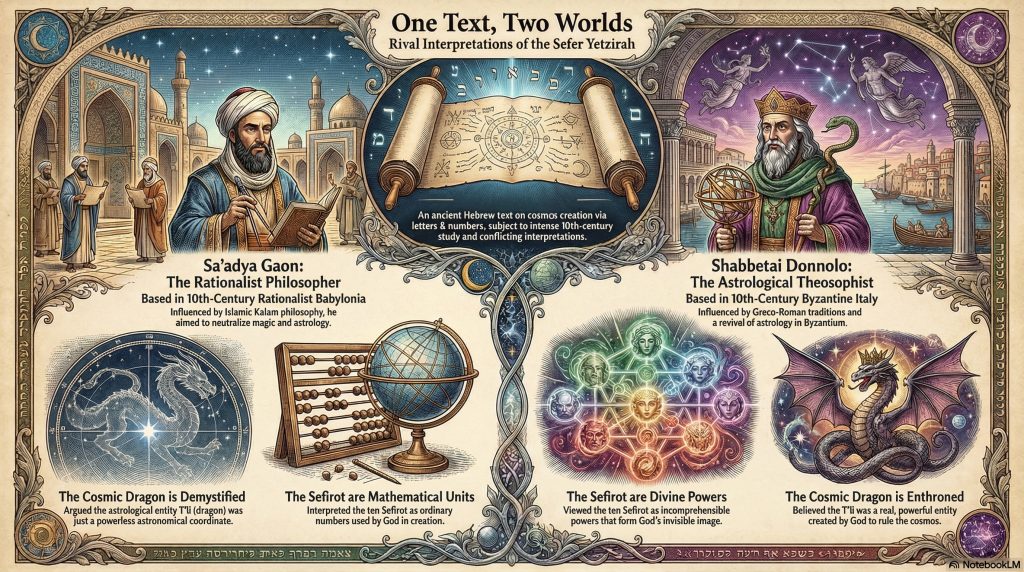

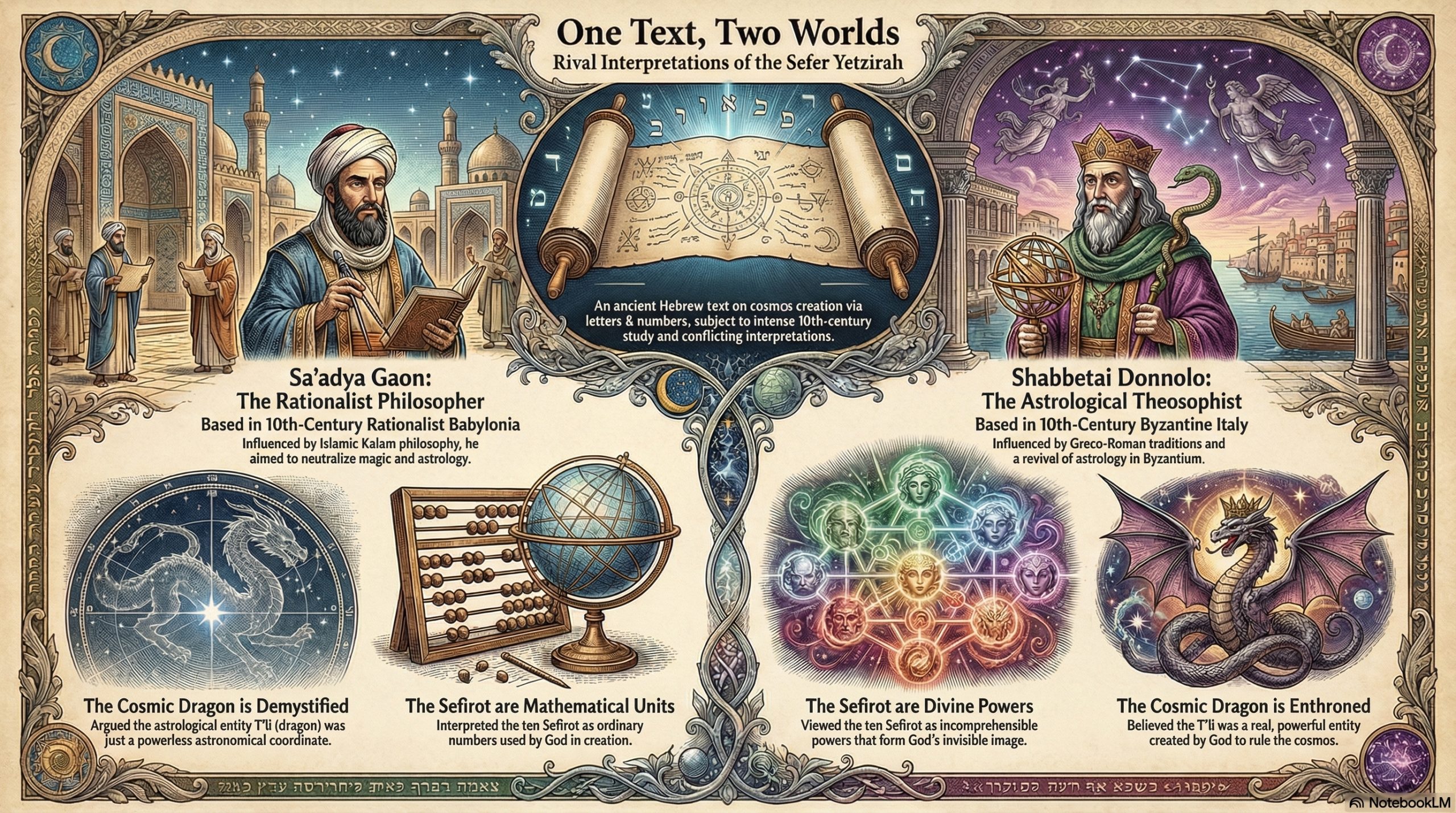

This presentation explores the pivotal 10th-century divergence in Jewish thought regarding the Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Formation). By examining the lives and works of two distinct thinkers—Sa’adya Gaon in Babylonia and Shabbetai Donnolo in Byzantine Italy—we see how a single, enigmatic text was forged into two radically different legacies: one rooted in rationalist philosophy and the other in theosophic mysticism. This divide not only shaped the interpretation of Hebrew letters and cosmic structures but also pushed back the timeline for the origins of Kabbalistic thought, demonstrating that the meaning of sacred texts is never static but actively shaped by its cultural environment

[Brief overview video on our YouTube channel at Rachav Foundation – YouTube along with many others.]

PLEASE CONSIDER SUBSCRIBING

Welcome to “The Crossroads of Meaning.” Today, we will examine how the 10th century became a defining moment for Jewish mysticism, as a single ancient text began to forge two very different futures

