See our YouTube Channel for a Summary and Overview

The Forensic Premise

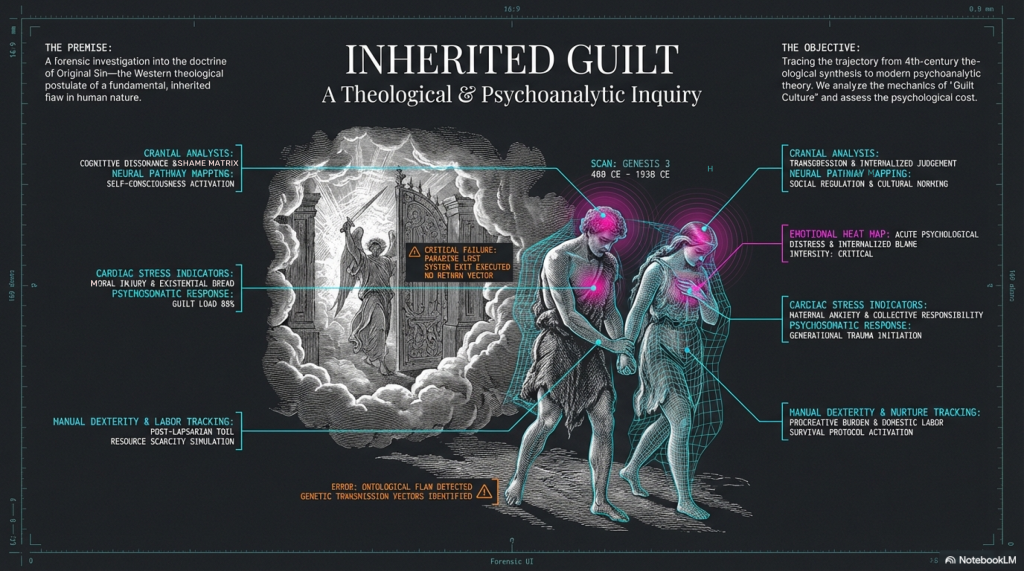

We begin with a “forensic investigation” into one of Western theology’s most pervasive postulates: Original Sin. This slide establishes a high-stakes clinical tone, framing the human condition as a crime scene where an “ontological flaw” has been detected. We see the objective clearly defined—to trace how a 4th-century theological synthesis evolved into modern psychoanalytic theory. The data points here are startling; the “Guilt Load” is calculated at 85%, and the system warns of “No Return Vector,” suggesting that once this doctrine is internalized, the psychological exit to a state of primal innocence is closed.

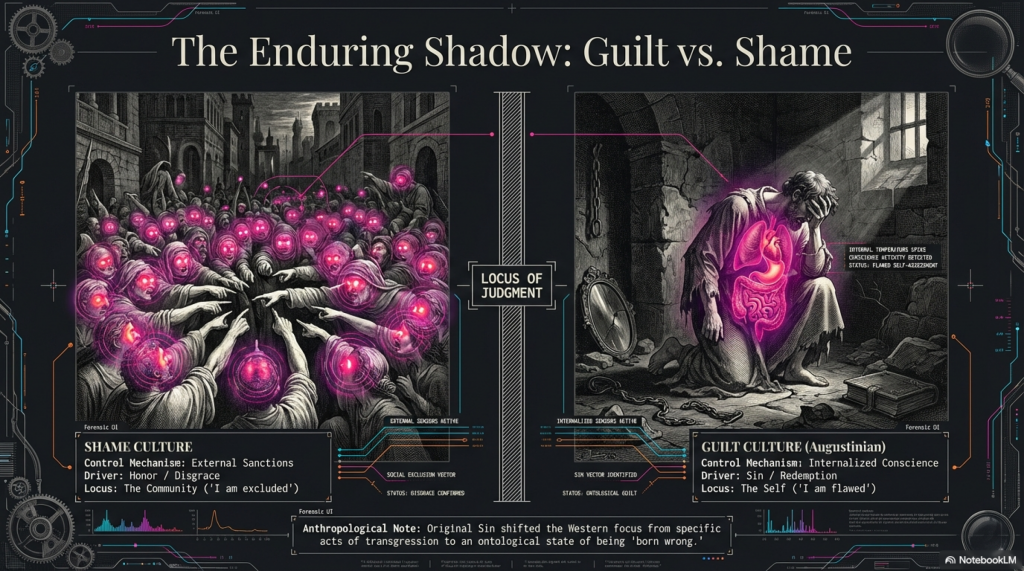

The Architecture of Guilt vs. Shame

Here, the analysis pivots to cultural anthropology. It distinguishes between “Shame Cultures”—driven by external social sanctions and community exclusion—and “Guilt Cultures,” which are powered by an internalized conscience. The commentary notes a critical historical shift: Original Sin moved the Western focus from specific acts of transgression to an “ontological state”. In this framework, the individual is not judged for what they do, but for what they are—an entity “born wrong”

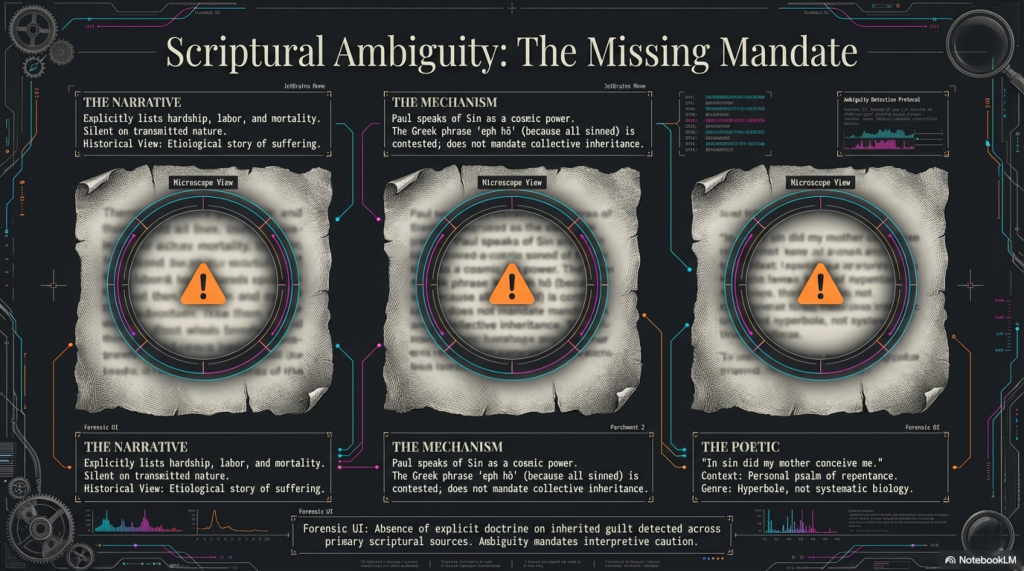

The Scriptural Ambiguity

This slide investigates the “Missing Mandate” within primary sources. The forensic UI highlights a significant gap: while Genesis 3 explicitly lists hardship and mortality, it remains silent on the idea of a transmitted nature. Even the poetic “In sin did my mother conceive me” is reframed here not as systematic biology, but as hyperbolic personal repentance. The verdict is one of “interpretive caution,” noting that the explicit doctrine of inherited guilt is absent from the very sources claimed to support it.

