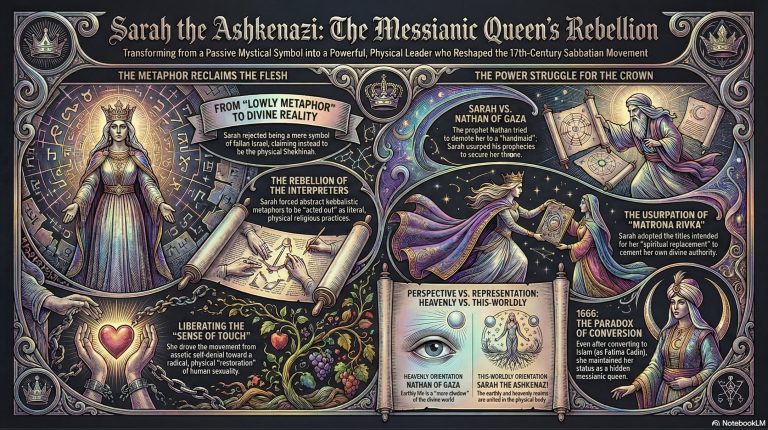

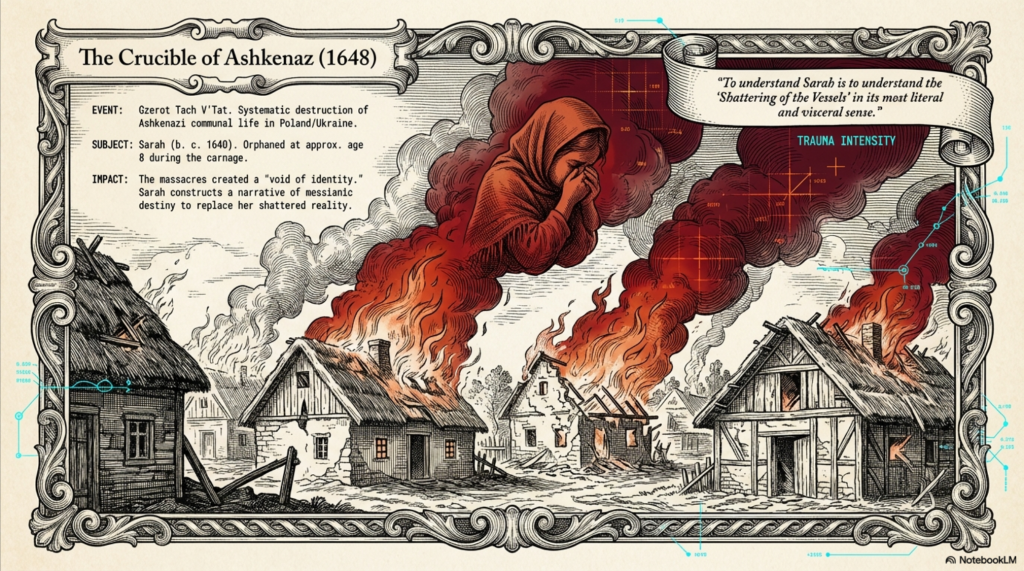

The seventeenth century in Jewish history remains a period of profound ontological instability, characterized by a transition from the medieval structure of the ghetto to the early modern fragmentation of the messianic impulse. At the center of this psychic storm stands Sarah the Ashkenazi, a figure whose life and legacy represent a radical convergence of individual trauma and collective eschatology. Often relegated to the periphery of her husband’s messianic drama, Sarah emerges upon closer psychohistorical inspection as the true pivot of the Sabbatian movement’s transgressive energy. To understand Sarah is to understand the “Shattering of the Vessels” in its most literal and visceral sense: her life began in the wreckage of the 1648 Khmelnytsky massacres and culminated in an Albanian exile, mapping a trajectory of displacement that mirrored the exiled Shekhinah herself.1

