Introduction: The Two Kingdoms of the Biblical Landscape

The natural world as depicted in the Tanach is not a passive or neutral backdrop for human and divine drama; rather, it is a divinely authored text, a physical realm imbued with profound symbolic and theological meaning. Within this landscape, every element, from the mightiest cedar to the humblest herb, participates in a sacred economy of life, purity, and holiness. The biblical worldview posits a universe brought into existence by a divine act of will, an act that imposed order upon chaos and separated heavens from earth, animate from inanimate, and light from darkness.1 This created order is understood to be a direct manifestation of God’s power and wisdom, a reality where the regular, life-sustaining cycles of nature—the changing seasons, the falling rain, the growth of plants—serve as a constant testament to the Creator’s benevolent governance.1 As the Psalmist declares, “the heavens are telling the glory of God / and the firmament proclaims his handiwork” (Psalm 19:1).1 Consequently, an analysis of the natural world in the Hebrew Bible must proceed from the understanding that nature is never an end in itself; it consistently points beyond itself to the divine, serving as a primary medium through which God’s character, promises, and judgments are revealed to humanity.1

This paper argues that the Tanach presents a sophisticated and foundational theological dichotomy through its depiction of two distinct biological kingdoms. The first, the kingdom of Flora—encompassing the vast array of trees, grains, fruits, flowers, and herbs—overwhelmingly symbolizes God’s created order, covenantal blessing, sustenance, life, and the very means by which ritual purity (taharah) can be achieved. It is the visible, manifest world of growth and fruitfulness. In stark and deliberate contrast, the second, the Fungal kingdom—represented by the unseen, transformative, and often decaying actions of yeast (chametz), mold (tzaraat), and blight—serves as a powerful cognate symbol. It embodies the pervasive and corrupting forces of sin, ritual impurity (tumah), divine judgment, and death that exist as a consequence of a fractured relationship with the divine within that created world. This is the hidden, insidious world of fermentation and decay. The profound theological symbolism assigned to these two kingdoms is not arbitrary; it is deeply rooted in their fundamental and observable biological roles. Plants, as primary producers that create sustenance from earth, water, and sun, naturally mirror the divine act of creating life and order. Conversely, fungi, as decomposers that break down existing organic matter, provide a powerful natural analogue for the theological concepts of decay, corruption, and the mortal return to dust.

This study will proceed by first conducting an exhaustive examination of the multifaceted and overwhelmingly positive roles of flora within the agricultural, economic, ritual, and symbolic life of ancient Israel. It will then perform a detailed analysis of the consistently negative theological function assigned to fungal phenomena. Finally, it will synthesize these findings to illuminate a core tension in biblical theology: the reality of navigating a world that is at once God’s good creation and yet is profoundly marked by forces of corruption and decay. The analysis will rely upon scholarly efforts to identify the plants and phenomena described in the biblical text, while fully acknowledging the inherent complexities, debates, and occasional uncertainties that characterize this field of study.3 Through this comparative lens, the intricate relationship between the verdant and the unseen emerges not as a simple list of natural elements, but as a dynamic symbolic system that undergirds the biblical understanding of life, death, holiness, and sin.

The Cultivated Earth: Flora as Divine Blessing and Sustenance

The flora of the Tanach serves as the very foundation of physical and spiritual life in ancient Israel. From the staple grains that sustained the populace to the mighty trees that built the Temple and the fragrant herbs used in sacred rituals, plants are the tangible medium of God’s provision and the primary symbol of covenantal blessing. The cultivated field, rather than the untamed wilderness, stands as the biblical model for the created universe, a realm where human stewardship, enacted through agriculture, partners with divine benevolence to bring forth life and order.1 An exploration of the Tanach’s flora reveals a highly structured symbolic world where different categories of plants correspond to distinct spheres of religious and social life, all reinforcing the central theme that a right relationship with God results in the flourishing of the land.

The Seven Species (Shiv’at HaMinim): Archetypes of a Promised Land

At the apex of the biblical botanical hierarchy stand the Seven Species, the seven agricultural products listed in Deuteronomy 8:8 as the defining features of the Promised Land’s fertility: “a land of wheat and barley, of vines and fig trees and pomegranates, a land of olive oil and honey”.6 These seven products—two grains and five fruits—are not merely a list of foodstuffs but are the archetypal symbols of the covenant fulfilled, representing the transition from a nomadic existence in the wilderness to a settled, agrarian life in a land blessed by God.7 Their presence and prosperity were the physical evidence of divine favor.

The economic and agricultural importance of the Seven Species was paramount. Wheat (Triticum vulgare) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) were the two foundational grains of the ancient Israelite diet, providing the flour for bread, the staple of daily life.6 The other five species—the grapevine (Vitis vinifera), fig tree (Ficus carica), pomegranate tree (Punica granatum), olive tree (Olea europaea), and date palm (Phoenix dactylifera)—provided essential fruits that were easy to store, process, and trade, ensuring sustenance throughout the year.7 Grapes were pressed into wine, a cornerstone of celebrations; olives yielded oil, used for food, light, and anointing; figs were pressed into cakes for preservation; and dates were boiled into a thick syrup, the “honey” (d’vash) that gave the Promised Land its epithet.7 Together, they formed the backbone of the Israelite economy, with Solomon recorded as trading vast quantities of wheat, barley, and oil with Hiram of Tyre.8

This agricultural cycle was inextricably woven into Israel’s ritual and liturgical calendar, sanctifying the process of cultivation and harvest. The agricultural year began with the barley harvest, marked by the Omer offering brought to the Temple during Passover.6 The subsequent wheat harvest culminated in the festival of Shavuot (Pentecost), also known as the Feast of Weeks, celebrated with an offering of two leavened loaves made from the new wheat.9 The fall harvest of grapes, figs, pomegranates, and dates was celebrated during Sukkot, the Feast of Tabernacles.6 The sacred status of these seven products was codified in the Mishnah, which states that the offering of first fruits (bikkurim) brought to the Temple in a ceremony of great rejoicing could only be from the Seven Species.9 This legal distinction elevated them from mere crops to ritual objects, direct links between the fertility of the land and the worship of its divine benefactor.

Beyond their economic and ritual roles, each of the Seven Species accrued a deep layer of spiritual symbolism, with later Jewish mystical traditions associating them with the divine attributes (sefirot).12

- Wheat (Chitah חיטה): As the primary ingredient for bread, wheat became a symbol of life itself and God’s fundamental provision.11 It is associated with the divine attribute of kindness (chesed), representing the abundant goodness that sustains creation.10

- Barley (Se’orah שעורה): A hardier and humbler grain, often the food of the poor and of animals, barley represents strength, hard work, and the divine attribute of restraint or judgment (gevura).6 Its characteristic hull, which remains even after threshing, was seen as a physical manifestation of setting boundaries.12

- Grapes (Gefen גפן): The source of wine, grapes are a universal symbol of joy, celebration, and prosperity.11 They are linked to the attribute of harmony (tiferet), the balance between kindness and restraint.12 The grapevine also served as a potent metaphor for the nation of Israel itself, whose spiritual fruitfulness was a measure of its faithfulness to God.10

- Figs (Te’enah תאנה): The fig tree, with its broad leaves providing deep shade, became the ultimate symbol of peace, security, and prosperity. The idyllic image of a golden age is captured in the phrase, “every man under his own vine and fig tree” (1 Kings 4:25).6 Later tradition saw in the fig’s unique ripening pattern—where fruit appears sequentially over a long season—a metaphor for the patient, daily acquisition of wisdom from one’s teachers.12 It is associated with the attribute of eternity or endurance (netzach).10

- Pomegranates (Rimon רימון): This majestic fruit, with its crown-like calyx and multitude of seeds, symbolizes righteousness, fruitfulness, and divine glory (hod).6 Its likeness was woven into the hem of the High Priest’s robe and carved into the pillars of Solomon’s Temple, marking it as a fruit of sacred importance.9 A well-known tradition teaches that the pomegranate contains 613 seeds, corresponding to the 613 commandments of the Torah.6

