I. Introduction

The dramatic arrival of Alexander III of Macedon onto the historical stage in the late fourth century BCE coincided, within the framework of traditional Jewish chronology, with another momentous transition: the perceived cessation of classical prophecy (Nevuah) within Judaism. Alexander’s conquests irrevocably altered the political and cultural landscape of the ancient Near East, including Judea, ushering in the Hellenistic era.1 Concurrently, Jewish tradition maintains that the era characterized by direct divine communication through figures like Isaiah and Jeremiah drew to a close around this time, marking a fundamental shift in religious authority and the understanding of God’s interaction with Israel.4

This juxtaposition of a watershed historical event and a profound theological development presents a compelling area of inquiry. Alexander’s swift dismantling of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, under which Judea had existed for centuries 7, introduced new political realities and intense cultural currents stemming from Hellenism.3 The end of prophecy, conversely, signified the closure of a perceived channel of direct divine guidance, necessitating new modes of religious leadership and interpretation within Judaism.4 Exploring the potential association between these two occurrences delves into the heart of Jewish self-understanding during a pivotal period of transformation, examining how historical upheaval and theological evolution intersected in Jewish memory and tradition.

This report aims to meticulously examine the historical circumstances surrounding Alexander’s campaigns in the Levant, analyze relevant Jewish textual traditions—including biblical sources, Rabbinic literature (Talmud, Midrash, Seder Olam Rabbah), and the accounts of the historian Flavius Josephus—and explore the theological interpretations that have linked Alexander or the subsequent Hellenistic age to the end of prophecy. It will investigate the various reasons proposed within Jewish thought for the cessation of prophecy, detail the significant consequences of this cessation for Jewish religious life, particularly the consolidation of Rabbinic Judaism, compare diverse historical and theological perspectives on the matter, and synthesize these findings into a comprehensive analysis. The subsequent sections will address the historical context, the traditional understanding of prophecy’s end, the portrayal of Alexander in Jewish memory, the specific links proposed between Hellenism and prophecy’s cessation, the reasons adduced for this cessation, its consequences, and the scholarly debates surrounding these issues, before offering a concluding synthesis.

II. Historical Context: Alexander and Judea

Prior to Alexander’s conquests, Judea, known within the Achaemenid Persian Empire as the province of Yehud, existed under Persian suzerainty for roughly two centuries following the return from Babylonian exile.7 Internal governance was largely managed by the High Priest in Jerusalem, operating under the oversight of the Persian administration, likely the satrap of Coele-Syria.7 This period saw the rebuilding of the Second Temple, completed around 516/515 BCE under the encouragement of the prophets Haggai and Zechariah, and the subsequent religious and social reforms associated with figures like Ezra and Nehemiah in the mid-fifth century BCE.7 The leadership structure also included the “Great Assembly” (Anshei Knesset HaGedolah), a body of religious leaders and teachers considered foundational in the development of post-exilic Judaism.7 Life under Persian rule, while not fully independent, appears to have been relatively stable, allowing for the consolidation of Jewish religious life centered around the rebuilt Temple.

This long-standing geopolitical reality was shattered with extraordinary speed by Alexander the Great’s campaign against the Persian Empire. Launching his invasion by crossing the Hellespont in 334 BCE 1, Alexander secured a decisive early victory at the Battle of the Granicus River in May of that year.1 He rapidly campaigned through Asia Minor during 334-333 BCE.1 A pivotal confrontation occurred at the Battle of Issus in southern Asia Minor (near modern Turkey/Syria) around November 333 BCE, where Alexander defeated the main Persian army led by King Darius III himself.16

Following Issus, rather than immediately pursuing Darius eastward, Alexander turned south, securing the strategically vital Levant coastline.16 This brought his forces into Syria and Phoenicia during late 333 and 332 BCE.7 His advance was marked by the challenging sieges of Tyre (lasting approximately seven months, January to July/August 332 BCE) and Gaza (September-November 332 BCE).15 It was during or immediately after these sieges, in late 332 BCE, that Alexander’s presence was felt in or near Judea. Both Josephus and Talmudic traditions place encounters between Alexander and the Jewish leadership in Jerusalem around this time, specifically after the fall of Gaza.15 After securing the Levant, Alexander entered Egypt in the winter of 332-331 BCE, where he was welcomed and founded the city of Alexandria.2 He then turned east, decisively defeating Darius III again at the Battle of Gaugamela in Mesopotamia (October 331 BCE) 1, effectively sealing the fate of the Achaemenid Empire. Alexander continued his campaigns eastward into Persia, Central Asia, and India before his death in Babylon in June 323 BCE.2

The sheer velocity and transformative impact of Alexander’s conquests cannot be overstated. Within a few years, the familiar Persian hegemony that had defined the political world for Judea for two centuries was replaced by Macedonian-Greek rule, initiating the Hellenistic period.1 This dramatic historical rupture, the swift replacement of a long-standing, stable empire with a dynamic, culturally distinct power, likely generated a profound sense of epochal change among contemporary populations, including those in Judea. While this historical upheaval does not necessitate a causal link to the end of prophecy, the perception of such a sharp break with the past could easily have provided fertile ground for later generations to retrospectively interpret this period as a fitting marker for the conclusion of the prophetic era. The arrival of a new, powerful, and culturally different force could foster an environment where established paradigms, such as ongoing classical prophecy, felt less certain or were seen as belonging definitively to a previous age. The historical break caused by Alexander could thus be viewed, through a theological lens, as coinciding with the theological break represented by prophecy’s cessation, both marking the transition to the Hellenistic and post-prophetic world.

To visualize the temporal proximity of these events, the following timeline compares key moments in Alexander’s campaign in the region with the traditional Judean context:

Comparative Timeline: Alexander’s Campaign and Judean Context

| Year (BCE) | Key Event in Alexander’s Campaign (Levant/Egypt Focus) | Traditional High Priest/Judean Event (Approximate) |

| 334 | Crosses Hellespont; Battle of Granicus 1 | Jaddua likely High Priest 7 |

| 333 | Campaigns in Asia Minor; Battle of Issus (Nov) 16 | Jaddua likely High Priest 7 |

| 332 | Siege of Tyre (Jan-Jul/Aug); Siege of Gaza (Sep-Nov) 15 | Jaddua High Priest; Josephus/Talmud place Alexander’s interaction with Jerusalem/High Priest (Jaddua/Simon the Just) after Gaza (late 332 BCE) 15 |

| 332-331 | Enters Egypt; Founds Alexandria (Winter) 2 | Jaddua High Priest 7 |

| 331 | Campaigns in Mesopotamia; Battle of Gaugamela (Oct) 1 | Jaddua High Priest 7 |

| … | … | … |

| c. 330 | Death of Darius III 16 | Jaddua likely still High Priest 7 |

| … | … | … |

| 323 | Death of Alexander in Babylon (June) 2 | Jaddua may have died shortly after; succeeded by Onias I 7 (Simon the Just, son of Onias I, active later 7) |

This timeline visually juxtaposes Alexander’s rapid movements through the Levant with the tenure of the High Priests traditionally associated with him in Jewish sources, grounding the subsequent discussion of traditional chronologies and theological interpretations in the established historical sequence.