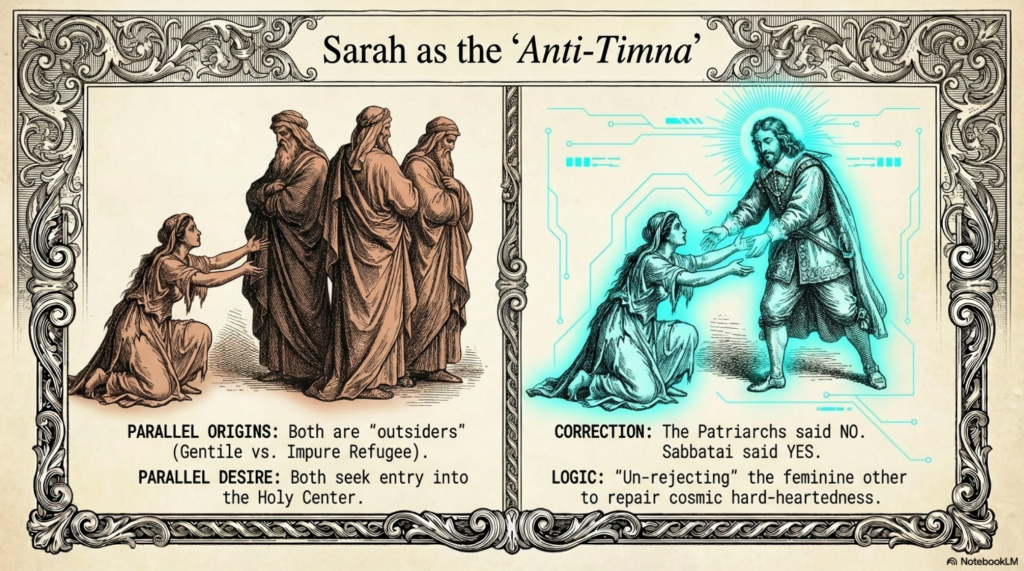

By integrating the theological innovations of Nathan of Gaza and the psychological volatility of Sabbatai Tzvi with the biblical archetype of Timna, this report explores the mechanism by which a traumatized refugee was transformed into a “Messianic Queen.” The comparison between Sarah and Timna is not merely academic; it is a structural necessity for understanding the “Kabbalah of the Feminine.” While Timna represents the “rejected outsider” whose exclusion by the Patriarchs birthed the existential threat of Amalek, Sarah represents the “integrated outsider” whose acceptance by the Messiah signaled a catastrophic attempt to rectify the cosmic hierarchy.4 This analysis seeks to demonstrate that Sarah’s agency was not derivative but foundational, serving as the “this-worldly” anchor for a movement that sought to collapse the distance between the divine metaphor and human flesh.7

The Crucible of Ashkenaz: Trauma and the Genealogy of a Prophetess

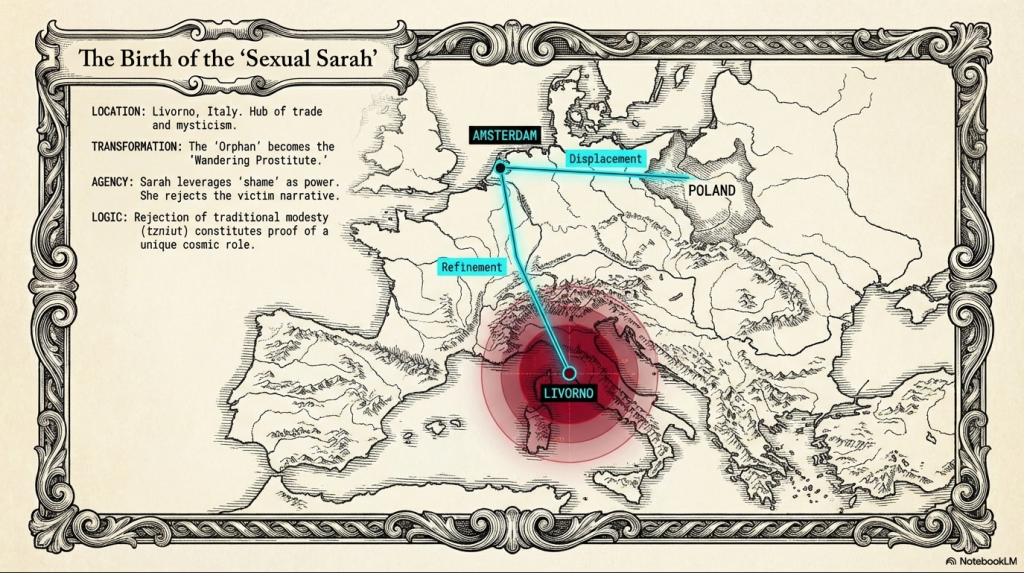

The psychohistorical origins of Sarah the Ashkenazi are rooted in the catastrophic violence of the 1648 Khmelnytsky uprising in Poland and Ukraine. This period, known in Jewish history as Gzerot Tach V’Tat, resulted in the systematic destruction of Ashkenazi communal life and the displacement of tens of thousands of survivors.1 Sarah, born approximately in 1640, was orphaned during these massacres, a fact that historians emphasize as the “primary trauma” of her messianic identity.1 From a psychological perspective, the loss of her family and homeland created a “void of identity” that she would later fill with a self-constructed narrative of messianic destiny.

