Companion Video on our YouTube Channel

Rachav – Foundation – YouTube

Prolegomena

Based on my summary of Gedaliahu A. Guy Stroumsa’s Another Seed: Studies in Gnosticism provides an academic investigation into the intricate landscape of Gnostic mythology, with a particular emphasis on the Sethian tradition. The work explores how Gnostics reframed biblical narratives to address the origins of evil, the nature of a flawed demiurge, and the possibility of spiritual liberation through sacred knowledge. Stroumsa argues that these myths represent a sophisticated syncretism of Jewish, Hellenistic, and early Christian thought, positioning Seth as a central figure of salvation. By examining the dualism between the material prison and the divine soul, the author illustrates how Gnosticism functioned as a radical philosophical system during Late Antiquity. The analysis further traces the enduring legacy of these ideas through their influence on Manichaeism and Hermeticism. Ultimately, the sources highlight Gnosticism’s role as a unique mythological phenomenon that challenged traditional religious orthodoxy.

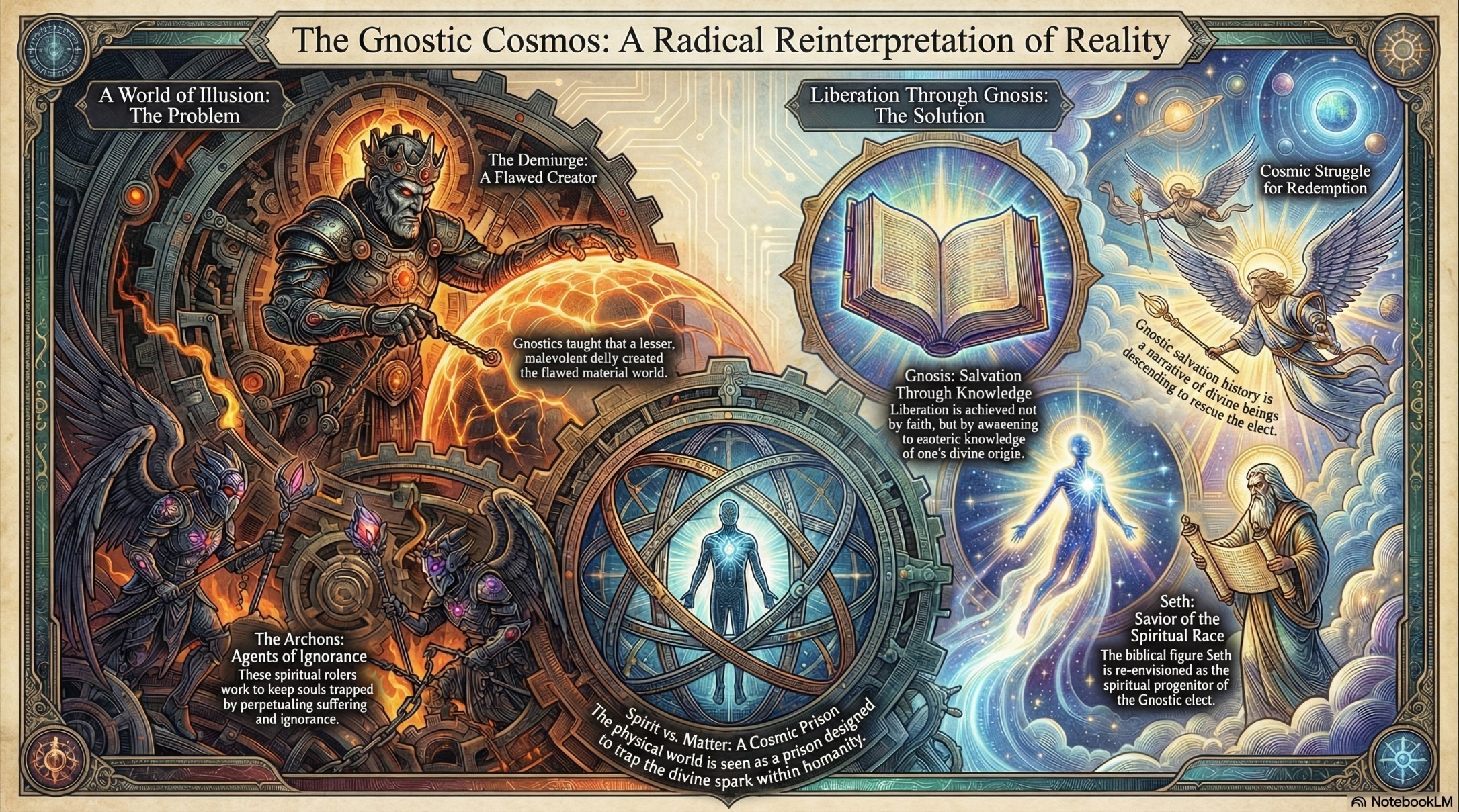

The central image of mechanical gears and celestial orbits surrounding a golden seed introduces the core tension of Gnostic thought: the friction between the complex, deterministic machinery of the material world and the singular, divine potential of the soul

