- Introduction

- Nicholas of Cusa’s Jewish Influences

- Maimonides and Rabbi Solomon

- Meister Eckhart’s Mediation

- Christian Neoplatonism Roots

- Christian Neoplatonism and Jewish Philosophy

- The Search for ‘Dux Neutrorum’

- Impact on Renaissance Thought

- Mystical Theology in Cusanus

- Philosophical Synthesis in Theology

Nicholas of Cusa: Influences and Origins

Curated by rachav_foundation

Nicholas of Cusa, a 15th-century German theologian and philosopher, engaged with Jewish thought primarily through texts rather than direct contact with rabbis. His work shows influence from Maimonides, particularly in his concept of “learned ignorance,” though this engagement was often mediated through earlier Christian thinkers like Meister Eckhart.

Nicholas of Cusa’s Jewish Influences

Nicholas of Cusa’s engagement with Jewish thought, while primarily indirect, was nonetheless significant in shaping his philosophical and theological ideas. Beyond his encounters with Maimonides’ work through Christian intermediaries, Cusanus demonstrated a broader interest in Jewish wisdom and mystical traditions.

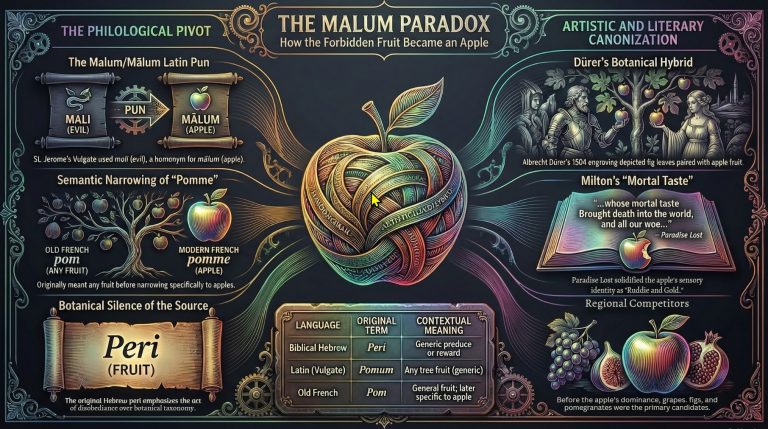

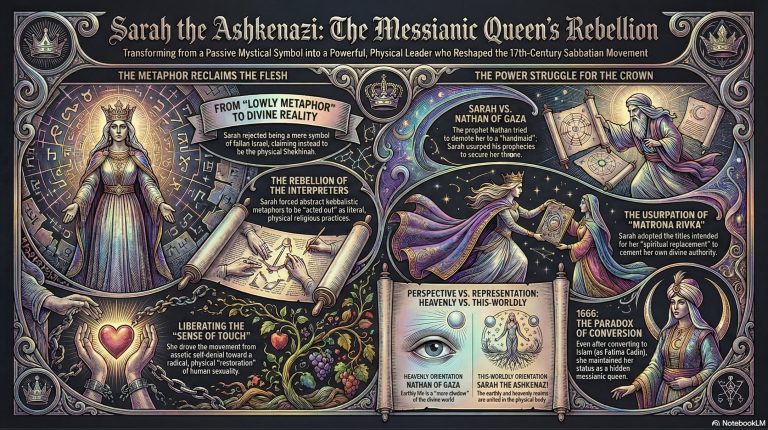

One notable influence was the Kabbalistic tradition, which Cusanus likely encountered through Christian interpretations and translations. His concept of the “coincidence of opposites” (coincidentia oppositorum) bears similarities to Kabbalistic notions of divine unity transcending apparent contradictions 1. This idea, central to Cusanus’ thought, may have been partially inspired by Jewish mystical concepts of God’s simultaneous immanence and transcendence.

Cusanus also engaged with Jewish philosophical ideas in his efforts to promote interfaith dialogue and understanding. In his work “De pace fidei” (On the Peace of Faith), written in response to the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Cusanus imagined a celestial council where representatives of various faiths, including Judaism, sought common ground 2. This work reflects his belief that different religious traditions could be reconciled through a deeper understanding of their shared spiritual truths.