III. The End of Prophecy in Jewish Tradition

The mainstream view within Rabbinic Judaism holds that the era of classical prophecy, known as Nevuah, concluded during the early Second Temple period.4 This form of direct divine communication, exemplified by the biblical prophets, is not expected to manifest again in its fullness until the arrival of the Messiah and the Messianic age.4

Jewish tradition identifies the final figures in the line of canonical prophets as Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi.4 These prophets were active during the critical period of the return from Babylonian exile and the rebuilding of the Second Temple, primarily in the late sixth and early fifth centuries BCE.12 Their messages focused on encouraging the rebuilding efforts, addressing the community’s spiritual state, and navigating the challenges of re-establishing Jewish life in Judea under Persian rule.12 Among these three, Malachi is generally regarded as the very last prophet, whose work marks the close of the prophetic canon.4

This understanding is explicitly articulated in key Talmudic passages. Tractates Yoma 9b, Sanhedrin 11a, and Sotah 48b state that following the deaths of Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, the Holy Spirit (Ruach HaKodesh), often equated with the spirit of prophecy, departed from Israel.6 This departure is listed in Yoma 21b as one of the five essential elements present in the First Temple but lacking in the Second, highlighting its significance.4

A crucial source for the timing of this cessation, particularly in relation to Alexander the Great, is the Seder Olam Rabbah. This Hebrew chronicle, traditionally attributed to the 2nd-century CE Tanna, Rabbi Yose ben Halafta, provides a chronology of biblical and post-biblical events from Creation up to the Bar Kokhba revolt.35 Chapter 30 of Seder Olam makes an explicit connection, stating that prophecy ceased at the time of Alexander the Great.4 One formulation of this statement reads: “Until that time [Alexander the Macedon, who ruled 12 years] the prophets had prophesied in the holy spirit. From then on, incline your ear and listen to the words of the Sages”.32

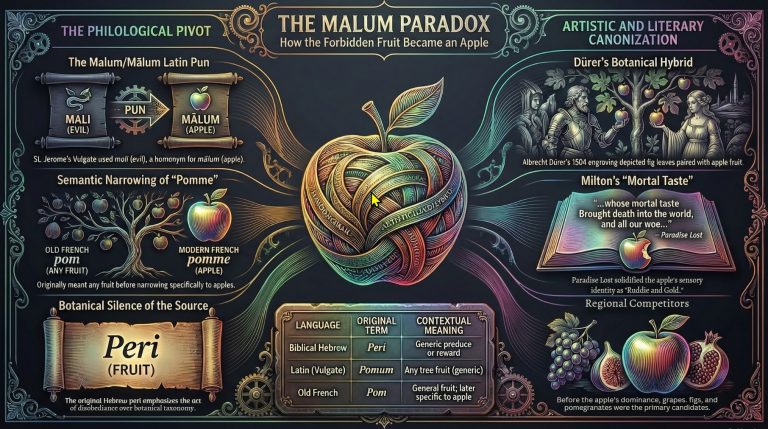

However, this chronological placement relies on Seder Olam’s unique and historically problematic timeline. A major discrepancy exists between Rabbinic chronology, based largely on Seder Olam, and the chronology established by secular historical scholarship, particularly concerning the duration of the Persian Empire’s rule over Judea.31 While historical records indicate the Persian period lasted over 200 years (from Cyrus’s conquest of Babylon c. 539 BCE to Alexander’s conquest c. 332 BCE), Seder Olam drastically compresses this era, assigning it only 34 years 36 or sometimes cited as 52 years.31 This compression appears to be a deliberate theological calculation, likely driven by a desire to reconcile the historical timeline with a specific interpretation of the seventy weeks prophecy in the Book of Daniel (Daniel 9:24), which was understood by some Sages to span the period from the destruction of the First Temple to the destruction of the Second Temple.36 By shortening the Persian period, Seder Olam places Alexander’s conquest significantly later than historical dating, around 316-312 BCE in the traditional Jewish calendar 18, effectively positioning his arrival immediately following the traditional lifespan of the last prophets.

This chronological adjustment is not merely a historical error but reflects a theological structuring of history. Seder Olam constructs a narrative where world history pivots around key moments in Jewish theological understanding. Compressing the Persian era allows Alexander’s arrival to serve as the precise hinge point marking the transition from the biblical era of direct prophecy to the subsequent era defined by Rabbinic interpretation and the authority of the Sages, as explicitly stated in the text (“From then on… listen to the words of the Sages” 32). This suggests that the Rabbis responsible for this tradition were not simply recording history as it occurred but were actively shaping a historical narrative to align with their interpretation of divine providence and the fulfillment of biblical prophecy, even where it conflicted with external historical accounts. Consequently, the link established in Seder Olam between Alexander and the end of prophecy is primarily a product of this theological framework, rather than a reflection of direct historical causality.

The following table illustrates the chronological differences between the Seder Olam framework and standard secular historical dating, highlighting the “missing years” 41 primarily located within the Persian period:

Chronological Comparison: Seder Olam vs. Secular History

| Event | Seder Olam Implied Date (BCE) | Secular Date (BCE) | Approximate Difference (Years) |

| Destruction of First Temple | 422 BCE 40 | 587/586 BCE | ~165 |

| Edict of Cyrus / Start of Persian Period | 370 BCE 40 | c. 539 BCE | ~169 |

| Completion of Second Temple | c. 352 BCE (Implied) | c. 516 BCE | ~164 |

| End of Persian Rule / Alexander’s Conquest | 318/316 BCE 40 | c. 332 BCE | ~186 |

| Destruction of Second Temple | 68 CE 37 or 70 CE | 70 CE | 0-2 |

(Note: Seder Olam dates are approximate calculations based on its internal chronology, particularly the 490 years between Destructions and the compressed Persian period. Variations exist in precise calculations.40 The core discrepancy of ~164-165 years in the Persian era is consistent.40)

This table quantifies the chronological divergence, demonstrating how Seder Olam’s framework creates a timeline where Alexander’s arrival appears to align closely with the end of the biblical narrative and the era of the last prophets (Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi, active c. 520-450 BCE). This manufactured proximity makes the traditional association between Alexander and the end of prophecy seem plausible within that specific theological-chronological system, clarifying that the discussion involves fundamentally different historical frameworks.

IV. Alexander the Great in Jewish Memory

Beyond the chronological linkage in Seder Olam, Alexander the Great figures prominently in Jewish historical memory through vivid narratives found in the writings of Flavius Josephus and in the Talmud. These accounts, while differing in details, share a common theme of interaction between the conqueror and the Jewish leadership, particularly the High Priest.