Gnosticism as Mythological Innovation

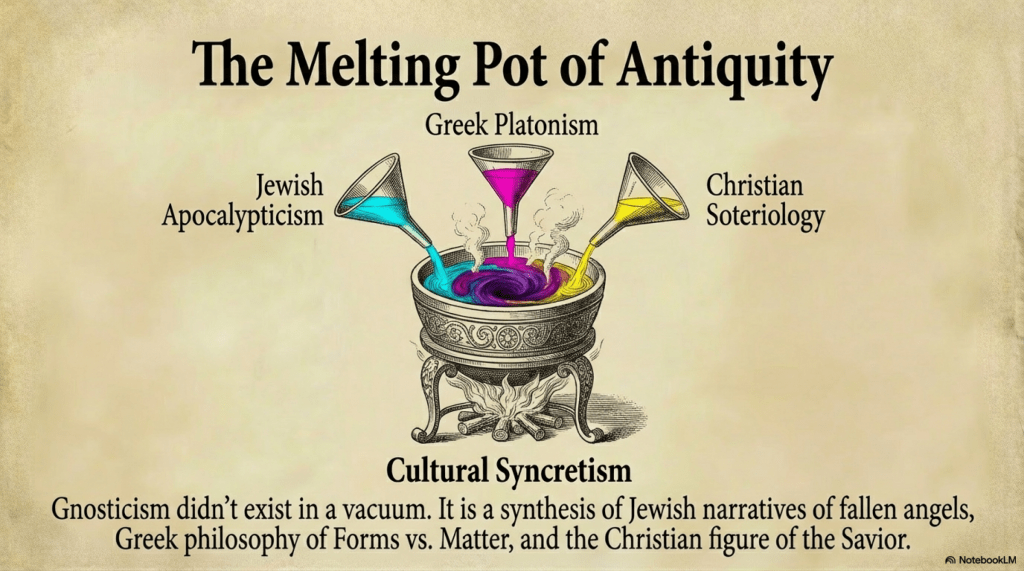

Stroumsa argues that Gnosticism is a sui generis (unique) phenomenon. Rather than being a simple corruption of Christianity or a fringe Jewish sect, it is a creative mythological response to existential despair. It represents the final major “outburst” of mythical thought in antiquity, born from the intellectual collision of Jewish apocalypticism and Greek philosophy

The Material Prison

Fundamental to the Gnostic worldview is Dualism. The material world is viewed as fundamentally flawed because its creator, the Demiurge, is himself flawed. Unlike the benevolent God in Genesis, the Demiurge is portrayed as malevolent, ignorant, or arrogant—a being who inadvertently or maliciously traps divine souls within the “prison” of matter.

Architects of Enslavement (The Archons)

The “Rulers” of this world, known as Archons, are depicted as celestial jailers rather than angels of light. Their primary objective is to keep humanity in a state of “sleep,” ignorant of their true divine origins. Stroumsa notes that these figures often embody the deterministic forces of the zodiac and planetary fate.

Inverting Genesis

Gnosticism performs a radical reversal of the Genesis narrative. In this “counter-history,” the Serpent and Eve are recontextualized as heroic figures who bring gnosis (wisdom) to humanity against the wishes of a jealous Demiurge. Evil is not the result of a human “fall,” but originates with the Creator God himself.

The Savior of ‘Another Seed’

Seth, the third son of Adam, is elevated to a divine savior figure and the prototype for the “Gnostic Race”. Sethians view themselves as “Another Seed,” a spiritual elect distinct from the material lineages of Cain and Abel. They are the “immovable race” destined for eventual salvation.

Traditions of Dissent (Sethianism vs. Valentinianism)

The presentation distinguishes between two major Gnostic traditions:

- Sethianism: Represents a “hard” dualism that demonizes the creator and focuses on the figure of Seth. Stroumsa identifies this as the core mythology.

- Valentinianism: A “softer,” more philosophical dualism that is closer to mainstream Christianity and views the Demiurge with less hostility.

The distinction between Sethian and Valentinian dualism represents the shift from a radical, “protest” mythology to a more systematic, philosophical framework within Gnostic thought. While both groups shared a fundamental belief in a divine origin for humanity, their interpretations of the material world and its creator differed significantly.