Following the massacres, Sarah’s path led her through Northern Europe to Amsterdam and eventually to the Mediterranean hub of Livorno, Italy. It was in Livorno that the “birth of a sexual Sarah” occurred.2 The labels applied to her during this period—”prostitute,” “debaucherous,” and “wandering”—must be viewed through the lens of a refugee’s survival in a patriarchal world that offered few roles for unattached women. However, Sarah did not merely survive; she mythologized her own transgression. She became convinced, and expressed with “brash and public” intensity, that she was destined to marry the Messiah.8 This conviction represents a profound act of psychological agency. Rather than accepting the status of a victimized orphan, Sarah leveraged her “outsider” status as a prophetic credential, asserting that the traditional laws of modesty no longer applied to her because of her unique cosmic role.7

Comparative Regional Impacts on Messianic Development

| Geographic Context | Historical Influence | Psychohistorical Impact on Sarah |

|---|---|---|

| Poland/Ashkenaz | 1648 Khmelnytsky Massacres | Formation of the “orphan” identity; source of radical displacement trauma.1 |

| Livorno, Italy | Cosmopolitan trade; mystical subcultures | Development of the “sexual” persona; exposure to “this-worldly” orientations.2 |

| Cairo, Egypt | Center of Sephardic and Mizrahi power | Integration into the messianic court of Raphael Joseph Chelebi.1 |

| Istanbul/Gaza | Political heart of the Ottoman Empire | Transformation from refugee to Queen; public prophetic role.2 |

The designation of “Sarah the Pole” or “Sarah the Ashkenazi” served as a persistent marker of her “otherness” within the predominantly Sephardic leadership of the Sabbatian movement. This ethnic and cultural friction is significant; Sarah brought the “brokenness” of the Northern European experience into the Mediterranean theater of redemption. The shattered vessels of the Polish ghettos were to be repaired, she believed, through her union with the Messiah of the South.1

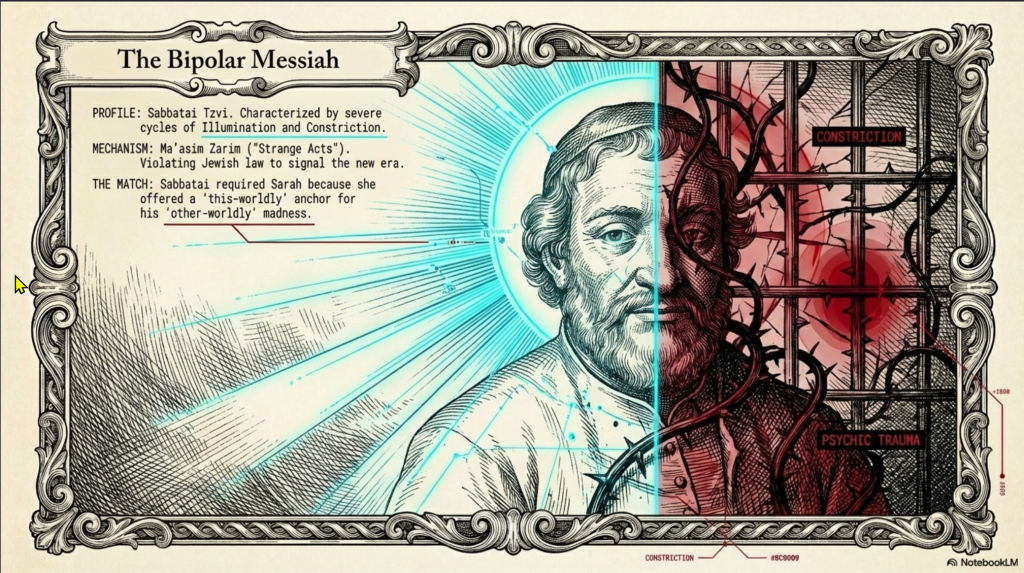

The Union of Bipolarities: Sabbatai Tzvi and the Messianic Court

When news of Sarah’s beauty and her strange claims reached Sabbatai Tzvi in Cairo, he recognized a psychological and theological counterpart. Sabbatai Tzvi was a figure of extreme mental volatility, characterized by modern scholars as possessing a bipolar or manic-depressive personality.1 His life was defined by cycles of “illumination” (manic phases) and “constriction” (depressive phases). During his illuminations, he performed “strange acts” (ma’asim zarim)—public violations of Jewish law intended to signal the arrival of a new, antinomian era.7

The marriage of Sabbatai and Sarah (c. 1664) was perhaps the most significant of these strange acts. Prior to Sarah, Sabbatai had married and divorced two women because he was unable or unwilling to consummate the unions within the traditional domestic framework. His marriage to Sarah was different; it was demonstratively sexual and public, serving as a symbolic marriage between the Messiah and the “fallen” Shekhinah.7 In the Sabbatian imagination, Sarah’s history as a “prostitute” was not a moral stain but a mystical necessity. She was the “Holy Harlot” (Zonah Kedoshah) who had descended into the kelipot (husks) to retrieve the sparks of holiness that could only be reached through transgression.2