- Olives (Zayit זית): The olive tree is one of the most enduring biblical symbols, representing peace, longevity, and divine light. Its oil, a product of intense pressing, fueled the eternal flame of the Menorah in the sanctuary and was used to anoint priests and kings, consecrating them for divine service.6 The olive is thus linked to the attribute of foundation (yesod), the channel through which divine blessing flows into the world.10

- Dates (Tamar תמר / D’vash דבש): The tall, straight growth of the date palm made it a symbol of the righteous person (tzaddik), who flourishes and stands upright (Psalm 92:12).11 The “honey” produced from its fruit represents the sweetness of the Promised Land and is associated with the attribute of royalty or sovereignty (malchut).10

The significance of these plants is thus profoundly tied to a theology of place. Their value derives not only from their inherent qualities but from the fact that they are the specific produce of the Land of Israel.9 The promise articulated in Deuteronomy is not of generic sustenance, but of “a land of wheat and barley…”.6 The flora thereby defines the very identity and sanctity of the land. The flourishing of these particular species serves as the tangible evidence of God’s fidelity to the covenant, while their failure, whether through drought or blight, is a direct sign of covenantal breach. The Seven Species are therefore not merely symbols; they are the physical embodiment of the covenantal relationship, linking the people’s moral and spiritual state directly to the productivity of the specific, sacred geography they inhabit.

Trees of Life, Wisdom, and Righteousness

Beyond the foundational Seven Species, the Tanach accords special significance to a number of prominent trees, which often function as markers of sacred space, sites of divine encounters, and powerful metaphors for moral character and national destiny. These towering and long-lived members of the plant kingdom stand as silent witnesses to the unfolding history of Israel, their physical attributes providing a rich vocabulary for theological expression.

The Cedar of Lebanon (Erez, ארז; Cedrus libani) is the quintessential biblical symbol of strength, majesty, grandeur, and permanence.14 Renowned throughout the ancient world, its durable and fragrant wood was the material of choice for the most sacred and royal constructions. God instructed that it be used for Solomon’s Temple, the earthly dwelling place for the divine presence, and for the king’s palace, signifying its supreme status.14 However, its very loftiness also made it a potent symbol for human pride and arrogance. The prophets frequently used the image of the mighty cedar being brought low as a metaphor for God’s judgment against the proud, whether they be foreign kings or the nation of Israel itself (Isaiah 2:13; Ezekiel 31:3).15

The sturdy and resilient Oak (Alon, אלון; Quercus calliprinos) and Terebinth (Elah, אלה; Pistacia palaestina) are frequently mentioned as landmarks in the patriarchal narratives and as sites of divine revelation.16 Abram’s first encounter with the land is at the “oak of Moreh” (Genesis 12:6), Jacob buries idols under a terebinth (Genesis 35:4), and an angel sits under a terebinth when visiting Gideon (Judges 6:11).16 The Hebrew names for both trees, alon and elah, contain the root ‘el (אל), a name for God, reflecting a pre-Israelite association of these trees with divinity.16 This sacred status made them natural places for worship, but also sites for idolatrous practices condemned by the prophets, such as Hosea’s denunciation of those who “burn offerings on the hills… under oak, poplar and terebinth trees” (Hosea 4:13).16 Critically, the remarkable ability of these trees to regenerate and sprout new shoots even after being cut down provided a powerful botanical metaphor for Israel’s hope of survival and restoration. Isaiah’s prophecy that “as the terebinth and oak leave stumps when they are cut down, so the holy seed will be the stump in the land” (Isaiah 6:13) draws directly on this natural phenomenon to promise a future remnant.16

In contrast to the majestic cedar, the humble Acacia (Shittah, שטה; Acacia raddiana or Acacia tortilis) is a hardy tree of the wilderness. Its significance lies not in its grandeur but in its divinely mandated role in the construction of the Tabernacle. The wood of the acacia was specified for building the most sacred objects of Israel’s desert sanctuary: the Ark of the Covenant, the poles to carry it, the table for the showbread, and the altar of burnt offering (Exodus 25:10, 23; 27:1).15 The choice of this resilient desert wood symbolizes the presence of enduring holiness and divine order even in the midst of a desolate and transient environment.

These specific trees contribute to a broader biblical motif: the righteous person as a flourishing tree. This powerful metaphor, central to wisdom literature, connects moral integrity with the life-giving order of the natural world. The Psalmist declares that the righteous individual “is like a tree planted by streams of water that yields its fruit in its season, and its leaf does not wither” (Psalm 1:3).18 Similarly, Psalm 92:12 proclaims, “The righteous will flourish like a palm tree… planted in the house of the LORD”.18 This imagery suggests that a life lived in accordance with divine law is a life aligned with the very principles of growth and stability that govern the natural world. The ultimate expression of this idea is the designation of the Torah itself as Etz Chaim, a “Tree of Life,” the ultimate source of spiritual sustenance and wisdom.18

This symbolic use of flora reveals a clear hierarchy of botanical significance that mirrors the theological and social structure of ancient Israel. At the highest level are the Seven Species, directly linked to the national covenant, the Promised Land, and the central Temple festivals. Below them are the great trees like the Cedar, Oak, and Terebinth, which are associated with the monarchy, foundational patriarchal narratives, and major prophetic pronouncements. Finally, as will be discussed, there are the common herbs and flowers integrated into the daily purification rituals and economic obligations of the populace. This mapping of plants to distinct spheres of religious life—national/Temple, prophetic/patriarchal, and individual/household—is not coincidental. It reflects a worldview in which the divinely created natural order serves as a mirror and a reinforcing structure for the divinely ordained social and spiritual order. The very structure of the plant world provides a tangible language for understanding the structure of the holy community.

The Fragrance of the Sacred: Herbs, Spices, and Flowers

While trees and staple crops formed the visible architecture of the biblical landscape, a host of smaller plants—herbs, spices, and flowers—played crucial and intimate roles in the daily and ritual life of ancient Israel. These plants, often characterized by their fragrance or specific properties, were essential for purification ceremonies, worship, medicine, and cuisine. Their integration into the sacred economy demonstrates that even the humblest flora were seen as divinely provided tools for maintaining holiness and navigating the relationship between God and humanity.

Certain plants were designated as primary agents of ritual purification, their use mandated in the Torah for cleansing individuals and spaces from impurity. The most prominent of these is Hyssop (Ezov, אזוב), which modern scholars identify not with common hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis) but with Syrian oregano (Origanum syriacum), a member of the mint family known locally as za’atar.20 Hyssop’s role was central to Israel’s most formative and significant rituals. It was the instrument used to daub the blood of the Passover lamb on the doorposts in Egypt, protecting the Israelites from the final plague (Exodus 12:22).20 It was also a key component in the complex purification rites for those who had contracted tzaraat or had come into contact with a corpse, where it was used to sprinkle purifying waters (Leviticus 14:4-6).21 This consistent ritual use imbued hyssop with a powerful symbolic meaning, making it the archetypal symbol of spiritual cleansing, as famously invoked by David in his plea for forgiveness: “Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean” (Psalm 51:7).21

The air of the Tabernacle and Temple was filled with the scent of sacred incense, a carefully prescribed blend of precious aromatic resins. Chief among these were Frankincense (Levonah, לבונה) and Myrrh (Mor, מור). Frankincense is a resin derived from trees of the Boswellia genus, while myrrh comes from Commiphora species.17 Both were highly valued commodities, often imported, and were key ingredients in the holy incense burned on the golden altar and in the sacred anointing oil used to consecrate priests and sacred vessels (Exodus 30:34).20 Their fragrant smoke symbolized the prayers of the people ascending to God, and their presence signified a space or person set apart as holy. Myrrh was also used as a perfume and for medicinal purposes.17