Sethianism: The Radical “Hard” Dualism

Sethianism is considered by Stroumsa to be the foundational “core” of Gnostic mythology, characterized by a sharp, uncompromising rejection of the material world.

- View of the Demiurge: The creator (Demiurge) is viewed with extreme hostility, often described as malevolent, ignorant, or arrogant.

- Origin of Evil: Evil is rooted directly in the nature of the creator himself, marking a radical departure from traditional Jewish narratives where evil results from a human fall or fallen angels.

- The Savior Figure: Seth, the third son of Adam, serves as the divine prototype and savior for the “spiritual elect,” known as the “immovable race.

- Goal: The focus is on a “rescue mission” to awaken divine sparks and liberate them from the “material prison” created by the Archons.

Valentinianism: The Philosophical “Soft” Dualism

Valentinianism emerged later as a more refined and intellectually accessible version of Gnosis, often seeking a closer relationship with mainstream Christianity.

- View of the Demiurge: The Demiurge is treated with far less hostility than in Sethianism; he is often seen as a tool of a higher divine power or simply unformed in his understanding, rather than purely evil.

- Nature of the World: The material world is not merely a prison but a realm that requires “formation” or perfection.

- Philosophical Synthesis: This tradition leans more heavily into Greek philosophy, attempting to bridge the gap between the divine Fullness (Pleroma) and the material realm through complex layers of divine beings (Aeons).

- Goal: Salvation is viewed less as a radical escape and more as a sophisticated process of achieving gnosis (knowledge) and reintegrating the soul into the divine order.

Summary of Differences

| Feature | Sethianism (The Radical) | Valentinianism (The Philosophical) |

| Creator (Demiurge) | Malevolent or Arrogant | Ignorant or “Unformed” |

| Dualism Style | “Hard” and Hostile | “Softer” and Philosophical |

| Primary Savior | Seth | Often a Gnostic Christ |

| View of the World | A “prison” for the soul | A realm needing refinement |

Sacred Geography

Gnostics projected their complex mythology onto the physical world, creating a metaphorical territory. Traditional concepts like the “Holy Land” were reinterpreted as metaphors for esoteric knowledge. For instance, locations like the “Land of Seir” were specifically associated with the preservation of Sethian wisdom

Salvation History (The Descent of Light)

In Gnostic thought, salvation is not a payment for sin but a rescue mission. Divine beings called Aeons descend from the Pleroma (the Fullness) to awaken the “sleeping sparks of light” within humanity. Salvation is achieved through gnosis—the realization of one’s divine origin and the breaking of the amnesia imposed by the Archons.

Paradoxes of Purity

While Gnostic myths often used sexual language to describe the corruption of the material world (such as seduction by Archons), Stroumsa rebuts claims that Gnostics practiced “orgies”. Instead, he argues the texts actually preach extreme asceticism, requiring the Gnostic to reject the material world to remain pure.

Case Study: Norea

Norea, appearing as the wife or sister of Noah or Seth, serves as a powerful figure of resistance. In Gnostic myth, she burns down Noah’s Ark because it represents the Demiurge’s plan to perpetuate human slavery. She symbolizes the Gnostic soul fighting against the oppressive “systems” of the material world.

The Melting Pot of Antiquity

Gnosticism did not emerge in isolation. It is a sophisticated cultural syncretism that synthesized:

- Jewish Apocalypticism: Narratives of fallen angels and cosmic conflict.

- Greek Platonism: The philosophical divide between the world of Forms and Matter.

- Christian Soteriology: The concept of a divine Savior.

