1. Introduction

The relationship between Jewish intellectual and mystical traditions, particularly Kabbalah, and the development of Western science and rationality presents a complex, historically layered, and vigorously debated field of inquiry.1 It is a narrative marked by intricate intersections, mutual influences, appropriations, tensions, and outright rejections across diverse historical epochs and intellectual milieus.2 This report aims to synthesize a range of scholarly perspectives, drawn from the provided sources, to illuminate the multifaceted nature of this engagement. It will explore the arguments concerning the indirect cultural and philosophical contributions of Jewish thought to the foundations of scientific rationality, delve into the historical participation of Jews in scientific endeavors and the ongoing debate surrounding the direct influence of Jewish religious concepts on scientific discovery, define the core tenets and concepts of Kabbalah, examine its historical encounters with early modern science, analyze potential conceptual resonances and dissonances between Kabbalistic frameworks and scientific paradigms, and survey the spectrum of scholarly opinions on these complex connections.

It is crucial at the outset to acknowledge the inherent complexity and resist monolithic interpretations. The interaction between Jewish thought and science is not a straightforward tale of conflict or harmony but involves a dynamic interplay across centuries.4 Furthermore, “Jewish thought” itself is not a singular entity but encompasses a vast and often contradictory range of philosophical, legal, and mystical perspectives developed by Jews throughout history.4 Distinguishing between thinking by Jews, which has undeniably contributed significantly to science, and the influence of specific Jewish religious or theological ideas on the content or method of science is essential for analytical clarity.4 This analysis necessitates an interdisciplinary approach, drawing upon insights from the history of science, philosophy of religion, theology, and Jewish studies to navigate the entangled paths of faith, reason, mysticism, and empirical inquiry.2 This report will proceed by examining potential indirect influences, tracing historical engagement, defining Kabbalah, exploring its specific historical and conceptual links to science, summarizing the scholarly debate, and offering concluding reflections on this enduring and intricate relationship.

2. Jewish Thought and the Seeds of Rationality: Indirect Influences on Science

A significant line of argument, prominently associated with the sociologist Max Weber but echoed by various thinkers, posits that certain foundational elements within Jewish thought, while not directly contributing theological content to scientific theories, cultivated an intellectual and cultural environment conducive to the emergence of Western rationality, a necessary precursor to modern science.4 This perspective suggests an indirect, yet potentially profound, influence operating through core worldview assumptions and cultural values. However, this remains a contested area, with other scholars questioning the uniqueness or direct impact of these factors.4

Demythologization and a Lawful Universe

Central to this argument is Weber’s assertion that the opening chapter of Genesis constitutes a revolutionary act of demythologizing the universe.4 By portraying the cosmos not as the playground of capricious and often conflicting deities, but as the deliberate creation of a single, transcendent God, Judaism stripped nature of its mythical and magical dimensions. The sun, moon, and stars were not gods to be worshipped, but creations serving divine purposes. This conceptual shift, according to Weber, allowed the universe to be perceived “for what it was”—an ordered realm governed by consistent principles rather than unpredictable divine whims.4 This perception of a world operating under divine law laid the groundwork for seeing it as potentially understandable through rational inquiry. This aligns with the Jewish theological understanding that God established the natural laws governing the world.7 The concept of a single Creator implies a unified, coherent system, contrasting sharply with polytheistic views where nature might be subject to arbitrary interventions by multiple powers.4

Intelligibility of Creation (Ḥokhma/Wisdom)