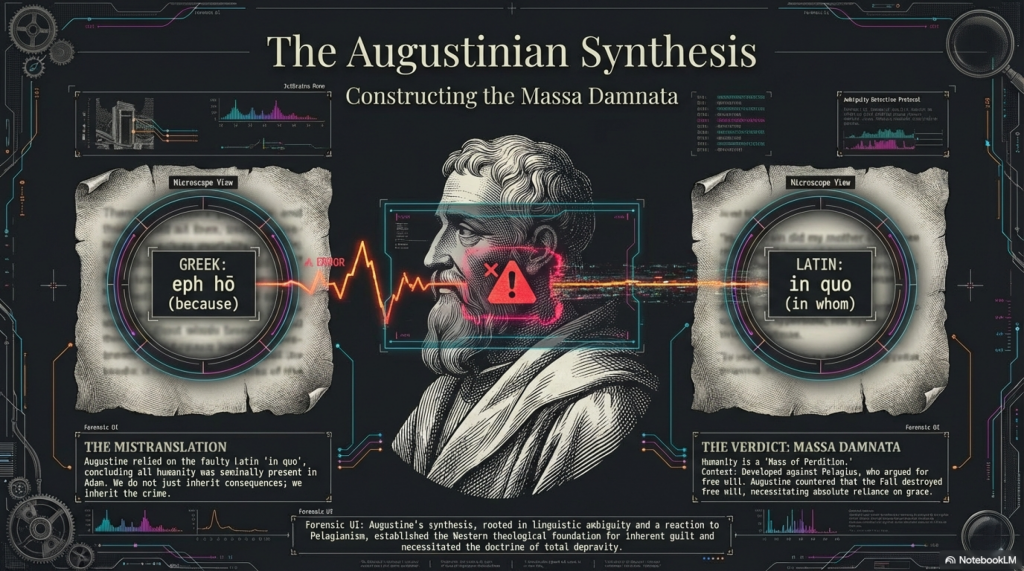

The Augustinian Synthesis

We arrive at the “smoking gun” of Western theology: a linguistic error. Augustine’s doctrine of the Massa Damnata (the Mass of Perdition) was built upon a faulty Latin translation. Where the original Greek eph hō meant “because all sinned,” the Latin in quo suggested we were all “in whom” (Adam) and therefore present at the crime. This transition ensured that humanity would not just inherit the consequences of the Fall, but the legal debt of the crime itself.

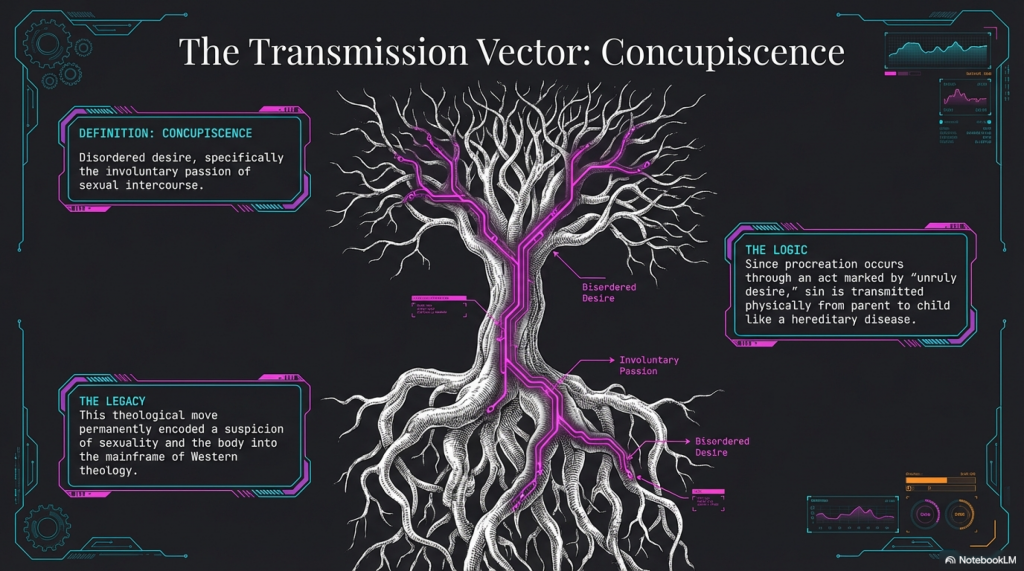

The Transmission Vector (Concupiscence)

How is this “sin” physically passed down? The presentation identifies “Concupiscence”—disordered, involuntary sexual desire—as the biological delivery system. By linking the act of procreation to “unruly desire,” Augustine physically encoded a deep-seated suspicion of sexuality and the body into the mainframe of Western thought. Sin is no longer just a choice; it is a “hereditary disease” transmitted through the very act that creates life.

The acrostic TULIP: total depravity, unconditional election, limited atonement, irresistible grace, and perseverance of the saints.

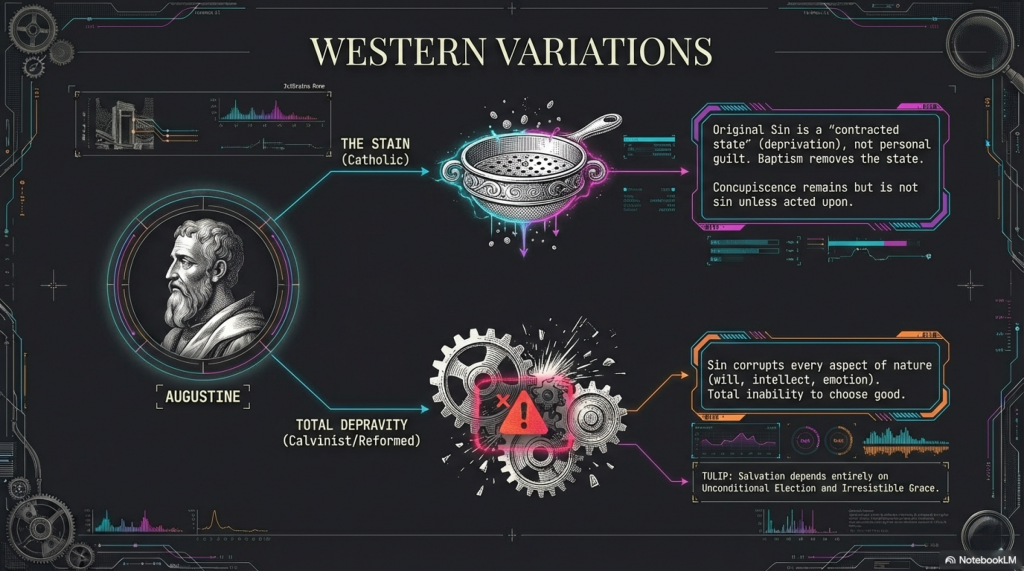

Western Variations: Catholic vs. Reformed

This slide maps the divergent paths of this doctrine in the West. The Catholic model views Original Sin as a “contracted state” or deprivation that can be removed by Baptism, though concupiscence remains. In contrast, the Calvinist/Reformed tradition advances “Total Depravity,” arguing that sin corrupts every aspect of human nature—will, intellect, and emotion—leaving the individual totally unable to choose good without irresistible grace.