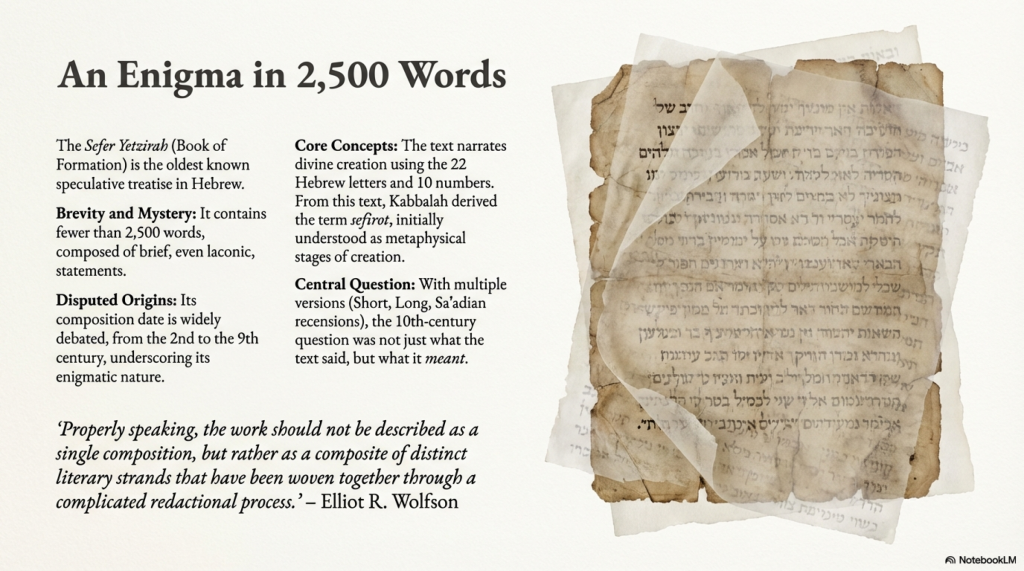

An Enigma in 2,500 Words

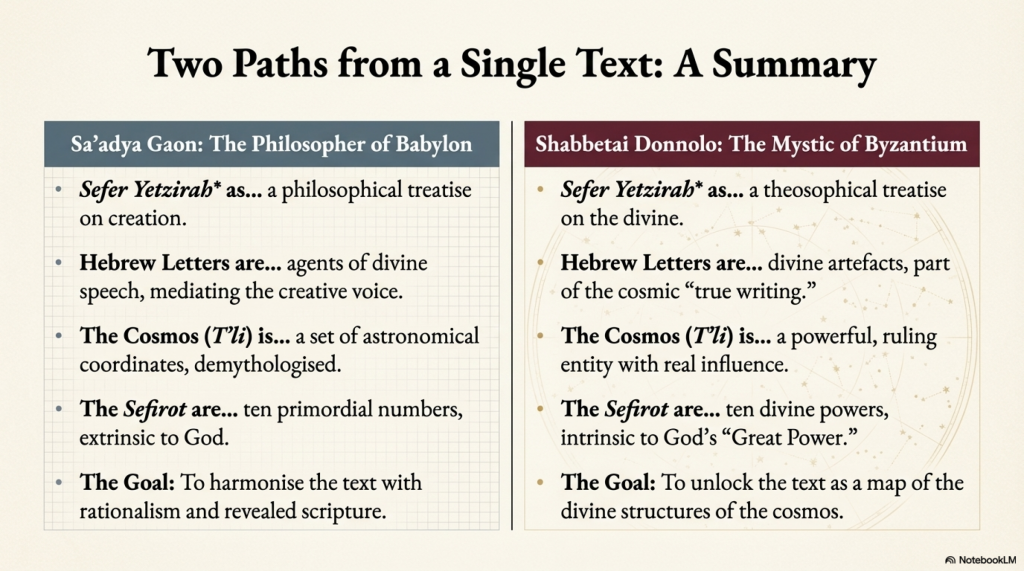

The Sefer Yetzirah, or Book of Formation, is the oldest known speculative treatise written in Hebrew. It is remarkably brief—fewer than 2,500 words—composed of laconic, mysterious statements. Its origins are a matter of intense debate, with proposed dates ranging from the 2nd to the 9th century. At its core, the text describes divine creation through the use of 22 Hebrew letters and 10 numbers, introducing the term sefirot. Scholars like Elliot Wolfson suggest the work is a composite of distinct literary strands woven together over time.

