Part I: The Architecture of the Void – The Jewish Symbolic Order

1.1. Introduction: A Conflict of Registers

The persistent and often violent friction between Jewish thought and the broader currents of Western culture, a phenomenon historically designated as the “Jewish problem,” cannot be adequately comprehended through purely sociological, political, or even theological frameworks. These disciplines, while valuable, tend to analyze the conflict at the level of its manifest content—disputes over belief, economic competition, or political loyalties. A more profound analysis, however, reveals that this antagonism is not a historical contingency but a fundamental structural schism rooted in two irreconcilable modes of psychic organization and reality-construction. The conflict is one of registers. Using the psychoanalytic framework of Jacques Lacan, this report will argue that the “Jewish problem with Western culture” is the result of a structural incompatibility between a psychic economy that privileges the Symbolic order and one that is predicated upon the Imaginary.1

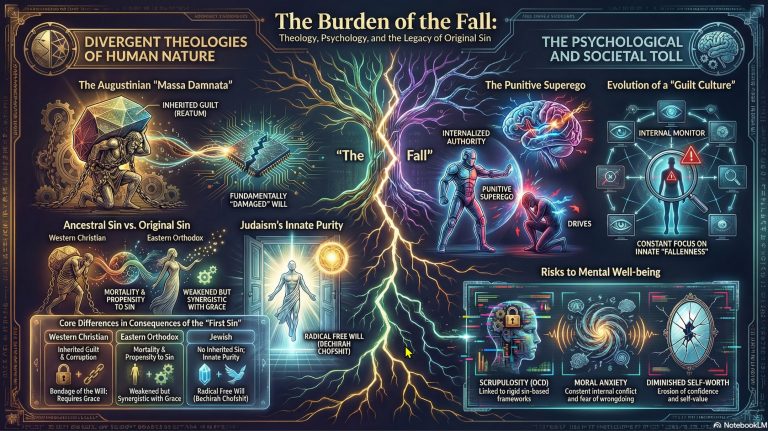

To undertake this analysis, it is essential to first define the Lacanian triad of the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real, the three elementary registers that constitute the human subject.2 The Imaginary is the realm of the ego, of images, mirrors, and fantasies. It is founded on the subject’s identification with a specular image, which gives rise to the sense of a whole, complete, and coherent self—the “I.” This register is characterized by dual relationships, rivalry, and a perpetual craving for images that can reflect and affirm this illusory sense of wholeness.1 The Imaginary and the Symbolic are perpetually interwoven, yet their relationship is also one of fundamental disjunction, a gap within the subject that can never be fully overcome.3

The Symbolic order, by contrast, is the realm of language, law, social structure, and what Lacan terms the “Name-of-the-Father.” It is a “language-mediated order of culture” that is determinant of subjectivity.4 Unlike the Imaginary’s logic of wholeness and identification, the Symbolic is a differential system of signifiers, where meaning arises not from a direct correspondence to a thing, but from the relationship of one signifier to another. This order inserts the subject into a pre-existing network of cultural, linguistic, and kinship structures, but it is always organized around a central lack, a void, or an absence. The law of the Symbolic forbids the subject’s immediate access to total satisfaction (jouissance) and structures desire around this fundamental prohibition.1

Finally, the Real is the most elusive of the three registers. It is the unspeakable, traumatic, and formless void that exists beyond and beneath the structuring capacities of the Imaginary and the Symbolic. It is not “reality” in the conventional sense, but raw, unmediated existence—an encounter with which can shatter the subject’s psychic integrity. The Real is that which “resists symbolization absolutely” and perpetually “stumbles” the Symbolic order, appearing as the irreducible residue of all attempts at articulation.1

This report posits that Jewish thought, in its foundational structures, represents a sophisticated and radical attempt to build a civilization upon the primacy of the Symbolic order. It is a system designed as a “bulwark” against the seductive lure of the Imaginary, and its central genius lies in its capacity to contain, rather than deny, the traumatic Real.1 Conversely, Western culture, in its dominant Roman and subsequent Christian formulations, is shown to be a civilization of the Imaginary, one whose power, theology, and social cohesion are predicated on spectacle, the deification of the visible image, and the ultimate fantasy of conquering the Real. The enduring conflict, therefore, is not between two sets of beliefs, but between two fundamentally different operating systems for constructing the self and the world: one organized around a central, structuring void, and the other organized around a central, captivating spectacle.

1.2. The Law Against the Image: The Symbolic as Bulwark

The characterization of Jewish thought as a system founded upon the Symbolic is not a metaphorical flourish but a description of its core operational mechanics. From its scriptural foundations to its legal superstructure, the tradition deploys a series of sophisticated mechanisms designed to subordinate the Imaginary register—the realm of the image and the ego—to the abstract authority of the Symbolic—the realm of language and the Law.1 This constitutes a profound “bulwark against the Imaginary,” a systematic resistance to the logic of “seeing is believing” that defines Imaginary captation.1

The first line of this defense is embedded in the very technology of its sacred text: the nature of Biblical Hebrew as an ancient abjad. An abjad is a script composed primarily of consonants, requiring the reader to supply the vowels to produce meaning. This structural feature has profound psychoanalytic implications. It renders passive visual consumption impossible; one cannot simply look at the text and receive its meaning as one would an image. To read the text is to be forced out of the passive role of the spectator and into the active role of the interpreter. More importantly, the ability to supply the correct vowels is not an innate skill but one that requires prior initiation into the Symbolic order of the mesorah, the oral tradition of law and interpretation. The text insists that meaning is not inherent in the visible marks on the page (the Imaginary) but is unlocked only through participation in the abstract system of the Law that governs it.1 This structure fundamentally de-privileges the eye in favor of the ear and the intellect, grounding meaning in a pre-existing linguistic and legal tradition rather than in immediate, specular evidence.

This textual bulwark is fortified and expanded into a totalizing life-system by Halacha (Jewish law). Halacha is described as the “ultimate expression of the Symbolic order”.1 It is an all-encompassing “fence” of words, rituals, and legal structures designed to mediate every moment of human existence, from waking to sleeping, from eating to commerce. Its function is to interpose the grid of the Symbolic between the subject and the immediacy of their drives and the world. Rather than acting on spontaneous feeling or desire, the subject of Halacha must constantly refer their actions to the abstract code of the Law. This system finds a parallel in the general psychoanalytic understanding of religious practice as a mechanism for controlling and sublimating unconscious wishes and impulses.6 However, within the Lacanian framework, its primary function is to continuously assert the primacy of the Symbolic register over the Imaginary, structuring reality through a shared, abstract code rather than through individualistic, image-based fantasies.