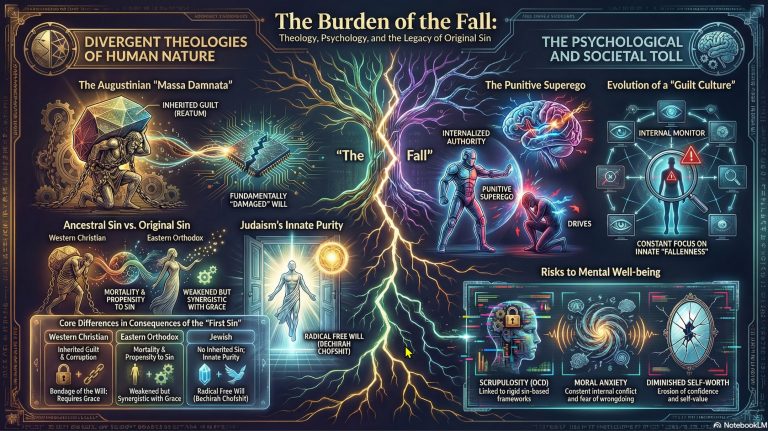

Complementing the idea of a lawful universe is the deep-seated Jewish emphasis on creation as a product of divine wisdom (Hebrew: Ḥokhma).4 If the universe is God’s handiwork, imbued with His wisdom, then it must be inherently rational, ordered, and intelligible. This belief fosters the conviction that the world makes sense and its workings can, in principle, be grasped by the human mind through reason and observation.4 This contrasts with views that might see the ultimate nature of reality as fundamentally chaotic or beyond human comprehension. The philosopher Moses Maimonides (1138-1204) famously articulated the view that the study of the natural world—essentially, science—is not only permissible but constitutes a path towards the love and fear (awe) of God, as it reveals the intricacies of His creation.3 The very intelligibility of the cosmos invites human investigation. Some extend this to suggest an expectation that scientific discoveries will ultimately align with or parallel core biblical claims, reflecting a belief in a unified truth accessible through both revelation and rational inquiry.4

The Value of Questioning and Debate

Jewish intellectual culture places a remarkable premium on questioning, argumentation, and debate.4 The Talmudic tradition, with its intricate dialectics and recording of minority opinions, exemplifies this ethos.8 The practice of havruta, paired study involving rigorous discussion and challenge, further institutionalizes this approach.4 Even foundational rituals like the Passover Seder mandate the asking of questions at the outset.4 This cultural “almost-obsession” with inquiry fosters critical thinking, challenges complacency and dogma, and cultivates intellectual habits essential for scientific progress, which inherently relies on questioning existing knowledge and proposing alternative explanations.4 Indeed, some argue that the entirety of Jewish civilization is predicated on constant internal debate.4

Iconoclasm and Challenging Norms

The Jewish tradition traces its origins to Abraham, portrayed as an iconoclast who challenged the prevailing idolatry of his time.4 This foundational narrative, coupled with the biblical prohibition against idolatry (Bilderverbot) 2, may cultivate a predisposition towards challenging established norms, conventions, and authorities – both religious and intellectual.4 This iconoclastic spirit resonates with the scientific endeavor, which often requires breaking from established paradigms and questioning deeply entrenched assumptions to achieve breakthroughs.4 The rejection of concrete representations of the divine might also have encouraged abstract modes of thought, a capacity vital for theoretical science.2

Partnership with God (Tikkun Olam)

Jewish thought often conceives of humanity as having an active role, as “partners with God,” in the ongoing process of creation and the perfection or repair of the world (Tikkun Olam).4 This contrasts with theological frameworks that might view human intervention in nature with suspicion, as “playing God.” The Jewish perspective, instead, can be interpreted as providing a positive mandate for human engagement with the world, including understanding its workings (science) and improving it (technology and medicine).4 This proactive stance towards the created order can be seen as theologically supportive of scientific exploration and application.