In his Jewish Antiquities (Book 11, sections 317-345), Josephus relates a detailed story set during Alexander’s campaign after the siege of Gaza (late 332 BCE).19 According to Josephus, Alexander had previously demanded aid from the High Priest Jaddua during the siege of Tyre, but Jaddua refused, citing his oath of loyalty to the Persian King Darius III.19 Enraged, Alexander threatened to march on Jerusalem after conquering Tyre and Gaza.19 However, Jaddua, warned by God in a dream after offering sacrifices, prepared to meet Alexander not with resistance, but with ceremony.19 Dressed in his full pontifical vestments, including the miter with the golden plate bearing God’s name, and accompanied by priests in fine linen and the populace in white garments, Jaddua led a procession out of the city to meet the approaching conqueror.19 Upon seeing the High Priest, Alexander, to the astonishment of his own retinue (particularly his general Parmenion), approached alone and bowed down, adoring the name of God on the miter.19 Alexander explained that he was not adoring Jaddua himself, but the God who honored him with the priesthood. He recounted seeing this very figure in this exact attire in a dream while still in Macedonia, a vision that encouraged him to undertake the conquest of Asia, promising divine guidance and victory over the Persians.19 Alexander then entered Jerusalem peacefully, offered sacrifices in the Temple according to Jaddua’s direction, and treated the priesthood magnanimously.19 Josephus adds that Alexander was shown the Book of Daniel, wherein a prophecy foretold that a Greek would destroy the Persian Empire; Alexander supposedly identified himself as the fulfillment of this prophecy.20 Consequently, he granted the Jews significant privileges, including the right to live according to their ancestral laws and exemption from tribute during the Sabbatical year, extending similar considerations to Jews in Babylon and Media.20 This favorable treatment is contrasted sharply with his dealings with the Samaritans, who also sought favor but were rebuffed.20

Talmudic literature contains similar narratives, though often substituting Shimon HaTzadik (Simon the Just) for Jaddua as the High Priest who met Alexander.10 Simon the Just is traditionally considered Jaddua’s successor or grandson, active slightly later.7 In a version found in Tractate Yoma (69a), the Samaritans maliciously petition Alexander to destroy the Jerusalem Temple.18 Shimon HaTzadik, dressed in priestly vestments and accompanied by elders bearing torches, goes out to meet Alexander, often specified as reaching him at Antipatris.10 As in Josephus’s account, Alexander dismounts and bows before the High Priest, explaining to his puzzled companions that he sees an image of this man leading him to victory in battle.10 Alexander then grants favors to the Jews and, in this version, hands over the Samaritan instigators to the Jews, who reportedly punished them severely (dragging them behind horses to Mount Gerizim and plowing the site of their temple).10 Another detail sometimes included is Alexander requesting his statue be placed in the Temple, which the High Priest diplomatically deflects by promising instead that all sons born to priests that year would be named Alexander in his honor.47

Despite the prominence of these stories in Jewish tradition, modern historical scholarship widely regards them as legendary rather than factual accounts.21 Several factors contribute to this skepticism: the lack of any corroborating evidence in contemporary Greek historical sources detailing Alexander’s campaigns; the presence of clearly legendary elements such as divine dreams and prophetic visions recognized by Alexander; chronological inconsistencies regarding whether Jaddua or Shimon HaTzadik was the High Priest involved; the anachronistic detail of Alexander being shown the Book of Daniel, whose final form and canonization are generally dated much later by critical scholars 21; and the overtly apologetic tone, particularly the stark contrast drawn between the favored Jews and the spurned Samaritans, suggesting the stories served internal Jewish polemical purposes.21

However, some scholars acknowledge the possibility of a historical kernel, such as Alexander indeed receiving the peaceful submission of Jerusalem and granting a degree of local autonomy, consistent with his general policies in other regions.48 Josephus, while incorporating legendary material, often provides a generally reliable historical framework for the period.49 More significantly, the endurance and function of these legends within Jewish tradition are undeniable.50

These narratives, irrespective of their literal accuracy, offer invaluable insight into Jewish self-perception and theological negotiation within the nascent Hellenistic world. They represent a powerful attempt to “Judaize” Alexander, the paramount figure of the new era, by integrating him into a Jewish theological framework. His world-altering success is depicted not merely as a result of military genius, but as divinely sanctioned, mediated through the Jewish High Priest and foretold in Jewish scripture (Daniel). The stories function to assert Jewish theological preeminence and the enduring reality of God’s providence for Israel, even in a time of political vulnerability under foreign rule. They act as a form of cultural memory, shaping how subsequent generations of Jews understood their relationship with dominant gentile powers and affirming the continuity of God’s covenant and protection. By portraying the world conqueror bowing to the sanctity of the Temple and the authority of the High Priest, these traditions bolstered Jewish identity and theological confidence in the face of the potentially overwhelming cultural and political force of Hellenism.

V. Exploring the Link: Hellenism and the Cessation of Prophecy

The association between Alexander the Great’s arrival, the subsequent Hellenistic era, and the cessation of prophecy in Jewish tradition is multifaceted, ranging from direct chronological claims to more symbolic and theological interpretations.

The most direct link is found in the traditional chronology presented by Seder Olam Rabbah. As previously discussed, this 2nd-century CE work explicitly synchronizes the end of the prophetic era with the time of Alexander the Great, using his reign as the demarcation point between the age of prophets and the age of sages.4 This placement, achieved through a significant compression of the preceding Persian period 36, positions Alexander as the immediate historical successor to the last biblical prophets within this specific theological timeline.

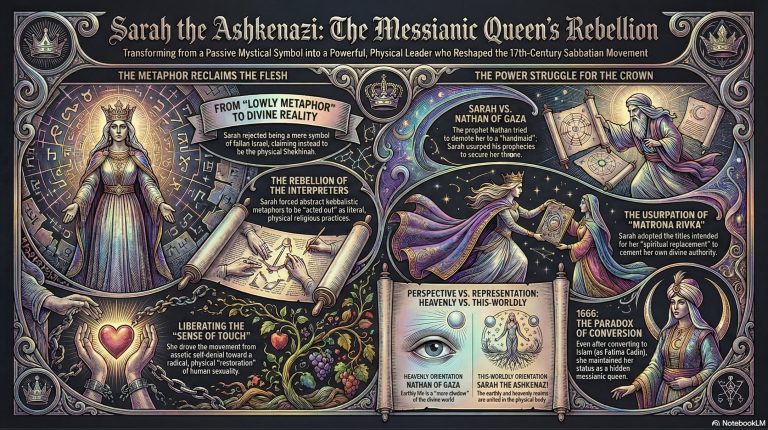

Beyond this direct chronological assertion, deeper symbolic and theological links have been drawn between Hellenism and the end of prophecy. One prominent interpretation views the advent of Hellenistic culture, with its emphasis on human reason and philosophy, as coinciding with a divinely ordained metaphysical shift in how God communicated with humanity.4 Thinkers like Rabbi Zadok HaKohen of Lublin explicitly noted a parallel development: just as prophecy ceased in Israel, Greek philosophy—termed “mortal wisdom”—rose to prominence.4 This perspective suggests that the historical period dominated by Greek rationalism was also the period when God’s primary mode of revelation transitioned from direct prophetic inspiration to the interpretation of the written Torah through human reason, guided by the Oral Law. The era of Alexander, therefore, marks not just a political change but a spiritual-intellectual watershed.