The most explicit and foundational articulation of this principle is found in the Decalogue, specifically in the Second Commandment’s absolute prohibition against idolatry. In his seminar on the ethics of psychoanalysis, Lacan himself identifies this moment as crucial. The prohibition against making a “graven image” is the foundational act of “barring the realm of the image”.7 It is the explicit legal codification of the principle that the divine, the ultimate source of authority and meaning, cannot and must not be represented in the Imaginary register. This “elimination of the function of the imaginary,” Lacan argues, presents itself as “the principle of the relation to the symbolic… that is to say, to speech”.7 The commandment establishes a God who can only be related to through language, law, and covenant—the very materials of the Symbolic.

This is anchored by the nature of the divine name itself. The untranslatable four-letter name, YHVH, functions as what Lacan calls the master signifier, or $S_1$. The $S_1$ is a signifier without a signified; it does not “mean” anything in the conventional sense. Instead, it is the pure, nonsensical signifier that retroactively anchors the entire chain of all other signifiers, giving them their consistency and meaning.7 The divine declaration “I am that I am” crystallizes this function: it is a statement of pure being that refuses to be pinned down to any specific image or attribute. This abstract, unnamable presence stands in stark opposition to the pantheons of the ancient world, which were populated by deities with distinct personalities, visual representations, and mythologies—figures ripe for Imaginary identification. The Jewish system, through its aniconic core, thus establishes its authority in the abstract, “empty” authority of the Symbolic order itself, a system of pure difference held in place by a master term that is itself a kind of void.1

1.3. The Traumatic Encounter: Sinai and the Irruption of the Real

While the Symbolic order of Jewish law provides a structure for mediating reality, it is a structure built in response to, and as a defense against, a foundational trauma. The source document argues that the revelation at Mount Sinai was not a serene moment of divine wisdom being peacefully imparted to humanity. Rather, the biblical texts describe it as a terrifying, overwhelming, and fundamentally traumatic event: a direct, unmediated encounter with the Lacanian Real.1 The descriptions of thunder, lightning, fire, and a sound so powerful that the people fear for their very lives—”Let not God speak with us, lest we die”—are textual evidence of a confrontation with something that shatters the psyche’s capacity for symbolization.1

This was not a communication within the Symbolic order; it was an irruption of the Real into the world, a moment of what Lacan calls jouissance—an unbearable pleasure/pain that the human ego cannot integrate or process.1 The Real, as that which lies beyond language and representation, disrupts the subject’s established notions of reality.5 The encounter at Sinai was precisely such a disruption. The first set of tablets, described as being “written with the finger of God,” were therefore not simply a list of laws. They were a material fragment of the Real itself, a piece of raw, unmediated divine presence made manifest. As such, they were impossible for a human subject, constituted within the fragile orders of the Imaginary and Symbolic, to handle.1

The Israelites’ reaction in the face of this trauma, particularly during the absence of their mediator, Moses, was a desperate regression to a more primitive and comforting psychic register. The construction of the Golden Calf was a mass flight from the formless, terrifying Real back to the controllable, consoling Imaginary.1 Unable to bear the abstract and overwhelming nature of the divine voice, the people demanded, “Make us a god we can see!”.1 The calf was a tangible, whole, non-threatening image—a fantasy object created to plug the unbearable hole opened by the encounter with the Real. It was a psychological screen erected to protect their sanity, an attempt to replace the traumatic void with a solid, graspable Imaginary object. This act exemplifies the ego’s fundamental defense mechanism: when faced with an unbearable truth, it scrambles to create a fantasy that can contain and neutralize it.

It is Moses’s response upon his return that constitutes the crucial, founding act of the Jewish Symbolic order. When he sees this regression into the Imaginary, he shatters the first tablets. This act is of paramount importance: he breaks the pure, unbearable Real.1 This shattering is what makes civilization possible. The unmediated Real is anti-social; it dissolves all structures. By breaking the tablets, Moses performs a necessary mediation. He transforms the unbearable fragment of the Real into a memory, a foundational trauma around which a symbolic system can be built. The second set of tablets, which Moses carves himself, represents this new reality. They are the Symbolic order proper: the law, mediated by human language, structure, and interpretation. They are a code that can be handled, studied, and lived with, unlike the first tablets, which could only be experienced as a shattering force.1 This founding narrative establishes the principle that the Symbolic order is not a reflection of a harmonious reality, but a necessary artifice constructed in the wake of a traumatic encounter with the Real.

1.4. Containing the Void: The Temple as Psycho-Architecture

The genius of the psychic system established by the Mosaic act is not that it represses or eliminates the traumatic Real, but that it structurally integrates it. The source document highlights a crucial detail: the fragments of the first, shattered tablets—the very remnants of the traumatic encounter with the Real—were not discarded. They were collected and preserved in the Ark of the Covenant, placed alongside the second, whole set of tablets, which represent the Symbolic order.1 This act is the psychoanalytic key to the entire structure. The Symbolic (the Law) is explicitly built to contain a fragment of the Real. The system acknowledges the trauma, the void, the unspeakable, and gives it a place at the very center of its structure. By doing so, it domesticates the Real without pretending to have vanquished it, creating a psychic edifice that is organized around an acknowledged lack rather than a feigned plenitude.1

This principle of a void-centered structure found its ultimate architectural expression in the Temples in Jerusalem. The entire Temple complex was a machine for mediating the relationship between the human and the divine, a series of concentric boundaries, symbolic gates, and intensifying rituals, all leading toward a single, terrifying center: the Kodesh HaKodashim, the Holy of Holies.1 Crucially, this center was empty. It contained nothing but the Ark of the Covenant, which itself held the void—the memory of the shattered Real. This “void at the center” represents the constitutive lack, what Lacan designates with the matheme $ \Phi $, that organizes the entire Symbolic system.1 The emptiness of the Holy of Holies served a vital structural function: it prevented any Imaginary object, be it an idol, an emperor, or any other specular figure, from filling that central gap and becoming a false, totalizing absolute. The High Priest’s annual entry into this space was a carefully staged and heavily mediated brush with the Real, surrounded by thick layers of Symbolic ritual (incense, prayers, specific vestments) to make the encounter survivable.1