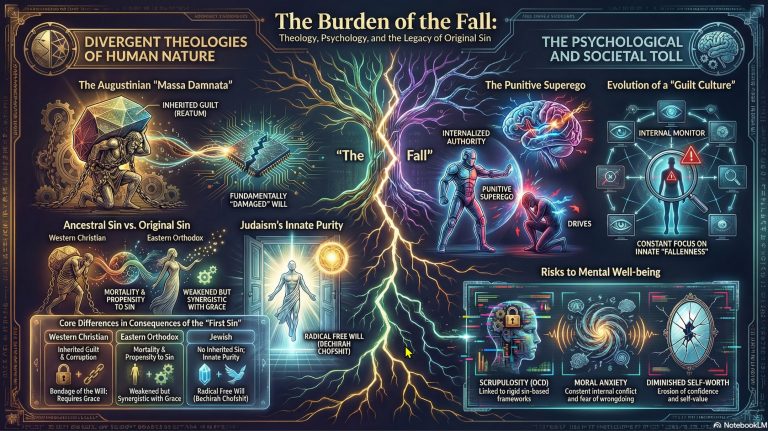

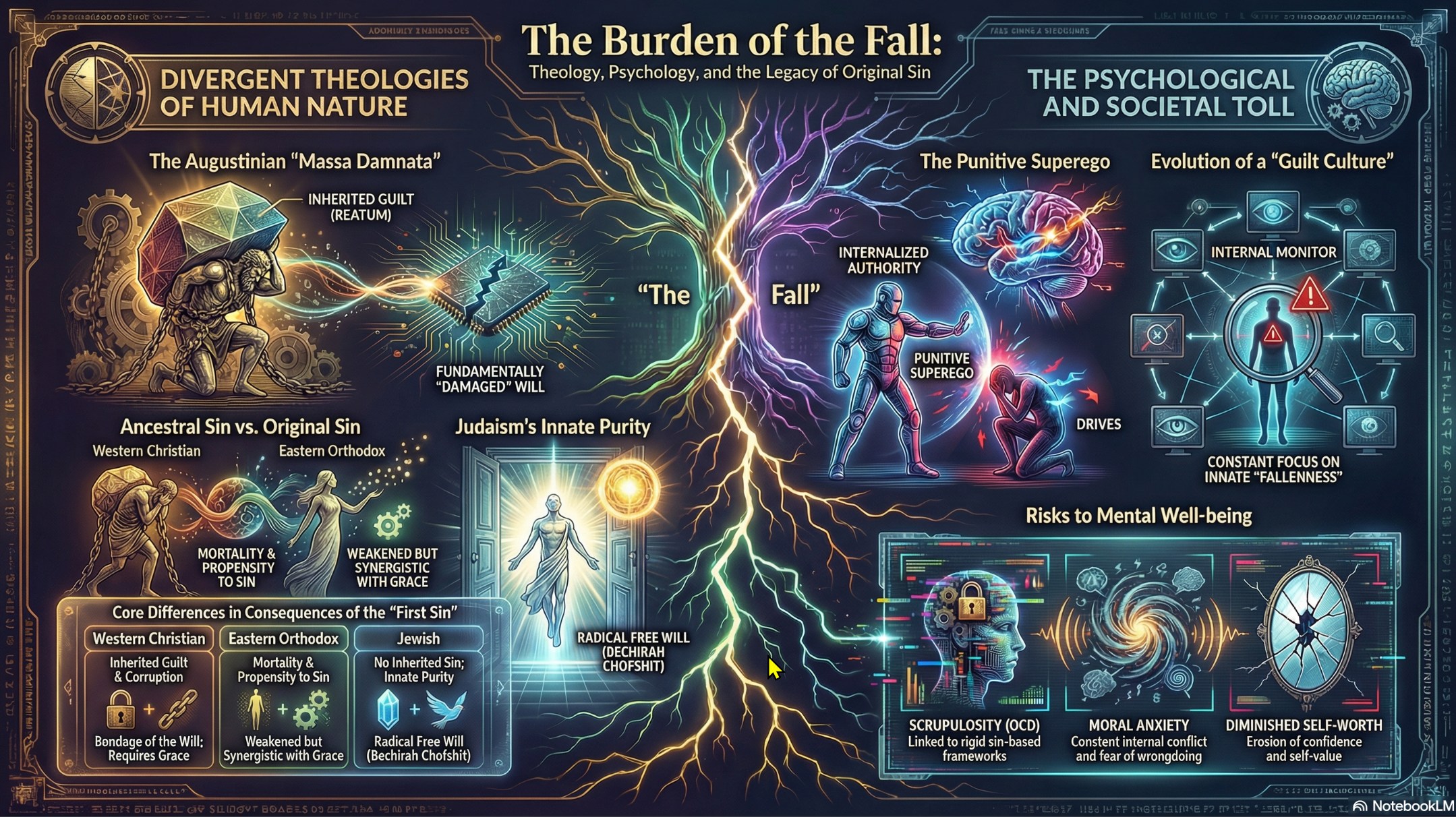

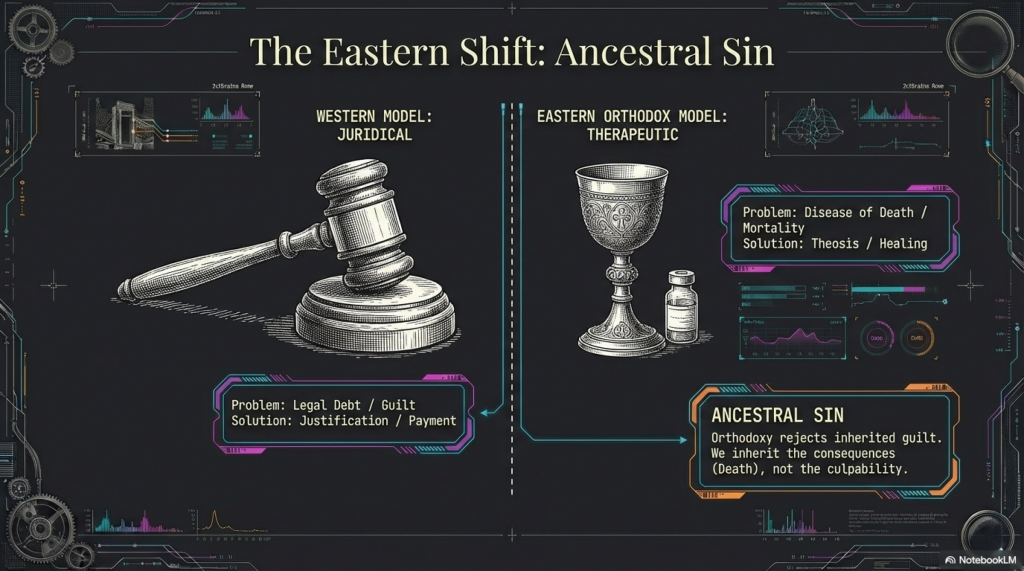

The Eastern Shift: Ancestral Sin

A sharp contrast is found in the Eastern Orthodox model, which is “Therapeutic” rather than “Juridical”. Rejecting inherited guilt, the East speaks of “Ancestral Sin”. In this view, we inherit the disease of death and mortality, but not the culpability of Adam. The goal is not the payment of a legal debt, but Theosis—the healing and divinization of the human person.

Addenda

We can analyze the fundamental divergence between the Western Juridical Model and the Eastern Therapeutic Model of sin. This distinction represents one of the most significant schisms in theological and psychological thought.

The Western Model: Juridical and Legalistic

In the Western tradition, largely shaped by Augustinian thought, the Fall is framed as a legal catastrophe.

- The Problem as “Debt”: Sin is viewed primarily as a “Legal Debt” or “Guilt” incurred against a divine legislator.

- The Mechanism of Inherited Culpability: Because of the “Massa Damnata” synthesis, humanity is seen as inheriting not just the environment of sin, but the actual crime and legal liability of Adam.