Another related interpretation posits Hellenism, symbolized by Alexander, as an antithetical force or challenge to Judaism.10 Greek culture and philosophy, with their different values and modes of understanding the world, presented a potential threat to Jewish tradition.53 In this view, the cessation of prophecy necessitated a new, robust Jewish response: the intensified focus on the study and development of the Oral Law.4 This intellectual and legal framework became the primary means of preserving Jewish identity and practice in the face of Hellenistic cultural pressure. Paradoxically, some Talmudic interpretations suggest that Alexander’s success (representing the rise of Hellenism) was enabled by the spiritual merit of the High Priest Shimon HaTzadik, implying that the new era was, in a complex way, born from the spiritual power of the era that was passing.10

Furthermore, the influence of the Hellenistic context is evident even in texts dealing with prophecy from that era. The Book of Daniel, which critical scholarship often dates to the Hellenistic period (specifically during the persecutions under the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, a crisis stemming from forced Hellenization 54), utilizes apocalyptic visions—a literary form related to prophecy—to interpret contemporary history.55 Daniel depicts Alexander as a powerful figure (the symbolic “he-goat” with a great horn) whose empire rises swiftly and then fragments, mirroring historical events.32 This indicates that even as classical prophecy was understood to be waning or concluded, new modes of interpreting history through a divine lens, heavily shaped by the political and cultural realities of the Hellenistic world, were emerging within Judaism.

The historical backdrop for these interpretations is the undeniable reality of Hellenization in Judea following Alexander’s conquests.3 Greek language became widespread, elements of Greek culture and administration were adopted, and Greek philosophical ideas permeated the intellectual environment, influencing segments of the Jewish population, including the priestly aristocracy.3 This cultural interaction was not always smooth, leading to significant internal tensions and ultimately contributing to events like the Maccabean Revolt in the 2nd century BCE, which was, in part, a reaction against forced Hellenization.53

Considering these factors, the traditional association of Alexander and Hellenism with the end of prophecy can be understood as a sophisticated theological strategy for contextualizing and managing the impact of a powerful external culture. By framing the rise of Greek rationalism as concurrent with a divinely willed shift away from direct prophecy towards the centrality of Torah study and rabbinic interpretation, Jewish tradition could acknowledge the historical significance and intellectual force of Hellenism while simultaneously asserting the continuity and adaptation of Jewish revelation. This narrative transforms a potential cultural challenge into a predetermined stage in God’s plan for Israel, ultimately reinforcing the authority of the Sages and the importance of the Oral Law as the primary means of accessing divine will in the new era. It integrates the historical reality of Hellenism into a theological framework that preserves Jewish distinctiveness and validates the emerging Rabbinic mode of religious life.

VI. Reasons for the Cessation of Prophecy

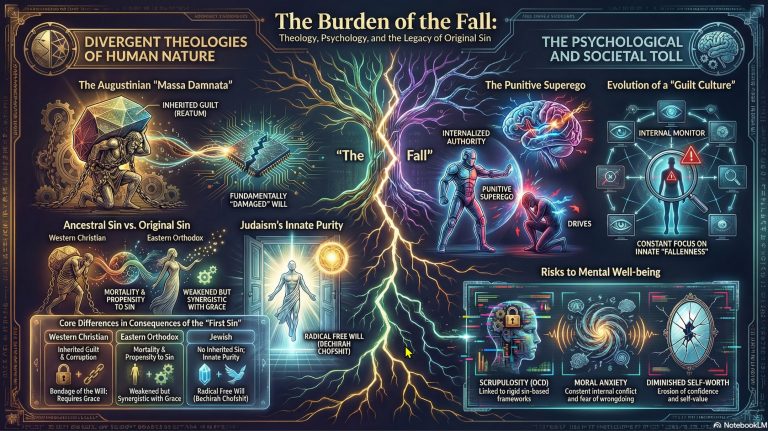

Jewish tradition offers a variety of explanations for why the era of classical prophecy came to an end. These reasons, found across Talmudic, Midrashic, and later rabbinic sources, are not mutually exclusive and often reflect attempts to find theological meaning in the perceived absence of prophetic figures comparable to those of the biblical past. They can be broadly categorized into explanations based on sin, historical catastrophe, and metaphysical or theological transitions.

One prominent line of reasoning attributes the cessation of prophecy to national sinfulness, viewing its withdrawal as a form of divine punishment.4 This aligns with the general prophetic theme that disobedience leads to negative consequences. Specific failings cited include a general lack of fidelity to the Torah 4, the people’s mockery and rejection of the prophets themselves 4, as mentioned in Avot D’Rabbi Nathan, and, significantly, the failure of a large portion of the Jewish population to return to Judea from the Babylonian exile when permitted by Cyrus the Great.4 Sources like Pesikta Rabbati and commentators like Maharsha link the diminished spiritual state of the post-exilic community, due to this incomplete return, directly to the loss of prophecy.4 This perspective echoes the much earlier prediction attributed to the prophet Amos (8:11-12) of a future “famine… for hearing the words of the Lord”.4

Another category of explanation links the end of prophecy to major historical calamities, primarily the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE and the subsequent Babylonian exile.4 The prophet Ezekiel vividly described the departure of the Shekhinah, the tangible Divine Presence, from the Temple due to the people’s idolatry.4 Rabbinic sources explicitly state that the Holy Spirit, synonymous with prophecy, was one of the key elements present in Solomon’s Temple but absent from the Second Temple.4 While Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi did prophesy after the destruction, some traditions view their prophecy as diminished or merely transmitting earlier messages.4 The trauma of destruction and exile, and the perceived withdrawal of God’s manifest presence, dealt a severe blow from which classical prophecy, in this view, never fully recovered. Maimonides also connects the cessation to exile, albeit through a more naturalistic lens, arguing that the sadness, lack of tranquility, and subjugation inherent in exile prevented the cultivation of the joyful and stable disposition necessary for the “imaginative faculty” to receive prophecy.24