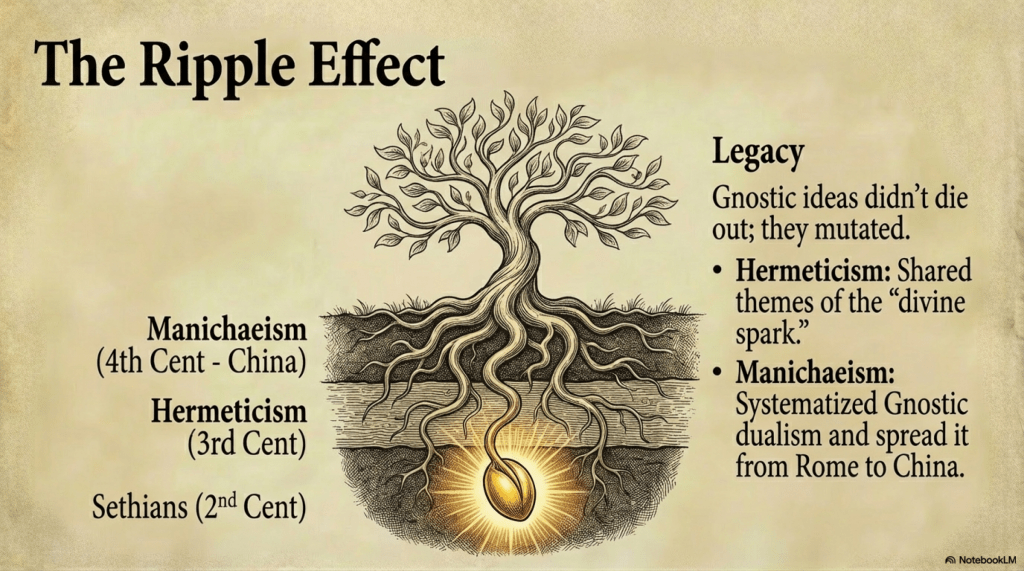

The Ripple Effect (Legacy)

Gnostic ideas did not vanish; they mutated and influenced later traditions. Hermeticism shared themes of the “divine spark,” while Manichaeism systematized Gnostic dualism and spread it as far as China.

Engaging the Scholarship

Stroumsa’s primary contribution is identifying the Sethian core and contextualizing these myths as a response to existential despair. While some scholars argue this focus might overshadow other Gnostic groups, Stroumsa points to the Nag Hammadi library as the essential key to understanding this “counter-history”.

15: The Enduring Question

Ultimately, Another Seed reveals Gnosticism as a radical, creative protest against a broken world. Stroumsa invites readers to view these myths not as “dead heresies,” but as a profound psychological map of the human condition that continues to resonate in eras of existential despair.

An In-depth Audio Amplifying the Concepts Raised in this Presentation

Monograph: A Radical Reinterpretation — Gnostic Mythology as the Culmination of Ancient Mythical Thought

1.0 Introduction: Situating Gnosticism in Late Antiquity

In the complex religious landscape of Late Antiquity, Gnosticism emerged not as a mere derivative heresy of nascent Christianity or Judaism, but as a distinct and profoundly innovative mythological phenomenon. Synthesizing the foundational research of Gedaliahu A. Guy Stroumsa, this monograph argues that Gnosticism represents a unique and creative force that radically reinterpreted established Jewish and Hellenistic narratives to construct a powerful and cohesive dualistic cosmology. Gnostic thinkers did not simply borrow from antecedent traditions; they actively reshaped them, inverting moral frameworks and challenging conventional understandings of creation, evil, and salvation. As Stroumsa’s analysis reveals, Gnosticism stands as the “last significant outburst of mythical thought in antiquity,” a testament to the enduring power of myth to articulate profound theological and existential questions in a world marked by cultural syncretism and spiritual searching. This monograph, therefore, interrogates the core tenets of this worldview, tracing its narrative origins, its conception of humanity’s divine lineage, and its unique path to liberation.

2.0 The Gnostic Cosmos: Dualism and the Malevolent Creator

The revolutionary nature of Gnostic mythology, and its definitive break from antecedent traditions, is nowhere more apparent than in its radical cosmology—a dualistic framework predicated on the malevolence of the material world and its creator. The Gnostic worldview is not merely a philosophical system but a dramatic cosmic narrative that explains the flawed nature of existence and humanity’s place within it. It is this framework that represents Gnosticism’s most significant departure from the antecedent traditions upon which it drew.

The Demiurge: An Ignorant Architect

At the heart of Gnostic cosmology is the figure of the demiurge, a creator-god who is fundamentally flawed, malevolent, or, most damningly, ignorant. This portrayal stands in stark opposition to the benevolent, omnipotent creator of mainstream Jewish and Christian theology. The Gnostic demiurge is the architect of the physical cosmos, and in his imperfection, he embodies the inherent evil and suffering of the material world itself. Crucially, this was not a world created in goodness and fallen through human sin, but a fundamentally corrupt construction from its very inception, the product of a lesser divinity who, in his cosmic ignorance, falsely believed himself to be the ultimate God. This error underpins the Gnostic imperative for revelatory gnosis—the knowledge that shatters the demiurge’s cosmic lie.

The Material World as a Prison

Flowing from this concept, Gnostics viewed the material world not as a home but as a prison for the divine spark, a luminous element of the true, transcendent God that has become trapped within the human body. The soul’s entanglement in matter—in the flesh and its passions—is the source of suffering and ignorance. This profound theological dualism, which pits spirit against matter and light against darkness, resonated deeply with the socio-political context of Late Antiquity. The Gnostic worldview was shaped by an environment of cultural syncretism and existential despair, where the experience of life under oppressive regimes could easily be framed as a form of cosmic imprisonment from which spiritual liberation was the only meaningful escape.