- The Solution as “Payment”: Consequently, the theological solution is “Justification” or “Payment”—a transaction to satisfy a legal requirement.

- Psychological Impact: This model often results in a “Guilt Culture” where the individual feels an ontological state of being “born wrong,” leading to chronic anxiety and an erosion of self-worth.

The Eastern Model: Therapeutic and Organic

The Eastern Orthodox tradition offers a “Therapeutic” shift, viewing the Fall more as a medical or biological tragedy than a legal one.

- The Problem as “Disease”: Instead of legal guilt, the primary problem is the “Disease of Death” or “Mortality”.

- Ancestral Sin vs. Original Sin: Orthodoxy explicitly rejects the idea of “inherited guilt”. While humans inherit the consequences of the Fall (death, suffering, and a fractured environment), they do not inherit the culpability or the personal “sin” of the ancestors.

- The Solution as “Healing”: The remedy is not a legal payment, but Theosis—the organic healing and restoration of the human person to a state of life.

- Psychological Impact: By decoupling “Self” from “Inherited Guilt,” this model shifts the focus from managing a “flawed nature” to pursuing a “healing potential”.

Comparison of Models

| Feature | Western Model (Juridical) | Eastern Model (Therapeutic) |

| Core View of Sin | Legal Debt / Guilt | Disease / Mortality |

| Inheritance | Culpability for the crime | Consequences of the act |

| Primary Goal | Justification / Payment | Healing / Theosis |

| Cultural Driver | Internalized Conscience / Guilt | Restoration of Life |

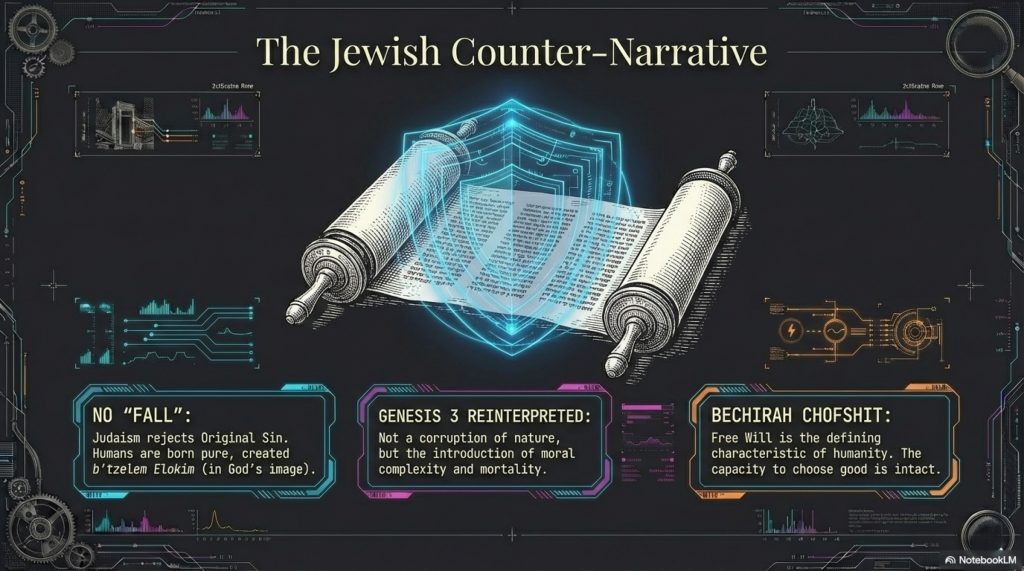

The Jewish Counter-Narrative

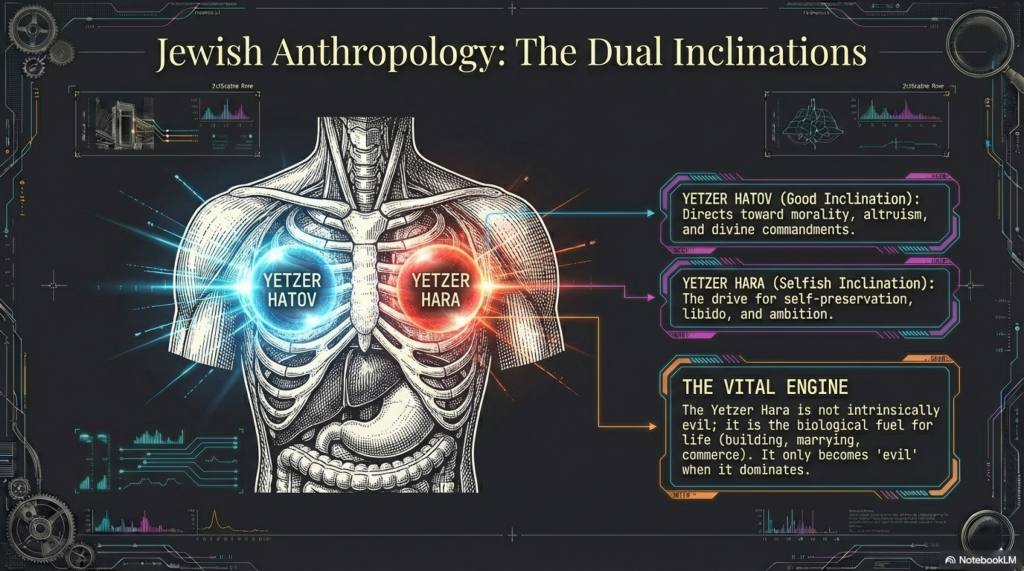

Returning to the roots of the narrative, Judaism offers a radical rejection of Original Sin. Humans are born pure, created b’tzelem Elokim (in God’s image). Genesis 3 is reinterpreted not as a corruption of nature, but as the arrival of moral complexity. This is managed through the dual inclinations: the Yetzer Hatov (moral drive) and the Yetzer Hara (selfish drive). Crucially, the Yetzer Hara is not evil; it is the “biological fuel” for life, becoming problematic only when it lacks balance.

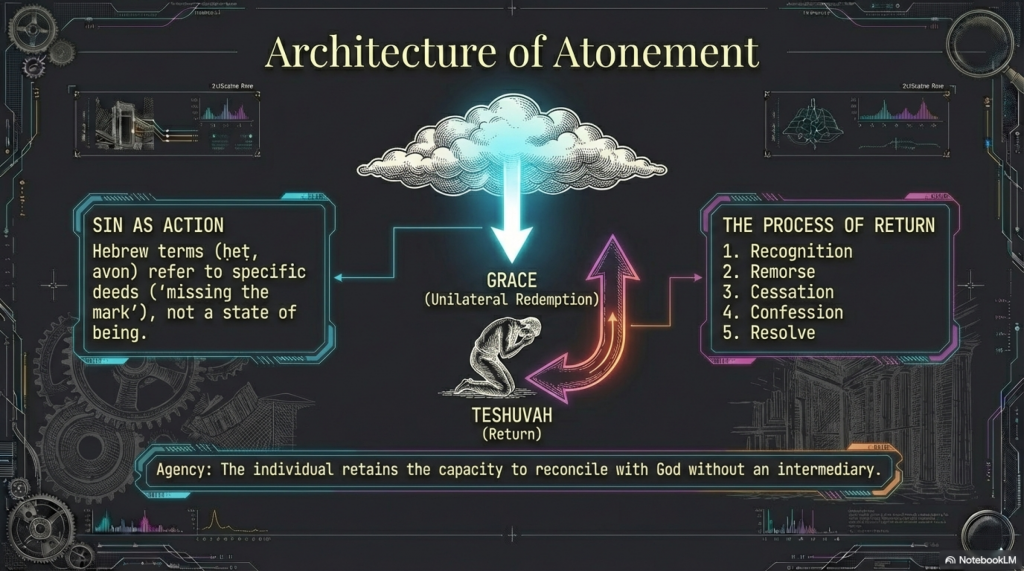

Architecture of Atonement

In the Jewish framework, sin is strictly an action—a “missing of the mark” (het)—not a state of being. This allows for the process of Teshuvah (Return), a five-step path of recognition, remorse, cessation, confession, and resolve. Human agency remains intact; the individual can reconcile with the Divine directly without the need for an intermediary to “fix” a broken nature.