A third set of reasons posits a more fundamental metaphysical or theological transition, suggesting a deliberate shift in the divine plan or the spiritual nature of the era.4 A key idea here is the connection between prophecy and idolatry. During the First Temple period, the intense societal draw towards idolatry, often involving practices perceived as magical or supernatural, was counterbalanced by the equally powerful manifestations of divine prophecy.4 However, Talmudic sources note that the inclination towards idolatry significantly weakened during the Second Temple period (Yoma 69b).4 Consequently, figures like Rabbi Yehudah HeHasid argued that prophecy was no longer necessary as a counterbalance.4 This ties into the broader concept of a shift from an era dominated by direct divine intervention and revelation (prophecy, miracles) to an era emphasizing human reason, ethical choice, and the interpretation of Torah through the Oral Law.4 R. Zadok HaKohen saw this as a necessary development for the flourishing of the Oral Law 4, while Malbim suggested the core prophetic messages had already been delivered.4 Some thinkers, like R. Eliyahu Dessler, argued that with the decline of idolatry’s pull, continued overt prophecy would have overwhelmed human free will, making genuine faith and choice impossible; its cessation was thus necessary to preserve meaningful human agency.4

Finally, the cessation of prophecy is often implicitly or explicitly linked to the closing of the Hebrew Bible canon (Tanakh).58 Josephus, writing in the late first century CE, articulated this connection when he stated that Jewish histories written after the time of the Persian king Artaxerxes (roughly the era of Ezra and Nehemiah, overlapping with the last prophets) were not held in the same esteem as the earlier scriptures because “there has not been an exact succession of prophets since that time”.6 This suggests a view where the authority to produce divinely inspired scripture was tied to the classical prophetic line. Once that line ended and the foundational texts were compiled and recognized as authoritative (canonized), the need for ongoing, canon-worthy prophecy diminished.59 Religious authority then shifted decisively towards the interpretation and application of this now-closed body of sacred literature. While the precise timing and process of canonization remain subjects of scholarly debate 60, the perceived link between the end of prophecy and the finalization of the Tanakh is a significant factor in understanding this transition.

The existence of multiple, diverse explanations for prophecy’s end points towards a complex reality. It suggests that the “cessation” was likely not a single, abrupt event with a universally acknowledged cause, but rather a gradual process or transformation that was perceived and interpreted retrospectively. Faced with the absence of contemporary figures wielding the same authority and direct divine connection attributed to the biblical prophets, later generations sought theological meaning in this absence. They connected it to pivotal historical events (Temple destruction, exile, Alexander’s conquests), national moral failings, or fundamental shifts in the divine-human relationship. This process of attributing reasons reflects a deep-seated need within the tradition to understand history theologically, to maintain a sense of divine providence even amidst perceived silence, and to legitimize the transition to a new mode of religious life centered on sacred text and its interpretation by the Sages. The “reasons” offered are thus as much a reflection of the developing theology of Rabbinic Judaism as they are potential historical causes.

VII. Consequences: The Post-Prophetic Era in Judaism

The perceived cessation of classical prophecy was not merely the end of an era; it acted as a profound catalyst, fundamentally reshaping Jewish religious life, authority structures, and the primary modes of engaging with the divine. The consequences of this transition were far-reaching, leading directly to the development and consolidation of Rabbinic Judaism.

With the absence of prophets serving as direct conduits for God’s word, a vacuum in religious authority emerged. This vacuum was filled by the Sages (Ḥakhamim, later known as Rabbis), who became the primary interpreters of God’s will.6 Their authority derived not from direct revelation, but from their mastery of the written Torah and the traditions of the Oral Law (Torah she-be’al Peh). The Talmudic assertion, “A Sage is greater than a Prophet” (Bava Batra 12a), encapsulates this significant shift in prestige and practical authority.6 While prophets delivered divine pronouncements, the Sages engaged in the meticulous work of interpreting scripture, resolving legal questions, and applying timeless principles to new circumstances. They effectively translated the often broad, ethical imperatives of the prophets into detailed, practical guidance for individual and communal life.11 Examples include transforming prophetic calls for justice and peace into concrete communal practices regarding social welfare and inter-communal relations.68

This shift placed the Torah, both Written and Oral, at the absolute center of Jewish life. Discerning God’s will became primarily an act of textual interpretation and legal reasoning.4 Consequently, sophisticated methods of interpretation (Midrash) flourished, and the systematic development and codification of Jewish law (Halakha) became the core religious enterprise.4 Figures like Rav Kook conceptualized this as Halakha’s details coming to the fore once the overwhelming “daylight” of direct prophecy receded.11 The Netziv described a move from ad hoc, prophetically inspired rulings in earlier times to more systematic, analytical halachic reasoning in the post-prophetic era.11 Torah study itself evolved into a primary means of connecting with the divine, an intellectual and spiritual discipline aimed at uncovering God’s wisdom embedded in the text.

While classical prophecy ceased, the tradition acknowledged the continuation of lesser forms of divine communication or guidance. The most frequently mentioned is the Bat Kol (literally “daughter of a voice” or “echo”), described as a heavenly voice that could pronounce judgments or convey messages.6 Talmudic stories recount the Bat Kol intervening in halachic disputes, famously siding with Beit Hillel over Beit Shammai 74, although its authority was notably rejected by Rabbi Yehoshua in the “Oven of Akhnai” debate in favor of majority rabbinic reasoning, based on the principle that the Torah “is not in heaven” (Deuteronomy 30:12).74 This highlights the subordination of even perceived heavenly voices to the established interpretive authority of the Sages. Other concepts include Ruach HaKodesh (the Holy Spirit), sometimes understood as a level of divine inspiration below prophecy but still accessible to the righteous 6, and the continued potential for guidance through dreams.26 However, the dominant and authoritative mode remained the interpretation of Torah.

This transition also arguably fostered a shift in the nature of religious experience. The post-prophetic era demanded a more internalized and perhaps more mature form of piety.4 Connection with God became less dependent on external, overwhelming displays of divine power (miracles, prophecy) and more reliant on individual and communal effort in study, observance, and the application of reason to understand God’s will as expressed in the Torah.4

Ultimately, the cessation of prophecy served as a crucial catalyst for the evolution of Judaism. It necessitated the development of the robust intellectual and legal framework of Rabbinic Judaism, centered on the interpretation of the Written and Oral Torah. This shift proved vital for the religion’s resilience and adaptability, providing a portable and enduring foundation for Jewish life that could sustain the community through the loss of the Temple, the dispersion of the diaspora, and vastly changing historical circumstances. The acknowledgment of lesser forms of divine communication like the Bat Kol demonstrates a continued belief in God’s interaction with the world, but the ultimate authority granted to the Sages and their interpretation of Torah cemented the structure of Judaism as a text-centered, interpretation-based tradition. This transformation, spurred by the absence of prophets, was arguably essential for the long-term survival and flourishing of Judaism.

VIII. Comparative Perspectives and Scholarly Debate

The traditional Rabbinic understanding of the cessation of prophecy, while internally coherent within its own theological and chronological framework, faces challenges when examined through the lens of modern historical-critical scholarship and compared with the diversity of beliefs within Second Temple Judaism itself.