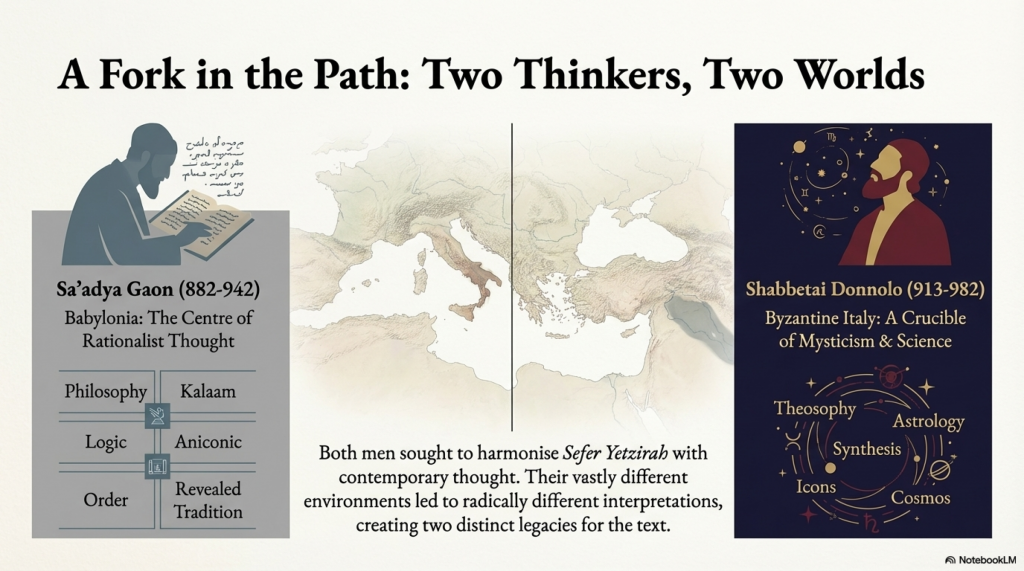

A Fork in the Path

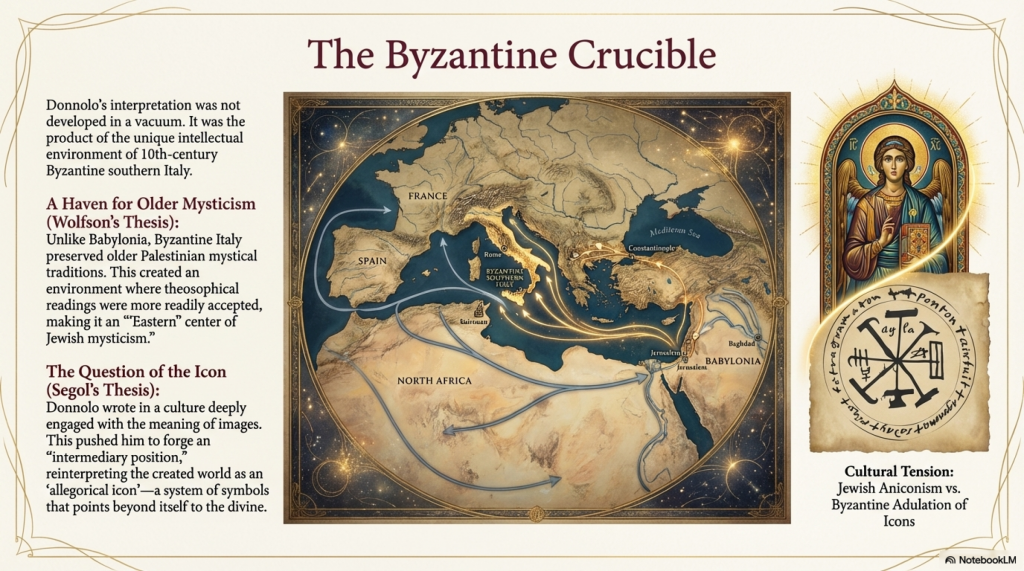

In the 10th century, two thinkers in vastly different worlds sought to harmonize this text with contemporary thought. In Babylonia, Sa’adya Gaon (882–942) operated in a center of rationalist thought, prioritizing logic, philosophy, and “Kalaam”. Meanwhile, in Byzantine Italy, Shabbetai Donnolo (913–982) lived in a crucible of mysticism and science, where astrology and theosophy flourished.

