1. Foundations of Rabbinic Literary Theory: From Philology to Poetics

CLICK ABOVE IMAGE FOR VIDEO

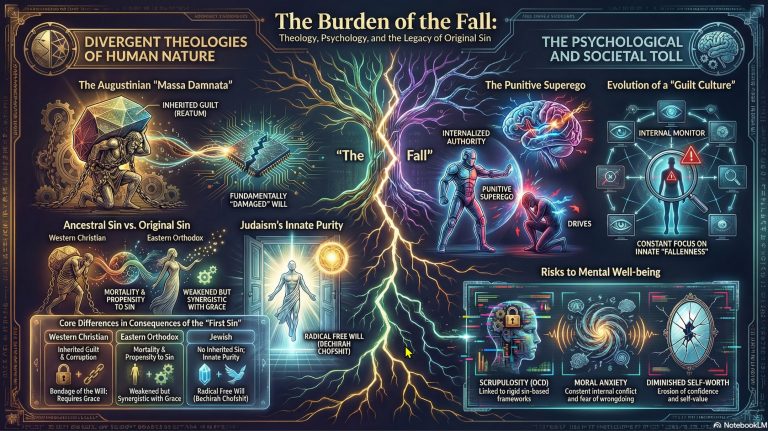

1.1 The Literary Turn in Rabbinic Studies

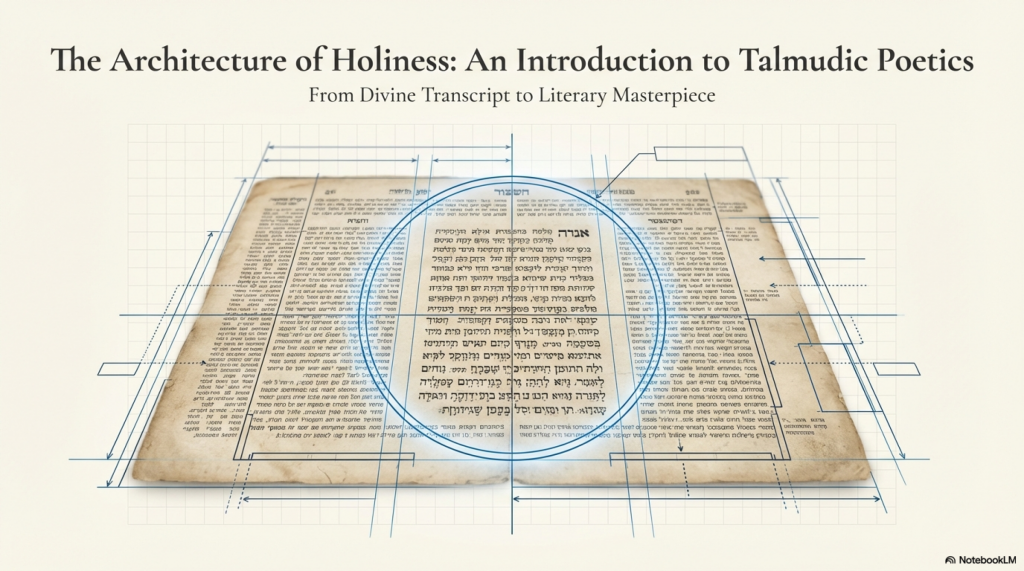

The academic study of Rabbinic literature—encompassing the Mishnah, Tosefta, Babylonian Talmud (Bavli), Jerusalem Talmud (Yerushalmi), and Midrashic corpora—has historically been dominated by two distinct methodological paradigms: traditional legal exegesis and historical philology. The former approached the text as a coherent, divinely sanctioned repository of Halakhah (law), engaging with its content to adjudicate religious practice. The latter, emerging with the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement in the 19th century, treated the text as an archive of historical data, mining it for linguistic artifacts, realia, and biographies of sages, often stripping away the “literary” accretions to find the “historical kernel.”

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries witnessed a “literary turn” in Rabbinic studies. Scholars began to recognize that these texts are not mere stenographic transcripts of academy debates or uncurated collections of folklore. Rather, they are highly constructed, sophisticated literary artifacts.1 This shift, often termed “Talmudic Poetics,” posits that the redactors (Stammaim) and compilers were active literary artists who employed specific rhetorical devices, narrative structures, and intertextual strategies to generate meaning.

The classification of Rabbinic literature defies easy categorization within Western genres. It is simultaneously a law code, a digest of case law, an encyclopedia of folk wisdom, a theological treatise, and a collection of homilies.1 While the term “Rabbinic literature” generally refers to the output of the sages (Chazal) from the destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE) to the Muslim conquest, the literary activity involved represents a complex evolution from oral traditions to crystallized texts.4 Understanding the poetics of this literature requires navigating the tension between the “text” as it appears on the page and its prehistory as oral discourse.1

1.2 Theoretical Frameworks: The Fraenkel-Rubenstein Debate

The field of Talmudic poetics has been significantly shaped by a methodological dialectic between synchronic literary analysis and diachronic source criticism. This debate is best exemplified by the divergent approaches of Yonah Fraenkel and Jeffrey Rubenstein regarding the Talmudic story (Aggadah).

Yonah Fraenkel established the study of Rabbinic narrative as a distinct discipline rooted in New Criticism. His approach views the Talmudic story as a “closed,” autonomous artistic unit. Fraenkel argues that a story provides all the information necessary for its own interpretation within its narrative boundaries.7 He focuses on the “close reading” of the text, analyzing structural patterns, leitmotifs, time-designations, and character psychology to uncover the spiritual world of the story.2 For Fraenkel, the literary artistry is internal to the story itself, and the primary task of the scholar is to explicate the aesthetic and thematic unity of the individual narrative unit, largely ignoring its redactional context within the sugya (discussion unit).7

In contrast, Jeffrey Rubenstein represents a synthesis of literary analysis with academic source criticism. Rubenstein argues that Talmudic stories cannot be understood in isolation from their redactional history. He emphasizes the role of the Stammaim—the anonymous redactors of the Babylonian Talmud—in reshaping earlier Palestinian traditions.2 Rubenstein’s method often involves a synoptic comparison between the Bavli’s narratives and their parallels in the Yerushalmi or Tosefta.