A primary point of divergence lies in chronology and textual dating. As established, the Seder Olam Rabbah’s timeline, which places Alexander the Great immediately after the last prophets 4, is considered historically inaccurate by modern scholars due to its compression of the Persian period.37 Furthermore, historical-critical dating methods often place the final composition of certain biblical books, most notably Daniel with its clear allusions to the Hellenistic period 47, after the traditional dating of Malachi (mid-5th century BCE).47 This challenges the traditional sequence and suggests that activity considered prophetic (like the apocalyptic visions in Daniel) occurred later than the supposed cessation point.

Moreover, evidence from the Second Temple period itself indicates that the Rabbinic view of a definitive end to prophecy with Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi was not universally held among all Jewish groups.6 The community associated with the Dead Sea Scrolls (likely related to the Essenes) clearly believed in ongoing divine inspiration and revelation.56 Their writings, particularly the Pesher texts, interpret biblical prophecies as being revealed and understood through inspired figures within their own community, such as the Teacher of Righteousness.85 This community saw itself as living in the “Last Days” and as the direct heir to the prophetic tradition, possessing the eschatological Spirit.6 This stands in contrast to the Rabbinic perspective that the Holy Spirit/prophecy had departed centuries earlier.85

The historian Flavius Josephus also presents a more nuanced picture. While acknowledging in Against Apion that the “exact succession of prophets” ended after Artaxerxes, thus explaining why later historical writings lacked the authority of the canonical scriptures 6, he frequently describes contemporaries whom he considers to possess prophetic gifts or foresight.6 Scholars suggest Josephus may distinguish between the authoritative biblical prophets and later figures, perhaps using different terminology (like mantis vs. prophetes), but he does not seem to believe all forms of prophetic activity had ceased.6

The context of early Christianity further highlights this diversity. The New Testament depicts figures like John the Baptist, Jesus himself, and others (e.g., Agabus in Acts 63) as prophets, and discusses prophecy as an active spiritual gift within the early church community.65 While distinct from Rabbinic Judaism, early Christianity emerged from the same milieu, demonstrating that belief in contemporary prophecy was a live option for some Jews in the late Second Temple and early post-Temple periods.

This leads to a scholarly debate regarding the precise nature of the “cessation.” Was it understood as an absolute end to all divine communication, or rather a decline, a transformation, or the end of a specific type of prophecy?.6 Some argue the cessation refers specifically to canonical prophecy – the end of prophets whose utterances were deemed worthy of inclusion in the authoritative scriptures.6 Others suggest it marked the end of the specific line of national prophets succeeding Moses, as outlined in Deuteronomy 18 91, without precluding other forms of inspiration. The Rabbinic use of the term “departed” (pasak) rather than “ceased” (batel) might also suggest a withdrawal or diminution rather than a complete termination.24

The existence of this debate and the evidence for alternative views within ancient Judaism suggest that the Rabbinic doctrine of cessation may have served not only as a theological explanation for a perceived reality but also potentially as a polemical tool. By defining the age of prophecy as definitively closed and locating authority solely within the interpretation of the established canon, the proto-Rabbinic and later Rabbinic movements could consolidate their own authority structure based on mastery of text and tradition. This implicitly delegitimized competing groups, such as the Qumran sectarians, apocalyptic visionaries, or early Christians, who claimed authority based on new or ongoing direct revelation. The declaration that prophecy had ended, therefore, can be viewed partly as an outcome of the internal religious dynamics and power struggles within Judaism during the turbulent late Second Temple and post-destruction periods, culminating in the ascendancy of the Rabbinic approach. Understanding the “cessation of prophecy” requires acknowledging this complex landscape of diverse beliefs and the historical processes that led to the dominance of the Rabbinic perspective.

IX. Synthesis and Conclusion

The question of an association between the arrival of Alexander the Great and the end of prophecy in Judaism navigates the complex intersection of established history, theological interpretation, and cultural memory. The traditional linkage, most explicitly articulated in the Seder Olam Rabbah, places Alexander’s conquest as the historical marker signifying the transition from the era of biblical prophets to the era of Rabbinic sages.4 However, this connection appears to be primarily theological and symbolic, embedded within a specific Rabbinic chronology that diverges significantly from secular historical accounts, particularly regarding the length of the Persian period.36 Rather than Alexander’s actions directly causing prophecy to cease, he functions within this traditional narrative as a pivotal figure heralding a new epoch—the Hellenistic age—which Rabbinic thought retrospectively aligned with the shift from direct divine revelation to interpretive engagement with the Torah.

A careful weighing of the evidence reveals a distinction between historical impact and theological narrative. Alexander’s conquests undeniably had a profound and lasting impact on Judea, initiating the Hellenistic period and introducing cultural and political forces that deeply influenced Jewish society and thought.2 The legends surrounding his interactions with the High Priest Jaddua or Simon the Just, while likely not historically literal 21, reflect a Jewish attempt to integrate this world-changing figure into their own theological framework, asserting divine providence and Jewish spiritual significance even under foreign domination.10 However, direct historical evidence demonstrating that Alexander’s arrival caused the cessation of prophecy is absent. The association stems primarily from the theological need to structure history and explain a perceived shift in divine communication, using the dramatic historical rupture caused by Alexander as a convenient and symbolically potent demarcation point.

The perceived end of prophecy, whenever and however it precisely occurred, had transformative and enduring consequences for Judaism. It catalyzed the rise of Rabbinic Judaism, shifting the locus of religious authority from prophets to sages, and centering religious life on the meticulous study and interpretation of the Written and Oral Torah (Halakha).4 This transition fostered new modes of discerning divine will through textual analysis and legal reasoning, acknowledged lesser forms of divine guidance like the Bat Kol 74, and arguably cultivated a more internalized form of religious experience based on human intellectual and ethical effort.24 This evolution proved crucial for Judaism’s adaptability and long-term survival, providing a resilient framework independent of political sovereignty or a central Temple.

In conclusion, while a direct causal link between Alexander the Great and the end of prophecy remains tenuous and largely confined to a specific traditional chronological framework, their association within Jewish thought is significant. It highlights the dynamic interplay between major historical events and the evolution of religious belief and practice. The narrative linking Alexander, Hellenism, and the shift away from prophecy reflects a profound Jewish engagement with history, an effort to contextualize cultural change within a divine plan, and the foundational transition that led to the enduring structure of Rabbinic Judaism, centered on the wisdom derived from Torah and its interpretation.