The Dynamics of the Messianic Marriage

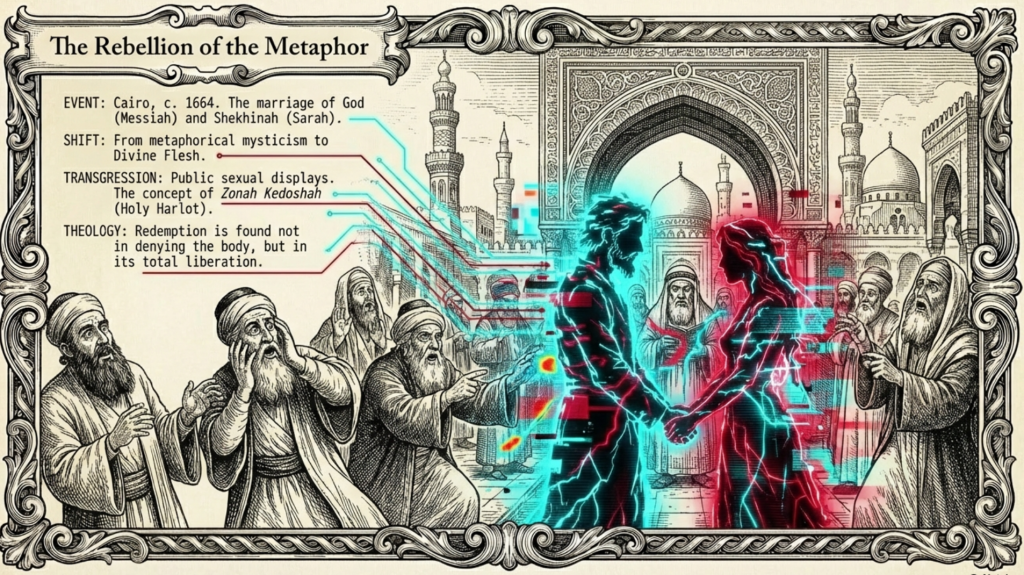

The relationship between Sabbatai and Sarah created a new “messianic court” where the traditional boundaries of gender and propriety were abolished. Sarah was not merely a consort; she was a prophetess who occupied a prominent position of power.7 She was allowed to have men in her room, and the couple openly engaged in sexual activities that challenged the very foundations of Jewish modesty (tzniut).7 This behavior was justified through a “realistic and nonmetaphorical” interpretation of Kabbalah. While medieval mystics saw erotic descriptions in religious texts as guides for internal meditation, Sarah and Sabbatai insisted that these processes were happening in the flesh, in “divine flesh”.7

This shift represented a “rebellion of the metaphor.” Sarah refused to be a “lowly metaphor” for the divine feminine; she claimed to be the divine feminine in the physical world.7 This “this-worldly” attitude was a radical departure from the asceticism of previous mystical traditions. By locating the Shekhinah in Sarah’s sexual body, the movement collapsed the hierarchy between the heavenly and the earthly, suggesting that redemption was to be found not in the denial of the body, but in its total liberation.2

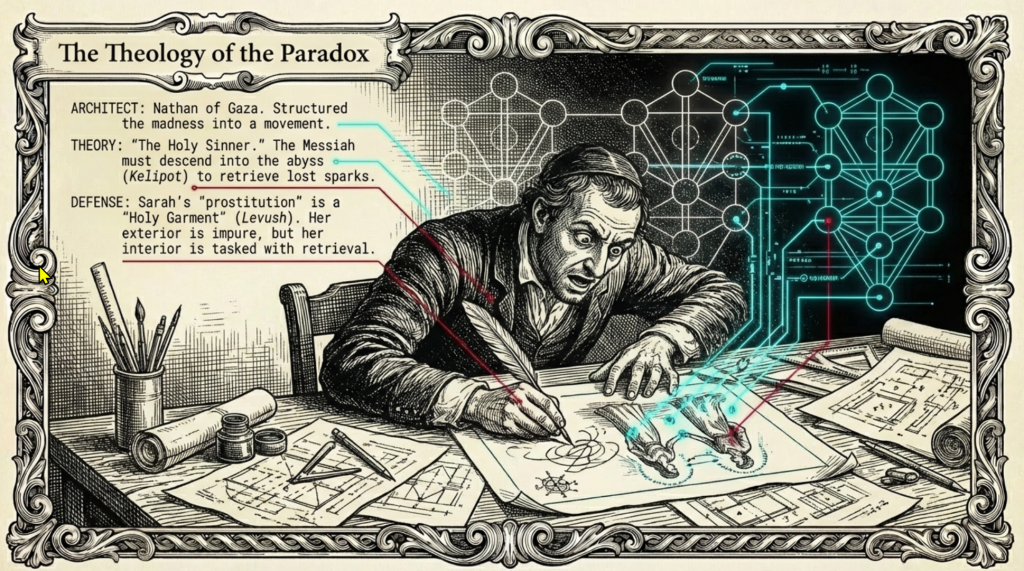

Nathan of Gaza: The Prophet of the Paradox

If Sarah provided the “this-worldly” anchor and Sabbatai the manic energy, Nathan of Gaza provided the intellectual and theological structure that made the movement sustainable. Nathan was a brilliant young mystic who recognized Sabbatai as the Messiah and developed a complex system of “heretical Kabbalah” to explain his paradoxical mission.7 Nathan’s primary contribution was the theology of the “Holy Sinner,” which argued that the Messiah must descend into the depths of impurity to battle the forces of evil (Samael and Lilith) and liberate the final sparks of holiness.10