Beyond the central sanctuary, a variety of herbs and spices were integrated into the daily religious and economic life of the people. The practice of tithing even common garden herbs like mint (Mentha longifolia), dill (Anethum graveolens), and cumin (Cuminum cyminum) indicates their recognized value and place within the agricultural system that supported the priesthood.20 The Torah uses the seed of the coriander plant (Coriandrum sativum) to describe the appearance of the miraculous manna provided in the wilderness (Exodus 16:31), linking this common spice to divine provision.17 The Israelites’ nostalgic longing for the garlic (Allium sativum), leeks (Allium porrum), and onions (Allium cepa) they ate in Egypt highlights the importance of these pungent bulbs as essential components of their diet (Numbers 11:5).17

While precise botanical identifications are often debated, flowers appear in the Tanach as collective symbols of beauty, God’s providential care, and the fragility of human life.25 The adornment of the Temple menorah and pillars with “lily flowers” (shoshan) suggests that floral motifs were an integral part of sacred art and architecture.25 The “lily of the valley” (shoshannat ha’amakim) is likely the narcissus, while the “rose/lily of Sharon” (ḥavatzelet ha-Sharon) may refer to the sea daffodil or the tulip.25 Perhaps the most famous floral image is the “lilies of the field,” which Jesus used to teach about trusting in God’s provision (Matthew 6:28-30). Scholars suggest this likely refers to the brilliant red Crown Anemone (Anemone coronaria), which carpets the hills of the Galilee in springtime, a spectacular and visible display of natural splendor that outshines even the royal robes of Solomon.24 The prophetic vision of the desert bursting into bloom “like the crocus” (Isaiah 35:1) uses the image of a flower to symbolize the hope of messianic restoration and the renewal of all creation.25

The Unseen Kingdom: Fungi as a Theological Counterpart

In direct theological opposition to the life-giving, orderly, and visible kingdom of flora, the Tanach presents a cognate world of fungal phenomena. This unseen kingdom, characterized by processes of fermentation, decay, and contagion, functions as a powerful and consistent metaphor for the hidden, pervasive, and corrupting influences that threaten the sacred order of creation. Where plants symbolize divine blessing and the means to achieve purity (taharah), the manifestations of fungi—leaven, mold, and blight—are the quintessential symbols of sin, ritual impurity (tumah), and divine judgment. Their study reveals a sophisticated theological framework for understanding the nature of corruption in a world created good.

Leaven (Chametz): The Metaphor of Pervasive Internal Influence

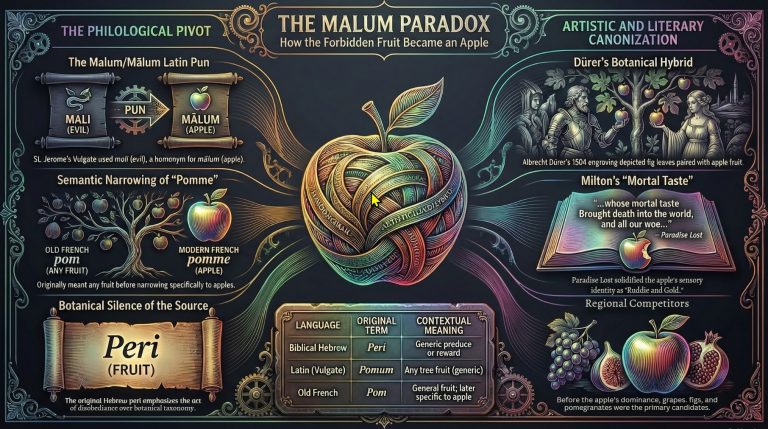

The most developed fungal metaphor in the Tanach is that of leaven, the fermenting agent—yeast—used to make bread rise. The Hebrew term for a leavening agent is se’or (שְׂאוֹר), while the final leavened product is known as chametz (חָמֵץ).29 The symbolism of chametz is primarily articulated through its strict prohibition during the seven-day festival of Passover, or the Feast of Unleavened Bread. The Torah commands the Israelites to remove all se’or and chametz from their homes and to refrain from consuming any leavened products for the duration of the festival (Exodus 12:15-20).31

On a historical level, this practice serves as a physical commemoration of the Exodus from Egypt. The Israelites fled in such haste that they had no time to wait for their dough to rise, baking unleavened cakes (matzot) for their journey (Exodus 12:39).33 The “bread of affliction” (Deuteronomy 16:3) thus becomes an annual reminder of the speed and urgency of their liberation.

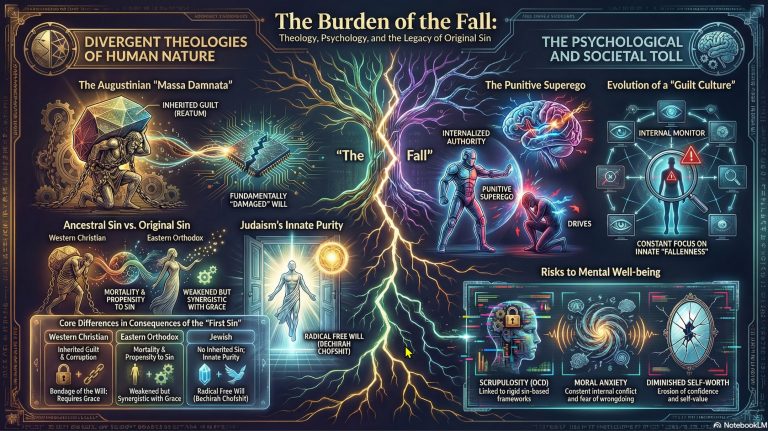

However, the symbolism of chametz extends far beyond this historical commemoration into the realm of the spiritual and ethical. This deeper meaning is signaled by another crucial law in the Torah: the absolute prohibition of leaven (and honey, another agent of fermentation) from any grain offering (minchah) burned on the altar (Leviticus 2:11).30 This law establishes leaven as a substance of corruption, an element unfit for the divine presence. The very etymology of chametz is linked to the Hebrew word for “sour” (chamutz), reflecting the process of fermentation that sours and alters the pure grain.31 This physical process becomes a potent metaphor for a spiritual one. Rabbinic tradition explicitly identifies the “yeast in the dough” as a symbol for the yetzer ha’ra, the evil inclination within the human heart that corrupts, ferments, and sours the soul.29

The defining biological characteristic of yeast—its ability for a minuscule amount to permeate and transform an entire batch of dough—is the key to its symbolic power.33 “A little leaven leavens the whole lump” (Galatians 5:9, reflecting a common proverb).29 This makes it the perfect metaphor for the insidious and pervasive nature of sin, particularly the sin of pride. A small, hidden seed of arrogance or transgression, if left unchecked, can puff up and corrupt a person’s entire character, just as a small amount of yeast puffs up a loaf of bread.30 The annual ritual of bedikat chametz (the search for leaven) and bi’ur chametz (the destruction of leaven) thus transforms from a simple act of “spring cleaning” into a profound spiritual discipline. The meticulous, candlelit search for any last crumb of leavened bread becomes a symbolic act of introspection, a searching of the soul’s hidden corners to identify and purge the corrupting influence of pride and sin before entering the sacred time of the festival.30 While a minority of texts, particularly in the New Testament, use the pervasive quality of leaven in a positive sense to describe the growth of God’s kingdom (Matthew 13:33), its dominant role within the ritual framework of the Tanach is overwhelmingly negative, representing a corrupting force that must be diligently expunged to maintain a state of purity.29

Mould, Mildew, and Blight: The Contagious External Corruption

While chametz represents an internal, insidious corruption, the Tanach also describes external afflictions of decay on crops, fabrics, and homes. These phenomena, which modern scholarship identifies as fungal in nature, function as tangible, visible manifestations of impurity and divine judgment that threaten the community from without.