This synoptic comparison frequently reveals that the Bavli’s redactors did not merely transmit stories but actively rewrote them. They added dramatic dialogues, internal monologues, and complex character motivations that were absent in the earlier sources.8 For Rubenstein, the “poetics” of the Talmud is largely the poetics of the Stammaim, reflecting the values, anxieties, and academic culture of the Babylonian academies of the 5th and 6th centuries rather than the historical reality of the Tannaim or early Amoraim.8 Where Fraenkel sees a gap in the narrative as an intentional literary device inviting interpretation, Rubenstein might identify a “redactional seam”—a point where two disparate sources were imperfectly stitched together.7

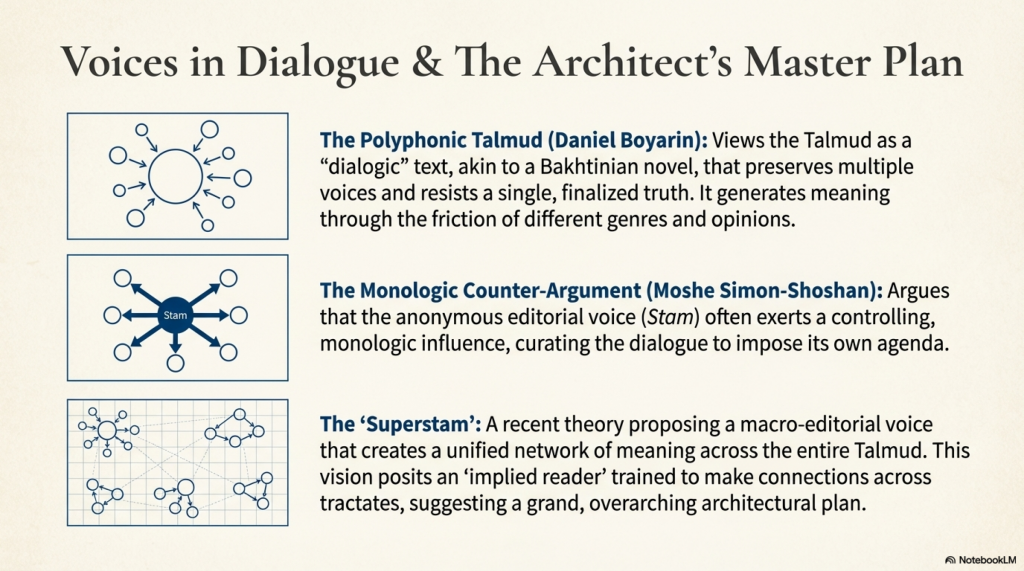

1.3 The Dialogic Text: Bakhtin and the Polyphonic Talmud

A third major theoretical strand applies the theories of Mikhail Bakhtin to Rabbinic literature, characterizing the Talmud as a “dialogic” text. Daniel Boyarin has been instrumental in this approach, arguing that the Talmud shares features with the Bakhtinian “polyphonic novel”.3 In works such as Carnal Israel and essays on the “Talmud as Novel,” Boyarin suggests that the Talmud’s structure—which preserves minority opinions, unresolved disputes, and the interplay of diverse voices—reflects a “Menippean satire” or a dialogic discourse that resists finalization.10

According to this view, the Talmudic text is not merely a repository of law but a “cultural poetics” where the boundaries between the “serious” and the “comic,” the “legal” and the “narrative,” are fluid.11 The juxtaposition of rigorous legal dialectic with grotesque humor, folklore, and seemingly irrelevant narrative creates a text that generates meaning through the friction between these genres.

However, this application of Bakhtin is not without its critics. Moshe Simon-Shoshan argues that while the Talmud appears polyphonic, the anonymous editorial voice (the Stam) often exerts a controlling, monologic influence.3 The Stam aggressively reinterprets earlier voices to suit its own agenda, suggesting that the “dialogue” is often a carefully curated literary construct rather than a free exchange of ideas. The Stam does not merely record the debate; it creates the debate, often fabricating dialogue between sages who lived centuries apart to serve a pedagogical or theoretical point.3

1.4 The “Superstam” and the Implied Reader

Recent scholarship has moved beyond the individual sugya to consider the poetics of the Bavli as a unified book. The concept of the “Superstam,” proposed in recent dissertations and studies, suggests an authorship that operates above the local Stammaitic editing.12 This macro-editorial voice utilizes rare terminology, unique phrasing, and intertextual cross-references to create a network of meaning across the entire Talmud.

This approach posits a specific “implied reader” of the Talmud—one who is expected to remember and correlate discussions from vastly different tractates. The poetics of the Bavli, therefore, involve a “pedagogy of reading,” where the text trains the student to identify key words and conceptual links that subvert or complicate the local certainty of a specific passage.12 This shifts the focus from the writer’s poetics to the reader’s poetics, where the text is “written by its own readers” through the act of complex transmission and cross-referencing.12

2. The Poetics of the Sugya in the Babylonian Talmud

The fundamental literary unit of the Talmud is the sugya (plural: sugyot). While ostensibly a transcript of legal debates, the sugya is a highly stylized literary form with a specific architecture, rhythm, and narrative logic.

2.1 Structural Patterns: Chiasmus and the Tripartite Form

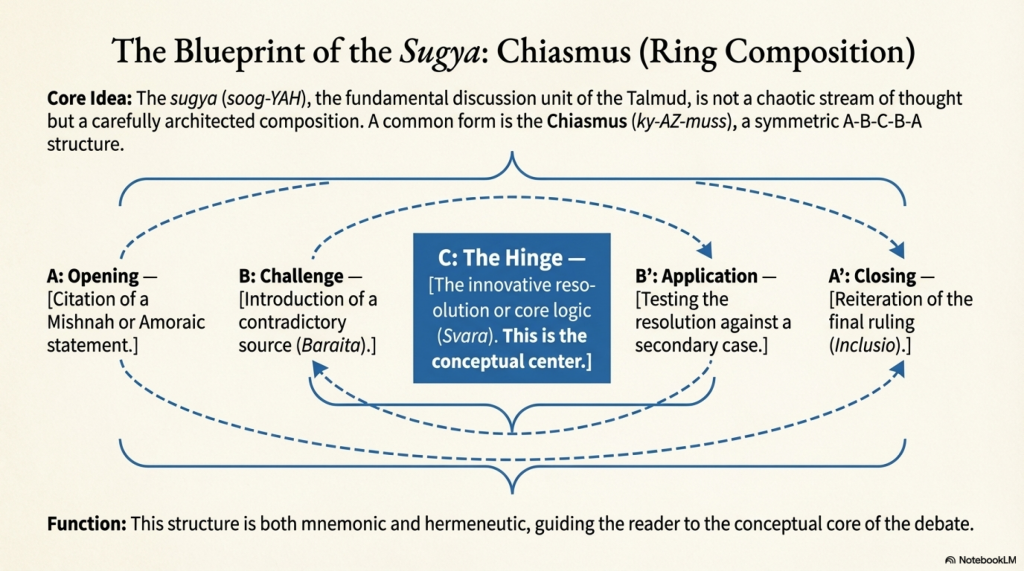

Shamma Friedman’s pioneering work on the structure of Talmudic sugyot demonstrated that they are not stream-of-consciousness records but carefully architected compositions.13 Friedman identified that many sugyot exhibit precise structural patterns, challenging the notion that the Talmud is associative or chaotic.