Furthermore, Cusanus’ interest in Hebrew language and exegesis is evident in his writings. He occasionally referred to Hebrew terms and concepts, demonstrating at least a basic familiarity with Jewish scriptural interpretation. This engagement with Hebrew scholarship, albeit limited, was part of the broader Renaissance interest in returning to original sources and languages.

While Cusanus did not have direct contact with contemporary Jewish rabbis, his intellectual curiosity led him to seek out Jewish texts. Around 1450, he actively searched for a complete copy of Maimonides’ “Guide of the Perplexed” (Dux neutrorum), eventually locating one in a Dutch monastery and ordering a copy for the pope2. This effort underscores his genuine interest in Jewish philosophical thought and his recognition of its value for Christian theology.

Cusanus’ engagement with Jewish ideas, though filtered through Christian lenses, contributed to his unique intellectual synthesis. His openness to diverse philosophical and religious traditions, including elements of Jewish thought, helped shape his innovative approaches to theology, metaphysics, and interfaith understanding.

2 sources

Maimonides and Rabbi Solomon

Nicholas of Cusa’s engagement with Jewish thought, particularly that of Maimonides, was more complex and direct than previously understood. In his seminal work “De docta ignorantia” (1440), Cusanus explicitly cites passages from Maimonides’ “Guide of the Perplexed,” presenting them as authoritative statements on approaching the understanding of the Divine Being1. Interestingly, Cusanus attributes these quotations to a “Rabbi Solomon” rather than directly to Maimonides1.

This attribution to “Rabbi Solomon” may have been a deliberate choice by Cusanus. At the time of writing “De docta ignorantia,” he might have been hesitant to reveal his connection to the controversial 14th-century Dominican, Meister Eckhart, who had previously cited these same passages1. By using the pseudonym “Rabbi Solomon,” Cusanus could engage with Maimonides’ ideas while potentially avoiding association with Eckhart’s teachings, which had faced ecclesiastical censure.

Cusanus’s interest in Maimonides’ work was not fleeting. Around 1450, he actively sought a complete text of the “Dux neutrorum” (Latin translation of the “Guide of the Perplexed”)1. Upon locating a copy in a Dutch monastery, Cusanus went so far as to order a transcription for the pope, demonstrating the high regard in which he held Maimonides’ philosophical contributions 1.

This direct engagement with Maimonides’ text represents a significant departure from merely inheriting Jewish ideas through Christian intermediaries. It shows Cusanus as an active seeker of Jewish wisdom, willing to engage directly with primary sources. His approach to Maimonides’ work reflects the Renaissance humanist emphasis on returning to original texts and languages, even when those texts originated outside the Christian tradition.

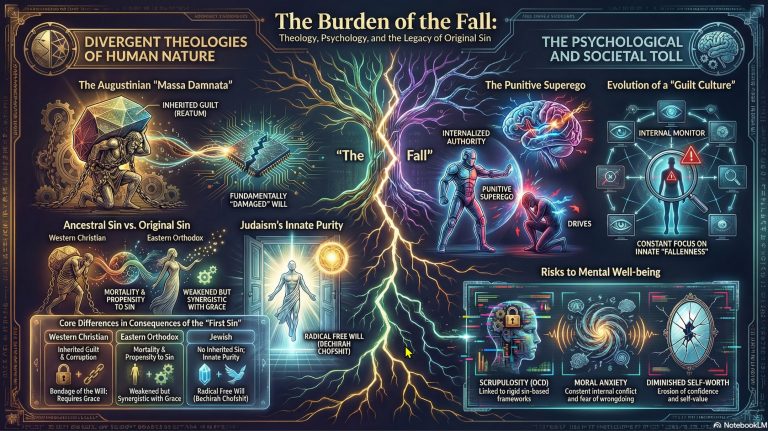

Cusanus’s use of Maimonides’ ideas, particularly in relation to negative theology and the limits of human knowledge in comprehending the divine, became foundational to his own doctrine of “learned ignorance.” This concept, central to Cusanus’s philosophy, owes a clear debt to Maimonides’ approach to divine incomprehensibility, demonstrating the profound impact of Jewish thought on one of the most influential Christian thinkers of the 15th century.

1 source

Meister Eckhart’s Mediation

Nicholas of Cusa’s engagement with Jewish thought, particularly that of Maimonides, was significantly mediated through the works of Meister Eckhart, the influential German Dominican theologian and mystic. This intellectual lineage played a crucial role in shaping Cusanus’s philosophical and theological ideas.