This psychoanalytic reading can be profoundly enriched by the work of scholar Elliot Wolfson on Jewish mysticism, particularly his engagement with the themes of concealment and unconcealment. Wolfson’s analysis of Kabbalistic thought reveals a deep structure where ultimate reality is not a definable being but an event of presence that is always in excess of what is present.9 Truth, in this mystical hermeneutic, is often depicted as the “unconcealedness of the concealment of concealment”.10 The empty Holy of Holies is the perfect embodiment of this principle. It is a presence made overwhelmingly manifest through its absolute physical absence. The divine is not “in” the room; the divine is the emptiness of the room, an emptiness that structures the entire surrounding reality. What is given is given only as what is ungiven.9 The void is not a sign of God’s absence, but the very mode of God’s presence within a Symbolic system that forbids Imaginary representation. This convergence of Lacanian psychoanalysis and Kabbalistic meontology reveals a shared understanding of a reality founded not on solid presence, but on a dynamic interplay of presence and absence, disclosure and concealment. The Jewish Symbolic order, architecturally embodied in the Temple, is thus a system designed to live with, and draw meaning from, the foundational void that other systems seek to fill or deny.

Part II: The Civilization of the Spectacle – The Western Imaginary

2.1. The Roman Ego and the Indigestible Void

In stark structural opposition to the Jewish Symbolic order stands the Roman Empire, which the source document characterizes as the “ultimate civilization of the Imaginary”.1 Whereas the Jewish system was built on the abstract authority of text and an unseen God, Roman power was predicated on the concrete, visible, and spectacular. The logic of Rome was the logic of the image, the triumph of the ego-ideal made manifest for all to see. Its social and political cohesion was maintained through a constant procession of spectacles: the military triumph, where conquered peoples and booty were paraded through the streets; the gladiatorial games in the arena, which staged life and death as public entertainment; the visible might of the uniformed legion, a symbol of omnipresent force; and, most significantly, the deification of the Emperor, who served as the ultimate Imaginary ego, a figure with whom the collective Roman subject could identify.1

The religious dimension of the Roman world mirrored this Imaginary structure. Roman polytheism was a pantheon of images, a collection of deities with distinct visual forms, personalities, and narratives. This system was inherently absorptive; it could incorporate new, foreign gods into its pantheon so long as they could be represented visually and integrated into the existing Imaginary framework.1 A new statue could always be added to the collection.

It is within this context that the Jewish system proved to be, in the words of the source document, “fundamentally indigestible to the Roman ego”.1 The Jewish refusal to participate in the Roman Imaginary was not merely a matter of stubbornness or divergent belief; it was a structural incompatibility. To the Roman mind, a system centered on an unseen God was baffling. A religion based on an abstract Law rather than a divine personality was incomprehensible. And a Temple whose most sacred spot was, by design, empty, was a scandal and an absurdity. The Roman historian Tacitus, for instance, famously recorded his astonishment upon entering the conquered Temple in Jerusalem and finding the Holy of Holies to be vacuum, empty. This emptiness was not just a curiosity; it was a profound challenge to the Roman worldview. It represented a refusal of the very logic of specular power upon which the Empire was built. The Jewish system was a void that Rome could not assimilate, a signifier it could not translate into its Imaginary code.

The inevitable result of this clash of psychic structures was violence. The Roman destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE can thus be interpreted not simply as a military or political act of suppressing a rebellion, but as a profoundly psychoanalytic event. It was the Imaginary ego of Rome, enraged and baffled by a Symbolic order that fundamentally challenged its reality, attempting to violently annihilate that which it could not control.1 It was a desperate, physical attempt to destroy the void, to eradicate the structural lack that Rome could neither understand nor tolerate. By leveling the Temple, Rome sought to eliminate the architectural embodiment of the Symbolic order and its empty center, trying to prove, through overwhelming force, that only the visible, the tangible, and the spectacular held true power.

2.2. The Christian Conquest of the Real

Into the structural conflict between the Jewish Symbolic and the Roman Imaginary, a new and revolutionary proposition emerged: Christianity. Born within the Roman-Pagan world, Christianity offered a synthesis that spoke directly to the logic of the Imaginary while addressing the most profound and universal human trauma: the Real of death.1 As established, the Jewish Symbolic order did not claim to defeat death; rather, it contained the void of mortality at its center, managing the terror of the Real through the mediating structures of law and ritual. Christianity, however, proposed something radically different and far more appealing to a civilization of the spectacle: not the containment of the Real, but its conquest.1

The Resurrection is framed in the source document as the “ultimate Imaginary event”.1 It is the narrative of a visible, tangible body (the Imaginary) that triumphs over the ultimate, un-symbolizable trauma of death (the Real). This story offered the Roman world, a world already obsessed with spectacle and the deification of visible men, the most potent and captivating image of all: a man who defeats the void itself. The “Good News” was precisely that the central lack, the void that the Jewish system held open, had now been filled. The trauma of the Real, Christianity claimed, was no longer a thing to be managed by an abstract and difficult law, but a thing that had been defeated by faith in a visible, resurrected body.1

This analysis aligns with a broader Lacanian critique of religion. Lacan argued that religion functions to “excrete meaning” in order to conceal the traumatic problems and inconsistencies—the Real—that scientific and critical thought uncovers.11 Religion provides a master narrative that papers over the cracks in reality, sustaining a “concealment of the Real.” The Christian narrative of the Resurrection can be seen as the paradigmatic example of this function. It offers a totalizing meaning that resolves the ultimate contradiction of human existence—mortality. In psychoanalytic terms, it represents the ultimate fantasy: the fantasy that the Real no longer holds power.1

The power of this new system lay in its masterful use of the Imaginary signifier. The image, in the Lacanian sense, is a lure, a trap that captivates the subject.12 The cinematic or spectacular image, in particular, is characterized by a dual nature: it offers an unprecedented wealth of perceptual detail, yet it is simultaneously “stamped with unreality to an unusual degree”.13 The narrative of the resurrected Christ functions in precisely this way. It is an incredibly vivid and powerful image, yet its power derives from its status as an event that fundamentally breaks with reality. It is a spectacle that promises a reality free from the traumatic lack that defines actual existence. This new synthesis, which combined the Jewish preoccupation with a single, universal God with the Roman obsession with the divine image and spectacle, proved irresistible. It resolved the tension between the Symbolic and the Imaginary by offering a Symbolic system (Christian theology) whose central anchor was no longer a void, but the ultimate, triumphant Image.