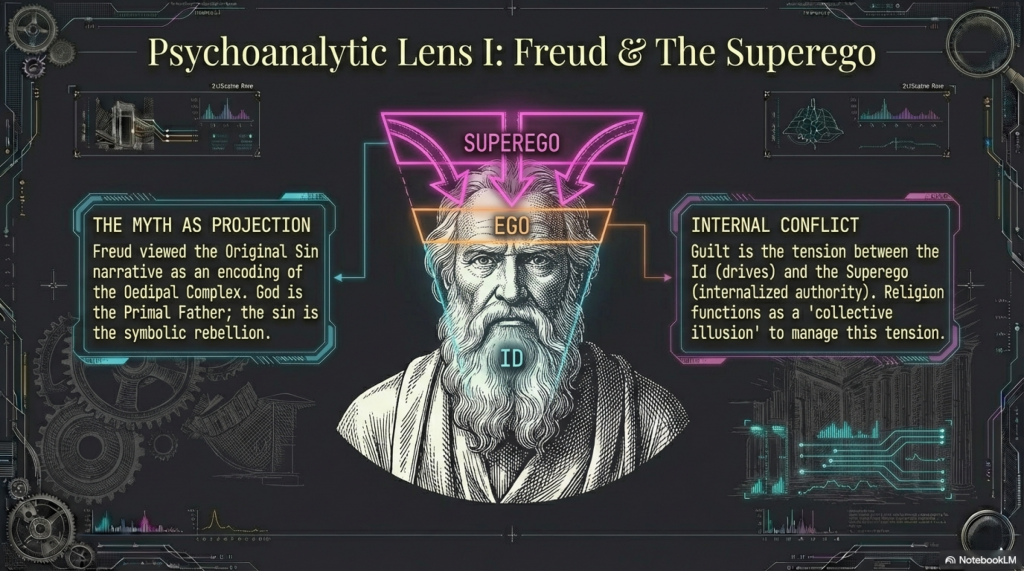

Freud and the Superego

The investigation moves into the psychoanalytic era. Freud views the Original Sin narrative as a symbolic encoding of the Oedipal Complex, where “God” is the Primal Father and sin is the rebellion against his authority. Guilt is defined here as the internal “tension” between the biological drives of the Id and the internalized authority of the Superego. Religion, in this lens, is a “collective illusion” designed to manage this inherent psychic friction.

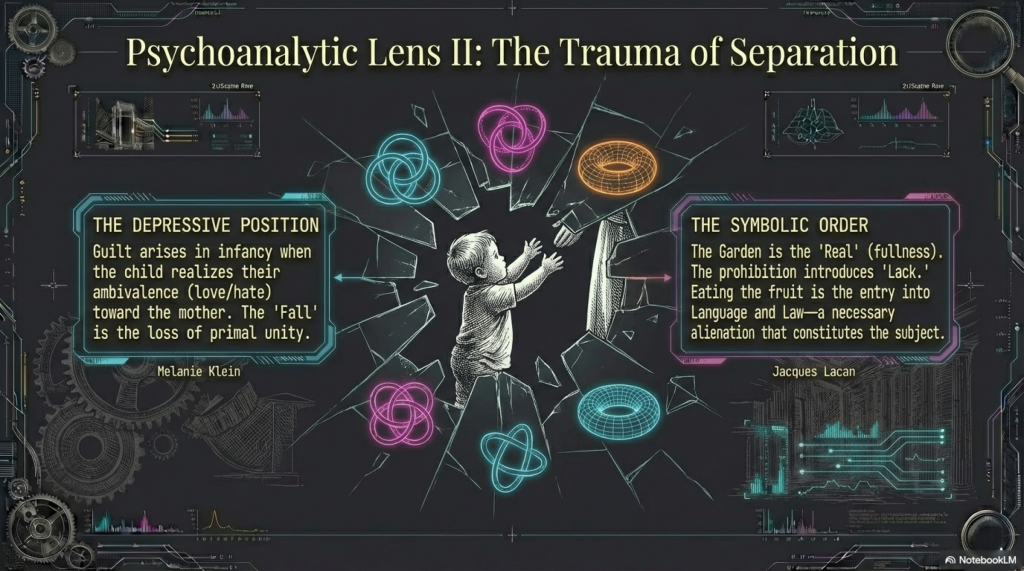

The Trauma of Separation

Building on Freud, Melanie Klein and Jacques Lacan offer deeper insights. Klein sees the “Fall” as the loss of primal unity with the mother, where guilt emerges from the infant’s realization of their own “ambivalence” (love/hate). Lacan reframes the Garden as the “Real” (fullness), where eating the fruit represents the entry into “Language and Law”—a necessary alienation that creates the “subject” through the introduction of “Lack”.

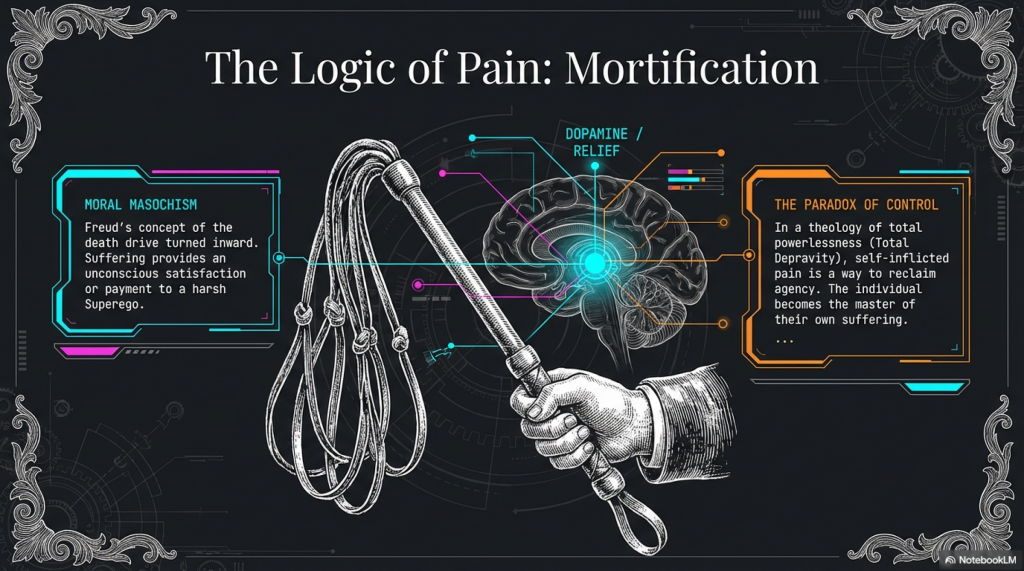

The Logic of Pain

This slide examines the “Paradox of Control” found in practices of mortification. In a theology of “Total Depravity” where one is powerless, self-inflicted pain becomes a way to reclaim agency. The individual becomes the “master of their own suffering”. Freud’s concept of “Moral Masochism” suggests that this suffering provides a twisted “unconscious satisfaction” or payment to a harsh, internalized Superego.

