non-Jewish collective ego can constitute itself as its virtuous opposite: generous, spiritual, moral, loyal, and rooted. This process isn’t just prejudice; it’s a fundamental strategy for the construction of the non-Jewish self.

3.2. The Defense: Finding Identity in Words, Not Images

The source explains how the Lacanian Symbolic order can function as a powerful defense against the trap of the Imaginary. The primary example given is the system of Halakha, or traditional Jewish Law.

Halakha is a “totalizing Symbolic order”—a comprehensive system that governs every aspect of life, grounding Jewish identity in a relationship to commandments and sacred texts, not in how the outside world sees you. It provides an “internally coherent framework” that acts as a powerful counter to hostile projections.

The psychoanalytic genius of this system lies in its structural opposition to idolatry. The biblical prohibition of graven images is an injunction against the ego’s narcissistic worship of its own reflection. By structuring life around abstract law and text rather than images, Halakha functions as a psycho-spiritual technology for de-centering the ego from the Imaginary’s trap. It is a constant practice of choosing the Symbolic Law over the seductive Imaginary image.

4. Conclusion: A New Lens for Understanding

In this guide, we have explored four key concepts: the Shadow (our disowned self), Projection (seeing our shadow in others), the Imaginary (the realm of images and the ego), and the Symbolic (the realm of language and law).

These concepts reveal a core dialectic in our psychic lives: the perpetual tension between the external images that define us from the outside and the internal systems of meaning we use to define ourselves from within. This is not a historical problem to be solved, but a fundamental and ongoing struggle that shapes who we are. By grasping this tension between the Image and the Word, you gain a critical tool for decoding the complex ways identity is constructed and contested, both within yourself and in the world at large.