One of the most prevalent literary devices in the sugya is chiasmus (or ring composition). Chiasmus is a symmetric structure (A-B-B-A or A-B-C-B-A) used to emphasize the central element or to create a sense of closure.14 This structure is not unique to the Talmud; it is found in Biblical poetry and ancient epics like the Iliad, but the Talmud adapts it for legal dialectic.16

Table 1: The Chiastic Structure of a Standard Sugya

| Structural Component | Description | Rhetorical Function |

|---|---|---|

| A (Opening) | Citation of a Mishnah or Amoraic Statement. | Establishes the normative legal baseline. |

| B (Challenge) | Introduction of a contradictory Tannaitic source (Baraita). | Destabilizes the baseline; introduces conflict. |

| C (The Hinge/Center) | The Innovative Resolution / The “Svara” (Logic). | The theological or conceptual core of the unit. |

| B’ (Application) | Testing the resolution against a secondary case. | Re-stabilization; applying the new logic. |

| A’ (Closing) | Reiteration of the ruling or final legal outcome. | Inclusio (Closing the envelope); literary satisfaction. |

This chiastic structuring is not merely aesthetic; it is a mnemonic device and a hermeneutic signal.14 By placing the most critical innovation at the center (C), the redactors signal the hierarchy of values within the debate. For example, in narratives regarding the “feminine exemption” or the “repudiation of Aher,” the complex literary structure guides the reader to the intended moral conclusion.17

Friedman also identified the “tripartite structure” as a recurring form, where a sugya presents three distinct challenges or interpretations of a single law.13 This triad often follows a Hegelian-like progression of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, or an escalation of difficulty (easy objection $\rightarrow$ harder objection $\rightarrow$ fatal objection).

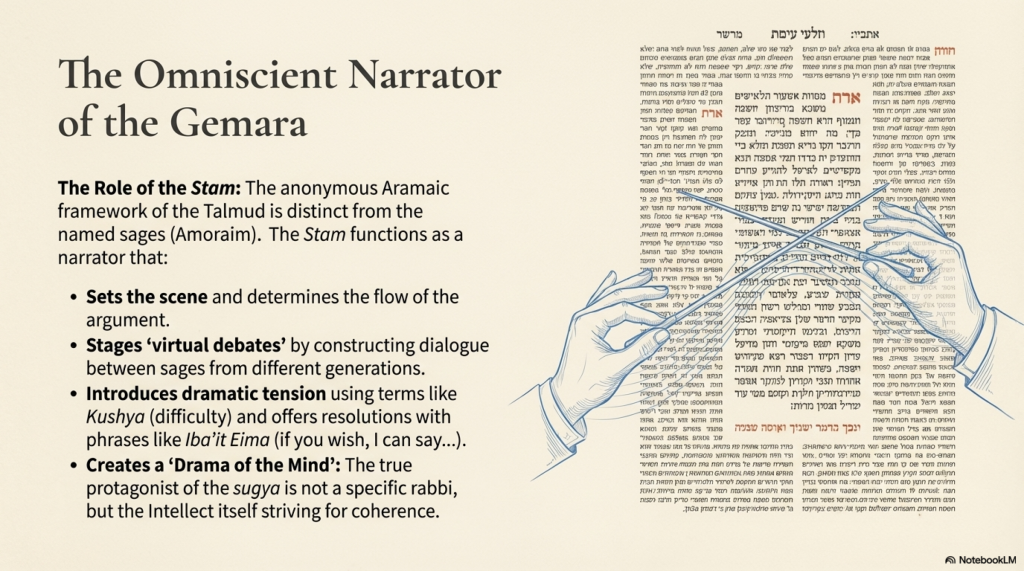

2.2 The Stammaitic Voice as Narrator

The distinction between the attributed statements of the Amoraim (named sages) and the anonymous dialectical framework (the Stam or Gemara) is central to understanding Bavli poetics. The Stam functions as an omniscient narrator. It sets the scene, interprets the laconic words of the earlier sages, and determines the flow of the argument.19

The Stam often utilizes a “reconstructive poetics,” taking two disparate statements from different generations and placing them in a constructed dialogue. This creates a “virtual” debate that never occurred historically but serves a pedagogical purpose.8 The Stam introduces terminology like Teyuvta (refutation), Kushya (difficulty), or Iba’it Eima (if you wish, I can say…) to pace the dramatic tension of the sugya.

This narrative voice is distinct from the named sages. While the Amoraim speak in brief, often apodictic rulings, the Stam speaks in a discursive, questioning, Aramaic dialect. The result is that the sugya functions as a “drama of the mind,” where the protagonist is not a specific rabbi, but the Intellect itself, struggling to reconcile contradictions and achieve coherence.19

2.3 Legal Narratives and the “Poetics of Indeterminacy”

Narrative episodes in the Bavli are rarely decorative; they serve a distinct function within the legal (Halakhic) argument. Barry Wimpfheimer’s analysis of “legal narratives” shows that stories are often deployed to undermine, nuance, or complicate the rigid abstract laws derived in the dialectic.20

A narrative might portray a rabbi acting against the stated law, introducing the concept of Lifnim mi-shurat ha-din (acting beyond the letter of the law) or demonstrating that the messiness of lived reality cannot be fully contained by statutory formulations.21 For example, in Bava Metzia, the Talmud may spend pages deriving strict laws of property, only to conclude with a story of a rabbi who returns property he was not legally obligated to return, privileging the narrative ethic over the legal statute.

This interplay creates a “poetics of legal indeterminacy,” where the text refuses to reduce law to a code, insisting instead on the narrative context of legal application.22 The inclusion of these narratives signals that the “Law” is not just the black-letter rule, but the behavior of the sage who embodies the law.

3. Narrative Art in the Bavli: The “Aggadah”

The Aggadah (narrative and non-legal portions) of the Bavli exhibits a high degree of literary sophistication, characterized by character development, irony, tragedy, and what Daniel Boyarin calls “grotesque realism.”