This conception of a flawed creation, governed by an ignorant creator, raises a critical question: how did this cosmic error and the evil it spawned originate?

3.0 Reframing Evil: From Apocalyptic Literature to Gnostic Myth

Gnosticism did not invent the problem of evil, a theological quandary long contemplated by its predecessors. Instead, it radically transformed the narrative of evil’s origins, drawing heavily upon the rich imagery of Jewish apocalyptic literature but ultimately subverting its conclusions. Gnostic thinkers took existing myths of cosmic rebellion and wove them into a new, more comprehensive explanation for the inherent corruption of the material world and the forces that perpetuate it.

From Fallen Angels to Cosmic Antagonists

As Stroumsa’s research reveals, there exists a clear thematic continuity between Jewish apocalyptic texts and Gnostic myths, particularly concerning the rebellion of divine beings. Gnostic narratives, however, amplified these stories to an entirely new scale. Figures like Azazel and the fallen angels, who in Jewish traditions were secondary agents of corruption, were elevated in Gnostic cosmology to become key players in the primordial cosmic drama. Their fall was not merely a transgression within a good creation but a foundational event that helped establish the corrupt rule of the demiurge and his celestial minions over the material realm.

The Inversion of the Genesis Narrative

Perhaps the most audacious Gnostic reinterpretation was its deconstruction of the Book of Genesis. Established moral frameworks were systematically inverted to fit the Gnostic dualistic worldview. For example, rather than being a passive victim or the origin of sin, Eve is often repositioned as an active and heroic participant in the drama of enlightenment. She is frequently depicted as a spiritual helper to Adam, awakening him to the Gnostic truth and working against the designs of the flawed creator. In this reframing, the serpent’s promise of knowledge is seen not as a temptation to sin but as a first step toward liberation.

The Archons: Guardians of the Prison

In the Gnostic cosmos, the malevolent will of the demiurge is enforced by a host of spiritual rulers known as the archons. These are not merely cosmic jailers but the very guardians of the planetary spheres, whose function is to obstruct the soul’s ascent back to the divine. Portrayed as seducers and oppressors, they work tirelessly to keep humanity trapped in ignorance and the material world, purveying the worldly passions and attachments that bind the divine spark to the prison of the flesh. The struggle for salvation, therefore, is a direct combat against the influence and power of these archons.

The establishment of such a vast cosmic tyranny, enforced by the archons, demanded more than a simple path to salvation; it required the mythological delineation of an entire spiritual race, innately opposed to the demiurge’s creation.

4.0 The ‘Another Seed’: Seth, the Spiritual Race, and Gnostic Identity

To establish a distinct identity within a hostile cosmos, Gnostic communities constructed a powerful mythological lineage that set them apart from the rest of humanity. This concept of a “Gnostic race” or “another seed” provided adherents with a clear origin story, a divine pedigree, and a mythological justification for their unique access to salvation. It was not a lineage of blood, but of spirit, tracing its origins back to a key figure reinterpreted from the Hebrew scriptures.

Seth: Progenitor of the Spiritual Elect

Central to this mythology is Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve. In Gnostic thought, Seth is elevated from a comparatively minor biblical patriarch—a figure of genealogical, rather than salvific, importance in orthodox tradition—to become the prototype and progenitor of the “spiritual race.” As Stroumsa’s analysis demonstrates, Seth is recast as a salvific figure in his own right, a redeemer who embodies the divine spark passed down to a chosen few. He is the symbolic ancestor of the Gnostics themselves, who see themselves as the “sons of Seth,” carriers of the divine light in a world of darkness.

A Divergent ‘Son of God’

The Gnostic reinterpretation of Seth’s status as a “Son of God” provides a prime example of their method of appropriating and reframing biblical characters to align with their dualistic cosmology. While orthodox traditions might interpret this phrase genealogically or metaphorically, Gnostic traditions saw it as a literal statement of Seth’s divine nature, contrasting him with the material lineage of humanity. This elevation of Seth created a clear theological and social boundary, distinguishing the Gnostic community from both mainstream Judaism and Christianity.

A Race Apart

This distinction between the Sethian Gnostics and the “material race”—the rest of humanity created by the archons—is a core tenet of their identity. It reinforced their sense of alienation from the world and its creator, the demiurge, and solidified their belief that their destiny lay not within the material cosmos but in a transcendent realm of light. Their identity was not tied to earthly nations or laws but to a spiritual kinship that transcended the physical world.

This belief in a chosen spiritual race, stranded in a hostile world, formed the basis for a unique narrative of their ultimate rescue and liberation.