Nathan utilized the concept of the “garment” (levush) to justify the scandalous nature of the messianic couple. He argued that just as the Messiah’s soul could be “clothed” in the “evil garment” of apostasy (his later conversion to Islam), Sarah’s soul was clothed in the garment of a “prostitute”.1 This interior/exterior split was central to Nathan’s defense: the exterior might appear “evil,” but the interior was “holy”.11

Theological Framework of the Sabbatian Movement

| Theological Concept | Definition and Application | Role of Sarah/Nathan |

|---|---|---|

| Holy Sinner | The Messiah must perform transgressive acts to redeem fallen sparks.10 | Justification of Sarah’s “sexual” reputation and transgressive court.2 |

| Hamitsvot Betelot | “The commandments are abolished” in the messianic age.11 | Radical freedom from Halakha; public violations of modesty.7 |

| Zonah Kedoshah | The “Holy Harlot” who retrieves sparks from the abyss.2 | Sarah as the living embodiment of the “fallen” but “holy” Shekhinah.2 |

| Tikunei Zohar | Mystical rectifications of the divine structure.11 | Nathan’s source for explaining Sabbatai’s “strange acts” and Sarah’s role.6 |

Nathan’s role in “orbiting” Sarah was crucial. He framed her as the “heavenly Shekhinah” and justified her prominent position as a prophetess.2 Without Nathan’s theological shield, Sarah’s agency might have been dismissed as mere madness or immorality. Nathan transformed her biography from a tale of tragic displacement into a cosmic epic of redemption. He even compared her to the figure of Esther, who was “hidden” within the palace of a foreign king, suggesting that Sarah’s presence in the messianic court was a similar form of “holy hiding”.11

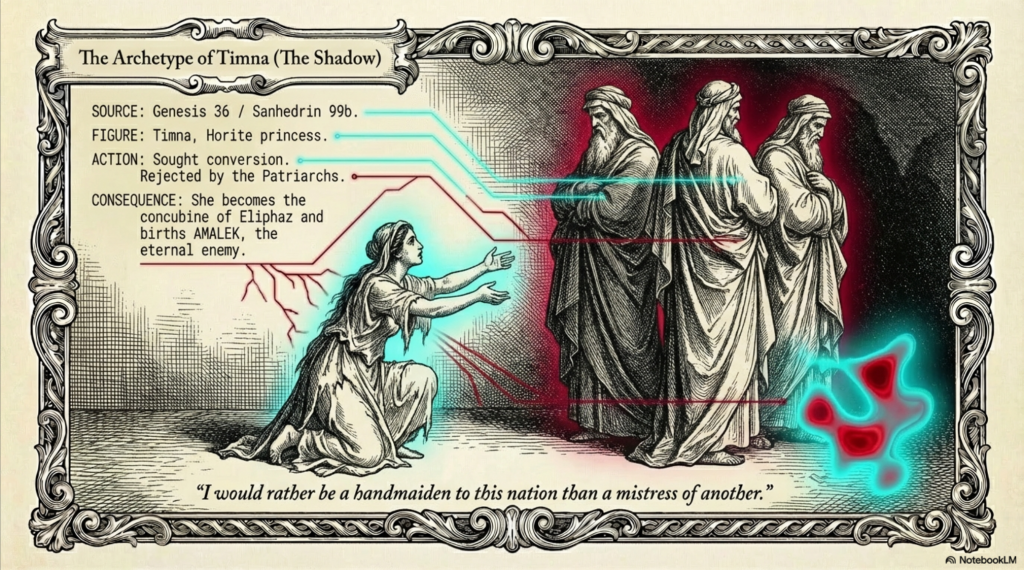

The Archetype of Timna: Rejection and the Birth of Amalek

The psychohistorical resonance of Sarah the Ashkenazi cannot be fully appreciated without a comparison to the biblical figure of Timna. Timna’s story, as expanded in the Midrash and the teachings of the Arizal, serves as the ultimate cautionary tale regarding the “rejected outsider.” According to Genesis 36:12, Timna was the concubine of Eliphaz and the mother of Amalek.4 However, the Talmud (Sanhedrin 99b) reveals a much deeper narrative: Timna was a princess of the Horites who desperately wanted to convert to Judaism.4