Democratization of Learning and Innovation (Chiddush)

Historically, Jewish culture has placed a strong emphasis on learning, literacy, and intellectual pursuits, traditionally centered on sacred texts like the Torah and Talmud.4 This reverence for study extended, in principle, across social strata, with traditions supporting the education even of the poor.4 Beyond mere learning, Jewish tradition also values chiddush—innovation or novel interpretation.4 While seemingly paradoxical within a tradition-bound framework, the Talmudic saying, “Whatever an earnest scholar will someday teach has already been spoken to Moses at Sinai,” can be interpreted as sanctifying intellectual creativity, framing even radical new insights as deeper understandings of the original revelation.4 This fostered a competitive intellectual environment where scholars vied to produce insightful chiddushim, potentially cultivating a mindset receptive to novelty and progress applicable beyond purely textual study.4

Contrasting Views and Nuances

These arguments for indirect influence are not universally accepted. Critics contend that attributing Jewish success in science specifically to religious thought is problematic.4 They argue that the emphasis on rationality and logic, while present, is not unique to Judaism.4 Furthermore, the concept of “Jewish thinking” is itself questionable, given the vast internal diversity and contradictions within Jewish philosophical and mystical traditions.4 Alternative explanations focus on socio-historical factors: the high cultural value placed on learning in general (not specifically scientific learning) 4; historical restrictions that pushed Jews into professions like medicine and finance, and later science, where barriers might have been lower 4; and the embrace of science by secularizing Jews in the modern era as a vehicle for social integration, assimilation, and participation in Enlightenment values like meritocracy and universalism.4 Some scholars maintain a strict separation between the domains of science (reason, experience) and religion (revelation, faith), arguing that theology, by its nature, cannot directly influence scientific methodology or discovery.4

The very nature of the rationality potentially fostered by Jewish tradition warrants closer examination. While emphasizing logic and questioning 4, Jewish intellectual history is equally marked by profound reverence for received texts and tradition.4 The concept of chiddush, or innovation, operates primarily within the framework of interpreting and reinterpreting these foundational texts.4 This suggests that the “rationality” cultivated might be a specific kind – a dialectical rationality, sharpened through centuries of legal and textual analysis, debate, and the reconciliation of apparent contradictions within an authoritative corpus. This model, where novelty emerges through re-engagement with tradition, differs from a purely empirical or post-Enlightenment scientific rationality. While such dialectical skills could undoubtedly foster rigorous analysis applicable to scientific problems, the underlying deference to foundational texts could, in other contexts, potentially act as a constraint on challenging fundamental premises derived from those texts. Therefore, the contribution may lie less in “rationality” itself and more in the cultivation of specific analytical and interpretive skills born from a unique intellectual tradition balancing reason and revelation.

3. Jewish Engagement with Science Through History: Direct Influence and Participation

Moving beyond arguments about indirect cultural predispositions, the historical record reveals significant engagement by Jews with scientific activities across different periods. This section examines this participation, particularly the crucial role played during the Middle Ages, and addresses the more contentious debate regarding any direct influence of Jewish religious or theological concepts on the methods or findings of scientific inquiry.

Medieval Contributions: Translation and Transmission

The Middle Ages witnessed Jewish scholars playing an indispensable role as cultural and linguistic intermediaries, particularly in the transmission of scientific and philosophical knowledge.17 Initially centered in the Abbasid Caliphate (Baghdad, 8th-9th centuries), Jewish figures like Masarjuwayh of Basra were among the earliest translators of Greek and Syriac medical texts into Arabic.17 Isaac Israeli (Isaac Judaeus) was a notable early medical author whose Arabic works reached Europe.17

This role became even more pronounced in Islamic Spain (Al-Andalus). Jewish intellectuals, fluent in Arabic, Hebrew, and often Latin or vernacular languages, actively participated in the vibrant intellectual life, writing scientific treatises primarily in Arabic, which they helped establish as a language of science.17 Hisdai ibn Shaprut, a 10th-century physician and community leader, exemplifies this, contributing to the Arabic version of Dioscorides’ Materia Medica.17