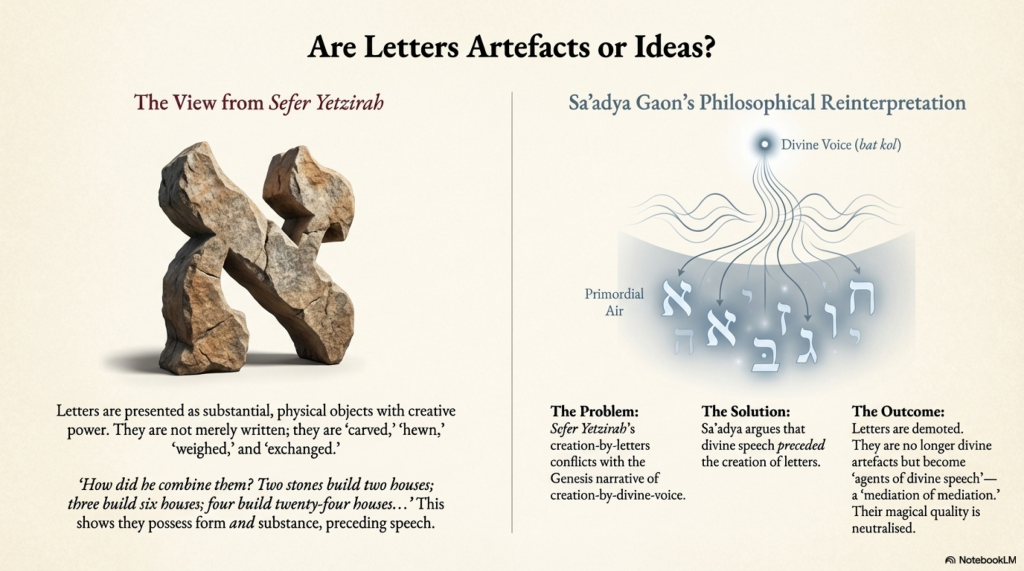

Are Letters Artefacts or Ideas?

The Sefer Yetzirah describes letters as physical objects—hewn, weighed, and combined like “stones” to build “houses”. Sa’adya Gaon saw a problem: this conflicted with the Genesis narrative of creation by divine voice. His solution was to demote the letters from creative artefacts to “agents of divine speech”—a “mediation of mediation” that neutralized their magical quality.

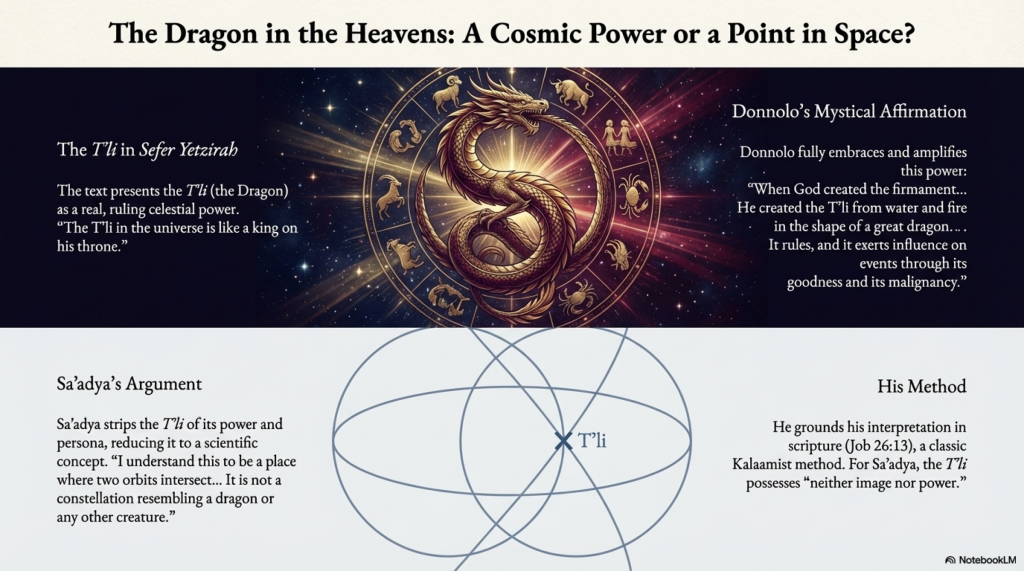

The Dragon in the Heavens

The text introduces the “T’li,” or the Dragon, as a ruling celestial power. Donnolo embraced this, describing it as a literal great dragon made of water and fire that exerts influence on worldly events. Sa’adya, however, demythologized the concept, reducing the T’li to a scientific point where two orbits intersect, possessing “neither image nor power”.