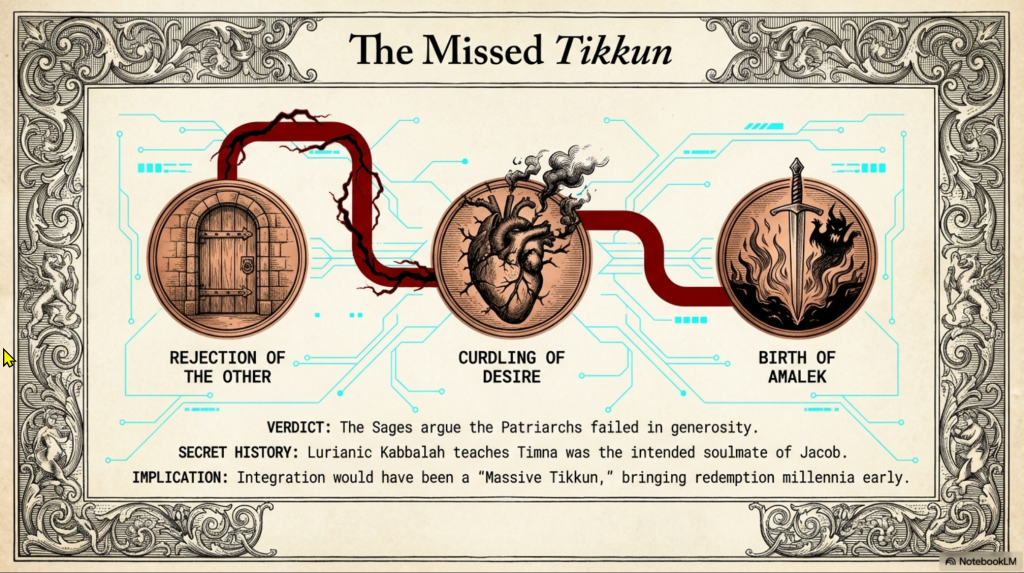

Timna approached the founders of the nation—Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—seeking to join their household. In a moment of collective failure, all three Patriarchs rejected her.4 Her response was an expression of profound desire for the holy: “I would rather be a handmaiden to this nation than a mistress of another nation”.4 Because the Patriarchs “repulsed her,” she turned to Esau’s son, and the result was the birth of Amalek—the nation that would become the archetypal enemy of the Jewish people, preying on the weak and the stragglers.4

The Rejection of the Feminine Other

The Sages emphasize that the birth of Amalek was the direct punishment for the Patriarchs’ lack of generosity and their “anti-gentile convert negativity”.15 From a psychohistorical perspective, the rejection of Timna is the “rejection of the feminine outsider” who carries hidden sparks of holiness. The Arizal takes this further in Sha’ar HaMitzvot, teaching that Timna was actually the intended “soulmate of Jacob”.5 Had Jacob married and converted her, it would have been a “massive tikkun” (rectification) that would have elevated her sparks and potentially brought about the final redemption millennia earlier.6

| Aspect | Timna’s Narrative (The Shadow) | Sarah’s Narrative (The Integration) |

|---|---|---|

| Social Origin | Horite Princess; noble sister of Lotan.13 | Ashkenazi Orphan; refugee of the massacres.1 |

| Initial Desire | To join the house of Israel/Abraham.4 | Conviction that she must marry the Messiah.8 |

| Response of Authority | Rejected by the Patriarchs.4 | Accepted and crowned by Sabbatai Tzvi.2 |

| Psychological Outcome | “Bitter person” seeking to delegitimize the rejecter.12 | Prophetess/Queen seeking to abolish the law.7 |

| Historical Consequence | Birth of Amalek; eternal suffering for Israel.4 | Birth of the Sabbatian paradox; apostasy.8 |

Sarah, in many ways, is the “rectified” Timna. Where the Patriarchs saw only a “gentile” or an “outsider” unworthy of their lineage, Sabbatai Tzvi—a man who himself lived on the margins of sanity and law—saw the “lost soulmate” who had wandered through the kelipot.6 Sarah’s acceptance into the messianic household was a deliberate reversal of the Patriarchal exclusion. By marrying Sarah, Sabbatai was “un-rejecting” the feminine other, a move that Nathan of Gaza framed as a necessary step for the restoration of the cosmic order.

