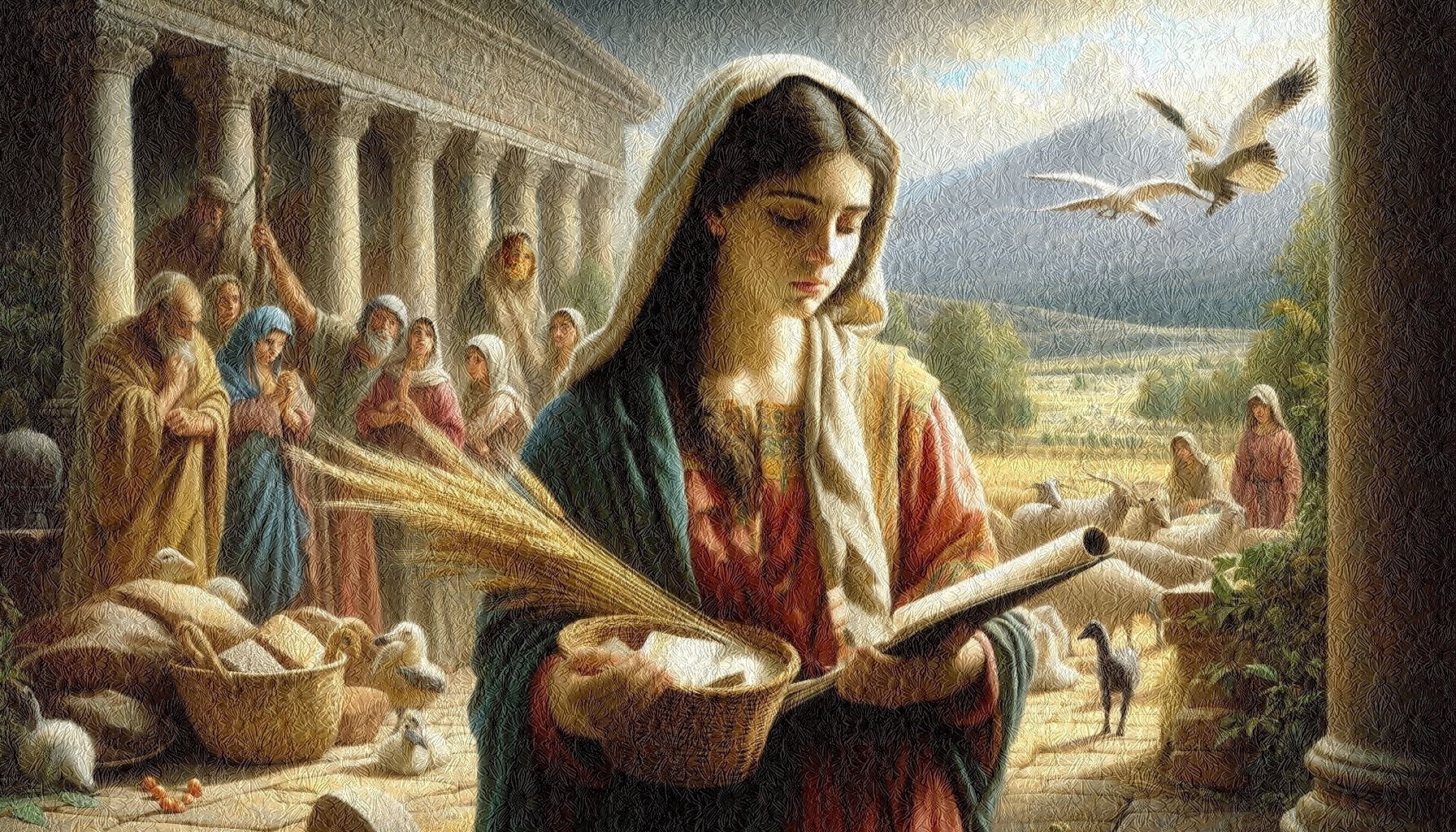

The Book of Rut(h) [רות] may initially seem to be a simple narrative focused on the devoted relationship between Ruth, a widow, and her mother-in-law Naomi, a closer examination reveals layers of nuanced complexity. Beneath its seemingly straightforward plotline lies an intricate exploration of profound themes such as loyalty, faith, and redemption. Delicate details—including Ruth’s status as a Moabite woman [Moab is the nation that refused to to offer bread and water to the Israelites coming up from Sinai (Deut. 23:5)] and Boaz’s position as the kinsman-redeemer—carry considerable weight and illuminate broader theological messages. These details question societal conventions around ethnicity, gender roles, and social hierarchies, amplifying the transformative power of steadfast love and divine providence.

This essay seeks to explore these intricate aspects of the Book of Ruth, demonstrating how its apparent simplicity cloaks a rich tapestry of spiritual insights. Examining the layered nuances of the Book of Ruth begins with considering Ruth’s identity as a Moabite. Her famous declaration, “Your people will be my people and your God my God” (Ruth 1:16), signifies not only a pledge of loyalty but also a courageous step over considerable cultural and religious barriers. In crossing these divides, Ruth challenges the ethnocentric attitudes pervasive in ancient Israelite society, illustrating that loyalty transcends ethnicity (Corn, 2024). Boaz’s acceptance and subsequent marriage to Ruth further magnifies this theme, representing an act of social redemption that goes beyond mere legal obligation.