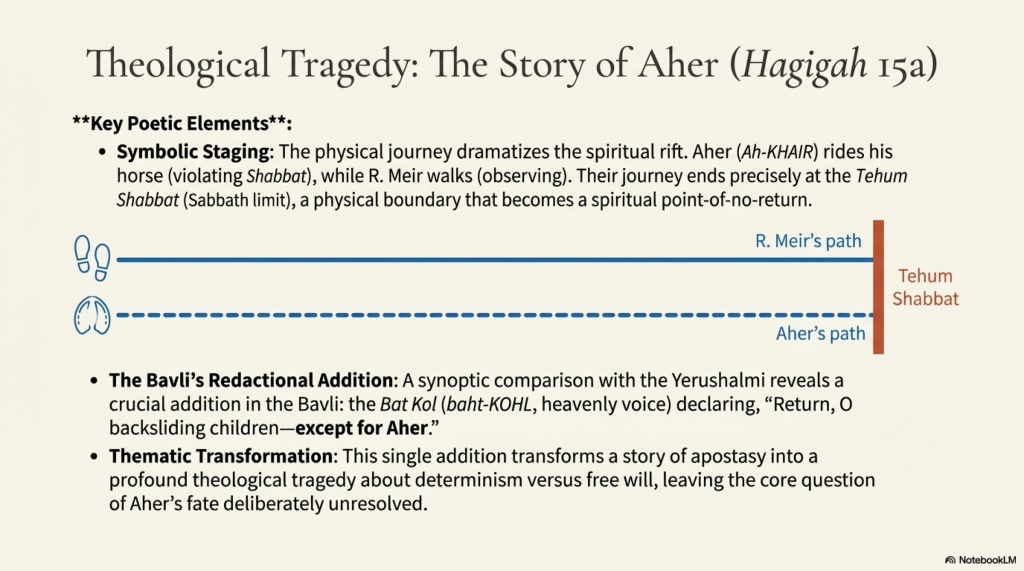

3.1 The Tragedy of the Intellectual: The Story of Aher

The narrative of Elisha ben Abuyah (known as Aher, “The Other”) in Hagigah 15a serves as a prime example of Bavli narrative art. The story depicts the sage riding a horse on the Sabbath while his disciple, Rabbi Meir, walks behind him learning Torah.

- Symbolism and Space: The spatial arrangement—one riding (violating Shabbat), one walking (observing Shabbat)—visually dramatizes the theological rift.7 The dialogue concludes at the Tehum Shabbat (Sabbath limit), where Aher tells Meir to return. This detail serves a dual poetic function: it demonstrates Aher’s continued mastery of the law (he knows exactly where the limit is by counting the horse’s paces) while simultaneously highlighting his spiritual alienation.7

- Intertextuality and Redaction: Rubenstein notes that the Bavli’s version is significantly expanded from the Yerushalmi’s. The Bavli adds the motif of the “heavenly voice” (Bat Kol) declaring “Return o backsliding children—except for Aher”.7 This addition transforms a story about simple apostasy into a theological tragedy about determinism. Is Aher’s refusal to repent an act of free will, or is he cosmically rejected? The Stam leaves this ambiguity unresolved, creating a “tragic” mode rare in earlier Rabbinic literature.

- The Poetics of the Voice: The introduction of the Bat Kol creates a vertical axis (Heaven vs. Earth) that intersects with the horizontal axis of the journey. This intersection of planes is a common poetic device in Bavli narratives to signify moments of crisis.7

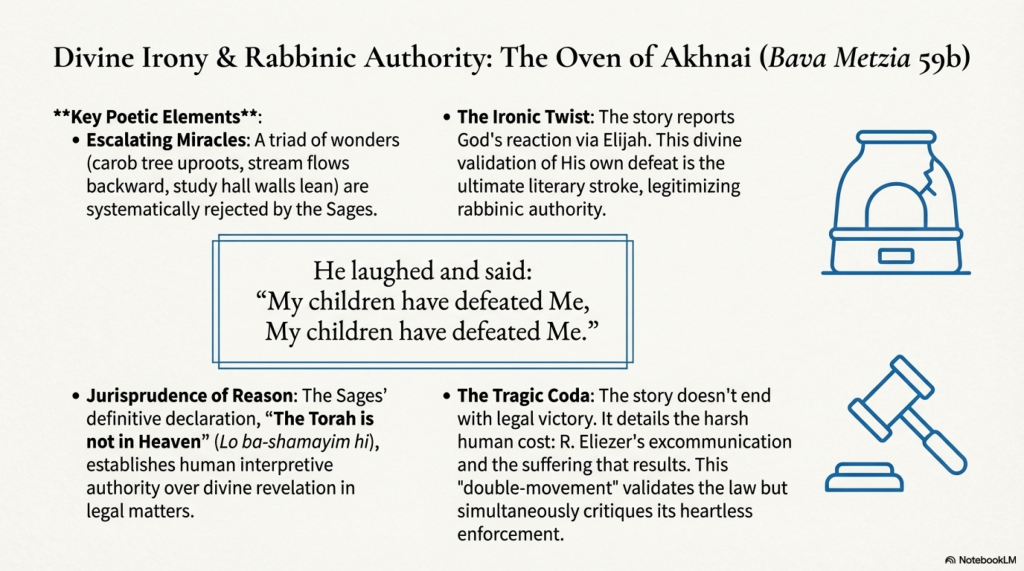

3.2 The Oven of Akhnai: Polyphony, Authority, and Irony

The story of the Oven of Akhnai (Bava Metzia 59b) is perhaps the most analyzed narrative regarding Rabbinic authority. It depicts Rabbi Eliezer utilizing miracles to prove his legal ruling regarding the purity of an oven, only to be overruled by the majority who declare “The Torah is not in Heaven”.23

- The Poetics of Miracles: The miracles are structured in an escalating triad (Carob tree uproots >>> Stream flows backward >>> Walls of the study house lean). The refusal of the Sages to accept these signs establishes a “jurisprudence of reason” over a “jurisprudence of revelation”.24

- Divine Irony and Anthropomorphism: The story culminates in Elijah the Prophet reporting that God “laughed and said: My children have defeated Me.” This anthropomorphic depiction of God validating His own defeat is a supreme literary stroke. It legitimizes human interpretative authority through the very divine voice it claims to ignore.23

- The Cost of Truth: The narrative does not end with the legal victory. It continues to describe the excommunication of Rabbi Eliezer and the subsequent death of Rabban Gamliel caused by Eliezer’s grief. The poetics here shift from legal triumphalism to tragic consequence. The text emphasizes onaat devarim (verbal oppression), suggesting that while the Sages were legally right, their enforcement of conformity caused cosmic destruction.23 This “double-movement”—validating the law but condemning the enforcement—is characteristic of the Bavli’s complex moral vision.