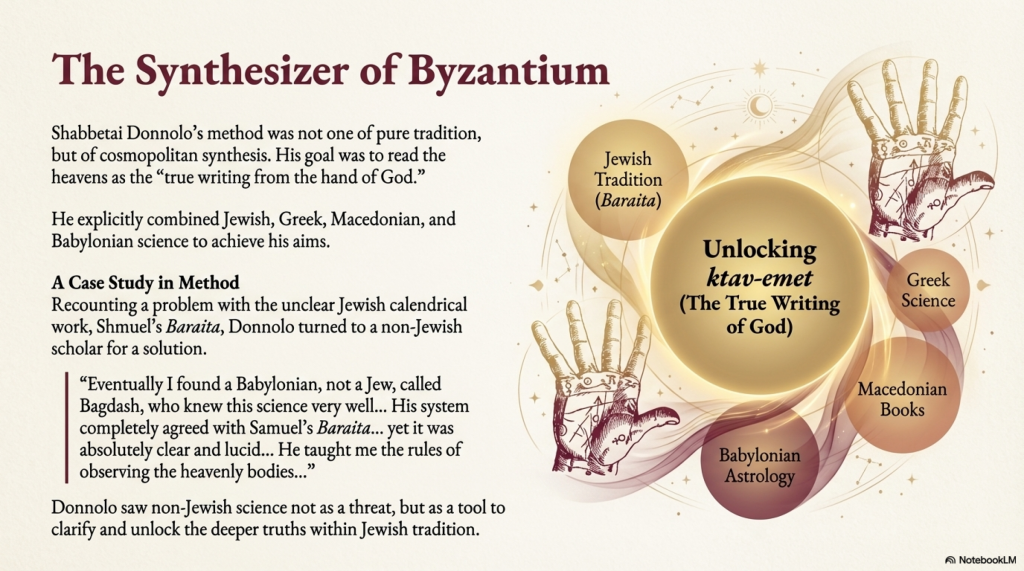

The Synthesizer of Byzantium

Donnolo’s method was one of cosmopolitan synthesis. He combined Jewish tradition with Greek, Macedonian, and Babylonian science. He even sought out non-Jewish scholars, like a Babylonian named Bagdash, to help clarify unclear Jewish astronomical texts, believing non-Jewish science could unlock the “true writing from the hand of God”.

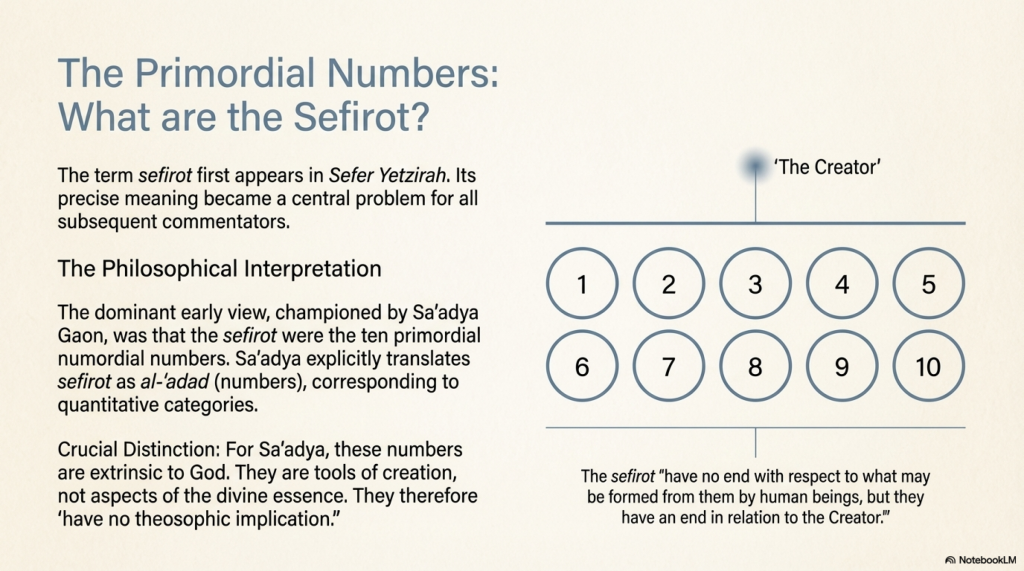

The Primordial Numbers (Sa’adya)