2.3. The Ideological Function of the Social Imaginary

The analysis of the Western Imaginary, as embodied in Roman spectacle and Christian narrative, can be further deepened by integrating the work of the Lacanian philosopher Slavoj Žižek on the critique of ideology. For Žižek, ideology is not merely a set of false beliefs or “propaganda” that conceals the true state of affairs. Rather, ideology operates at a much deeper, unconscious level. It is a collective “ideological fantasy” that structures our social reality itself, allowing us to sustain our daily lives without being overwhelmed by the traumatic, antagonistic core—the Real—of our society.14 Ideology’s primary function is to provide a fantasy-screen that conceals the “menacing abyss of the Real” and reinforces the illusion of a coherent and harmonious social order.15

From this perspective, the Roman and Christian Imaginary orders can be understood as immensely powerful ideological fantasies. The spectacle of the Roman triumph, for example, was not just a celebration of military victory. It was an ideological performance that created a unifying image of the Empire as an all-powerful, coherent body, thereby suturing the real social divisions, resentments, and brutalities upon which that empire was built. It presented a fantasy of wholeness and order that concealed the chaotic violence at its core.

Similarly, the Christian narrative of the Resurrection and the formation of the Church as the mystical “Body of Christ” functions as a powerful ideological apparatus. It offers a universal community of believers, united in a single body, that transcends earthly divisions of class, ethnicity, and power. This image of a unified spiritual body acts as a fantasy-screen that obscures the real, persistent social antagonisms. As Žižek argues, ideology’s function is to paint a picture that blurs the “traumatic antagonism in the depths of the social order” and, crucially, the fact that this internal split can never be fully healed.15

The Jewish Symbolic order, by insisting on the permanence of the central void, fundamentally resists this ideological suturing. It is a system that refuses to provide a final, comforting image that would conceal the lack. Its insistence on an abstract law, its prohibition of images, and its preservation of the traumatic Real at its core all work against the formation of a seamless ideological fantasy. This is what makes it so problematic for a Western culture whose social cohesion relies on the very Imaginary and ideological mechanisms that Jewish thought structurally dismantles. The conflict is thus not just psycho-structural but also deeply political. The Western Imaginary functions to legitimize and reproduce existing power relations by providing a fantasy of social harmony, while the Jewish Symbolic, in its refusal of this fantasy, implicitly contains a critique of that ideological closure.14

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Psychoanalytic Registers in Jewish and Western Structures

| Feature | The Jewish Symbolic Order | The Western Imaginary Order (Roman/Christian) |

|---|---|---|

| Central Principle | The Word/Law (Symbolic) | The Image/Spectacle (Imaginary) |

| Nature of Deity | Abstract, Unnamable, Unseen (A Void) | Visible, Personified, Incarnate (An Image) |

| Source of Authority | Textual Law (Halacha), Covenant | Visible Power (Emperor), Resurrected Body (Christ) |

| Central Locus | Empty Holy of Holies (Constitutive Lack) | The Imperial Triumph, The Resurrected Christ (Filled Center) |

| Relation to the Real | Containment (Acknowledging the trauma/void) | Conquest / Denial (Fantasy of overcoming trauma/void) |

| Primary Sin/Failure | Idolatry (Submitting to the Imaginary) | Blasphemy / Heresy (Refusing the central Image) |

This comparative table distils the core structural opposition that has been developed throughout the preceding analysis. The logic of the Jewish Symbolic order and the Western Imaginary order are shown to be antithetical across every key dimension of their reality-constructing apparatus. The former is organized by absence, abstraction, and law, while the latter is organized by presence, spectacle, and image. This fundamental incommensurability is not a matter of differing opinions but of two distinct psychic operating systems. The Roman attempt to find a statue in the Holy of Holies, or the later Christian attempt to see the Jewish Law as a mere foreshadowing of the incarnate Christ, are both examples of a category error—an attempt to apply an Imaginary interpretive grid to a Symbolic phenomenon. This repeated failure of translation is a source of profound and persistent antagonism, generating the bafflement and frustration that ultimately fuels the violence directed at the system that refuses to be assimilated. The demand for a king “like all the nations” and the earlier construction of the Golden Calf, “a god we can see,” demonstrate that this pressure to regress from the difficult Symbolic to the comforting Imaginary has been an internal tension from the very beginning.1

Part III: The Abject and Its Terror – The Psychoanalytic Roots of Antisemitism

3.1. The Jew as a Structural Reminder

The structural dichotomy established between the Jewish Symbolic order and the Western Imaginary provides the necessary foundation for a psychoanalytic theorization of antisemitism. If the Western cultural edifice, in both its Roman and Christian forms, is an Imaginary fantasy of wholeness built upon the denial and repression of the traumatic Real, then the Jew assumes a profoundly unsettling structural position. The Jewish system, with its insistence on the abstract Law, its aniconic principle, and its enshrinement of a central void, becomes a living, breathing, structural reminder of precisely that which the Western Imaginary has sought to repress.1 The Jew, by their very existence as a subject of the Symbolic Law, represents the “lack at the center of their own systems”.1

This psycho-structural function resonates deeply with Sigmund Freud’s own attempts to analyze the unconscious roots of antisemitism. In his final work, Moses and Monotheism, Freud speculated that the “disagreeable, uncanny impression” made by the Jewish rite of circumcision was a key factor.16 For Freud, circumcision unconsciously evokes the “dreaded castration idea,” a reminder of a “primeval past which they would fain forget”.17 While Freud’s theory is rooted in his specific Oedipal framework, its underlying logic is homologous with the Lacanian analysis presented here. In both accounts, the Jew embodies a fundamental lack—castration, the void—that the Other wishes to deny in themselves. The physical mark of circumcision on the Jewish body becomes a signifier of this lack, a permanent and visible reminder of a symbolic cut that the Imaginary ego, in its fantasy of bodily wholeness, seeks to disavow. The Jew’s adherence to a Law that privileges abstraction and renunciation of instinct over pagan sensuality further reinforces this position, making the Jew a figure of the Symbolic Father who legislates against immediate gratification, thereby provoking the resentment of those who wish to remain in a more infantile, Imaginary state of being.9 The Jew, therefore, is not hated for what they do, but for what they represent: the irrefutable evidence of the lack upon which all identity is precariously built.