Sarah and the “This-Worldly” Rebellion of the Metaphor

The tension between Sarah and the traditional mystical structure is most evident in her “this-worldly” orientation. Traditional Kabbalah, as practiced by the circle of the Ramak and later the Arizal, often focused on the “hierarchical realms” (yosher) associated with the masculine bestower.9 In this system, the feminine Shekhinah is often portrayed as a passive recipient, a “moon” that reflects the light of the sun but has no agency of its own.18 Sarah the Ashkenazi, however, represented a “turnaround of a long trend”.7

Sarah’s agency was a rebellion against being an “object that served as the metaphor”.7 She did not want to be the “indwelling face of Hashem” as an abstract concept; she wanted to be the Queen of a physical kingdom. This collapse of metaphor back into its object is a central theme of the Sabbatian imagination. It suggested that if the Messiah is here, the “lowly earthly metaphor” is no longer necessary because the divine reality is present in the “female sexual body”.7

The Psychosexual Tikkun

The Arizal taught that every act of holiness retrieves “sparks” trapped in “husks” (kelipot).9 However, Sarah and Sabbatai’s method of retrieval was through “scandalous faith”.11 By engaging in sexual activities that were forbidden by traditional law, they claimed to be “breaking through the shells” of the kelipot from the inside.9 Sarah’s body became the laboratory for this transgressive tikkun. Unlike the ascetic mystics who “directed their erotic drives away from their wives toward… the female element of God,” Sabbatai directed his erotic drive toward Sarah as the literal embodiment of that divine element.7

This had profound psychological implications for the movement’s followers. It offered a “spousal theosis”—a way to experience God through the human body and through the subversion of social norms.2 Sarah was the “earthly queen” who was also the “heavenly Shekhinah,” and her prominence allowed other women in the movement to see themselves as participants in the messianic drama, rather than mere observers.2

Conversion and the Paradox of the “Evil Garment”

The ultimate crisis of the Sabbatian movement occurred in 1666 when Sabbatai Tzvi, faced with execution by the Ottoman Sultan, converted to Islam. He “took the turban,” an act that shocked the Jewish world and led most to believe the movement had failed. However, for the inner circle, this was the ultimate “strange act.” Nathan of Gaza justified it by explaining that the Messiah had to enter the “evil garment” of the dominant religion to liberate the remaining sparks of holiness.11

Sarah followed her husband into conversion, also “donning the turban”.8 For Sarah, this was another layer of displacement—from an Ashkenazi orphan to a Jewish queen to a Muslim convert. Psychohistorically, this mirrors the state of the “Marrano” or “Converso,” but with a messianic twist. The Sabbatians (specifically the Dônmeh branch) lived as “good on the inside” (Jewish/Messianic) while their “garment was evil” (Muslim).11

Sarah as the “Hidden Shekhinah” in the Ottoman Palace

Following the conversion, Sarah and Sabbatai lived in a state of “concealment” within the Ottoman court. Sarah was described as dwelling in the king’s palace and raising her son, Ishmael.11 Some sources claimed her son was a “scholar of great expertise,” a deliberate falsehood intended to suggest that the messianic line was flourishing in secret.11 In reality, the couple was living a life of internal exile, away from the adoring masses of their earlier days.

This period represents the final stage of the Timna/Sarah comparison. Timna, after being rejected, was forced to become a “maidservant” in the house of Esau.13 Sarah, in her conversion, became a “servant” of the Sultan. Both women found themselves in “foreign palaces,” their holiness hidden under layers of external impurity. But where Timna’s exile produced the destructive force of Amalek, Sarah’s exile produced a permanent “restiveness with religious legalism” and a demand for spiritual freedom that would influence Jewish thought for centuries.11

Comparison of Theological Justifications for “The Outsider”

| Figure | Mechanism of “Otherness” | Theological Justification | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timna | Desire to convert to the house of Abraham.4 | “Pure intent” recognized too late by the Sages.13 | Birth of the archetypal enemy, Amalek.4 |

| Sarah (The Pole) | Refugee with a “sexual” reputation.1 | “Zonah Kedoshah” retrieving sparks from the abyss.2 | Transformation of the Shekhinah into “divine flesh”.2 |

| Sabbatai Tzvi | Bipolarity and “strange acts”.1 | “Holy Sinner” mission to descent into the kelipot.10 | Creation of an “apostate” messianic faith.7 |

| Nathan of Gaza | Prophet of a failed/apostate Messiah.7 | The “Garment” theory (exterior vs. interior).11 | Preservation of the movement through “heretical Kabbalah”.10 |

Psychohistory and the Legacy of the “Shattered Queen”

Sarah the Ashkenazi died in approximately 1674, two years before Sabbatai Tzvi’s own “concealment” (death) in Albania.2 Her life remains a testament to the power of the individual to mythologize their own trauma. By refusing to be a victim of the 1648 massacres or a “lowly metaphor” for the divine, she forced a confrontation between the Jewish tradition and its own “rejected” feminine archetypes.