What are the sefirot? For Sa’adya Gaon, they are simply primordial numbers (al-‘adad). Crucially, he viewed them as extrinsic to God—they are tools for creation, not part of the divine essence, and therefore have no theosophic or mystical implication.

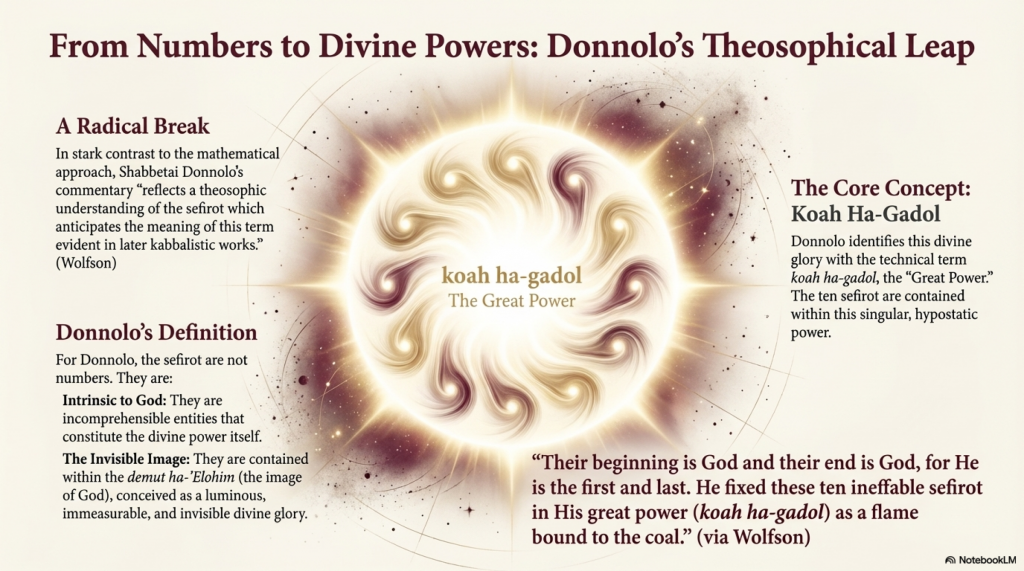

From Numbers to Divine Powers (Donnolo)

Donnolo made a radical break from this mathematical view. He interpreted the sefirot as divine powers intrinsic to God’s “Great Power” (koah ha-gadol). In his view, the sefirot are contained within the “image of God,” described as a flame bound to a coal.