Meister Eckhart, who lived about a century before Cusanus, had extensively studied and incorporated Maimonides’ ideas into his own writings. Eckhart’s Exodus commentary, in particular, contained numerous quotations and summaries from Maimonides’ “Guide of the Perplexed”1. These passages, which Eckhart had carefully selected and interpreted, provided a Christian lens through which Maimonidean thought was transmitted to later thinkers like Cusanus.

Cusanus’s familiarity with Eckhart’s works is well-documented. During his time in Cologne, Cusanus was introduced to Eckhart’s writings, along with those of other influential thinkers1. This exposure was pivotal in shaping Cusanus’s intellectual development, as it provided him with a Christian framework for understanding and incorporating Jewish philosophical concepts.

The influence of Eckhart’s mediation is particularly evident in Cusanus’s approach to negative theology and the concept of learned ignorance. Eckhart had already adapted Maimonides’ ideas on the incomprehensibility of God to fit within a Christian mystical framework. Cusanus, in turn, further developed these concepts, leading to his doctrine of docta ignorantia2.

Interestingly, while Cusanus borrowed heavily from Eckhart’s interpretations of Maimonides, he was cautious about explicitly acknowledging this connection. In his work “De docta ignorantia,” Cusanus attributes Maimonidean passages to a “Rabbi Solomon” rather than directly to Maimonides or Eckhart2. This caution may have been due to the controversial nature of some of Eckhart’s teachings, which had faced ecclesiastical censure.

Despite this caution, the intellectual thread connecting Maimonides, Eckhart, and Cusanus is clear. Eckhart’s mediation allowed Cusanus to engage with Jewish philosophical ideas within a Christian context, ultimately contributing to his unique synthesis of Neoplatonic, scholastic, and humanist thought3. This intellectual lineage demonstrates the complex interplay between Jewish and Christian philosophical traditions in the late medieval and early Renaissance periods, with Meister Eckhart serving as a crucial bridge between these traditions.

3 sources

Christian Neoplatonism Roots

Nicholas of Cusa’s philosophical framework was deeply rooted in Christian Neoplatonism, a tradition that significantly shaped his approach to theology and metaphysics. This intellectual lineage can be traced back to influential figures such as Proclus and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, whose works profoundly impacted Cusanus’s thought1.

Proclus, a 5th-century Neoplatonist philosopher, provided Cusanus with key concepts that he would later adapt and integrate into his Christian worldview. Cusanus’s engagement with Proclus’s work, particularly his commentary on Plato’s Parmenides, was facilitated by his encounter with Heimerich of Campo in Cologne1. This exposure to Proclean Neoplatonism offered Cusanus a sophisticated philosophical framework for contemplating the relationship between the One (or God) and the many (or creation).

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a mysterious 5th or 6th-century Christian theologian, was another crucial influence on Cusanus’s Neoplatonic leanings. Dionysius’s writings, which blended Christian theology with Neoplatonic philosophy, provided Cusanus with a model for synthesizing these two traditions. The Dionysian emphasis on negative theology and the ineffability of God resonated strongly with Cusanus, informing his doctrine of learned ignorance1.

Cusanus’s Christian Neoplatonism is particularly evident in his concept of the “coincidence of opposites” (coincidentia oppositorum). This idea, which posits that apparent contradictions are reconciled in the infinite nature of God, reflects the Neoplatonic notion of the One as transcending all oppositions. Cusanus ingeniously applied this concept to Christian theology, using it to explore the mysteries of the Trinity and the Incarnation2.

Furthermore, Cusanus’s understanding of the relationship between God and creation was deeply influenced by Neoplatonic emanationism. However, he modified this concept to align with Christian doctrine, emphasizing God’s free act of creation rather than a necessary emanation. This synthesis allowed Cusanus to maintain the Neoplatonic idea of the world as a manifestation of divine unity while affirming the Christian belief in God’s transcendence and freedom2.

Cusanus’s engagement with Christian Neoplatonism also led him to develop a unique epistemology. His notion of “learned ignorance” (docta ignorantia) draws on the Neoplatonic tradition of emphasizing the limitations of human knowledge in comprehending the divine. However, Cusanus transformed this idea into a positive approach to knowledge, suggesting that recognizing our ignorance is the first step towards true wisdom1.