The most detailed description of such an affliction is tzaraat (צָרַעַת), a term found extensively in Leviticus 13-14. While historically mistranslated as “leprosy,” this identification is now widely considered erroneous, as the biblical descriptions do not align with the symptoms of Hansen’s disease.39 Crucially, tzaraat could affect not only human skin but also woolen or linen garments and the stone walls of houses. In these inanimate objects, the affliction is described as appearing in “greenish or reddish streaks” that seem to be “below the surface of the wall” (Leviticus 14:37).42 This description strongly suggests a form of mold or mildew.39 Scholars have noted the similarity to toxic black mold (Stachybotrys), which thrives in damp conditions and can cause serious health issues, lending scientific plausibility to the biblical account of an affliction affecting both humans and their dwellings.39

Theologically, the most significant aspect of tzaraat is that it is treated as a matter of ritual impurity (tumah), not simply as a structural or hygienic problem. The diagnosis and remediation are handled exclusively by a priest (kohen), not a physician or builder.42 The presence of this “persistent defiling mold” (Leviticus 14:44) renders a house ritually impure (tamei), making it unfit for habitation within the holy community where God dwells.43 The prescribed ritual is a careful, escalating process: an initial inspection by the priest, a seven-day quarantine, the removal and disposal of infected stones, the scraping of the interior walls, and, if the mold reappears, the complete demolition of the house.43 This elaborate procedure underscores the gravity of the affliction; it is a deep-seated corruption, a physical manifestation of a spiritual contagion that must be radically purged to protect the sanctity of the community.44 Rabbinic tradition later interpreted tzaraat as a supernatural punishment for sins like gossip and arrogance, a divine warning made visible on one’s body or home.40

In the agricultural sphere, the fungal phenomena of blight and mildew serve a similar theological function. In the covenantal blessings and curses outlined in Deuteronomy, “blight and mildew” are listed as divine punishments for disobedience, set in direct opposition to the agricultural abundance promised for faithfulness (Deuteronomy 28:22).46 The prophets Haggai and Amos later invoke these crop-destroying fungi as instruments of divine judgment, chastising the people of Israel for their spiritual apathy. God declares through Haggai, “I struck you—all the work of your hands—with blight, mildew, and hail, yet you did not turn to Me” (Haggai 2:17).46 Here, the fungus is not a random natural disaster but a targeted message, a destructive force sent by God to call a spiritually stubborn people back to a right relationship with Him.48 In this context, blight and mildew are the fungal antithesis of the flourishing Seven Species; they are the sign of a broken covenant made manifest in the decay of the very crops that were meant to be a sign of blessing.

The biblical treatment of these different fungal phenomena reveals a nuanced understanding of contagion and corruption. Chametz functions as a model for an internal, voluntary corruption; one allows the “leaven” of pride or sin to enter the self, where it secretly permeates one’s character. Its removal is a matter of personal, introspective responsibility. Tzaraat, by contrast, serves as a model for an external, involuntary affliction that renders one ritually impure and requires the intervention of an outside authority—the priest—for its resolution. It is a contagious state that affects one’s standing within the community. This distinction mirrors different theological dimensions of sin: the internal state of the heart that requires repentance and self-examination, and the external consequences of sin that can pollute the community and require formal, mediated rites of atonement. The different manifestations of the fungal kingdom are thus used not as redundant symbols of “badness,” but to articulate a sophisticated theology of sin, impurity, and the multifaceted means of purification.

The Silent Kingdom: The Anomaly of Mushrooms

A striking feature of the Tanach’s extensive engagement with the natural world is the conspicuous absence of mushrooms. In a collection of texts so deeply rooted in the land, which meticulously catalogues hundreds of plant species from towering cedars to humble hyssop, this silence is significant.17 The complete lack of mention of mushrooms in the primary narratives, legal codes, and poetic literature of the Hebrew Bible places them in a unique and anomalous category, setting them apart from the ordered world of flora.

This anomalous status is addressed and clarified in later rabbinic thought, particularly in the Talmud. When discussing the proper blessing to be recited before eating various foods, the sages grappled with how to classify mushrooms.50 They observed that mushrooms, unlike plants, do not appear to draw their sustenance from the soil; they can grow on decaying wood or other organic matter and lack the visible seeds, roots, and photosynthetic processes of flora.50 Consequently, they concluded that the standard blessing for agricultural produce, “borei pri ha’adamah” (“who creates the fruit of the earth”), was inappropriate. Instead, mushrooms were assigned the generic, all-encompassing blessing, “she’hakol ni’hi’ye bidvaro” (“by whose word all things come to be”), the same blessing recited over water, meat, or fish.51 This legal ruling effectively places mushrooms outside the entire symbolic system of agriculture that is so central to biblical theology.

This unique biological and halakhic (legal) status provides a powerful key to understanding their symbolic position—or lack thereof. In a worldview that prizes the cultivated field as the primary model of divine order and human partnership with God 1, mushrooms represent a form of life that is fundamentally “other.” They are uncultivated, appearing unpredictably in dark, damp places, often on matter that is dead or decaying. They do not fit into the established, life-giving categories of creation. Later Jewish mystical thought (Kabbalah) seized upon this otherness, drawing a symbolic connection between the Hebrew word for mushroom, pitriah (פטריה), and the word for “exempt” or “irresponsible,” patur (פטור).52 In this interpretation, the mushroom, with no visible roots anchoring it to the soil, becomes a metaphor for an uncommitted, irresponsible entity that avoids the demands and attachments of community life.52 This reinforces the position of mushrooms as outsiders to the symbolic system of ordered, rooted, life-giving flora that represents righteousness and covenantal faithfulness. Their silence in the Tanach is not an oversight but a reflection of their perceived status as an anomaly in God’s ordered creation.

A unifying theme for the entire fungal kingdom’s symbolism is the concept of “hiddenness.” The action of yeast is microscopic and internal to the dough, an invisible agent of transformation.30 Mold, as tzaraat in a house, is described as appearing from deep within the walls, its source unseen.43 Agricultural blight can destroy a crop from within, its mycelial network spreading invisibly before the symptoms become manifest. This characteristic of hiddenness stands in sharp contrast to the visible, manifest nature of flora: the tall cedar, the vast fields of grain, the fruit hanging on the branch. This opposition between the visible and manifest (flora) and the hidden and insidious (fungi) provides a powerful structural element to the biblical theology of nature. It offers a tangible language to articulate the crucial difference between outward righteousness, symbolized by a healthy, flourishing tree, and inward corruption, symbolized by the hidden leaven of the heart.

Synthesis and Conclusion: A World of Order and Its Inherent Decay

The comprehensive analysis of flora and its fungal cognate in the Tanach reveals a deeply integrated symbolic system that articulates a central theological tension of the biblical worldview: the reality of a world created good by God, yet subject to the pervasive forces of corruption, decay, and death. The plant and fungal kingdoms are not merely illustrative but serve as the primary physical language through which the abstract concepts of purity and impurity, blessing and curse, life and death are understood and ritually navigated. By synthesizing the opposing roles of these two kingdoms, we can crystallize the ancient Israelite understanding of their place within a sacred yet fallen creation.

Purity (Taharah) vs. Impurity (Tumah): A Botanical and Mycological Axis

The biblical system of ritual purity and impurity—taharah and tumah—provides the clearest lens through which to view the theological dichotomy between flora and fungi. This system is not primarily concerned with hygiene or morality in the modern sense, but with ritual fitness for approaching the sacred presence of God.53 Holiness, the essential attribute of God, is a source of intense life, and impurity, often linked to death and decay, is its antithesis and cannot exist in its presence.55

Flora is consistently aligned with the state of purity and is even an active agent in its restoration. The ideal state of the land and its people is represented by flourishing fields and fruitful trees, symbols of a pure, ordered existence.19 More than just symbols, specific plants are essential components in the Torah’s purification rituals. Cedarwood, known for its resistance to rot, and hyssop, the herb of cleansing, are mandated ingredients in the ceremony to purify a person or a house from the severe impurity of tzaraat and from contact with a corpse (Leviticus 14:4-7).21 This demonstrates a core theological principle: the ordered, living world of plants provides the very means to counteract the forces of impurity, decay, and death. Flora is thus an instrument of taharah.