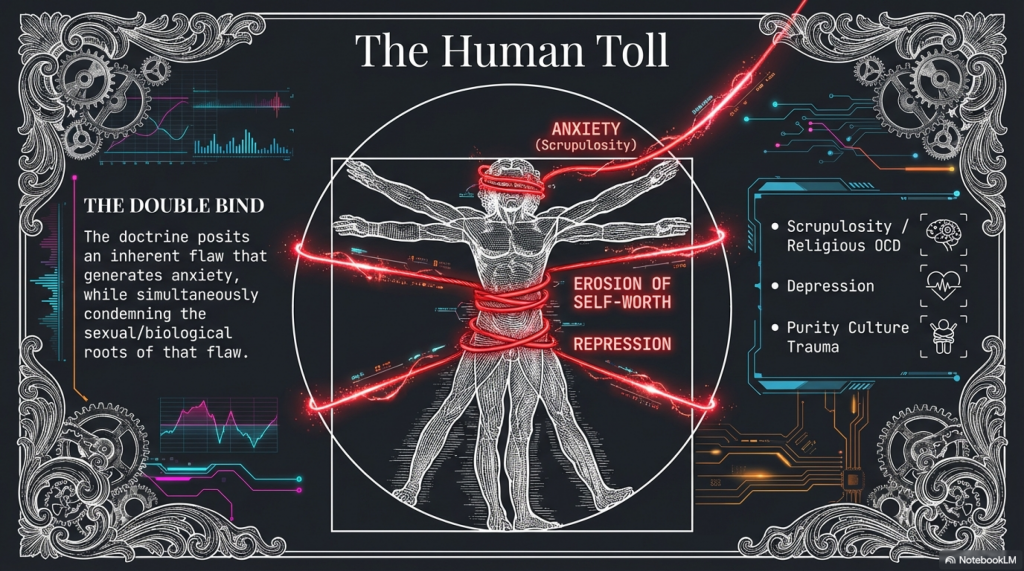

The Human Toll

The clinical results of this doctrine are laid bare: the “Erosion of Self-Worth”. The doctrine creates a “Double Bind,” where an inherent flaw generates anxiety while the very biological roots of that flaw are condemned. This manifests as Scrupulosity (Religious OCD), depression, and the lasting trauma associated with “Purity Culture”.

Conclusion: The Burdened Legacy

We conclude with a final paradox. For Augustine, this doctrine was the only way to ensure the absolute necessity of Grace. However, the price paid was a “Western consciousness rooted in defect rather than potential”. The final verdict suggests that by viewing Original Sin as a “constructed myth” rather than “divine fact,” we can begin to decouple “Guilt” from the “Self”—a vital step toward achieving true psychological integrity.

A Long Audio Presentation

Original Sin, Guilt, and the Psyche: A Theological, Comparative, and Psychoanalytic Inquiry

Abstract

This article presents an interdisciplinary analysis of the Christian doctrine of Original Sin, tracing its profound influence on Western thought from theological, comparative, and psychoanalytic perspectives. The inquiry begins by deconstructing the doctrine’s origins, demonstrating that it is less a direct scriptural mandate than a theological architecture constructed by Augustine of Hippo from ambiguous biblical texts. This Western Christian framework, centered on inherited guilt and a fallen human nature, is then placed in stark contrast with the Jewish counter-narrative, which emphasizes innate purity, free will, and personal responsibility for one’s actions. The analysis subsequently employs the hermeneutic tools of psychoanalysis—drawing from Freudian, Kleinian, and Lacanian theory—to reinterpret the Adamic myth and its associated concepts of guilt and penance as potent expressions of unconscious psychic dynamics related to authority, desire, and loss. Finally, the article evaluates the doctrine’s tangible societal and psychological legacy, arguing that it was a key factor in fostering a “guilt culture” in the West and that its internalization can contribute to diminished self-worth, moral anxiety, and specific mental health challenges. The central thesis concludes that the doctrine of Original Sin represents a profound paradox: a concept theologically indispensable to certain Christian frameworks, yet one that has exacted a considerable and demonstrable toll on the psychic and cultural life of the West.

1.0 Introduction: The Enduring Shadow of Original Sin

The doctrine of Original Sin stands as a foundational yet deeply contested concept within Western Christian theology. Its core tenet posits a fundamental flaw in human nature—an inherited condition of sinfulness and guilt stemming from the primordial disobedience of Adam and Eve—which strategically orients the entire theological problematic of humanity, grace, and the necessity of salvation through Christ. This framework, however, finds no direct parallel in Judaism, which offers a contrasting view of innate human purity and free will, immediately highlighting the particularity of the Christian doctrine and its profound implications.

The influence of Original Sin extends far beyond theological discourse, exerting a pervasive, often unexamined, influence on Western culture. Its doctrinal logic, which internalizes fault as an ontological state rather than a mere action, became a primary engine for shaping Western conceptions of guilt, ethics, and sexuality. Anthropologists have argued that its emphasis on innate corruption was a key factor in the development of a “guilt culture”—one governed by an internalized conscience rather than external shame. Its historical association with sexual desire as the mechanism of transmission has also fostered a complex and often troubled relationship with the body within many Christian traditions.

This article undertakes a scholarly, interdisciplinary analysis of the doctrine, examining it through the lenses of theology, history, comparative religion, and psychoanalysis. It will scrutinize the doctrine’s scriptural basis and historical development, with a focus on the pivotal role of Augustine of Hippo. This Western Christian framework will then be contrasted with the distinct Jewish understanding of sin and human inclination. Finally, it will employ Freudian, Kleinian, and Lacanian theories to interpret the psychological dynamics of guilt and penance.

The central tension of the doctrine lies in its perceived theological necessity versus the significant ethical, scriptural, and psychological critiques leveled against it. For its proponents, Original Sin is indispensable for explaining the human predicament and the absolute need for Christ’s redemptive work. For its critics, it raises troubling questions about divine justice, free will, and its potential to foster excessive anxiety and a negative view of the self. This inherent conflict necessitates the multi-layered, interdisciplinary examination that follows, aiming to assess the societal and psychological burdens imposed by a framework centered on the concept of innate guilt.

2.0 The Genesis and Augustinian Architecture of Original Sin

The doctrine of Original Sin, as it is understood in the Western Christian tradition, is not a direct transcription of biblical text but a theological construct developed over several centuries. While built upon interpretations of key scriptural passages, it was Augustine of Hippo who synthesized these elements into the coherent and influential doctrine that would shape Western thought. This section deconstructs its origins by examining its ambiguous scriptural roots and the pivotal historical context of Augustine’s synthesis.

2.1 Scriptural Roots and Pre-Augustinian Interpretations

The doctrine traditionally draws support from three primary biblical texts. However, critical analysis reveals significant ambiguity in these passages, suggesting that the later doctrine represents a specific interpretive choice rather than a direct scriptural mandate.