3.2. Powers of Horror: A Kristevan Deep Dive

To fully grasp the affective intensity of this reaction, it is necessary to move from the Lacanian framework of structural lack to the more visceral concept of the “abject,” developed by the psychoanalyst and philosopher Julia Kristeva. The source document introduces the abject as that which is violently cast out to create a “clean” identity, such as a corpse or bodily fluid.1 However, a deeper analysis of Kristeva’s work reveals a more complex and powerful theoretical tool. The abject is not merely the opposite of the clean or the proper; it is what precedes and threatens the very distinction between subject and object, self and other. The abject is what has been expelled from the body and the psyche to allow for the formation of a stable, bordered self, but it perpetually threatens to return. It is the primal repression, that which radically disturbs identity, system, and order because it does not respect borders, positions, or rules.19 It is the formless, the pre-symbolic, the archaic maternal, the corpse—all that which reminds the constituted subject of the chaotic, material Real from which it laboriously emerged and to which it will ultimately return.1 Abjection is, as Kristeva writes, a state of “perpetual danger” where the subject’s boundaries threaten to dissolve.20

Kristeva’s crucial contribution, particularly in her seminal work Powers of Horror, is to forge a direct link between the psychoanalytic dynamics of abjection and the cultural phenomenon of antisemitism.19 She argues that the xenophobe’s violent hatred of the Other is rooted in the primal horror of the abject. This horror is directed at that which is perceived as threatening the integrity of the self and the social body. Kristeva controversially suggests that there is an unconscious association between antisemitism and misogyny, rooted in their shared link to the abject. Both the archaic maternal body and the Jew come to occupy the position of the abject for the phobic subject.22 The maternal body is the site of the most primal abjection, the place where the boundary between self and other is not yet established. The Jew, for different structural reasons, comes to embody a similar threat to borders and purity for the Western Imaginary.

By insisting on the abstract Law and the “void” of the Real, the Jew becomes the abject of Western civilization.1 The Jew’s system is one of separation, distinction, and the maintenance of symbolic boundaries (e.g., dietary laws), which, paradoxically, makes the Jew appear to the Other as a foreign body that threatens the “purity” of the host culture. In a passage of profound significance, Kristeva notes that “the writings of the chosen people have selected a place, in the most determined manner, on that untenable crest of manness seen as symbolic fact—which constitutes abjection”.20 By so radically aligning with the Symbolic order and its inherent lack, the Jew comes to represent the very process of separation and boundary-formation that the Imaginary ego both relies upon and violently repudiates. The Jew is the border itself, and is therefore perceived as a constant threat to any fantasy of a borderless, “natural” wholeness.

3.3. From Hatred to Horror: Antisemitism as Existential Terror

The synthesis of these psychoanalytic concepts—the structural reminder of lack, and the visceral experience of the abject—allows for a radical reframing of antisemitism. It is not, at its core, a rational hatred based on competing interests, nor is it simple bigotry or prejudice. It is a profound existential terror.1 It is the violent, primal horror of an ego, constituted within the Imaginary, confronting the abjected Real that it has desperately and violently tried to expel in order to maintain its fantasy of being a “clean and proper” self.1 The antisemite’s rage is the terror of an identity built on the spectacle of wholeness when it is confronted with the irrefutable evidence of the void.

This transforms our understanding of antisemitic violence. It is not merely an act of aggression against a perceived enemy; it is a desperate, pathological, and ultimately futile attempt to shore up a fragile Imaginary identity. The violence is an effort to physically annihilate the reminder of the void, to destroy the “corpse” upon which the antisemite’s own sense of self is built.1 This explains the obsessive, “irrational” quality of antisemitic persecution. The goal is not just to defeat the Jew, but to purify the world of the principle the Jew represents.

This framework reveals antisemitism as a phobia in the strict psychoanalytic sense. The phobic object, for Lacan, is not what is truly feared. It is a contingent, often meaningless signifier that comes to stand in for a more fundamental, formless anxiety—the dread of castration, of the desire of the Other, of the lack in being itself.20 The phobic object serves to condense and localize this free-floating existential dread, giving it a name and a face. The Jew, for the historical and structural reasons outlined in this report, has become the paradigmatic phobic object for Western culture. The Jew condenses all the anxiety associated with lack, death, abstraction, intellectuality over sensuality, and the ultimate failure of the Imaginary to achieve a state of perfect, un-castrated wholeness.

This explains the notoriously protean and contradictory nature of antisemitic tropes. The Jew is simultaneously accused of being the arch-capitalist and the revolutionary communist, of being clannishly insular and rootlessly cosmopolitan, of being backwards and legalistic yet dangerously modern and intellectual. From a rational perspective, these accusations are nonsensical. From a psychoanalytic perspective, their contradictory nature is the key to their function. The specific content of the accusation is irrelevant. What matters is that the figure of the “Jew” functions as the screen onto which the culture projects everything it abjects from itself. The antisemite’s hatred is not a response to the real actions of Jews; it is a violent reaction to the void within themselves, a void that the figure of the Jew has come to symbolize. It is, as the source document concludes, a “profound, existential horror of the void”.1

Part IV: Contemporary Resonances and Theoretical Expansions

4.1. Beyond the Law: Jewissance and the Mystical Complication

The analysis thus far has relied on a necessary, if somewhat schematic, opposition between the Jewish Symbolic and the Western Imaginary. While this structural dichotomy is essential for understanding the core of the conflict, it risks presenting Jewish thought as a monolithic and exclusively austere legalism. To achieve a more nuanced understanding, it is crucial to complicate this model by acknowledging the powerful currents within Judaism that push beyond the strictures of the Symbolic Law and engage directly with ecstatic experience and the Real. The work of scholar Elliot R. Wolfson is indispensable here, particularly his playful yet profound neologism, Jewissance.18