Conversely, fungal phenomena are primary sources and symbols of ritual impurity. The presence of chametz in a home during Passover creates an impure space, and it must be violently purged to restore the home to a state of ritual fitness for the festival.30 The fungal affliction of tzaraat on a person or a house is a source of severe tumah, a contagion so potent that it requires quarantine and exile from the holy community until it can be ritually cleansed.42 This establishes a clear and consistent axis within the biblical purity system: flora is aligned with taharah and proximity to the holy, while fungi are aligned with tumah and the resulting separation from the holy.

| Theological Concept | Role of Flora (The Verdant Kingdom) | Role of Fungi (The Unseen Kingdom) |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship to Creation | Represents Primary Creation, Divine Order, and Life | Represents Post-Fall Decay, Disorder, and Death |

| Source of… | Sustenance, Nourishment, Healing | Corruption, Spoilage, Disease |

| Ritual Status | Agent of Purity (Taharah) and Sanctification | Source of Impurity (Tumah) and Contagion |

| Divine Interaction | Symbol of Covenantal Blessing and Reward | Symbol of Covenantal Curse and Judgment |

| Human Response | Cultivation, Stewardship, Thankful Offering | Purging, Avoidance, Ritual Cleansing |

Creation’s Order and the Consequence of Decay

This symbolic axis of purity and impurity can be framed within the grand biblical narrative of creation and its subsequent fracture. The world of flora, in its ideal state, serves as an image of the primordial, life-sustaining order of the Garden of Eden. The biblical emphasis on the cultivated garden and field as the model for creation reflects a theology that values order, productivity, and human partnership with God in tending the earth.1 The promise of the Seven Species flourishing in the Land of Israel is, in essence, a promise of a restored taste of this Edenic blessing, a tangible sign of God’s life-giving presence with His people. The righteous person, like a tree planted by water, partakes in this ideal, life-sustaining order.18

In stark contrast, the negative manifestations of the fungal kingdom—fermentation, mold, blight—represent the physical reality of a post-Edenic world. They are the tangible evidence of the forces of death and decay that entered creation as a consequence of humanity’s alienation from God. This interpretation is supported by theological frameworks that view pathogenic fungi and other destructive natural forces as a result of the Fall and the subsequent curse on the ground (Genesis 3:17-18).57 The ever-present threat of leavening, the potential for mold to appear in one’s home, and the vulnerability of crops to blight are constant reminders that humanity lives “outside of Eden”.55 They are the signs of a world where corruption is an active force that must be perpetually contended with, ritually managed, and diligently purged.

The coexistence of these two symbolic kingdoms in the biblical text and in the lived reality of ancient Israel encapsulates a core theological tension. The world is unequivocally God’s good creation, filled with His life-giving blessings, made manifest in the beauty and bounty of its flora. Yet, it is simultaneously a world profoundly affected by sin, decay, and death, forces made manifest in the insidious and corrupting action of fungi. The intricate laws and powerful symbols surrounding plants and fungi provided the ancient Israelites with a tangible, ritualized framework for navigating this tension. Their religious life was, in many ways, a constant process of choosing life over death, purity over corruption, the flourishing tree over the hidden leaven.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of a Symbolic World

The flora of the Tanach, in conjunction with its fungal cognate, forms a sophisticated and coherent symbolic system that is central to the biblical theological worldview. This paper has demonstrated that plants overwhelmingly represent divine blessing, life, order, and purity, while fungal phenomena consistently symbolize curse, death, decay, and impurity. This dichotomy is not an arbitrary literary device but is grounded in the observable biological roles of these organisms as producers and decomposers, respectively. From the Seven Species that define the sanctity of the Promised Land, to the hyssop that purifies from death, flora is the medium of God’s benevolent and life-sustaining presence. Conversely, from the chametz that corrupts from within, to the tzaraat that pollutes from without, fungi give tangible form to the spiritual forces that threaten this sacred order.

It is crucial to acknowledge the scholarly challenges inherent in this field of study. The precise botanical identification of every plant mentioned in the Bible remains a subject of ongoing research and debate, complicated by the passage of millennia, changes in language, and the generic nature of many biblical terms.3 However, the immense theological and symbolic power of this natural framework transcends the need for exact speciation in every case. Whether the “lily of the field” is an anemone or a tulip, its function as a symbol of God’s magnificent provision remains intact. Whether the tzaraat on the walls was Stachybotrys or another mold, its role as a signifier of ritual contagion is undiminished.

Ultimately, by studying the verdant and the unseen kingdoms as presented in the Tanach, we gain a profound insight into the mind of ancient Israel. It was a mind that did not see a secular, neutral environment, but a world saturated with meaning. It saw in the fields, forests, vineyards, and even in the decay on its walls, a dynamic and ongoing story of divine creation, covenantal responsibility, and the enduring struggle between the forces of life and death. This ancient way of reading the book of nature remains a powerful legacy, inviting a deeper appreciation for the intricate ways in which the physical world can both shape and articulate the spiritual imagination.

Works cited

- Nature in the Sources of Judaism | American Academy of Arts and Sciences, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.amacad.org/publication/daedalus/nature-sources-judaism

- Judaism and The Rhythms of Nature | jewishideas.org – Institute for Jewish Ideas and Ideals, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.jewishideas.org/article/judaism-and-rhythms-nature

- Medicinal plants of the Bible—revisited – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6882220/

- Diuretic plants in the Bible: ethnobotanical aspects – PubMed, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26913893/

- PLANTS of the BIBLE – Michael Zohary – The Zev Vilnay Chair for the Study of the Knowledge of Land of Israel and its Archaeology, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://vilnay.kinneret.ac.il/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Plants-of-the-Bible-.pdf

- The Seven Species of Israel in the Bible and Today — FIRM Israel, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://firmisrael.org/learn/the-seven-species-of-israel-in-the-bible-and-today/

- The Seven Plant Species – A Basis of Nutrition of Ancient Israel, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://biomedres.us/fulltexts/BJSTR.MS.ID.004239.php

- AGRICULTURE – JewishEncyclopedia.com, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/910-agriculture

- Seven Species – Wikipedia, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seven_Species

- What Are the Seven Species of Israel? – IFCJ Learning Center, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.ifcj.org/learn/resource-library/what-are-the-seven-species-of-israel

- The Seven Species of Israel – ONE FOR ISRAEL Ministry, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.oneforisrael.org/bible-based-teaching-from-israel/the-seven-species-of-israel/

- The Seven Species – My Jewish Learning, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-seven-species/

- Revealing the Hebrew Meanings of the Seven Species of the Land of Israel – hebrewversity, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.hebrewversity.com/revealing-hebrew-meanings-seven-species-land-israel/

- Biblical Plants – Missouri Botanical Garden, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/gardens-gardening/our-garden/notable-plant-collections/biblical-plants

- The Symbolic Meanings of 7 Trees in the Bible | by Steppes of Faith – Medium, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://steppesoffaith-56895.medium.com/the-symbolic-meanings-of-7-trees-in-the-bible-64adcd4b2e5

- Under the Oak and Terebinth Trees – Israel Institute of Biblical Studies, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://israelbiblicalstudies.com/blog/category/holy-land-studies/two-biblical-trees/

- Plants of the Bible and Middle East | Walter Reeves: The Georgia Gardener, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.walterreeves.com/landscaping/plants-of-the-bible-and-middle-east/

- The Torah of Trees… – Hebrew for Christians, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.hebrew4christians.com/Holidays/Winter_Holidays/Tu_B_shevat/Torah_Trees/torah_trees.html

- Flora and Fauna – Topical Bible, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://biblehub.com/topical/f/flora_and_fauna.htm

- Plants of the Bible – Natures Way Resources, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.natureswayresources.com/plants-of-the-bible/

- 5 biblical plants with medicinal properties – CUW’s blog – Concordia University Wisconsin, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://blog.cuw.edu/5-biblical-plants-with-medicinal-properties/