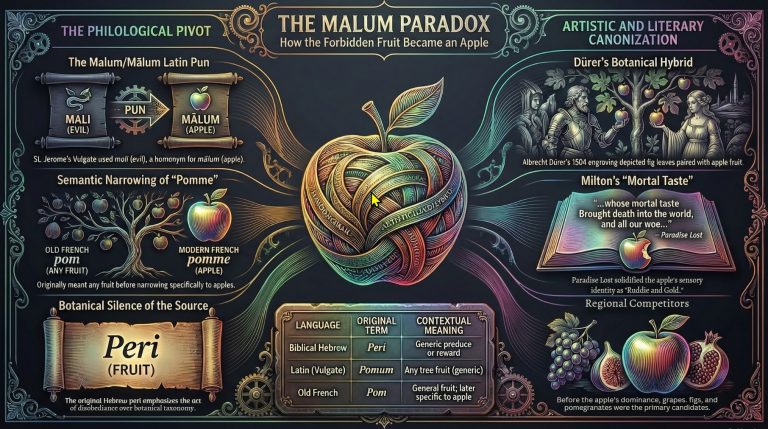

• Genesis 3: Traditionally interpreted as “the Fall” of humanity into sin, the text itself is silent on the concept of inherited guilt or an innately corrupted human nature. The explicit consequences listed are hardship, pain in childbirth, enmity, and physical mortality—not a transmitted sinful state. Historical-critical scholarship suggests the story may primarily serve an etiological function, explaining the origins of human hardship and suffering.

• Romans 5:12: Arguably the most crucial text for the doctrine, Paul writes, “…sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned…” Scholars often interpret Paul’s concept of “Sin” here not as individual transgressions but as a personified “cosmic power” that enslaves humanity. The final Greek clause, eph hō pantes hēmarton (“because all sinned”), is notoriously contested and does not necessitate the later interpretation that all humanity sinned in Adam.

• Psalm 51:5: The verse, “Behold, I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin did my mother conceive me,” is often cited as proof of innate sinfulness. However, situated within a personal psalm of repentance, it can be read as a hyperbolic expression of the psalmist’s profound sense of personal unworthiness rather than a formal theological statement on the ontological state of all humans at birth.

Reflecting this scriptural ambiguity, pre-Augustinian Christian thought, while acknowledging universal sinfulness, lacked the specific formulation of a biologically transmitted guilt that Augustine would later develop.

2.2 Augustine’s Synthesis: Inherited Guilt and Concupiscence

Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) became the primary architect of the Western doctrine and was the first known author to use the Latin phrase peccatum originale (“original sin”). His powerful synthesis consisted of two core components, shaped decisively by his polemical debate with the monk Pelagius.

1. Inherited Guilt (reatum): Augustine’s argument for inherited guilt was founded on a faulty Latin translation of Romans 5:12. The phrase eph hō was rendered as in quo (“in whom”), leading him to argue that all of humanity was “seminally present in Adam” and therefore participated directly in his sin. This interpretation meant that Adam’s transgression was a collective act, rendering all subsequent generations a massa damnata—a “mass of perdition” inherently deserving of condemnation from birth.

2. Concupiscence as Mechanism: Augustine identified concupiscence—disordered desire, specifically the involuntary passion of sexual intercourse—as the biological vehicle for transmitting this sin. Because procreation occurs through this act, which is marked by unruly desire, he argued that the sin itself is passed down from parent to child like a hereditary disease. This linkage deeply ingrained a suspicion of sexuality within Western Christianity.

This framework was sharpened in Augustine’s fierce theological battle with Pelagius, who taught that humans are born morally neutral with the free will to choose good or evil. Augustine saw this teaching as a grave threat, undermining the necessity of Christ’s redemption. In opposition, he argued that the Fall had so damaged free will that humanity was incapable of choosing good without God’s prevenient grace. This victory solidified the absolute necessity of grace and the essential role of the Church’s sacraments, particularly infant baptism, to wash away the stain of original sin. Augustine’s synthesis was thus not merely a historical development; it was the architectural moment where specific psychological burdens—a consciousness of inherent guilt and a foundational suspicion of sexuality—were permanently encoded into the mainstream of Western theology.

2.3 Doctrinal Solidification and Variations

Augustine’s views were largely affirmed in the Western Church at the Councils of Carthage (418 CE) and Orange (529 CE), solidifying his doctrine as official teaching. From this common Augustinian root, however, significant variations evolved across different Christian traditions.

| Tradition | Key Interpretation of Original/Ancestral Sin |

|---|---|

| Roman Catholicism | Views original sin as a “contracted state” of deprivation of holiness, not personal guilt (culpa). Baptism is believed to erase this state, though the inclination to sin (concupiscence) remains. This framework necessitates the Immaculate Conception, whereby Mary was preserved from this state. |

| Eastern Orthodoxy | Rejects inherited guilt entirely, speaking instead of “Ancestral Sin.” Humanity inherits the consequences—mortality and corruption—but not Adam’s personal guilt. Salvation is a therapeutic process of theosis (deification) to heal human nature from the disease of death. |

| Protestantism (General) | Whereas Catholicism sought to moderate the Augustinian legacy, major Protestant traditions largely intensified his core premises through the doctrine of “Total Depravity,” which holds that sin has corrupted every aspect of human nature, rendering individuals unable to save themselves. |

| Calvinism | Defines “Total Depravity” as a total inability to choose good. Salvation is based on God’s sovereign choice through “irresistible grace.” |

| Arminianism/Methodism | Affirms “Total Depravity” but holds that God provides “prevenient grace” to all, enabling a free response to the offer of salvation. |

| Lutheranism | Holds a hybrid position, affirming “Total Depravity” and salvation by grace alone while rejecting the Calvinist doctrine of double predestination. |

This stark dichotomy between a juridical problem of guilt and a therapeutic problem of mortality sets the stage for a tradition that rejects both frameworks entirely.

3.0 A Counter-Narrative: Judaism on Sin, Inclination, and Responsibility

The Jewish perspective provides a fundamental counter-narrative to the Christian doctrine of Original Sin. It offers an alternative anthropological framework centered on innate purity, personal agency, and direct moral responsibility for one’s actions.

3.1 Rejection of Original Sin and Affirmation of Free Will

Judaism unequivocally rejects the concept of Original Sin. The tradition teaches that humans are born pure and sinless, created in the image of God. There is no inherited guilt or innate corruption transmitted from Adam and Eve. The Genesis 3 narrative is understood to have introduced mortality and struggle into the human experience, but it did not corrupt human nature itself. Central to Jewish anthropology is the principle of bechirah chofshit (free will), which endows humans with the capacity to choose between right and wrong, making them morally responsible agents.

3.2 The Dynamics of Inclination: Yetzer Hatov and Yetzer Hara

Instead of a single, fallen nature, Jewish thought posits that every person possesses two innate drives: the Yetzer Hatov (the good inclination) and the Yetzer Hara (the evil inclination). The Yetzer Hatov guides a person toward morality, while the Yetzer Hara represents the drives for self-interest, physical desire, and immediate gratification.

Critically, the Yetzer Hara is not considered intrinsically demonic. Rabbinic thought views it as a necessary engine for life, driving ambition, procreation, and commerce; it only becomes problematic when it dominates the individual. The human condition is thus a continuous internal struggle. Some traditions suggest the Yetzer Hara is present from birth while the Yetzer Hatov develops later with moral maturity, initially placing the good inclination at a disadvantage.

3.3 Sin as Action and the Path of Teshuvah

In line with its emphasis on responsibility, Judaism defines sin primarily as an action—a violation of a divine commandment—not as an inherited state. Hebrew terms for sin, such as ḥeṭ (an unintentional miss), avon (a moral failing), and pesha (a rebellious act), all point to specific deeds. The cornerstone of Jewish atonement is the concept of Teshuvah (“return”), a multi-step process that underscores the individual’s active role in achieving reconciliation with God. This process involves:

1. Recognition of wrongdoing

2. Sincere remorse

3. Cessation of the act

4. Confession to God

5. A firm resolve not to repeat the sin

This model of self-initiated reconciliation stands in stark contrast to the Augustinian model of external redemption from an inherited debt, thereby setting the stage for a psychological examination of the latter.