As a kinsman-redeemer, Boaz acts within legal and social parameters, yet his willingness to embrace Ruth highlights divine grace at work through human agency. These subtleties form a complex narrative that affirms broader wisdom themes integral to Biblical literature. As noted by (Corn, 2024), the narrative conveys vital lessons on inclusivity and divine providence, setting forth human participation within God’s plan for redemption.

Positioned within the Ketuvim (Hagiographa), the Book of Ruth employs symbolic storytelling rather than direct divine revelations. According to (Shuchat, 2002), it serves as one of the premier examples of this narrative style within Hebrew literature. With the Prophet Samuel traditionally associated with its composition (Talmud Bavli – Bava Batra 14b)“… Samuel wrote his own book, the Book of Judges and the Book of Ruth…”, it is expected that symbolic elements permeate its structure in ways akin to prophetic texts. Indeed, the narrative employs linguistic symbolism to deepen its seemingly direct storyline. Subtleties emerge through specific word choices and phrasing, which carry layered meanings reinforcing its central themes. For instance, when Naomi instructs Ruth to meet Boaz at the threshing floor and to “uncover his feet” (Ruth 3:4), the term “feet” operates on dual levels, subtly indicating both vulnerability and an audacious plea for protection under Boaz’s guardianship (Shuchat, 2002). This clever use of language serves not only to enhance dramatic tension but also to depict socio-legal nuances within ancient Israelite customs regarding marriage and redemption.

The theme of “chesed” or loving-kindness also threads through these linguistic choices. It elevates acts of human kindness into reflections of divine grace—a connection powerfully portrayed in Ruth’s loyalty towards Naomi and Boaz’s compassionate response toward Ruth. Such multi-layered symbolic expressions prompt readers to look beyond initial interpretations, drawing them deeper into theological and philosophical contemplation on loyalty, faith, and divine mercy. Moreover, these linguistic nuances are matched by narrative oddities that bring additional layers to the story’s depiction of loyalty, faith, and redemption.

Symbolism in the Names

The Hebrew characters of Ruth’s name[ רות ] add up (via gematria) to 606. If you add the seven Laws of Noah, which are encumbant on all nations you get 613 – the number of commandments

Elimelech [אלימלך] means “may kingship come my way” or “God is my king” “…Both are possible understandings, since Elimelech was of the tribe of Judah,the tribe of monarchy. The sages say that Elimelech was a man of means, and therefore the term ish [lit. “a man”] is used, which usually denotes a man of stature…” (Suchat 2002 op.cit.)

Naomi [נעמי] comes from the word for pleasant

Bethlehem (literally “House of Bread”

Notable blatant symbolic names are Elimelech’s sons Machlon [Sickness] and Chilyon [decimation}

(Suchat 2002 op,cit.)

Ruth’s bold initiative in approaching Boaz stands out against the background of traditional gender expectations. Naomi’s guidance for Ruth to meet Boaz in such an intimate manner was unconventional and carried significant risk (Ruth 3:4). This calculated move highlights Ruth’s courage and establishes her as an active agent in her redemption story rather than a passive figure (Saxegaard, 2010). Boaz’s reaction furthers this exploration; rather than rebuffing Ruth’s overture, he responds with protective affirmation: “May you be blessed by the Lord…for you have made this last kindness greater than the first” (Ruth 3:10). This scene encapsulates a synthesis of personal integrity and communal obligation intertwined with chesed. Such interactions evoke thoughtful reflections on societal norms and divine will. As Gunkel (via Saxegaard) argues, these narrative anomalies act deliberately as literary devices intended to engage readers’ reflections on deeper societal norms and divine operations (Saxegaard, 2010). These eccentric plot developments thus serve dual functions—heightening reader engagement while also broadcasting significant theological truths about humanity’s role in divine plans for redemption.

In essence, the Book of Ruth offers more than just a recounting of familial devotion; it unravels a profound theological narrative enriched with cultural, symbolic, and spiritual layers. By examining these details through lenses of Ruth’s Moabite identity and Boaz’s redeeming actions, the story challenges entrenched prejudices and societal expectations while conveying broader lessons on loyalty, faithfulness, and redemption through divine and human intersections. Through its subtle oddities and linguistic intricacies, it captures complex theological motifs, encouraging readers to look deeper and appreciate its multi-dimensional wisdom.

- References

- Corn, B. (2024). The Book of Ruth: Its Didactic Wisdom Themes.

- Shuchat, R. B. (2002). The use of symbolism and hidden messages in the Book of Ruth. Jewish Bible Quarterly, 30(2), 110-117.

- Saxegaard, K. M. (2010). Character complexity in the Book of Ruth (Vol. 47). Mohr Siebeck.