- Biblical Herbs in Modern Life: Ancient Roots, Living Remedies – Lev Haolam, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://tl.levhaolam.com/blog/tpost/y5kjdn42x1-biblical-herbs-in-modern-life-ancient-ro

- Bible Herbs, accessed on October 22, 2025, http://www.herbsociety-stu.org/bible-herbs.html

- Plants Of The Garden – The Bible Garden – Charles Sturt University, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.csu.edu.au/special/accc/biblegarden/plants-of-the-garden

- Flowers in Judaism – Wikipedia, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flowers_in_Judaism

- Plants and flowers of the Bible in Israel, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.flowers-israel.net/page/plants-and-flowers-of-the-bible-in-israel

- List of plants in the Bible – Wikipedia, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_plants_in_the_Bible

- The Beautiful Land: Biblical Flora of the Holy Land | Bridges for Peace, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.bridgesforpeace.com/article/beautiful-land-biblical-flora-holy-land

- Lessons from Leaven – Jews for Jesus, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://jewsforjesus.org/blog/lessons-from-leaven

- The Removal of Chametz – Hebrew for Christians, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://hebrew4christians.com/Holidays/Spring_Holidays/Pesach/Chametz/chametz.html

- Chametz – Wikipedia, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chametz

- Hametz: Leaven Forbidden on Passover | My Jewish Learning, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/leaven-hametz/

- What does leaven symbolize in the Bible? | GotQuestions.org, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.gotquestions.org/leaven-in-the-Bible.html

- Yeast or Leavened? PDF FINAL – Torah Family, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://torahfamily.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Yeast-or-Leavened-PDF-FINAL.pdf

- Leaven and Passover | Beth Immanuel Messianic Synagogue, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.bethimmanuel.org/articles/leaven-and-passover

- What is the significance of leaven/yeast in the Bible? – JesusAlive.cc, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://jesusalive.cc/significance-leaven-yeast-in-bible/

- Yeast In the Soul – Passion For Truth Ministries, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://passionfortruth.com/world-holidays/yeast-in-the-soul/

- Topical Bible: Yeast, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://biblehub.com/topical/y/yeast.htm

- Mold: “tsara’at,” Leviticus, and the history of a confusion – PubMed, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14593226/

- Tzaraat–A Biblical Affliction | My Jewish Learning, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/tzaraat-a-biblical-affliction/

- Mold: ” Tsara’at, ” Leviticus, and the History of a Confusion, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://ir.vanderbilt.edu/bitstream/handle/1803/7482/Sasson-Mold.pdf

- Tzaraath – Wikipedia, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tzaraath

- Why does the Old Testament Law say so much about mildew? | GotQuestions.org, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.gotquestions.org/mildew-in-the-Bible.html

- A Disease that Walls Get? Decoding Tzaraat and Facing Our Fears – Reform Judaism, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://reformjudaism.org/learning/torah-study/torah-commentary/disease-walls-get-decoding-tzaraat-and-facing-our-fears

- Why is mold or mildew considered a spiritual issue in Leviticus 14:39? – Bible Hub, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://biblehub.com/q/Why_is_mold_spiritual_in_Leviticus_14_39.htm

- Topical Bible: Blight and Mildew – Bible Hub, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://biblehub.com/topical/b/blight_and_mildew.htm

- Topical Bible: Blight, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://biblehub.com/topical/b/blight.htm

- What the Bible says about Divine Punishment, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.bibletools.org/index.cfm/fuseaction/Topical.show/RTD/cgg/ID/12781/Divine-Punishment.htm

- PLANTS – JewishEncyclopedia.com, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12203-plants

- Are Mushrooms Kosher? – Chabad.org, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/702285/jewish/Are-Mushrooms-Kosher.htm

- Mushrooms: Kosher Status, Blessing – Aish.com, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://aish.com/mushrooms-kosher-status-blessing/

- Mushrooms—Selfish, helpful, and rocket fuel – Torah Flora, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://torahflora.org/2008/08/mushrooms-fuel/

- Introduction to the Jewish Rules of Purity and Impurity, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/introduction-to-the-jewish-rules-of-purity-and-impurity/

- Purity and Impurity in Ancient Israel and Early Judaism – Jewish Studies – Oxford Bibliographies, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/abstract/document/obo-9780199840731/obo-9780199840731-0178.xml

- Purity and Impurity in Leviticus – The Bible Project, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://bibleproject.com/podcasts/purity-and-impurity-leviticus/

- Gardens of the Spirit: Land, Text and Ecological Hermeneutics in Jewish Mystical Sources, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://shc.stanford.edu/arcade/publications/dibur/unusual-gardens-towards-poetics-cultivated-earth/gardens-spirit-land-text

- (PDF) BIBLICAL CHRISTIAN WORLDVIEW ON POST-HARVEST PATHOGENIC FUNGI IN THE TRADITIONAL MARKET CORN SEEDS – ResearchGate, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352854615_BIBLICAL_CHRISTIAN_WORLDVIEW_ON_POST-HARVEST_PATHOGENIC_FUNGI_IN_THE_TRADITIONAL_MARKET_CORN_SEEDS

- Fungi and the Flood | National Center for Science Education, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://ncse.ngo/fungi-and-flood

- Plants of the Bible – Silene, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.silene.ong/en/documentation-centre/plants-of-the-bible

ADDENDUM

The ‘Erev Rav’ of Sinai: A Social Cognate of Foreign Influence and Internal Corruption

Introduction: The Foreigner Within

The formation of ancient Israel as a covenantal community was predicated on a principle of separation—a theological and social demarcation from the surrounding nations and their religious practices.1 This anxiety surrounding foreign influence is a recurring theme in the Tanach, where intermingling with other peoples is often depicted as a direct threat to Israel’s spiritual integrity and its unique relationship with God.1 While external enemies posed a physical threat, the more insidious danger was the “foreigner within,” an element that could corrupt the nation from the inside. The archetypal representation of this internal threat is the erev rav (עֵרֶב רַב), the “mixed multitude” that accompanied the Israelites out of Egypt.3

Mentioned explicitly in Exodus 12:38, the identity of this group is a subject of considerable debate. Interpretations range from Egyptian converts and the offspring of intermarriages to other enslaved peoples who seized the opportunity to escape bondage.5 Regardless of their precise origins, the erev rav functions within the biblical narrative and subsequent rabbinic tradition as a persistent source of spiritual contagion. They are consistently identified as the instigators of Israel’s most significant rebellions in the wilderness, most notably the sin of the Golden Calf and the craving for the foods of Egypt.3 In this capacity, the erev rav serves as a powerful social cognate to the corrupting forces of the fungal kingdom, embodying the principles of internal decay and external pollution that threaten the sanctity of the holy community.