Works cited

- Wars of Alexander the Great – Wikipedia, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wars_of_Alexander_the_Great

- Alexander the Great – Wikipedia, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_the_Great

- Ancient Jewish History: Hellenism, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/hellenism-2

- The End of Prophecy: Malachi’s Position in the Spiritual Development of Israel, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.jewishideas.org/article/end-prophecy-malachis-position-spiritual-development-israel

- Prophets in Judaism – Wikipedia, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prophets_in_Judaism

- The Spirit of Prophecy in the Second Temple – Perspective Digest, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.perspectivedigest.org/archive/27-4/the-spirit-of-prophecy-in-the-second-temple

- Kingdoms of the Levant – Great Jews and High Priests of Judah (Canaan) – The History Files, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsMiddEast/CanaanIsraelitesGreatPriests.htm

- Judaism 200 Years Before Jesus: The Maccabean Revolt – The Bart Ehrman Blog, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://ehrmanblog.org/judaism-200-years-before-jesus-the-maccabean-revolt/

- Hellenistic, 4th-2nd Century – Judaism – Britannica, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Judaism/Hellenistic-Judaism-4th-century-bce-2nd-century-ce

- Alexander the Great and the Jewish High Priest – Aish.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://aish.com/48965601-3/

- The History of Halacha, from the Torah to Today – 18Forty, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://18forty.org/articles/the-history-of-halacha-torah-today/

- Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi: Prophecy in an Age of Uncertainty – Jewish Action, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://jewishaction.com/books/reviews/haggai-zechariah-malachi-prophecy-age-uncertainty/

- Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi – Embry Hills church of Christ, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://embryhills.com/media/uploads/public/Classes/Lesson%20Guide%2C%20Haggai%2C%20Zechariah%2C%20Malachi%2C%20Aug-20.pdf

- Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi: Back in the Land | My Jewish …, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/haggai-zechariah-and-malachi-back-in-the-land/

- When Alexander the Great came to Jerusalem | Bible Reading Archeology, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://biblereadingarcheology.com/2018/01/29/when-alexander-the-great-came-to-jerusalem/

- Alexander the Great: Chronology – Livius.org, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.livius.org/articles/person/alexander-the-great/alexander-the-great-5/

- The Conquests of Alexander the Great (334 bce–323 bce) | Encyclopedia.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/conquests-alexander-great-334-bce-323-bce

- Year 3424 – 336 BCE – Alexander of Macedonia – SEDER OLAM REVISITED – Chronology of the Bible and beyond, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.seder-olam.info/seder-olam-g29-alexander.html

- alexander the great meeting the high priest of jerusalem – NumisWiki, The Collaborative Numismatics Project – FORVM Ancient Coins, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.forumancientcoins.com/numiswiki/view.asp?key=alexander%20the%20great%20meeting%20the%20high%20priest%20of%20jerusalem

- Of Alexander the Great’s Meeting the High-Priest of the Jews at Jerusalem., accessed on April 13, 2025, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/josephus/whiston_alexander_Jerusalem.xhtml

- Josephus on Alexander’s visit to Jerusalem – Livius.org, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.livius.org/sources/content/josephus/jewish-antiquities/alexander-the-great-visits-jerusalem/

- Jaddua – Jewish Virtual Library, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jaddua

- ALEXANDER THE GREAT – JewishEncyclopedia.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/1120-alexander-the-great

- Why Are There No More Prophets? – Chabad.org, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/3898883/jewish/Why-Are-There-No-More-Prophets.htm

- Prophecy in Judaism – Chabad.org, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/5183322/jewish/Prophecy-in-Judaism.htm

- The Lost Art of Prophecy – Aish.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://aish.com/48955796/

- Class 26: Haggai, Zechariah, & Malachi – Sermons | Capitol Hill Baptist, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.capitolhillbaptist.org/sermon/class-26-haggai-zechariah-malachi/

- Who is the last prophet in Judaism? – Mi Yodeya – Stack Exchange, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://judaism.stackexchange.com/questions/17727/who-is-the-last-prophet-in-judaism

- Who were Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi? – BooksnThoughts.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://booksnthoughts.com/who-were-haggai-zechariah-and-malachi/

- Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi: Prophecy in an Age of Uncertainty [Hardcover], accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.judaicaplace.com/haggai-zechariah-and-malachi-prophecy-in-an-age-of-uncertainty-hardcover/9781592644131/

- SEDER ‘OLAM ZUṬA – JewishEncyclopedia.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13378-seder-olam-zuta

- Alexander in Ancient Jewish Literature (Chapter 6) – A History of Alexander the Great in World Culture – Cambridge University Press & Assessment, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/history-of-alexander-the-great-in-world-culture/alexander-in-ancient-jewish-literature/B9D0A7D3339FD87BADC1F3EE16041776

- How do we know prophecy ceased in Israel? – Mi Yodeya – Stack Exchange, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://judaism.stackexchange.com/questions/110993/how-do-we-know-prophecy-ceased-in-israel

- End of Prophecy – Mi Yodeya – Stack Exchange, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://judaism.stackexchange.com/questions/120356/end-of-prophecy

- Seder Olam Rabbah – Wikipedia, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seder_Olam_Rabbah

- SEDER ‘OLAM RABBAH – JewishEncyclopedia.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13377-seder-olam-rabbah

- The Seder Olam – franknelte.net, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.franknelte.net/article.php?article_id=285

- Seder Olam Rabbah – Sefaria, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.sefaria.org/Seder_Olam_Rabbah

- The Hebrew Calendar and its Missing Years- Part One by Reuven Herzog and Benjy Koslowe – Kol Torah, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.koltorah.org/halachah/the-hebrew-calendar-and-its-missing-years-part-one-by-reuven-herzog-and-benjy-koslowe

- The Discrepancy Between the Rabbinic and Secular Dates – Chabad.org, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/2836156/jewish/The-Discrepancy-Between-the-Rabbinic-and-Secular-Dates.htm

- Missing years (Jewish calendar) – Wikipedia, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Missing_years_(Jewish_calendar)

- Seder Olam Rabbah modern Jewish calendar English pdf free online – Bible.ca, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.bible.ca/manuscripts/Seder-Olam-Rabbah-full-text-PDF-Free-Online-Chronology-modern-Jewish-calendar-Textual-variants-Bible-manuscripts-Old-Testament-Torah-Tanakh-Rabbinical-Judaism-160AD.htm

- The Missing Two Hundred Years and the Historical Veracity of Hazal – Kol Hamevaser, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://kolhamevaser.com/2016/11/the-missing-two-hundred-years-and-the-historical-veracity-of-hazal/

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 11.304-12.0 – Lexundria, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://lexundria.com/j_aj/11.304-12.0/

- Josephus on Alexander the Great and the Book of Daniel – Jim Hamilton, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://jimhamilton.info/2010/11/26/josephus-on-alexander-the-great-and-the-book-of-daniel/

- Jews & Alexander the Great in Bible Prophecy – Defender’s Voice, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://doctorpaul.org/jews-alexander-the-great-in-bible-prophecy/