5.0 Gnostic Soteriology: Divine Intervention and Inverted Geography

Gnostic salvation, or soteriology, is fundamentally distinct from the models of atonement or righteous living found in mainstream traditions. Because the world itself is the problem, salvation cannot be achieved within it; rather, it requires a dramatic cosmic intervention to achieve liberation from it. The Gnostic path to redemption is therefore a story of rescue, revelation, and the soul’s arduous journey homeward to the transcendent realm of light.

A History of Divine Rescue

The Gnostic salvation history is framed as a narrative of divine intervention from the supernal world of the aeons. Gnostic texts are replete with accounts of divine beings descending into the material cosmos to aid the elect. Figures such as Abrasax and Sablo are depicted as emissaries from the true God, coming to rescue the “sons of Seth” from the clutches of the demiurge and his archons. This salvation comes not through faith or works in the traditional sense, but through gnosis—the revelatory knowledge of one’s true, divine origin and the path to escape the material prison.

The Inversion of Sacred Geography

This reinterpretation extends to the very concept of holy land. Gnostic traditions creatively recontextualized physical, biblical locations, transforming them into a mythical “sacred geography.” Stroumsa highlights how places like the land of Seir and Transjordan were appropriated and reimagined as a spiritual “holy land” for the descendants of Seth. This represents an inverted reflection of traditional eschatology. The promised land is no longer a physical territory to be inherited on Earth but a symbol of a spiritual state of being. In a perfect encapsulation of the Gnostic method, the biblical promise of “milk and honey” is reinterpreted to signify the richness of esoteric knowledge rather than physical prosperity. Spiritual enlightenment, therefore, replaces physical territory as the ultimate goal.

The Gnostic myth, with its intricate cosmology and soteriology, was not a static system but a dynamic one that interacted with and influenced other religious currents of the era.

6.0 Mythological Crossroads: Syncretism, Evolution, and Adaptation

Gnostic thought was not developed in isolation. As Stroumsa’s research demonstrates, its myths were dynamic and syncretic, constantly evolving as they absorbed and reinterpreted ideas from the diverse cultural and religious currents of Late Antiquity. Gnostic narratives were remarkably adaptable, allowing them to be modified and integrated into different systems of thought across the Mediterranean and Near East.

Sethianism and Valentinianism: An Evolving Tradition

Within Gnosticism itself, different traditions emerged with unique theological emphases. A comparison of Sethianism and Valentinianism reveals this evolutionary process.

| Sethianism | Valentinianism |

|---|---|

| Represents an earlier, foundational stratum of Gnostic mythology. | Represents a later, more philosophically sophisticated development. |

| Often features a starker, more radically dualistic cosmology. | Develops a more elaborate cosmology, often mapping psychic structures onto divine hierarchies. |

| Focuses heavily on Seth as the progenitor of the spiritual race. | Incorporates core Sethian themes but adapts them for a broader intellectual audience. |

| Provides the mythological framework for later Gnostic movements. | Builds upon and refines earlier Gnostic concepts into complex theological systems. |

Based on his textual analysis, Stroumsa argues that Sethianism represents a foundational stratum of Gnostic thought that heavily informed the later, more philosophically elaborate systems of Valentinianism. This relationship underscores the dynamic and developmental nature of Gnostic mythology over time.

Gnostic Echoes in Other Traditions

The influence of Gnostic ideas extended beyond its own communities, leaving a discernible mark on other religious and esoteric movements.

• Hermeticism: There is a clear intersection between Gnostic and Hermetic traditions. Both share core themes such as the concept of a divine spark trapped within the human being, the necessity of liberating knowledge (gnosis), and the narrative of the ascent of the soul through hostile planetary spheres to return to its divine source.

• Manichaeism: Manichaean myths provide a powerful case study in the adaptation of Gnostic themes. Mani, the founder of Manichaeism, incorporated and transformed existing Gnostic narratives into his own universalist religion. The Gnostic heroine Norea, a figure known for her fierce resistance to the archons, is a prime example. Her story, representing the struggle of the divine light against the forces of darkness, proved highly adaptable and found a new context within Manichaean mythology. Crucially, Norea may equally be viewed as representing the Gnostics themselves in their combat against the archons, transforming her from a mere character into a powerful archetype for the Gnostic community’s own identity and struggle.

This process of adaptation and evolution highlights Gnosticism’s role as a vital intellectual crossroads in Late Antiquity, leading to its enduring legacy.