The Golden Calf: An External Contagion of Idolatry

The most catastrophic spiritual failure during the wilderness journey was the worship of the Golden Calf, an event that occurred a mere forty days after the revelation at Sinai.10 While the entire nation bears responsibility, rabbinic tradition, particularly the Zohar, overwhelmingly identifies the erev rav as the primary architects of this rebellion.3 According to these interpretations, the “mixed multitude” included Egyptian sorcerers and magicians who, steeped in their native religious practices, were drawn not to God’s power but to what they perceived as Moses’s superior magic.6

When Moses’s return from the mountain was delayed, it was this group that exploited the people’s fear and uncertainty.12 Their Egyptian background provides a crucial context for the specific form of the idol. The worship of a bull, such as the Apis bull, was a central feature of Egyptian religion, representing fertility and divine power.13 By fashioning a calf, the erev rav introduced a foreign, idolatrous contagion directly into the heart of the Israelite camp. They acted as an external pollutant, analogous to the fungal tzaraat that could infect a house from without, rendering it ritually impure and requiring radical purification.5

The Zohar names the leaders of the plot as Yunus and Yumbrus, sons of the sorcerer Balaam, and suggests that the calf was animated through magical arts.5 It was the erev rav who then proclaimed, “This is your god, O Israel, who brought you out of the land of Egypt!” (Exodus 32:4).10 The subsequent punishment, in which the Levites executed 3,000 instigators, is understood as a necessary act of spiritual cleansing, a purging of the foreign contagion to restore the sanctity of the covenant community.5

The Craving for Meat: The Leaven of Discontent

If the Golden Calf represents an external contagion, the incident of craving meat in Numbers 11 illustrates the erev rav‘s function as an internal, fermenting agent of discontent. The narrative is explicit in identifying the source of the complaint: “Now the mixed multitude who were among them yielded to intense craving; so the children of Israel also wept again and said: ‘Who will give us meat to eat?’” (Numbers 11:4).15

The rebellion does not originate with the Israelites themselves but with the “rabble” or “misfits” among them.15 Their desire for the fish, cucumbers, melons, leeks, onions, and garlic of Egypt acts as a spiritual leaven (chametz). A small, localized pocket of discontent and worldly desire quickly permeates the entire community, causing the “whole lump” of Israel to rise up in complaint against God’s provision of manna.9 This episode serves as a perfect social parallel to the mycological process of fermentation, where a hidden agent sours and transforms the whole. The erev rav, with their lingering attachments to their former life, introduce a corrupting influence that turns the people’s hearts back toward Egypt and away from the promise of God.

The Enduring Symbol of the Internal Enemy

In later Jewish mystical and kabbalistic thought, the erev rav transcends its historical context to become an enduring symbol for any internal force that undermines the spiritual integrity of Israel.14 The Zohar explains that the erev rav are the cause of most problems that affect the Jewish people, and the 16th-century mystic Isaac Luria taught that their souls are reincarnated in every generation.3

In this expanded understanding, the erev rav are not necessarily non-Jews, but can be those from within the community who appear to be leaders but are inwardly corrupt.5 They are identified by their negative traits: creating strife, pursuing selfish desires and honor, and feigning righteousness.14 They are the “false leaders” who wrest control from genuine teachers and guide the people astray.3 This concept solidifies the role of the erev rav as the ultimate internal enemy, one who operates through deception from within the camp.14

Conclusion

The biblical and post-biblical portrayal of the erev rav provides a compelling social and theological parallel to the symbolism of the fungal kingdom. They function as the human embodiment of a corrupting agent within the body of Israel. Through their instigation of the Golden Calf, they act as an external contagion of foreign idolatry, a spiritual tzaraat that defiles the community’s holiness. Through their craving for Egyptian food, they act as an internal leaven, a spiritual chametz that ferments discontent and rebellion from within. The narrative of the erev rav thus serves as a powerful allegory for the ever-present danger that unassimilated and spiritually misaligned elements pose to the purity and mission of a covenantal people. They are the ultimate cognate for the unseen forces of decay, a constant reminder that the greatest threats to a holy community often arise not from the enemy without, but from the “mixed multitude” within.

References

5 Israel’s Greatest Enemy: The Erev Rav. (n.d.). Mayim Achronim. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.mayimachronim.com/israels-greatest-enemy-the-erev-rav/

3 Erev Rav. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erev_Rav

7 The Erev Rav- Then and Now. (2015, March 26). The Times of Israel Blogs. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-erev-rav-then-and-now/

4 Erev Rav: A Mixed Multitude of Meanings. (n.d.). TheTorah.com. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.thetorah.com/article/erev-rav-a-mixed-multitude-of-meanings

6 The Erev Rav. (n.d.). OU Torah. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://outorah.org/p/142746/

9 Parashat Ki Tisa II – The Erev Rav. (n.d.). 13petals.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.13petals.org/erev-rav/

12 Boshesh. (n.d.). Ohr Somayach. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://ohr.edu/8776

11 Scapegoats and the Erev Rav. (2023, March 13). Alyth. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.alyth.org.uk/sermons-writings/publication/scapegoats-and-the-erev-rav/

10 What Was the Golden Calf? (n.d.). Chabad.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/3613047/jewish/What-Was-the-Golden-Calf.htm

16 “It’s the Jews”: The Erev Rav and the Golden Calf. (2025, March 9). The Hidden Orchard. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.thehiddenorchard.com/its-the-jews-the-erev-rav-and-the-golden-calf/

14 The Erev Rav. (n.d.). Torah.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://torah.org/torah-portion/perceptions-5781-bo/

13 The Influence of Ancient Egyptian Civilization on Israeli Religious Thought. (n.d.). Horus Academy. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://horus-academy.com/the-influence-of-ancient-egyptian-civilization-on-israeli-religious-thought/

1 Foreigners in the Old Testament. (2019). SciELO South Africa. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext\&pid=S0259-94222019000300013

17 The “mixed multitude” of Exodus 12:38. (2015). Brill. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://brill.com/view/journals/hbth/34/2/article-p139_3.xml

18 Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). CGG. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.cgg.org/index.cfm/library/article/id/399/mixed-multitude.htm

19 A Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). 119 Ministries. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://119ministries.com/119-blog/a-mixed-multitude/

20 Who Were The Mixed Multitude of the Exodus? (2016, February 16). My Morning Meditations. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://mymorningmeditations.com/2016/02/16/who-were-the-mixed-multitude-of-the-exodus/

8 Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). Bible Hub. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://biblehub.com/topical/m/mixed_multitude.htm

2 The Women of Solomon. (n.d.). Jewish Women’s Archive. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/women-of-solomon-bible

21 Solomon. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solomon

5 Israel’s Greatest Enemy: The Erev Rav. (n.d.). Mayim Achronim. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.mayimachronim.com/israels-greatest-enemy-the-erev-rav/

3 Erev Rav. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erev_Rav

7 The Erev Rav- Then and Now. (2015, March 26). The Times of Israel Blogs. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-erev-rav-then-and-now/

4 Erev Rav: A Mixed Multitude of Meanings. (n.d.). TheTorah.com. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.thetorah.com/article/erev-rav-a-mixed-multitude-of-meanings

6 The Erev Rav. (n.d.). OU Torah. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://outorah.org/p/142746/

9 Parashat Ki Tisa II – The Erev Rav. (n.d.). 13petals.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.13petals.org/erev-rav/

12 Boshesh. (n.d.). Ohr Somayach. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://ohr.edu/8776

11 Scapegoats and the Erev Rav. (2023, March 13). Alyth. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.alyth.org.uk/sermons-writings/publication/scapegoats-and-the-erev-rav/

10 What Was the Golden Calf? (n.d.). Chabad.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/3613047/jewish/What-Was-the-Golden-Calf.htm

16 “It’s the Jews”: The Erev Rav and the Golden Calf. (2025, March 9). The Hidden Orchard. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.thehiddenorchard.com/its-the-jews-the-erev-rav-and-the-golden-calf/

14 The Erev Rav. (n.d.). Torah.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://torah.org/torah-portion/perceptions-5781-bo/

13 The Influence of Ancient Egyptian Civilization on Israeli Religious Thought. (n.d.). Horus Academy. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://horus-academy.com/the-influence-of-ancient-egyptian-civilization-on-israeli-religious-thought/

1 Foreigners in the Old Testament. (2019). SciELO South Africa. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext\&pid=S0259-94222019000300013

17 The “mixed multitude” of Exodus 12:38. (2015). Brill. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://brill.com/view/journals/hbth/34/2/article-p139_3.xml

18 Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). CGG. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.cgg.org/index.cfm/library/article/id/399/mixed-multitude.htm

19 A Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). 119 Ministries. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://119ministries.com/119-blog/a-mixed-multitude/

20 Who Were The Mixed Multitude of the Exodus? (2016, February 16). My Morning Meditations. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://mymorningmeditations.com/2016/02/16/who-were-the-mixed-multitude-of-the-exodus/

8 Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). Bible Hub. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://biblehub.com/topical/m/mixed_multitude.htm