By grounding his thought in Christian Neoplatonism, Cusanus was able to create a philosophical system that bridged medieval and Renaissance thought. His work demonstrates how the Neoplatonic tradition could be creatively reinterpreted to address the theological and philosophical challenges of his time, paving the way for new developments in European intellectual history.

2 sources

Christian Neoplatonism and Jewish Philosophy

Nicholas of Cusa’s philosophical synthesis uniquely blended Christian Neoplatonism with elements of Jewish philosophy, creating a rich intellectual tapestry that bridged multiple traditions. This integration was particularly evident in his approach to negative theology and the concept of divine infinity.

Cusanus’s engagement with Jewish philosophical ideas, especially those of Maimonides, complemented and enhanced his Neoplatonic framework. Maimonides’ emphasis on the unknowability of God’s essence resonated strongly with the Neoplatonic concept of the ineffable One1. Cusanus adapted this idea, integrating it into his doctrine of learned ignorance (docta ignorantia), which posits that true wisdom comes from recognizing the limitations of human knowledge in comprehending the divine2.

The influence of both traditions is apparent in Cusanus’s treatment of divine names and attributes. Like Maimonides, he stressed the inadequacy of positive attributes in describing God. However, Cusanus went further, employing the Neoplatonic concept of coincidentia oppositorum (coincidence of opposites) to argue that seemingly contradictory attributes could be reconciled in the infinite nature of God3. This approach allowed him to maintain the Christian doctrine of the Trinity while acknowledging the philosophical challenges it presented.

Cusanus’s cosmological views also reflect this synthesis. While drawing on the Neoplatonic concept of emanation, he modified it to align with the Christian doctrine of creation ex nihilo. At the same time, he incorporated elements reminiscent of Kabbalistic thought, such as the idea of the universe as an unfolding of divine potentiality4. This perspective allowed him to view the cosmos as both distinct from and intimately connected to God, a notion that resonated with both Neoplatonic and Jewish mystical traditions.

In his efforts to promote interfaith dialogue, Cusanus drew on both Christian Neoplatonism and Jewish philosophy. His work “De pace fidei” (On the Peace of Faith) imagines a celestial council where representatives of various faiths seek common ground5. This approach reflects the Neoplatonic ideal of unity underlying diversity, while also echoing Maimonides’ rationalist approach to reconciling different religious traditions.

Cusanus’s engagement with Jewish thought went beyond mere philosophical borrowing. His interest in Hebrew language and exegesis, evident in his occasional references to Hebrew terms and concepts, reflects the broader Renaissance humanist emphasis on returning to original sources6. This linguistic engagement allowed him to enrich his Neoplatonic framework with insights from Jewish scriptural interpretation.

By integrating elements of Jewish philosophy into his Christian Neoplatonic framework, Cusanus created a unique intellectual synthesis that transcended traditional boundaries. This approach not only enriched his own philosophical system but also paved the way for more inclusive and dialogic approaches to theology and philosophy in the Renaissance period and beyond.

6 sources

The Search for ‘Dux Neutrorum’

Nicholas of Cusa’s quest for a complete text of Maimonides’ “Guide of the Perplexed” (known in Latin as “Dux neutrorum”) around 1450 marked a significant moment in his intellectual journey and engagement with Jewish thought. This search demonstrates Cusanus’s deep interest in Jewish philosophy and his commitment to accessing primary sources.

The “Dux neutrorum” was a Latin translation of Maimonides’ seminal work, which had been circulating in Christian intellectual circles since the 13th century. However, complete and accurate copies were rare. Cusanus’s determination to find a full text speaks to the importance he placed on Maimonides’ ideas1.

After an extensive search, Cusanus located a copy of the “Dux neutrorum” in a Dutch monastery. This discovery was significant enough that he ordered a transcription to be made for Pope Nicholas V2. The pope’s involvement underscores the perceived value of Maimonides’ work not just for Cusanus personally, but for broader Christian intellectual discourse.