3.3 Folklore and Fantasy: The Tales of Rabbah bar bar Hama

The Bavli contains a unique corpus of “tall tales” attributed to Rabbah bar bar Hama (Bava Batra 73b-74a), describing giant beasts, the leviathan, and fantastic voyages.

- Genre Bending: These stories defy the standard realism of Rabbinic narrative. They function as Menippean satire or folklore, utilizing exaggeration to explore the limits of human knowledge and the mysteries of creation.7

- Literary Context: While often dismissed as mere folklore, literary analysis reveals that these tales are carefully integrated into discussions about the messianic age and the interpretation of scripture. They serve as “aggadic hyperboles” that parallel the legal hyperboles found elsewhere in the Talmud.7

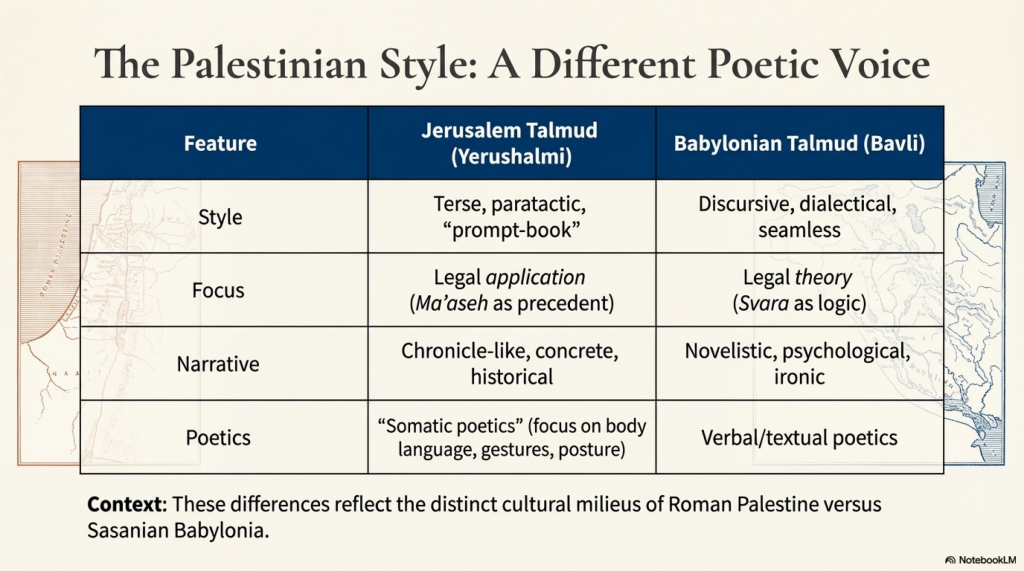

4. The Distinct Poetics of the Jerusalem Talmud (Yerushalmi)

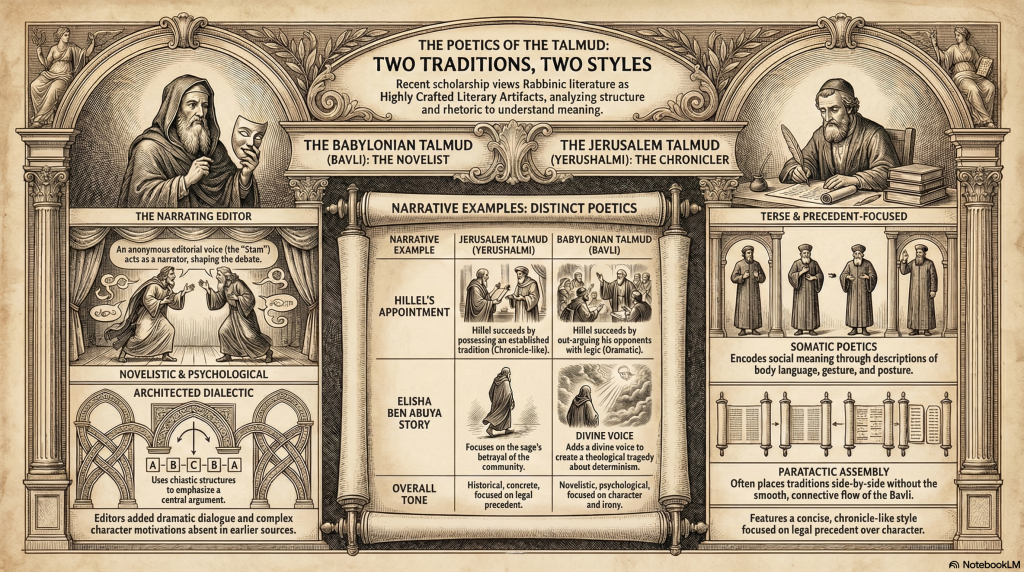

The Yerushalmi is often described as “terse,” “unfinished,” or “choppy” compared to the Bavli.27 However, recent scholarship by Catherine Hezser and others suggests that the Yerushalmi possesses its own distinct poetics and narrative logic, reflecting the intellectual culture of Roman Palestine.

4.1 Stylistic Minimalism and the “Prompt Book”

The Yerushalmi’s conciseness is not necessarily a defect but a stylistic choice. It often presents legal discussions in a shorthand format, assuming the reader’s familiarity with the arguments. This has led some to view it as a “prompt book” or a set of lecture notes rather than a fully redacted literary work like the Bavli.27

However, the Yerushalmi does employ structural patterns. It often utilizes a repetitive, rhythmic structure to link disparate cases. For example, the repetition of specific introductory phrases in Yerushalmi Nezikin creates a “rhetoric of linkage” that binds the legal cases together.13 Unlike the Bavli, which strives for a seamless dialectical flow (Shakla v’Tarya), the Yerushalmi is often paratactic, placing traditions side-by-side without explicit connective tissue.

4.2 Narrative Differences: Synoptic Analysis

A synoptic comparison of parallel stories in the Bavli and Yerushalmi illuminates the distinct poetics of each Talmud.