7.0 Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Gnostic Myth

Gedaliahu Stroumsa’s scholarly work compellingly positions Gnosticism not as a footnote to history but as a unique and powerful mythological phenomenon in its own right. This monograph has synthesized his core thesis, demonstrating that Gnosticism was characterized by its radical and creative reinterpretation of Jewish and Hellenistic source materials. From this syncretic foundation, Gnostic thinkers constructed a cohesive and dramatic dualistic worldview that offered its adherents a profound explanation for suffering and a clear path to liberation. This was a system built on inversion—an ignorant creator, a heroic transgressor, and a salvation that meant escaping creation itself.

The intellectual and religious creativity of Gnosticism was remarkable, yielding a complex tapestry of myth that gave meaning to existence. This is nowhere more vividly illustrated than in the challenging paradoxes of the “Gnostic sexual myth,” where themes of creation and transgression are profoundly interwoven. In one striking midrashic example, we are told that “The pure maidens were born from the rape of Wise-of-Ages by the lustful archon.” It is precisely this capacity to generate purity from violation, alongside the paradoxical notion of the savior who requires salvation, that stands as a hallmark of Gnostic mythological creativity.

Stroumsa’s scholarship, therefore, is not merely a contribution to Gnostic studies; it is an indispensable key to unlocking the intricate theological landscape of Late Antiquity and appreciating Gnosticism as a radical and enduring monument to mythological thought.

Study Guide:

Gedaliahu A. Guy Stroumsa’s “Another Seed: Studies in Gnosticism”

This study guide provides a review of the key themes, arguments, and concepts presented in Gedaliahu A. Guy Stroumsa’s Another Seed: Studies in Gnosticism, based on a scholarly analysis and summary of the work. It includes a short-answer quiz, an answer key, suggested essay questions, and a glossary of important terms to facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the material.

——————————————————————————–

Quiz

Answer the following questions in 2-3 sentences each, based on the provided analysis of Stroumsa’s work.

1. What is Stroumsa’s central argument regarding the nature of Gnostic mythology?

2. Describe the role of the demiurge in Gnostic cosmology as presented in the book.

3. According to Stroumsa, what is the relationship between Sethian and Valentinian Gnosticism?

4. How did Gnostics reinterpret the problem of evil, departing from Jewish apocalyptic literature?

5. What is the significance of the biblical figure Seth within the Gnostic tradition?

6. Explain the function of the archons in Gnostic narratives.

7. What does the concept of “sacred geography” refer to in the context of Gnostic thought?

8. How does Stroumsa argue against the accusations of licentiousness made against Gnostics by early Church Fathers?

9. According to the analysis, what traditions were influenced by or shared themes with Gnosticism?

10. What are the key strengths of Stroumsa’s methodology in Another Seed?

——————————————————————————–

Answer Key

1. Stroumsa’s central argument is that Gnosticism constitutes a unique and innovative mythological phenomenon, not merely a derivative of Greek philosophical traditions or Hebrew prophetic literature. He posits that Gnosticism represents the “last significant outburst of mythical thought in antiquity,” culminating mythological creativity through its radical reinterpretation of foundational religious concepts.

2. The demiurge is portrayed as a flawed or malevolent creator figure who is responsible for the material world. This being traps the divine spark of humanity within this physical prison, creating a sharp dualism between the spiritual realm and the evil material world.

3. Stroumsa argues that the Sethian tradition represents an earlier, more foundational layer of Gnostic thought. He suggests that Sethianism informs the later developments found in Valentinianism, highlighting an evolution of Gnostic ideas over time.

4. Gnostics reframed the problem of evil as a cosmic drama involving divine beings and their rebellion. They amplified narratives from Jewish apocalyptic texts to portray the material world itself as the creation of malevolent archons, led by the demiurge, thus externalizing evil into the very fabric of creation.

5. In Gnostic mythology, Seth, the third son of Adam and Eve, is elevated to the status of a central salvific figure and a “Son of God.” He is considered the symbolic progenitor of the “Gnostic race,” a spiritual lineage distinct from the material race associated with the archons.

6. The archons are spiritual rulers who act as seducers and oppressors of humanity in Gnostic mythology. Their primary function is to keep the divine spark trapped within the material world, embodying the forces that keep humanity in a state of ignorance and suffering.

7. “Sacred geography” refers to the Gnostic practice of reinterpreting and recontextualizing biblical locations, such as the land of Seir, into a mythical “holy land.” This serves as an inverted reflection of traditional eschatology, where the Gnostic holy land symbolizes spiritual enlightenment rather than a physical territory.

8. Stroumsa contends that accusations of licentiousness stem from a misunderstanding of Gnostic texts by early Church Fathers. He argues that Gnostic writings actually emphasize a condemnation of lustful acts and articulate a deep spiritual struggle against the material world and its corrupting forces.