The Unknowable Sefirot

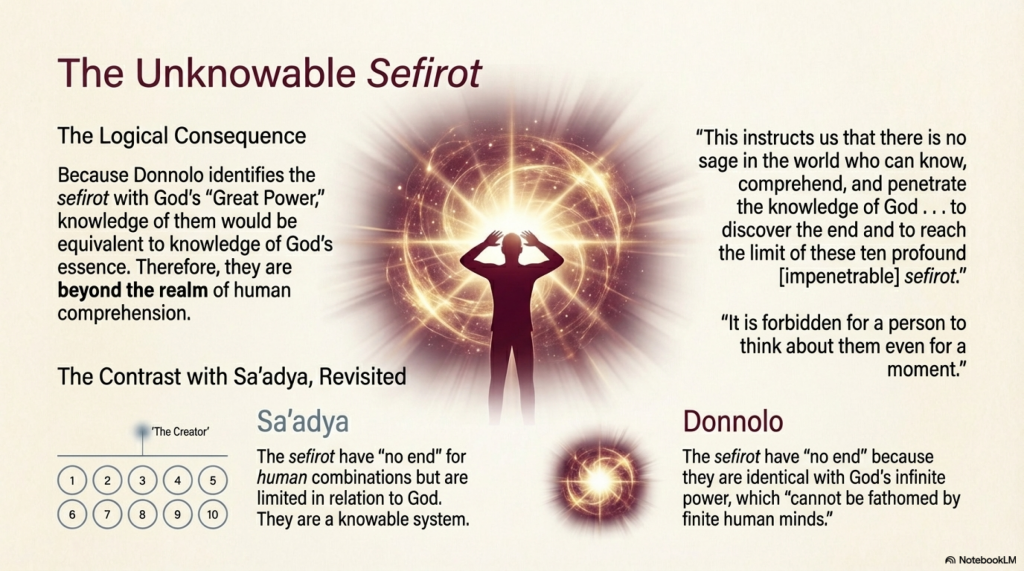

This led to a major logical divergence. Because Sa’adya saw sefirot as a knowable system of numbers, they were limited in relation to God but potentially penetrable by humans. Donnolo argued the opposite: since the sefirot are identical to God’s infinite power, they are beyond human comprehension and “forbidden” to think about even for a moment.

Two Paths Summary

To summarize: Sa’adya Gaon treated Sefer Yetzirah as a philosophical treatise, demythologizing the cosmos to harmonize with rationalism. Shabbetai Donnolo treated it as a theosophical map, viewing letters and the cosmos as powerful divine structures to be unlocked.

The Byzantine Crucible

Why was Donnolo’s view so different? Byzantine Italy preserved older Palestinian mystical traditions that Babylonia did not. Furthermore, living in a culture obsessed with religious icons pushed Donnolo to view the created world as an “allegorical icon”—a system of symbols pointing to the divine.

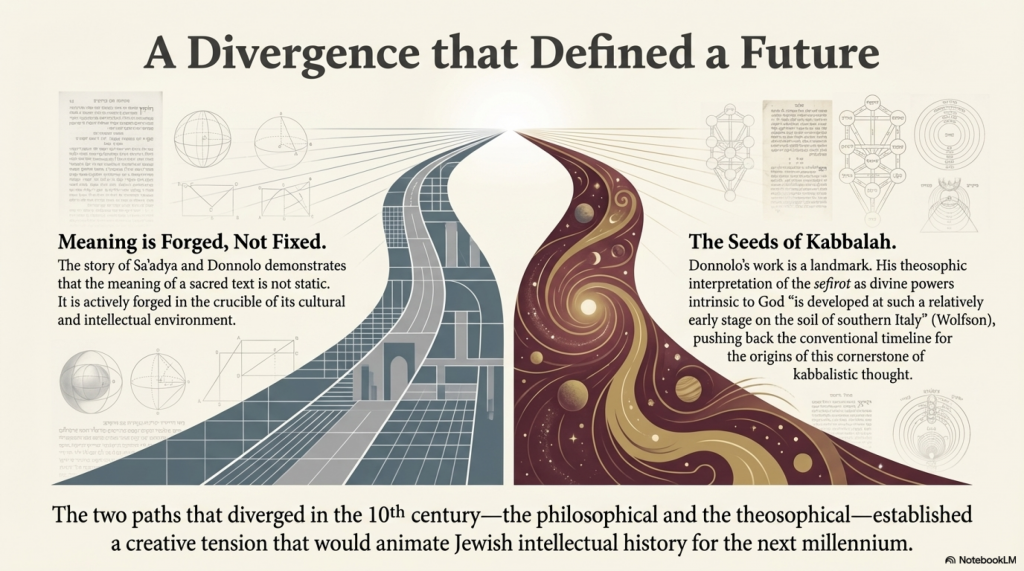

A Divergence that Defined a Future

These two paths—the philosophical and the theosophical—established a creative tension that animated Jewish history for a millennium. Donnolo’s work, in particular, is a landmark that pushes back the timeline for the origins of the cornerstone of Kabbalistic thought.

An in-depth audio look at this subject.