Table 2: Synoptic Comparison of Yerushalmi and Bavli Narrative Poetics

| Narrative Element | Jerusalem Talmud (Yerushalmi) | Babylonian Talmud (Bavli) |

|---|---|---|

| Hillel’s Appointment | Focus: Transmission and Lineage. Hillel succeeds because he possesses the tradition from Shemaiah and Avtalyon. Style is “chronicle-like.” 30 | Focus: Dialectic Superiority. Hillel succeeds because he out-argues the Bnei Betera using Babylonian logic. Includes dramatic rebuke for arrogance. 30 |

| Rav Sheshet/Judah | Focus: Physical suffering as atonement. Concise description of the affliction. 31 | Focus: The theology of suffering. Expanded dialogue about the merit of suffering and the refusal of divine comfort. 31 |

| Elisha ben Abuyah | No Bat Kol (Heavenly Voice) rejecting him. Focus is on his betrayal of the community. 7 | Adds the Bat Kol. Focus shifts to the theological paradox of determinism and the tragedy of the rejected soul. 7 |

| Tone | Historical, concrete, focused on Ma’aseh (precedent). | Novelistic, psychological, focused on character and irony. |

4.3 Hezser’s Analysis: The “Case Story” and Body Language

Catherine Hezser’s analysis of the “Form and Function of the Rabbinic Story in Yerushalmi Neziqin” argues that Yerushalmi stories are often collections of “case stories” that serve as legal precedents.29 Unlike the Bavli, which weaves stories into the dialectical flow to explore legal theory, the Yerushalmi often presents them in blocks to demonstrate legal application.

Furthermore, Hezser identifies a poetics of “Body Language” in the Yerushalmi. The text frequently encodes social hierarchy and rabbinic identity through descriptions of gestures, posture, and spatial arrangement, serving as a non-verbal communication system within the text.33 This “somatic poetics” is more pronounced in the Palestinian tradition, reflecting the visual culture of the Greco-Roman world, whereas the Bavli is more focused on the verbal/textual world.

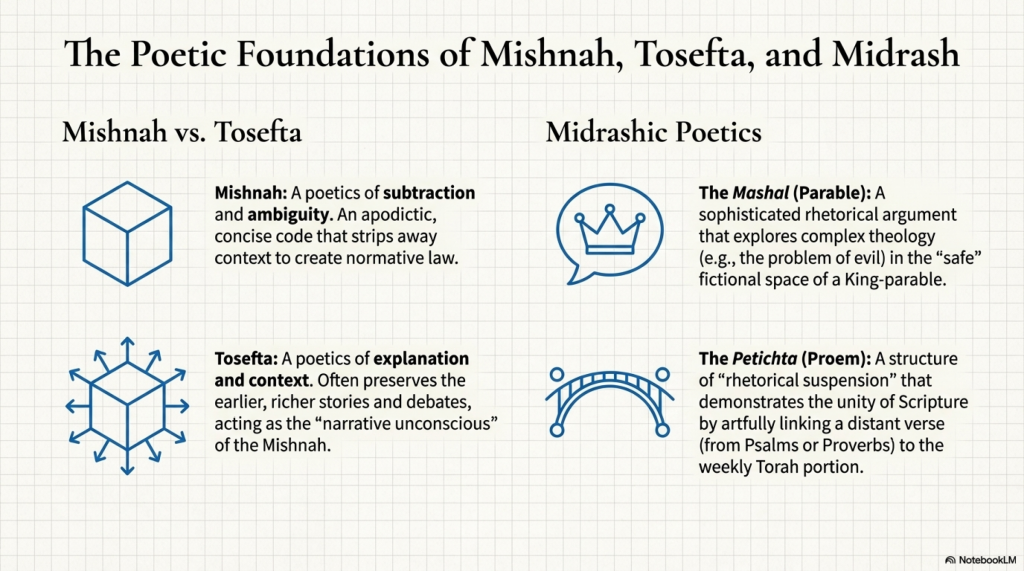

5. Poetics of the Cognates: Mishnah, Tosefta, and Midrash

To fully understand Talmudic poetics, one must examine the cognate literatures that form its substrate and context.

5.1 The Mishnah vs. The Tosefta: Brevity and Verbosity

The relationship between the Mishnah and the Tosefta is a subject of intense scholarly debate that has profound poetic implications.

- The Standard View: The Mishnah is the primary code, and the Tosefta (“Supplement”) is a later commentary.

- The Friedman-Hauptman Theory: Much of the Tosefta preserves an earlier stratum (a “Proto-Mishnah”) which the Mishnah edited and condensed.35

From a poetic standpoint, if the Tosefta is the source, then the Mishnah’s poetics are defined by subtraction. Rabbi Judah the Prince (the Mishnah’s redactor) created a “poetics of ambiguity” by stripping away the context, reasoning, and minority opinions found in the Tosefta.35

Table 3: Poetic Contrast Between Mishnah and Tosefta

| Feature | Mishnah (The Code) | Tosefta (The Supplement/Source) |

|---|---|---|

| Style | Apodictic, concise, rhythmic. Uses mnemonic patterns (lists, numbers). | Discursive, explanatory, verbose. |

| Narrative | Sparse; narrative serves strictly to establish legal precedent (Ma’aseh). | Richer in context; describes emotions and motivations (e.g., Hannah “speaking in her heart”). 38 |

| Voice | Authoritative, often anonymous. “The Sages say…” | Varied; preserves the raw “give-and-take” and individual attributions. |

| Function | Memorization and Normativity. | Explanation and Documentation. |

Wimpfheimer notes that the Tosefta often serves as the “narrative unconscious” of the Mishnah, preserving the messy stories of legal formation that the Mishnah suppresses to create a seamless code.21

5.2 Midrashic Poetics: The Mashal and the Petichta

The Midrash (homiletic and exegetical literature) operates with a distinct set of poetic devices designed to bridge the gap between the biblical text and the contemporary audience.