Cusanus’s search for the “Dux neutrorum” aligns with the Renaissance humanist emphasis on returning to original sources. By seeking out Maimonides’ text directly, rather than relying solely on Christian interpretations, Cusanus demonstrated a commitment to engaging with Jewish thought on its own terms3.

The impact of this search is evident in Cusanus’s later works. His familiarity with Maimonides’ ideas, particularly those concerning the limits of human knowledge in understanding the divine, became more pronounced and nuanced. This influence is especially apparent in Cusanus’s development of his doctrine of “learned ignorance” (docta ignorantia)4.

Interestingly, despite his efforts to obtain a complete text, Cusanus continued to attribute Maimonidean ideas to “Rabbi Solomon” in some of his writings. This practice may reflect a complex negotiation between his genuine interest in Jewish thought and the potential sensitivities surrounding direct citation of non-Christian sources2.

Cusanus’s search for the “Dux neutrorum” represents a pivotal moment in the transmission of Jewish philosophical ideas into Christian thought during the Renaissance. It exemplifies the intellectual curiosity and cross-cultural engagement that characterized this period of European history, paving the way for more extensive dialogue between Jewish and Christian philosophical traditions5.

5 sources

Impact on Renaissance Thought

Nicholas of Cusa’s innovative ideas had a profound impact on Renaissance thought, influencing fields ranging from philosophy and theology to mathematics and cosmology. His concept of “learned ignorance” (docta ignorantia) challenged the prevailing Aristotelian-Scholastic worldview and anticipated key insights of modernity1. This approach, which emphasized the limits of human knowledge while encouraging intellectual curiosity, resonated with Renaissance humanists and helped pave the way for new modes of inquiry.

In the realm of cosmology, Cusanus’s speculations about an infinite universe and the relativity of motion were groundbreaking. Although not based on empirical observations, his ideas that the universe had no center or circumference and that the Earth was not the fixed center of creation challenged traditional cosmological models2. These concepts, while not immediately adopted, laid important groundwork for later astronomical developments, including those of Copernicus and Galileo.

Cusanus’s mathematical ideas, particularly his work on squaring the circle and his explorations of infinity, contributed to the Renaissance revival of mathematics3. His approach to mathematics as a means of approaching divine truth influenced later thinkers and helped elevate the status of mathematics in Renaissance intellectual culture.

In the sphere of political thought, Cusanus’s writings on ecclesiastical reform and his concept of “concordance” (concordantia) in his work “De concordantia catholica” had significant implications. His ideas about consent and representation in church governance influenced later discussions about political authority and laid some of the groundwork for modern concepts of representative government4.

Cusanus’s efforts to reconcile different religious traditions, as exemplified in his work “De pace fidei,” resonated with Renaissance humanist ideals of universal wisdom and religious tolerance. This approach to interfaith dialogue and the search for common ground among different belief systems was an important contribution to Renaissance intellectual culture5.

His synthesis of Neoplatonic philosophy with Christian theology, enriched by elements of Jewish thought, created a unique intellectual framework that influenced subsequent Renaissance thinkers. This approach, which sought to harmonize diverse intellectual traditions, exemplified the Renaissance ideal of syncretism and contributed to the period’s rich intellectual ferment6.

Cusanus’s emphasis on the value of empirical observation and measurement, particularly in his work “Idiota de staticis experimentis,” aligned with the growing Renaissance interest in practical knowledge and experimentation. While not a scientist in the modern sense, his advocacy for precise measurement and observation in understanding the natural world contributed to the development of Renaissance scientific thought1.

Through these diverse contributions, Nicholas of Cusa emerged as a pivotal figure in the transition from medieval to Renaissance thought, helping to shape the intellectual landscape of early modern Europe.

6 sources

Mystical Theology in Cusanus

Nicholas of Cusa’s mystical theology represents a unique synthesis of Neoplatonic philosophy, Christian doctrine, and contemplative practice. At the heart of his mystical thought is the concept of “learned ignorance” (docta ignorantia), which paradoxically asserts that the highest form of knowledge is the recognition of one’s inability to fully comprehend the divine1. This approach aligns with the apophatic tradition in Christian mysticism, emphasizing the ineffability and transcendence of God.