Jewissance is a portmanteau that combines “Jew,” the French term for ecstatic, excessive pleasure-in-pain jouissance, and the French word for recognition, reconnaissance. The term points to a sense of pleasure, an ecstatic excess, and a profound rootedness experienced within Jewish life that cannot be fully contained or explained by the Symbolic order of Halacha alone.18 This dimension is most evident in the mystical traditions of Kabbalah and Hasidism. Kabbalah, with its intricate theosophy of divine emanations (sefirot), its focus on visionary experience, its daring use of sacred eroticism to describe the relationship between the divine and the human, and its conception of a dynamic, gendered deity, reintroduces a wealth of imagistic and ecstatic elements that resonate with the registers of the Imaginary and the Real. This mystical stream reveals that the tension between the registers is not only an external conflict between Judaism and the West, but a dynamic and productive tension within Jewish thought itself.24

Wolfson’s analysis of circumcision provides a powerful example of this internal complexity. On one level, circumcision is the ultimate mark of the Symbolic covenant, the physical inscription of the Law onto the body. Yet, as Wolfson demonstrates through his readings of Kabbalistic texts, the mystics saw the exposed corona of the phallus as representing the Shekhinah, the feminine aspect of the divine.9 This interpretation transforms the ultimate signifier of patriarchal law and symbolic castration into a site of androgynous complexity, a paradoxical convergence of absence and presence, concealment and disclosure. The phallus, the signifier of the Symbolic order, is revealed to contain its feminine other within itself. This mystical hermeneutic, which Wolfson describes as a “meontology” where reality is gauged from the “nonbeing of withdrawal,” shows that even the most concrete sign of the Law is fraught with its own internal void and complexity.9 This recognition does not invalidate the primary thesis of this report, but it enriches it, showing that the Jewish system is not a static legal code but a dynamic tradition that constantly negotiates the relationship between its Symbolic structure and the Imaginary and Real excesses that structure can never fully contain.

4.2. Segregation, the Universal, and the “Not-All”

The structural position of the Jew as an indigestible element within the Western Imaginary can be further illuminated and brought into a contemporary political context through Lacan’s later work on social bonds and segregation. Lacan provocatively argued that universalizing discourses—systems that claim to apply to everyone and create a unified “all” (tout)—inevitably and structurally produce segregation as their byproduct.26 The more a system insists on a universal logic, whether it be the logic of the global market, scientific progress, or a universalizing religion, the more violently it must reject, expel, or quarantine that which does not fit its logic. This excluded element is what Lacan termed the “not-all” (pas-tout).26

For Lacan, the “Jewish Question” serves as the historical paradigm for this process of segregation. He prophesied that the extension of scientific and market universalism would lead to an “increasingly hardline extension of judicial acts of segregation,” with the Nazi concentration camps serving as a horrifying premonition of this future.26 In his framework, the Jew, alongside the woman and the psychoanalyst, occupies the structural position of the “not-all.” These figures resist being wholly captured by the universalizing logic of the master’s discourse. The woman, in Lacan’s theory of sexuation, is “not-all” submitted to the phallic function that defines the Symbolic order. The psychoanalyst operates from a position that subverts the dominant discourses of the university or the master. And the Jew, as has been argued throughout this report, represents a system that refuses the universalizing Imaginary of the West.

Lacan interprets racism and segregation as a “rejection of the jouissance of the Other”.26 The universal system demands a homogenization of enjoyment, a standardized way of being. The “not-all” figure is perceived as possessing a unique, singular, and secret jouissance that resists this standardization. The antisemite’s fantasy is obsessed with this supposed secret Jewish pleasure, power, or knowledge. This reframes the “Jewish problem with Western culture” in a starkly contemporary light. It is not an ancient religious dispute but the paradigmatic case of how modern, universal systems produce their own internal points of exclusion. The Jew’s insistence on maintaining a distinct identity without a nation-state for millennia (a point noted with interest by thinkers like Žižek in their critiques of Zionism 29), and on adhering to a particular Law in the face of universalizing empires and religions, makes the Jew the ultimate figure of the “not-all”—the exception that proves, and threatens, the universal rule.

4.3. Conclusion: The Enduring Split

This report has sought to demonstrate that the “Jewish problem with Western culture” is not a problem that can be “solved” through dialogue, assimilation, or political negotiation, because it is not, at its root, a problem of content. It is a structural schism between two fundamentally incommensurable psychic economies: a Jewish order founded on the primacy of the Symbolic and the containment of the Real, and a Western order predicated on the dominance of the Imaginary and the denial of the Real. The former is an architecture of the void, a system of meaning built around an acknowledged lack. The latter is a civilization of the spectacle, a system of identity built around a captivating and unifying image that conceals that same lack.

The consequences of this structural split are profound. It positions the Jewish system as a permanent, indigestible foreign body within the West—a constant, structural reminder of the void, castration, and abstraction that the Western Imaginary is constructed to disavow. This, in turn, transforms the Jew into the paradigmatic figure of the Kristevan abject, the object of a phobic terror that is far more primal and powerful than mere hatred or bigotry. Antisemitism, in this reading, is the violent convulsion of an Imaginary ego desperately attempting to expel the unbearable truth of its own lack, a truth that the figure of the Jew has come to embody.

This psycho-structural framework reveals a deep homology between the societal position of the Jew and that of the psychoanalyst. Lacan grouped them together as figures of the “not-all” for a reason.26 Both insist on an uncomfortable and disruptive truth. The analyst’s fundamental assertion is that the ego is not master in its own house, that our conscious sense of self is a fragile fiction built upon a turbulent unconscious structured by lack and desire.30 The Jew’s structural assertion, as analyzed here, is that the cultural order is not a harmonious whole, that our collective reality is not grounded in a divine presence or a natural plenitude, but is a Symbolic artifice built around a traumatic, central void. Both the analyst and the Jew are therefore “abject” figures who speak a truth that the dominant social order, which is governed by Imaginary fantasy and ideological closure, does not want to hear. The resistance to psychoanalysis and the persistence of antisemitism can thus be seen as stemming from the same source: the violent reaction of the Imaginary ego against any discourse that confronts it with the repressed Real.