5.2.1 The Poetics of the Mashal (Parable)

The Mashal is the most distinctive narrative form in Midrash. David Stern’s definitive work, Parables in Midrash, analyzes the Mashal not just as a folk tale but as a sophisticated rhetorical argument.39

- Structure: A standard Mashal consists of the Mashal proper (the story, often about a King), the Nimshal (the application to the biblical verse/God/Israel), and the nexus point (usually a lemma or prooftext).40

- The King-Mashal: The ubiquitous figure of the “King” in parables serves as a theological cipher for God. Stern argues that this anthropomorphism allows the Rabbis to explore complex theological problems—such as God’s apparent abandonment of Israel or the problem of evil—within the “safe” space of fiction.41

- The Hermeneutic Gap: The poetics of the Mashal rely on the friction between the story and its application. The Mashal is never a perfect allegory; there is always a “surplus of meaning” or a gap that the audience must fill.40 For instance, in the Midrash of the “Passerby and the Fortress” (explaining Abraham’s discovery of God), the ambiguity of whether the fortress is “burning” (a world in chaos) or “illuminated” (a world of order) forces the reader to actively participate in the theological construction.42

5.2.2 The Petichta (Proem): The Art of Opening

The Petichta is a formal homiletic structure found in Midrashim like Leviticus Rabbah and Pesiqta de-Rav Kahana. Its poetic function is “stringing beads” (chariza)—linking a verse from the Hagiographa (usually Psalms or Proverbs) to the weekly Torah portion.43

- Rhetorical Suspension: The Petichta begins far away from the topic, creating suspense. The preacher moves through a series of verbal associations and puns, “opening” the distant verse until it inevitably lands on the first verse of the Torah reading.44

- The Unity of Scripture: This structure demonstrates the unity of Scripture. By connecting the “distant” Writings with the “central” Torah, the Darshan (preacher) performs a poetic act of unification, showing that all of Torah speaks with one voice.42

5.2.3 Ring Composition in Leviticus Rabbah

Leviticus Rabbah is unique among Midrashic collections for its high degree of literary structuring. Unlike earlier verse-by-verse commentaries (like Sifra), Leviticus Rabbah is organized into thematic homilies. Scholars have identified Ring Composition (concentric structure) within these homilies and even across the book of Leviticus itself.46

- The Pattern: A-B-C-B’-A’.

- The “Torah Weave”: The structure of Leviticus (and its Midrashic treatment) often places the concept of “Holiness” at the physical center (Ch. 19), with laws of sacrifice and purity radiating outwards symmetrically.46 This literary structure mirrors the architecture of the Tabernacle itself (moving from the outer court to the Holy of Holies), suggesting that the text is constructed as a temple.48

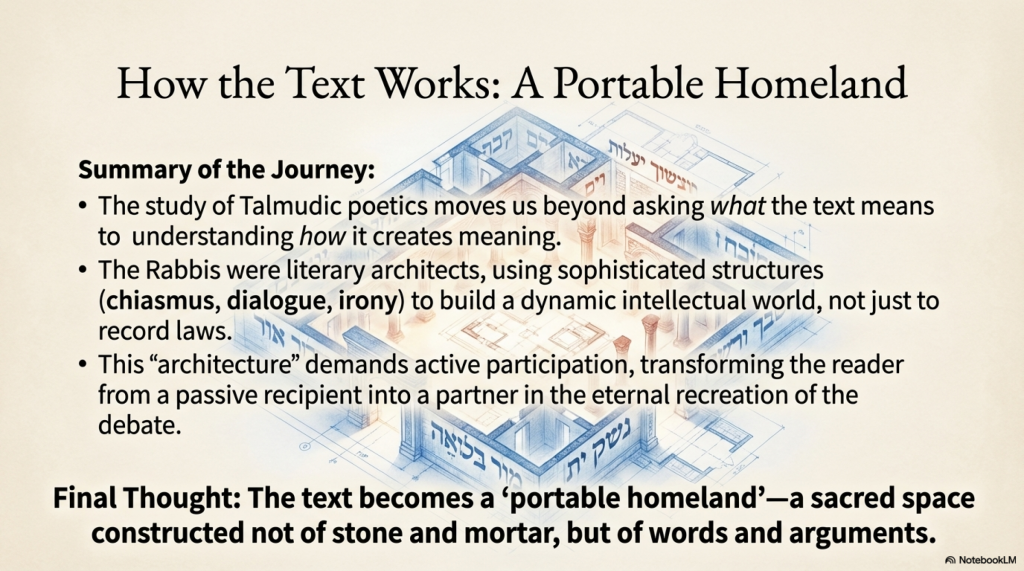

6. Conclusion: The Portable Homeland

The poetics of the Talmuds and their cognates reveal a literature of immense complexity and self-awareness. Far from being a chaotic accumulation of traditions, these texts exhibit sophisticated architectural designs—from the micro-structure of the chiastic sugya to the macro-structure of the Midrashic homily.

The divergence between the Bavli and Yerushalmi highlights two distinct literary cultures: the Bavli’s dialectical, novelistic, and highly redacted style versus the Yerushalmi’s terse, anthological, and precedent-focused style. This reflects the different cultural milieus of Sasanian Babylonia, with its emphasis on academic abstraction, versus Roman Palestine, with its emphasis on tradition and case law.5

The Tosefta and Midrash further expand this poetic universe, offering alternative modes of legal and theological expression. The Mashal allows for theological daring through fiction, while the Tosefta preserves the narrative context that the Mishnah suppresses.

Ultimately, the study of Talmudic poetics moves beyond the question of “what the text means” (exegesis) or “what happened” (history) to the question of “how the text works” (poetics). It uncovers the mechanisms by which the Rabbinic sages transformed oral debate into a timeless textual “home.” By utilizing structures like chiasmus, ring composition, and the dialogic sugya, the Rabbis created a text that demands active participation from its reader—a “pedagogy of reading” that ensures the continuity of the tradition not just through obedience to the law, but through the eternal recreation of the debate.12

Works cited

- Introduction: The Talmud, Rabbinic Literature, and Jewish Culture – Cambridge Core – Journals & Books Online, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://resolve.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/20E3330F3077CB4AF514880145B83DC0/9781139001519int_p1-14_CBO.pdf/introduction_the_talmud_rabbinic_literature_and_jewish_culture.pdf

- Narrative in the Talmud – Jewish Studies – Oxford Bibliographies, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/abstract/document/obo-9780199840731/obo-9780199840731-0116.xml

- (PDF) Talmud as Novel – ResearchGate, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332138455_Talmud_as_Novel

- Rabbinic literature – Wikipedia, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabbinic_literature

- Rabbinic Literature – Jewish Studies – Oxford Bibliographies, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/abstract/document/obo-9780199840731/obo-9780199840731-0019.xml

- ORAL TRADITION 14.1 – Complete Issue, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://journal.oraltradition.org/wp-content/uploads/files/articles/14i/14_1_complete.pdf

- Elements of a Literary Approach to the Rabbinic Narrative – NYU Arts & Science, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://as.nyu.edu/content/dam/nyu-as/faculty/documents/RubensteinContextGenre.pdf

- Talmudic Stories, Then and Now: A Retrospective by Jeffrey Rubenstein, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.ancientjewreview.com/read/2016/2/9/talmudicstories

- Repurposing the Building Materials of the Religious Academy – H-Net Reviews, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=41787

- The Talmud as a fat Rabbi: A novel approach – ResearchGate, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250975728_The_Talmud_as_a_fat_Rabbi_A_novel_approach