9. The analysis shows that Gnostic ideas influenced and interacted with other traditions, particularly Hermeticism and Manichaeism. Stroumsa demonstrates how key Gnostic myths and figures, such as Norea, were adapted and transformed within these later religious and esoteric contexts.

10. The key strengths of Stroumsa’s methodology are his careful textual analysis of a wide range of Gnostic sources and his interdisciplinary approach. He combines historical and philosophical methods to situate Gnostic thought within the broader cultural, intellectual, and socio-political milieu of Late Antiquity.

——————————————————————————–

Essay Questions

The following questions are designed for longer, essay-style responses. Answers are not provided.

1. Discuss Gedaliahu Stroumsa’s argument that Gnosticism represents a unique and innovative mythological phenomenon rather than being merely derivative of Jewish and Hellenistic traditions. Use specific examples from the text, such as the reimagining of the demiurge or the role of Seth, to support your analysis.

2. Analyze the concept of dualism in Gnostic thought as presented in Another Seed. How do figures like the demiurge and the archons embody this dualism, and what are the implications for the Gnostic view of the material world, the human condition, and salvation?

3. Explore the Gnostic reinterpretation of biblical figures and narratives, focusing on characters like Seth, Eve, Azazel, and Cain and Abel. How does Stroumsa explain the significance of these reinterpretations in shaping a distinct Gnostic identity and theology?

4. Based on the provided analysis and summary, evaluate the interdisciplinary nature of Stroumsa’s research. How does his integration of textual analysis, historical context, and comparative studies contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of Gnosticism?

5. Trace the influence and adaptation of Gnostic myths in later traditions such as Hermeticism and Manichaeism, as detailed in Stroumsa’s work. What does this “afterlife” of Gnostic ideas reveal about their adaptability and enduring appeal in the religious landscape of Late Antiquity?

——————————————————————————–

Glossary of Key Terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Abrasax | A figure in Gnostic narrative who, along with Sablo, helps rescue the Gnostics from the demiurge’s control. |

| Aeons | Divine realms or beings from which “great clouds of light” descend to aid the Gnostics. |

| Archons | Spiritual rulers in Gnostic cosmology depicted as malevolent seducers and oppressors. They work to keep the divine spark of humanity trapped in the material world. |

| Azazel | A figure from Jewish myth reinterpreted in Gnostic thought. He is described as a beast with a snake’s body and human members, symbolizing the struggle with temptation. |

| Demiurge | A central figure in Gnostic cosmology; a flawed, ignorant, or malevolent creator who fashioned the material world, which is seen as a prison for the divine spark. |

| Dualism | The core Gnostic worldview that posits a sharp opposition between the world of spirit and light (the divine) and the world of matter and darkness (the creation of the demiurge). |

| Gnostic Race | A concept referring to the spiritual lineage of the Gnostic elect, who are believed to have originated from Seth, distinguishing them from the “material race.” |

| Hermeticism | A religious and philosophical tradition of Late Antiquity that shared themes with Gnosticism, such as the ascent of the soul and the divine spark, suggesting mutual influence. |

| Manichaeism | A major religion founded by the prophet Mani that incorporated and transformed Gnostic themes, myths, and figures, such as the heroine Norea. |

| Nag Hammadi Texts | A collection of early Christian and Gnostic texts discovered in Egypt in 1945. They are a crucial primary source for Stroumsa’s study of Gnostic mythology. |

| Norea | A female archetype and Gnostic heroine who figures prominently in Manichaean myths. She represents the Gnostics themselves in their struggle against the archons. |

| Sablo | A figure in Gnostic narrative who, along with Abrasax, participates in the rescue of the Gnostics. |

| Sacred Geography | The Gnostic practice of reinterpreting biblical locations and mapping them onto a mythical landscape. This “holy land” symbolizes spiritual enlightenment rather than physical territory. |

| Seth | The third son of Adam and Eve. In Gnostic mythology, he is elevated from his biblical role to become a central salvific figure, a “Son of God,” and the progenitor of the Gnostic spiritual race. |

| Sethianism | A prominent and early strand of Gnostic thought that Stroumsa identifies as a foundational layer for later Gnostic developments, such as Valentinianism. |

| Syncretism | The synthesis of elements from different cultural, religious, and philosophical traditions. Stroumsa frames Gnosticism as a syncretic tradition combining Hellenistic, Jewish, and early Christian elements. |

| Valentinianism | A major school of Gnostic thought that Stroumsa argues developed from the earlier, foundational ideas of Sethianism. |

| Yaldabaoth | A Gnostic figure, often identified with the demiurge, whose name appears in both Gnostic and Hermetic traditions. |