The comparison with Timna reveals that the Sabbatian movement was, at its heart, a reaction against the “hard-heartedness” of the establishment. The Patriarchs’ rejection of Timna created Amalek; the Messiah’s acceptance of Sarah created a movement that sought to “wipe out” the boundaries between the holy and the profane.11 While the movement ultimately led to catastrophe and apostasy, it also signaled the beginning of a “Messianic Feminism”—a realization that the “outsider,” the “orphan,” and the “prostitute” might carry the very sparks needed to repair a shattered world.8

In the psychohistorical narrative, Sarah the Ashkenazi is the “integrated shadow.” She is the Timna who was finally allowed to enter the room, but her entry broke the room itself. The collapse of metaphor into “divine flesh” meant that the old laws could no longer contain the new reality. Sarah’s orbit around Sabbatai Tzvi was not a path of subservience, but a joint trajectory toward a radical, if tragic, form of liberation. She remains the “Heavenly Shekhinah” of a fallen world, a reminder that the most “superfluous” and “boring” passages of history—like the mention of Lotan’s sister Timna—often contain the deepest secrets of creation and the most potent seeds of rebellion.6

The lesson of Timna and Sarah is ultimately one of inclusion: “converts should be welcomed and accepted wholeheartedly,” for they possess the potential for “great holiness”.5 The failure of the Patriarchs to embrace Timna led to centuries of suffering; the radical embrace of Sarah by the Sabbatians led to a revolution of the spirit. Between these two poles—rejection and transgressive integration—the psychohistory of the Jewish people continues to unfold, seeking a middle path where the “outsider” can be brought into the “bosom of Judaism” without shattering the vessels of the law.9

Works cited

- Themes and Trends in Early Modern Jewish Life (Part II) – The …, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-history-of-judaism/themes-and-trends-in-early-modern-jewish-life/E4FF81C1389799C4A33CB458611CA6CB

- From lowly metaphor to divine flesh : Sarah the Ashkenazi, Sabbatai …, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://archive.org/details/fromlowlymetapho0000vand/mode/2up

- Untitled – National Academic Digital Library of Ethiopia, accessed on February 10, 2026, http://ndl.ethernet.edu.et/bitstream/123456789/56351/1/pdf30.pdf

- Amalek – Wikipedia, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amalek

- Timna | Mayim Achronim, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://www.mayimachronim.com/tag/timna/

- Embracing Converts, and the Seeds of Amalek – Mayim Achronim, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://www.mayimachronim.com/embracing-converts-and-the-seeds-of-amalek/

- From Lowly Metaphor To Divine Flesh: Sarah The Ashkenazi, Sabbatai Tsevi’s Messianic Queen and The Sabbatian Movement | PDF | Kabbalah – Scribd, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://www.scribd.com/document/206521430/From-Lowly-Metaphor-to-Divine-Flesh-Sarah-the-Ashkenazi-Sabbatai-Tsevi-s-Messianic-Queen-and-the-Sabbatian-Movement

- Guest Post: The Messianic Feminism of Shabbatai Zevi and Sarah …, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://www.lifeisasacredtext.com/guest-post-the-messianic-feminism/

- Things You Didn’t Know About the Arizal – Bukharian Jewish Link, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://bukharianjewishlink.com/index.php/feature/5768-things-you-didn-t-know-about-the-arizal

- Pomobabble: Postmodern Newspeak and Constitutional “Meaning” for the Uninitiated – University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://repository.law.umich.edu/context/mlr/article/1817/viewcontent/uc.pdf

- Sabbatai Zevi : Testimonies to a Fallen Messiah 9781904113256 …, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://dokumen.pub/sabbatai-zevi-testimonies-to-a-fallen-messiah-9781904113256-1904113257-9781906764241-1906764247.html

- Timna and Amalek: The Rejects – Aish.com, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://aish.com/284299261/

- Timna, concubine of Eliphaz: Midrash and Aggadah | Jewish Women’s Archive, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/timna-concubine-of-eliphaz-midrash-and-aggadah

- A Lesson From Timna the Concubine – Vayishlach – Chabad.org, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://www.chabad.org/theJewishWoman/article_cdo/aid/669550/jewish/A-Lesson-From-Timna-the-Concubine.htm

- Somewhere, there is a Timna | Leora Kling Perkins | The Times of Israel – The Blogs, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/somewhere-there-is-a-timna/

- What should Jews learn from the Goyim in Genesis 36 | Allen S. Maller – The Blogs, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/what-should-jews-learn-from-the-goyim-in-genesis-36/

- Esau | Mayim Achronim | Page 9, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://www.mayimachronim.com/tag/esau/page/9/

- Sarah Yehudit Schneider: ‘Jewish mysticism is not so different from any mysticism’ – 18Forty, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://18forty.org/podcast/sarah-yehudit-schneider-mysticism/

- December | 2016 – Mayim Achronim, accessed on February 10, 2026, https://www.mayimachronim.com/2016/12/