- Literary construction in the Babylonian Talmud: a case-study from Perek Helek – CORE, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://core.ac.uk/download/33527657.pdf

- The Poetic Superstructure of the Babylonian Talmud and the Reader It Fashions – eScholarship, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://escholarship.org/content/qt5bx332x5/qt5bx332x5.pdf

- Some Structural Patterns of Yerushalmi Sugyot, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://as.nyu.edu/content/dam/nyu-as/faculty/documents/StructuralPatternsYerushalmiSugyot.pdf

- Chiastic Structure – onthewing.org, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.onthewing.org/user/BS_Chiastic%20structure.pdf

- Chiastic structure – Wikipedia, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chiastic_structure

- Chiasmus In Writing or The Chiastic Structure – Learn How To Write A Novel, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://learnhowtowriteanovel.com/blog/2019/01/10/chiasmus-in-writing-or-the-chiastic-structure/

- Abstract Metasystemic and Structural Indicators of Late-Stage Babylonian Stammaitic Compositions – Oqimta, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.oqimta.org.il/oqimta/5773/eng-abst-rovner1.pdf

- The Tripartite Structure of General Halachic Principles in the Bavli – MDPI, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/8/12/262

- Berakhot 19b: The Bavli’s Paradigm of Confrontational Discourse – W\&M ScholarWorks, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://scholarworks.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1092\&context=jtr

- Narrating the Law: A Poetics of Talmudic Legal Stories – Jewish Book Council, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.jewishbookcouncil.org/book/narrating-the-law-a-poetics-of-talmudic-legal-stories

- Narrating the Law: A Poetics of Talmudic Legal Stories by Barry Scott Wimpfheimer (review), accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265696951_Narrating_the_Law_A_Poetics_of_Talmudic_Legal_Stories_by_Barry_Scott_Wimpfheimer_review

- Barry Scott Wimpfheimer. Narrating the Law: A Poetics of Talmudic Legal Stories. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. 248 pp. | AJS Review, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ajs-review/article/barry-scott-wimpfheimer-narrating-the-law-a-poetics-of-talmudic-legal-stories-philadelphia-university-of-pennsylvania-press-2011-248-pp/E54E72F98767FF5C547C4911289A06FB

- The Rabbis, the oven and the ostracism | Dan Ornstein – The Blogs – The Times of Israel, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-rabbis-the-oven-and-the-ostracism/

- Rereading the Story of the Oven of Akhnai: From Interpretive Rights to Interpretive Responsibilities – Sources Journal, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.sourcesjournal.org/articles/rereading-the-story-of-the-oven-of-akhnai-from-interpretive-rights-to-interpretive-responsibilities

- The Oven of Akhnai, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://npgovernance.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/the-oven-of-akhnai.pdf

- God is Dead!…or is He? (Oven of Akhnai pt2) – David Leon, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://davidleon.blog/2024/01/05/god-is-dead-or-is-he-oven-of-akhnai-pt2/

- The Editing of the Talmud | My Jewish Learning, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-editing-of-the-talmud/

- Tale of Two Talmuds: Jerusalem and Babylonian | My Jewish Learning, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/tale-of-two-talmuds/

- Rabbinic Scholarship in the Context of Late Antique Scholasticism: The Development of the Talmud Yerushalmi 1350420980, 9781350420984 – DOKUMEN.PUB, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://dokumen.pub/rabbinic-scholarship-in-the-context-of-late-antique-scholasticism-the-development-of-the-talmud-yerushalmi-1350420980-9781350420984.html

- Hillel and Shammai Revisited – Brill, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004352056/BP000017.pdf

- (PDF) The delicacy of the rabbinic asthenes – ResearchGate, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342688407_The_delicacy_of_the_rabbinic_asthenes/download

- The formation and character of the Jerusalem Talmud | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292362159_The_formation_and_character_of_the_Jerusalem_Talmud

- H-Net Reviews, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=51384

- Professor Catherine Hezser – SOAS, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.soas.ac.uk/about/catherine-hezser

- Mishnah and Tosefta | My Jewish Learning, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/mishnah-tosefta/

- 63-the-primacy-of-tosefta-to-mishnah-in-synoptic-parallels.pdf – Prof. Shamma Friedman, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://shammafriedman.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/63-the-primacy-of-tosefta-to-mishnah-in-synoptic-parallels.pdf

- THE TOSEFTA AS A COMMENTARY ON AN EARLY MISHNAH, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://jewish-faculty.biu.ac.il/files/jewish-faculty/shared/JSIJ4/hauptman.pdf

- Poetry – Scattered Leaves, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://scatteredleaves.net/category/poetry/

- Parables in Midrash – Harvard University Press, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674654488

- Better Parables, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.betterparables.com/parables

- Parables in Midrash : narrative and exegesis in rabbinic literature – Stanford SearchWorks, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/1970707

- Learning to Read Midrash, Chapter 3; The Petihta; Using a Verse to Interpret a Verse; The Passerby and the Fortress – Sefaria, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.sefaria.org/Learning_to_Read_Midrash,_Chapter_3;_The_Petihta;_Using_a_Verse_to_Interpret_a_Verse;_The_Passerby_and_the_Fortress

- “To Bloom in Empty Space”: An Introduction and Commentary on the Petichta to Esther Rabbah, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019\&context=reli_honors

- The Inner Workings of a Genizah Midrash on the Symbolic Value of Orlah – TheTorah.com, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.thetorah.com/article/the-inner-workings-of-a-genizah-midrash-on-the-symbolic-value-of-orlah

- Structure and Editing in the Homiletic Midrashim | AJS Review | Cambridge Core, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ajs-review/article/structure-and-editing-in-the-homiletic-midrashim/A4819D3585D8709D742A6A5F875D4C57

- Literary Structural Map of Leviticus – woven-torah, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://woven-torah.com/leviticus-map/

- structure Is theology: the Composition of leviticus – Chaver.com, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://chaver.com/Torah/Structure%20is%20Theology%20Published%20Version.pdf

- #183 – Leviticus and Ring Composition – Buzzsprout, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.buzzsprout.com/1306753/episodes/14648436-183-leviticus-and-ring-composition

- 289) HOW ‘STUDY’ AND THE ‘STUDY-HOUSE’ ARE DEPICTED DIFFERENTLY IN THE BAVLI AND YERUSHALMI – Kotzk Blog, accessed on December 10, 2025, https://www.kotzkblog.com/2020/08/289-how-study-and-study-house-are.html