Ultimately, this analysis provides a powerful, if unsettling, lens for understanding not only this specific historical antagonism but also a range of contemporary phenomena. The enduring tension between the Symbolic and the Imaginary plays out in the modern conflict between the rule of abstract law and the power of the media image; in the political battles between universal principles and identity politics based on visible markers; and in the relentless societal search for scapegoats onto whom the anxieties of economic instability, social fragmentation, and existential dread can be projected. The split is not out there, between “Jews” and “the West,” but is an internal, structural tension within Western consciousness itself. Acknowledging and understanding this enduring split is a crucial, if difficult, first step in any deep critique of our culture and its profound discontents.

Works cited

- The Real-Imaginary the containment and provocation of Terror.pdf

- LACANIAN PSYCHOANALYSIS AND PSYCHOLOGY OF RELIGION By Hercules Karampatos, MA, Cand. Ph.D. Abstract This is a study, at the core, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://epub.lib.uoa.gr/index.php/theophany/article/download/2376/2028

- The Imaginary and Symbolic of Jacques Lacan – DOCS@RWU, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://docs.rwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044\&context=saahp_fp

- The Symbolic – Wikipedia, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Symbolic

- The Real – Wikipedia, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Real

- Orthodox Judaism and Psychoanalysis: Toward Dialogue and Reconciliation, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8434261_Orthodox_Judaism_and_Psychoanalysis_Toward_Dialogue_and_Reconciliation

- Revelation: Lacan and the Ten Commandments, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.jcrt.org/archives/02.1/reinhard_lupton.shtml

- (PDF) The Subject of Religion: Lacan and the Ten Commandments – ResearchGate, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236783280_The_Subject_of_Religion_Lacan_and_the_Ten_Commandments

- Phallic Jewissance and the Pleasure of No Pleasure – Brill, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://brill.com/downloadpdf/book/edcoll/9789004345331/B9789004345331_011.pdf

- The Blogs: Elliot R. Wolfson Interview | Alexandre Gilbert #202 …, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/heidegger-kabbalah-and-unconcealedness/

- THE ETHICS OF SPEECH: LACAN, FRANCIS, AND THE REAL …, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.psychoanalytischeperspectieven.be/vol-42-1-2024/the-ethics-of-speech-lacan-francis-and-the-real

- 13. The Cinematic Signifier and the Imaginary – DOI, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv62hdcz.17

- THE IMAGINARY SIGNIFIER – Psychoanalysis and the Cinema, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://web.english.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Metz_Imaginary.pdf

- Psychoanalysis and politics: the theory of ideology in Slavoj Žižek – International Journal of Zizek Studies, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://zizekstudies.org/index.php/IJZS/article/download/125/125

- The Magician of Ljubljana – Azure – Ideas for the Jewish Nation, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://azure.org.il/article.php?id=165\&page=3

- Full article: Sigmund Freud’s Moses and Monotheism: A treatment of free association and stimulus words, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14725886.2025.2553043

- Sigmund Freud’s Moses and Monotheism : A treatment of free association and stimulus words – ResearchGate, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/395317456_Sigmund_Freud’s_Moses_and_Monotheism_A_treatment_of_free_association_and_stimulus_words

- Phallic Jewissance and the Pleasure of No Pleasure – Brill, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://brill.com/previewpdf/book/edcoll/9789004345331/B9789004345331_011.xml

- Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection – Julia Kristeva – Google Books, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://books.google.com/books/about/Powers_of_Horror.html?id=NCnoEAAAQBAJ

- Powers of Horror Quotes by Julia Kristeva – Goodreads, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.goodreads.com/work/quotes/1381198-pouvoirs-de-l-horreur-essai-sur-l-abjection

- Justice, injustice and the work of Julia Kristeva – Macquarie University, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/justice-injustice-and-the-work-of-julia-kristeva

- “LEGITIMATION OF HATRED OR INVERSION INTO LOVE” – Brill, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://brill.com/downloadpdf/book/edcoll/9789004496224/B9789004496224_s005.pdf

- Speaking the Unspeakable – UC Press E-Books Collection, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=kt4k4019nm\&chunk.id=ss1.16\&toc.id=ch04\&brand=ucpress

- Elliot Wolfson | Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://katz.sas.upenn.edu/who-we-are/elliot-wolfson

- Elliot Wolfson | Department of Religious Studies, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.religion.ucsb.edu/people/elliot-wolfson

- THE JEW, THE WOMAN AND THE PSYCHOANALYST: A MODEL OF NON-SEGREGATIVE SOCIAL BOND THE JEW, THE WOMAN AND THE PSYCHOANALYST – SciELO, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.scielo.br/j/agora/a/VtcntKTBPBVM7gyLBnDtH8Q/?lang=en

- THE JEW, THE WOMAN AND THE PSYCHOANALYST: A MODEL OF NON-SEGREGATIVE SOCIAL BOND – ScienceOpen, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=7a7db3cb-5903-4dbf-86d6-51eceec386f0

- THE JEW, THE WOMAN AND THE PSYCHOANALYST: A MODEL OF NON-SEGREGATIVE SOCIAL BOND – Redalyc, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.redalyc.org/journal/3765/376565652002/html/

- Lacanian Ink/Slavoj Zizek-Jean-Claude Milner-Marco Mauas/Lacan …, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.lacan.com/milma.htm

- Slavoj Zizek – Connections of the Freudian Field – Lacan.com, accessed on October 29, 2025, https://www.lacan.com/zizlacan3.htm

APPENDIX

Understanding Lacan’s Three Orders:

The Imaginary, Symbolic, and Real

Introduction: A Map to the Human Psyche

The psychoanalytic theories of Jacques Lacan can often seem dense, but this guide offers a clear breakdown of his three foundational concepts by examining how they are used in a psychoanalytic analysis of cultural structures. We will explore the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real—the “three elementary registers that constitute the human subject”—not as abstract definitions, but as tools for understanding a specific, provocative argument: that a fundamental conflict exists between a Symbolic-based order (exemplified by Jewish thought) and an Imaginary-based one (exemplified by Western culture). The examples of the Golden Calf and the revelation at Sinai are drawn from this analysis to demystify these terms and reveal their power in decoding the very structures of our reality.