Cusanus’s mystical theology is particularly evident in his work “De visione Dei” (On the Vision of God), which serves as both a theoretical treatise and a practical guide to mystical experience2. In this text, Cusanus employs the metaphor of vision to explore the relationship between human perception and divine reality. He posits that seeing God is ultimately identical to being seen by God, a concept that collapses the distinction between subject and object in mystical union2.

Central to Cusanus’s mystical thought is the idea of the “coincidence of opposites” (coincidentia oppositorum), which suggests that apparent contradictions are reconciled in the infinite nature of God3. This concept allows Cusanus to navigate the paradoxes inherent in mystical experience, such as the simultaneous transcendence and immanence of the divine.

Cusanus’s mystical theology also incorporates elements of Christology, interpreting the Neoplatonic theory of form through the lens of Christ as the divine exemplar2. This Christocentric approach distinguishes Cusanus’s mysticism from purely philosophical contemplation, grounding it firmly in Christian tradition while still engaging with broader philosophical concepts.

The influence of earlier mystics, particularly Pseudo-Dionysius, Meister Eckhart, and possibly Jan van Ruusbroec, is evident in Cusanus’s mystical writings2. However, Cusanus develops these influences in novel ways, emphasizing the cognitive element within an otherwise negative theology. This cognitive emphasis reflects Cusanus’s broader interest in the nature of knowledge and perception.

Cusanus’s mystical theology had a significant impact on later Renaissance thought, influencing both philosophical and religious discourse. His integration of mystical experience with rational inquiry anticipated later developments in Western spirituality and philosophy, bridging medieval mysticism with early modern approaches to knowledge and faith4.

4 sources

Philosophical Synthesis in Theology

Nicholas of Cusa’s philosophical synthesis in theology represents a unique fusion of diverse intellectual traditions, creating a framework that bridged medieval scholasticism and Renaissance humanism. At the core of his theological approach was the integration of Neoplatonic concepts, Christian doctrine, and elements of Jewish philosophy, particularly from Maimonides.

Cusanus’s concept of “learned ignorance” (docta ignorantia) exemplifies this synthesis. While rooted in the Neoplatonic tradition of emphasizing the ineffability of the divine, it also incorporates Maimonides’ emphasis on the limitations of human knowledge in comprehending God’s essence1. This concept allowed Cusanus to approach theological questions with a nuanced understanding that acknowledged both the pursuit of knowledge and its inherent limitations.

The principle of “coincidence of opposites” (coincidentia oppositorum) further demonstrates Cusanus’s philosophical synthesis. This idea, which posits that apparent contradictions are reconciled in the infinite nature of God, draws on Neoplatonic notions of divine unity while addressing Christian theological challenges, such as reconciling God’s justice and mercy2. It also resonates with certain aspects of Jewish mystical thought, particularly Kabbalistic concepts of divine attributes.

Cusanus’s approach to the relationship between faith and reason reflects his synthetic methodology. Unlike the strict separation often maintained in scholastic thought, Cusanus sought to harmonize faith and reason, viewing them as complementary paths to understanding the divine. This approach aligns with the Renaissance humanist ideal of integrating different modes of knowledge3.

In his cosmological thinking, Cusanus blended theological concepts with mathematical and philosophical ideas. His speculation about an infinite universe, while rooted in theological considerations about God’s infinitude, also drew on mathematical concepts and challenged prevailing Aristotelian cosmology. This synthesis anticipated later developments in Renaissance and early modern scientific thought4.

Cusanus’s engagement with interfaith dialogue, particularly in his work “De pace fidei,” demonstrates his ability to apply his philosophical synthesis to practical theological issues. By seeking common ground among different religious traditions, Cusanus employed his concept of learned ignorance to promote a more inclusive approach to theological understanding5.

The influence of Meister Eckhart’s Christian mysticism is evident in Cusanus’s work, but he develops these ideas in novel ways. Cusanus integrates Eckhartian mystical concepts with more rationalistic philosophical approaches, creating a unique form of speculative mysticism that bridges contemplative practice and intellectual inquiry1.

Cusanus’s philosophical synthesis in theology had a lasting impact on Renaissance thought, influencing later thinkers in their approach to reconciling faith, reason, and mystical experience. His work demonstrates the potential for creative integration of diverse intellectual traditions in addressing theological questions, setting a precedent for future developments in Western philosophical theology.

5 sources

ALL IMAGES MICROSOFT DIRECTOR AI