4.0 Psychoanalytic Readings of Guilt, Faith, and Mortification

Psychoanalysis provides a non-theological, secular hermeneutic for interpreting religious doctrines. It reframes concepts like guilt, sin, and penance as expressions of unconscious psychic dynamics, offering a deeper understanding of their powerful appeal by exploring the internal conflicts of the human mind.

4.1 The Psyche’s Burden: Guilt, the Superego, and Religion

Psychoanalytic theory views guilt as an internal conflict rather than simply a response to breaking an external rule. Key theorists offer distinct perspectives on its origin and function.

• Freud: Guilt arises from the tension between the Id’s forbidden desires and the condemnations of the Superego, which is formed from internalized parental and societal authority. Freud viewed religion as a “collective illusion” for managing infantile helplessness, with God serving as an exalted, projected father figure.

• Klein: Melanie Klein located the origins of guilt in the “depressive position” of early infancy, where the child first feels remorse over its own fantasized sadistic attacks on the mother as a whole person, sparking a desire for reparation.

• Lacan: Jacques Lacan offered a structural view, suggesting guilt can function as a defense mechanism or as a structural element of subjectivity that arises from the individual’s entry into the Symbolic order—the realm of language, law, and social structures.

4.2 Interpreting the Original Sin Narrative

Psychoanalysis treats the Original Sin story as a myth that encodes psychological realities, not as literal history. Different theoretical lenses reveal distinct layers of meaning.

• Freudian Lens: The narrative maps onto the Oedipal drama. God is the primal father whose prohibition is transgressed, and the “sin” is a symbolic rebellion against his authority, leading to an inherited, collective guilt.

• Kleinian/Object Relations Lens: The Garden of Eden can be interpreted as a symbol of primal unity with the mother. The expulsion represents the trauma of separation and object loss, while the “knowledge of good and evil” signifies the infant’s entry into the depressive position and the painful awareness of ambivalence toward the loved object.

• Lacanian Lens: The Garden represents the pre-Symbolic Real, a state of imaginary fullness. God’s prohibition is the Law of the Father that introduces “lack,” and the forbidden fruit symbolizes the objet petit a (the unattainable object-cause of desire). Eating the fruit signifies the subject’s alienating entry into the Symbolic order.

• Ricoeur’s Symbolic Approach: Philosopher Paul Ricoeur analyzed the Adamic myth through a hermeneutic lens, seeing it as a primary symbol that portrays evil as a contingent misuse of freedom. It expresses the experience of a “servile will,” a rupture between human potential and our actual fallen existence, thereby “giving rise to thought” about fault and responsibility.

4.3 The Logic of Expiation: Corporal Mortification

Practices of corporal mortification, such as self-flagellation, are consciously motivated by a desire for penance and to imitate Christ’s suffering. Psychoanalysis elucidates the unconscious dynamics behind such acts.

• Guilt and Self-Punishment: These practices can be a concrete enactment of the “need for punishment” demanded by a harsh Superego to atone for real or imagined transgressions.

• Moral Masochism: This concept describes a paradoxical satisfaction derived from suffering, linked to the death drive turned inward. Extreme asceticism can represent this dynamic.

• Control and Agency: Paradoxically, self-inflicted pain can be an attempt to assert agency and gain a measure of control in a world of perceived powerlessness.

Psychoanalysis thus reinterprets these religious phenomena as powerful internal psychic dramas, attempts to manage the profound and often painful conflicts that define the human mind.

5.0 The Societal and Psychological Toll

The Augustinian formulation of Original Sin has exerted a tangible and often burdensome influence beyond the individual. It has left a distinct legacy in shaping collective cultural norms and has had a specific impact on the individual psyche.

5.1 Fostering a Culture of Guilt

Anthropologists distinguish between “guilt cultures,” which rely on an internalized conscience for moral control, and “shame cultures,” which rely on external sanctions like public honor and disgrace. A strong scholarly argument posits that the doctrine of Original Sin was a crucial engine in developing the West into a predominantly guilt culture. By defining sin not merely as an act but as an inherent state, the doctrine internalizes the locus of moral judgment. The problem lies within the self, fostering an intense, self-monitoring conscience—or a powerful Superego—perpetually preoccupied with innate fallenness. This internal monitor has influenced Western ethics and has underpinned political philosophies skeptical of human perfectibility.

5.2 The Burden on the Individual Psyche

For individuals who internalize a belief in Original Sin, the psychological consequences can be significant and detrimental.

• Self-Worth and Anxiety: The idea of being born inherently flawed or guilty can profoundly undermine self-worth, fostering a baseline feeling of inadequacy. This often translates into heightened moral anxiety—the fear of transgressing internalized standards and incurring punishment, whether from God or from one’s own conscience.

• Repression and Sexuality: Augustine’s identification of concupiscence as the vehicle for transmitting sin has contributed to a historical suspicion of sexuality, associating it with humanity’s fallen nature. This can lead to the repression of natural sexual feelings, generating guilt and shame that psychoanalysis links to neurosis. Modern phenomena like “purity culture” movements exemplify the potential harms of this theological legacy.

• Mental Health Challenges: Rigid religious interpretations emphasizing guilt can contribute to or exacerbate mental health conditions. Research has linked such beliefs to anxiety disorders, depression, and scrupulosity (a form of OCD characterized by religious obsessions). In severe cases, such negative religious experiences can constitute a clinically relevant form of religious trauma.

The doctrine can create a psychological “double bind”: it posits an inherent flaw that generates anxiety, while the very defenses used to manage it, such as repression, can themselves be detrimental to mental health. This psychological double bind—where an innate flaw provokes inherently flawed defenses—reveals the profound and often circular burden the doctrine can place upon the individual psyche.

6.0 Conclusion: Synthesizing Perspectives on a Burdened Legacy

This inquiry has navigated the doctrine of Original Sin as a theological construct, demonstrating its foundation in Augustine of Hippo’s interpretation of ambiguous scriptures within a polemical context. From this Augustinian root, major Christian traditions diverged significantly: Catholicism nuanced the doctrine as a “contracted state,” Eastern Orthodoxy rejected inherited guilt entirely in favor of “Ancestral Sin,” and Protestantism fractured over the implications of “Total Depravity.” In stark opposition, the Jewish counter-narrative offers a model of innate purity, free will, and self-initiated reconciliation through Teshuvah. Psychoanalytic perspectives, in turn, reframe the doctrine and its associated practices as potent myths encoding deep psychological conflicts over authority, desire, and guilt.

Synthesizing these viewpoints reveals the doctrine’s significant societal and psychological toll. Its framework of inherent flawedness was a key factor in shaping a Western “guilt culture” and carries the potential to negatively impact individual self-worth, foster anxiety, and contribute to mental health challenges.

The legacy of Original Sin is therefore one of profound paradox—a doctrine of radical dependence that proved theologically indispensable to certain Christian architectures, yet one that has exacted a considerable and demonstrable toll on the psychic and cultural life of the West. Acknowledging this burdened inheritance is not an act of dismissal, but a necessary step in the ongoing critical engagement required for both theological integrity and the pursuit of psychological well-being.