2 The Women of Solomon. (n.d.). Jewish Women’s Archive. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/women-of-solomon-bible

5 Israel’s Greatest Enemy: The Erev Rav. (n.d.). Mayim Achronim. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.mayimachronim.com/israels-greatest-enemy-the-erev-rav/

3 Erev Rav. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erev_Rav

7 The Erev Rav- Then and Now. (2015, March 26). The Times of Israel Blogs. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-erev-rav-then-and-now/

4 Erev Rav: A Mixed Multitude of Meanings. (n.d.). TheTorah.com. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.thetorah.com/article/erev-rav-a-mixed-multitude-of-meanings

6 The Erev Rav. (n.d.). OU Torah. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://outorah.org/p/142746/

9 Parashat Ki Tisa II – The Erev Rav. (n.d.). 13petals.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.13petals.org/erev-rav/

12 Boshesh. (n.d.). Ohr Somayach. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://ohr.edu/8776

11 Scapegoats and the Erev Rav. (2023, March 13). Alyth. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.alyth.org.uk/sermons-writings/publication/scapegoats-and-the-erev-rav/

10 What Was the Golden Calf? (n.d.). Chabad.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/3613047/jewish/What-Was-the-Golden-Calf.htm

16 “It’s the Jews”: The Erev Rav and the Golden Calf. (2025, March 9). The Hidden Orchard. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.thehiddenorchard.com/its-the-jews-the-erev-rav-and-the-golden-calf/

14 The Erev Rav. (n.d.). Torah.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://torah.org/torah-portion/perceptions-5781-bo/

13 The Influence of Ancient Egyptian Civilization on Israeli Religious Thought. (n.d.). Horus Academy. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://horus-academy.com/the-influence-of-ancient-egyptian-civilization-on-israeli-religious-thought/

1 Foreigners in the Old Testament. (2019). SciELO South Africa. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext\&pid=S0259-94222019000300013

17 The “mixed multitude” of Exodus 12:38. (2015). Brill. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://brill.com/view/journals/hbth/34/2/article-p139_3.xml

18 Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). CGG. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.cgg.org/index.cfm/library/article/id/399/mixed-multitude.htm

19 A Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). 119 Ministries. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://119ministries.com/119-blog/a-mixed-multitude/

20 Who Were The Mixed Multitude of the Exodus? (2016, February 16). My Morning Meditations. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://mymorningmeditations.com/2016/02/16/who-were-the-mixed-multitude-of-the-exodus/

8 Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). Bible Hub. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://biblehub.com/topical/m/mixed_multitude.htm

2 The Women of Solomon. (n.d.). Jewish Women’s Archive. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/women-of-solomon-bible

5 Israel’s Greatest Enemy: The Erev Rav. (n.d.). Mayim Achronim. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.mayimachronim.com/israels-greatest-enemy-the-erev-rav/

3 Erev Rav. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erev_Rav

7 The Erev Rav- Then and Now. (2015, March 26). The Times of Israel Blogs. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-erev-rav-then-and-now/

4 Erev Rav: A Mixed Multitude of Meanings. (n.d.). TheTorah.com. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.thetorah.com/article/erev-rav-a-mixed-multitude-of-meanings

6 The Erev Rav. (n.d.). OU Torah. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://outorah.org/p/142746/

9 Parashat Ki Tisa II – The Erev Rav. (n.d.). 13petals.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.13petals.org/erev-rav/

12 Boshesh. (n.d.). Ohr Somayach. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://ohr.edu/8776

11 Scapegoats and the Erev Rav. (2023, March 13). Alyth. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.alyth.org.uk/sermons-writings/publication/scapegoats-and-the-erev-rav/

10 What Was the Golden Calf? (n.d.). Chabad.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/3613047/jewish/What-Was-the-Golden-Calf.htm

16 “It’s the Jews”: The Erev Rav and the Golden Calf. (2025, March 9). The Hidden Orchard. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.thehiddenorchard.com/its-the-jews-the-erev-rav-and-the-golden-calf/

14 The Erev Rav. (n.d.). Torah.org. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://torah.org/torah-portion/perceptions-5781-bo/

13 The Influence of Ancient Egyptian Civilization on Israeli Religious Thought. (n.d.). Horus Academy. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://horus-academy.com/the-influence-of-ancient-egyptian-civilization-on-israeli-religious-thought/

1 Foreigners in the Old Testament. (2019). SciELO South Africa. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext\&pid=S0259-94222019000300013

17 The “mixed multitude” of Exodus 12:38. (2015). Brill. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://brill.com/view/journals/hbth/34/2/article-p139_3.xml

18 Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). CGG. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.cgg.org/index.cfm/library/article/id/399/mixed-multitude.htm

19 A Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). 119 Ministries. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://119ministries.com/119-blog/a-mixed-multitude/

20 Who Were The Mixed Multitude of the Exodus? (2016, February 16). My Morning Meditations. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://mymorningmeditations.com/2016/02/16/who-were-the-mixed-multitude-of-the-exodus/

8 Mixed Multitude. (n.d.). Bible Hub. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://biblehub.com/topical/m/mixed_multitude.htm

2 The Women of Solomon. (n.d.). Jewish Women’s Archive. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/women-of-solomon-bible

15 Numbers 11:4-6. (n.d.). Bible.com. Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://www.bible.com/bible/compare/NUM.11.4-6

Works cited

- The ‘foreigner in our midst’ and the Hebrew Bible – SciELO South Africa, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext\&pid=S0259-94222019000300013

- Women of Solomon: Bible | Jewish Women’s Archive, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/women-of-solomon-bible

- Erev Rav – Wikipedia, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erev_Rav

- Erev Rav: A Mixed Multitude of Meanings – TheTorah.com, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.thetorah.com/article/erev-rav-a-mixed-multitude-of-meanings

- Israel’s Greatest Enemy: The Erev Rav | Mayim Achronim, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.mayimachronim.com/israels-greatest-enemy-the-erev-rav/

- Mix – Multitude Mire – Shira Smiles on Parsha – OU Torah, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://outorah.org/p/142746/

- THE EREV RAV: then and now | Allen S. Maller – The Blogs, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-erev-rav-then-and-now/

- Topical Bible: Mixed Multitude, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://biblehub.com/topical/m/mixed_multitude.htm

- Parashat Ki Tisa II – The Erev Rav – 13 Petals, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.13petals.org/erev-rav/

- What Was the Golden Calf? – Chabad.org, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/3613047/jewish/What-Was-the-Golden-Calf.htm

- Scapegoats and the Erev Rav – Alyth, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.alyth.org.uk/sermons-writings/publication/scapegoats-and-the-erev-rav/

- What’s in a Word? – Ohr Somayach, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://ohr.edu/8776

- The Influence of Ancient Egyptian Civilization on Israeli Religious Thought |, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://horus-academy.com/the-influence-of-ancient-egyptian-civilization-on-israeli-religious-thought/

- The Erev Rav – Torah.org, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://torah.org/torah-portion/perceptions-5781-bo/

- The rabble with them began to crave other food, and … – Bible.com, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.bible.com/bible/compare/NUM.11.4-6

- “It’s the Jews”: The Erev Rav and the Golden Calf, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.thehiddenorchard.com/its-the-jews-the-erev-rav-and-the-golden-calf/

- The Mixed Multitude in Exodus 12:38: Glorification, Creation, and Yhwh’s Plunder of Israel and the Nations in – Brill, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://brill.com/view/journals/hbth/34/2/article-p139_3.xml

- The Mixed Multitude – Church of the Great God, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://www.cgg.org/index.cfm/library/article/id/399/mixed-multitude.htm

- A Mixed Multitude? – 119 Ministries, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://119ministries.com/119-blog/a-mixed-multitude/

- Who Were The Mixed Multitude of the Exodus? – Morning Meditations, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://mymorningmeditations.com/2016/02/16/who-were-the-mixed-multitude-of-the-exodus/

- Solomon – Wikipedia, accessed on October 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solomon