- The Jewish Prophesy of Alexander the Great – GreekReporter.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://greekreporter.com/2025/01/19/jewish-prophesy-alexander-the-great/

- Antiquities of the Jews, Book XII – Josephus, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/josephus/ant-12.html

- Alexander the Great and Jaddus the High Priest According to Josephus | AJS Review, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ajs-review/article/alexander-the-great-and-jaddus-the-high-priest-according-to-josephus/8ED923F6BCA859439FDF063D2C4CD12B

- Mythological History, Identity Formation, and the Many Faces of Alexander the Great James Mayer – Monmouth College, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.monmouthcollege.edu/live/files/709-mjur-i01-2011-2-mayerpdf

- Alexander in the Jewish tradition: From Second TempleWritings to Hebrew AlexanderRomances – Brill, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004359932/BP000017.pdf

- Kislev II – Stevens Institute of Technology, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://web.stevens.edu/golem/llevine/rsrh/hellenism_judaism.pdf

- HELLENISM – JewishEncyclopedia.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7535-hellenism

- Is Hanukkah Prophetic? Foreshadowing Victory in the End Times — FIRM Israel, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://firmisrael.org/learn/is-hanukkah-prophetic/

- Eschatology – Jewish Beliefs, Messianism, Afterlife | Britannica, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/eschatology/Judaism

- CHAPTER 4 The End of Prophecy? – The Mystic Heart of Judaism – RSSB, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://rssb.org/the-mystic-heart-of-judaism10.html

- Man vs. Prophecy? A New Look at the Classic Discussion of Predetermination in the Izhbitz School | The Lehrhaus, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://thelehrhaus.com/commentary/man-vs-prophecy-a-new-look-at-the-classic-discussion-of-predetermination-in-the-izhbitz-school/

- The End of Prophecy – www2.goshen.edu, accessed on April 13, 2025, http://www2.goshen.edu/~joannab/prophets/cessation.html

- The closed canon—what are the implications? | GotQuestions.org, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.gotquestions.org/closed-canon.html

- Development of the Hebrew Bible canon – Wikipedia, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Development_of_the_Hebrew_Bible_canon

- The Close of the Old Testament Canon – Olsen Park church of Christ, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://olsenpark.com/Bulletins17/FS19.16.html

- The Closing Of The Old Testament Canon – Alpha and Omega Ministries, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.aomin.org/aoblog/roman-catholicism/the-closing-of-the-old-testament-canon/

- The cessation of Jewish prophecy : r/AcademicBiblical – Reddit, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/AcademicBiblical/comments/dv8c4o/the_cessation_of_jewish_prophecy/

- The Anticipated Closing of the Canon | Biblical Blueprints, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://biblicalblueprints.com/Sermons/New%20Testament/Revelation/Revelation%2010/Revelation%2010_1-11,%20part%204

- Cessationism – Tabletalk Magazine, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://tabletalkmagazine.com/article/2020/04/cessationism/

- A Brief Case for Cessationism – The Reformed Classicalist, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.reformedclassicalist.com/home/cessationism

- Protestantism’s Old Testament Problem | Catholic Answers Magazine, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.catholic.com/magazine/print-edition/protestantisms-old-testament-problem

- A Sage is Greater than a Prophet | Shoftim | Covenant & Conversation | The Rabbi Sacks Legacy, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://rabbisacks.org/covenant-conversation/shoftim/a-sage-is-greater-than-a-prophet/

- Prophets and Sages – Reconstructing Judaism, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.reconstructingjudaism.org/dvar-torah/prophets-and-sages/

- A Sage is Greater than a Prophet | Shoftim | Covenant & Conversation Family Edition | The Rabbi Sacks Legacy, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://rabbisacks.org/covenant-conversation-family-edition/shoftim/a-sage-is-greater-than-a-prophet/

- A Sage is Greater than a Prophet – Aish.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://aish.com/a-sage-is-greater-than-a-prophet/

- CHAPTER 5 Sages and Rabbis – The Mystic Heart of Judaism – RSSB, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://rssb.org/the-mystic-heart-of-judaism11.html

- ON PROVIDENCE AND PROPHECY At the closure of Halakhic Man, R. Soloveitchik deals at length with the peaks of creativity – Brill, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://brill.com/downloadpdf/book/9789047419990/Bej.9789004157668.i-376_015.xml

- Bat Kol | Encyclopedia.com, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/bat-kol

- Some Aspects of the Holy Spirit in early Judaism, accessed on April 13, 2025, http://archive.hsscol.org.hk/Archive/periodical/abstract/A019f.htm

- Bat Kol: A Divine Voice | My Jewish Learning, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/bat-kol-a-divine-voice/

- Tag: bat kol – The Back of My Mind, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://gpront.blog/tag/bat-kol/

- Voice of God – Wikipedia, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voice_of_God

- Rabbi Sacks’ Religious Pluralism: A Halakhic and Hashkafic Defense – Torah Musings, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.torahmusings.com/2022/11/rabbi-sacks-religious-pluralism-a-halakhic-and-hashkafic-defense/

- Historicist interpretations of the Book of Revelation – Wikipedia, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historicist_interpretations_of_the_Book_of_Revelation

- On the Question of the »Cessation of Prophecy« in Ancient Judaism – Mohr Siebeck, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.mohrsiebeck.com/en/book/on-the-question-of-the-cessation-of-prophecy-in-ancient-judaism-9783161509209/

- Prophecy and the prophetic as aspects of Paul’s theology, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2413-94672018000200010

- ‘Cessation of Prophecy’ in Ancient Judaism (Cook) – Enoch Seminar, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://enochseminar.org/8538-2/

- Embodying God’s Final Word: Understanding the Dynamics of Prophecy in the the Ancient Near East and Early Monotheistic Tradi – Digital Commons @ UConn – University of Connecticut, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=usp_projects

- The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls – Scholars Crossing, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1028&context=jlbts

- Messianic Hopes in the Qumran Writings – BYU ScholarsArchive, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/context/mi/article/1047/filename/5/type/additional/viewcontent/Messianic_Hopes_in_the_Qumran_Writings.pdf

- BrookeAbstract – Orion Center for the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls, accessed on April 13, 2025, http://orion.mscc.huji.ac.il/symposiums/9th/papers/BrookePaper.html

- Prophets and Prophecy in the Qumran Community1 | AJS Review | Cambridge Core, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ajs-review/article/prophets-and-prophecy-in-the-qumran-community1/45D93F6B734C6E13501D2C82A0417CCF

- “When Did Prophecy Cease, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://oru.edu/pdfs/academics/cimes/When%20Did%20Prophecy%20Cease.pdf

- Is cessationism biblical? What is a cessationist? | GotQuestions.org, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://www.gotquestions.org/cessationism.html

- The Cessation of Prophecy in SecondTemple Judaism: Previous Scholarship and a New Proposal – Brill, accessed on April 13, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004522022/BP000007.pdf