1. The Imaginary: The Realm of the Ego and the Image

The Imaginary is the realm of the ego, of images, mirrors, and fantasies. It is founded on the subject’s identification with a “specular image,” which gives rise to the sense of a whole, complete, and coherent self—the “I.” The primary function of the Imaginary is to create the feeling of a unified self, but this feeling is ultimately an illusion.

This register is defined by three key characteristics that shape an individual’s sense of self:

- Illusory Wholeness: The sense of having a complete and coherent self is an illusion. It is created by identifying with an external image (like one’s reflection in a mirror) that appears more whole and coordinated than our internal experience.

- Dual Relationships & Rivalry: The Imaginary is fundamentally structured by competitive relationships. We relate to others by seeing them as either like us (someone to identify with) or as a rival who threatens our sense of self.

- Craving for Affirmation: Because the ego’s wholeness is an illusion, it perpetually seeks out images that can reflect and confirm this fragile sense of completeness.

A concrete example from the source text illustrates this process perfectly. The narrative of the Golden Calf is framed as a “mass flight from the formless, terrifying Real back to the controllable, consoling Imaginary.” Faced with the abstract nature of an unseen God (a Symbolic principle) and the trauma of a divine encounter, the people regressed. They demanded a tangible, visible god—a fantasy object created to “plug the unbearable hole” opened by the traumatic event. This act represents a flight away from the abstract Symbolic and a retreat into the comforting but illusory logic of the image.

The Imaginary’s illusion of wholeness is inherently fragile, constantly threatened by the fragmenting power of the Symbolic order—the world of language and law that cuts into our experience and assigns us a place within a system larger than ourselves.

2. The Symbolic: The World of Language and Law

The Symbolic order is the realm of language, law, social structure, and what Lacan terms the “Name-of-the-Father.” It is a “language-mediated order of culture” that is determinant of our subjectivity.

Unlike the Imaginary’s logic of wholeness, the Symbolic is a “differential system of signifiers,” meaning arises from the difference between words (e.g., ‘day’ only has meaning in contrast to ‘night’), not from any inherent connection between a word and the thing it describes. The Symbolic has two profound effects on the subject:

- It Creates the Subject The Symbolic order inserts the individual into a pre-existing network of cultural and linguistic structures. We are born into language and law; they shape who we are and how we understand our place in the world.

- It Introduces “Lack” The law of the Symbolic forbids our immediate access to total satisfaction (jouissance), and this forbidden zone is the territory of the Real. By structuring our desire around this fundamental prohibition, the Symbolic introduces “lack” as the central organizing principle of our psychic lives.

The prohibition against idolatry is the foundational evidence for a system designed as a “bulwark against the Imaginary.” The commandment against making a “graven image” is the ultimate act of “barring the realm of the image,” explicitly forbidding the representation of ultimate authority. This act is anchored by a divine name (YHVH) that functions as a “master signifier” (S_1)—a signifier without a signified that holds the entire chain of meaning in place. By forcing a relationship with an abstract authority that can only be known through language and law, this system establishes the primacy of the Symbolic.

The Symbolic order, a vast network of language and law, structures our reality, but it is a structure defined by what it excludes—a central void or “lack” that is, in fact, the trace of the unnamable Real itself.

3. The Real: The Traumatic and Unknowable Void

The Real is the most elusive of the three registers, described as “the unspeakable, traumatic, and formless void” that “resists symbolization absolutely.” It is the raw, unmediated existence that lies beyond the structuring capacities of both the Imaginary and the Symbolic.

To avoid common misunderstandings, it is crucial to clarify what the Real is and is not:

- It Is NOT Reality: The Real is not “reality” in the conventional sense. It is the raw, chaotic foundation of existence that our symbolic reality covers over.

- It IS Traumatic: A direct encounter with the Real is overwhelming. It can “shatter the subject’s psychic integrity” because it is a force beyond our capacity for language or representation.

According to the source’s analysis, the revelation at Mount Sinai is the foundational trauma upon which an entire Symbolic order was built. The biblical descriptions of thunder, lightning, and a sound so powerful the people feared death are evidence of a terrifying “irruption of the Real into the world.” This was a raw confrontation that shattered the psyche.

The first set of stone tablets, “written with the finger of God,” functioned as a “material fragment of the Real itself.” Impossible for a human to handle, they were an unbearable, unmediated presence. When Moses shattered these tablets, he performed a crucial act of mediation, transforming the “unbearable fragment of the Real into a memory, a foundational trauma around which a symbolic system can be built.” But the critical detail is what happened next: the broken pieces were not discarded. They were collected and placed inside the Ark of the Covenant alongside the second, whole tablets—the Symbolic Law. This profound act demonstrates that the Symbolic order is not meant to erase or defeat the Real. Rather, its primary function is to contain the memory of the traumatic encounter at its very core, domesticating the Real without ever pretending to have vanquished it.

These three registers are not isolated but are constantly interwoven, shaping our psychic lives in a complex and unending dynamic.

4. Synthesis: How the Three Orders Work Together

The Imaginary and Symbolic are “perpetually interwoven,” providing the fabric of our perceived reality. However, their relationship is also defined by a “fundamental disjunction,” a gap that can never be fully closed. This gap is where the Real makes itself known.

The following table synthesizes the core principles and functions of each register for easy comparison:

| Register | Core Principle | Primary Function |

| The Imaginary | The Image / The Ego | To create an illusory sense of a whole, coherent self (“I”) through identification with images. |

| The Symbolic | Language / The Law | To structure reality and desire through a shared system of signifiers, social rules, and prohibitions organized around a central lack. |

| The Real | The Traumatic Void | To exist as the unsymbolizable residue of existence that resists both the Imaginary and the Symbolic, appearing as a disruptive and shattering force. |

In Lacan’s view, our entire psychic life is the result of the constant, dynamic interplay between these three fundamental orders. Our sense of self (Imaginary) is given meaning and structure by the language and rules of society (Symbolic). Both of these systems function as a necessary, if fragile, defense against the terrifying, formless void that underpins all of existence (the Real).//