As intellectual openness waned in the Islamic world under stricter orthodoxies (Almoravids, Almohads), and the Latin West began its rediscovery of classical learning, Jewish translators became crucial conduits.17 Working in centers like Toledo (Spain) and Provence (Southern France), they translated a vast corpus of Arabic works—encompassing philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, physics, geography, cosmology, and even astrology and magic—into Latin, Spanish, and French.17 This transmission of Greek knowledge, preserved and augmented by Islamic scholars, provided foundational material for the development of science in medieval and early modern Europe.17 Their contributions extended to practical sciences, including the development of instruments for measurement, cartography, and navigation, vital for exploration and astronomy.17 Concurrently, from the 12th century onwards, Hebrew increasingly became a language for Jewish scientific writing, with original works and translations from Arabic and Latin being produced in Hebrew by scholars like Abraham ibn Ezra and Abraham bar Hiyya.17

Medieval Contributions: Original Work and Philosophical Integration

Beyond translation, medieval Jewish thinkers made original contributions and engaged deeply with the scientific and philosophical currents of their time, primarily Aristotelianism as mediated through Islamic philosophers like Avicenna and Averroes.15 Figures such as Maimonides, Levi ben Gershom (Gersonides), Hasdai Crescas, and Isaac Albalag grappled with reconciling the tenets of Jewish faith with regnant scientific and philosophical views.15

A central tension explored in medieval Jewish philosophy was the relationship between reason (derived from philosophy and science) and revelation (derived from the Torah and tradition).15 Rationalists like Maimonides viewed science and philosophy not as threats, but as compatible paths to understanding divine wisdom.3 He famously stated that if science were to definitively prove a concept (like the eternity of the world, which he ultimately rejected on philosophical grounds) that contradicted a literal reading of scripture but not a fundamental article of faith, he would reinterpret the scripture accordingly.3 For Maimonides, studying God’s creation through science was a religious imperative.3 Gersonides similarly engaged deeply with Aristotelian science, sometimes modifying philosophical positions to align with theological commitments, such as adopting a specific view of time (a “growing block” theory where the future does not yet exist) to preserve human free will against divine foreknowledge.16

Scientific knowledge was also applied within Jewish legal practice (Halakha). Astronomical calculations were essential for establishing the complex Jewish calendar, an activity the Talmud viewed as reflecting divine wisdom.3 However, the reliance on contemporary scientific understanding sometimes led to challenges. The Talmud contains statements based on the science of its time that were later proven incorrect (e.g., regarding the viability of certain premature infants or the spontaneous generation of lice).3 This created debates among later authorities about whether Halakha based on outdated science should be revised or maintained out of deference to tradition.3 It is important to note the diversity within medieval Jewish thought, which included mystical schools alongside rationalist ones, often in dialogue or tension.8 Furthermore, despite the rationalist embrace of science by figures like Maimonides, by the 13th and 14th centuries, a growing suspicion towards philosophy and science emerged in some segments of the Jewish community.17

Early Modern Period and Beyond

The modern era has seen remarkable contributions by Jewish individuals to science, statistically disproportionate to their percentage of the world population.11 This includes numerous Nobel laureates and foundational figures across physics, medicine, chemistry, and other fields, such as Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Jonas Salk, and Robert Oppenheimer.20 However, this prominence largely coincided with Jewish emancipation and integration into broader European society, as they were generally outside the scientific mainstream in earlier centuries.4 The Italian Renaissance marked an early point of increased contact between Jewish and Christian scholars.4

The reasons for this modern scientific flourishing remain debated. As discussed earlier, explanations range from cultural factors inherent in Jewish tradition (value on learning, intellectual rigor) to socio-historical circumstances (patterns of immigration, overcoming discrimination, secularization trends where science offered a path to modernity and universalism).4

The Debate on Direct Theological Influence

The question of whether specific Jewish religious or theological doctrines have exerted a direct influence on scientific methodology or discovery is highly contested. The predominant view among many scholars and scientists is skeptical.4 Arguments against direct influence often emphasize the distinct epistemological foundations of science (empirical observation, reason, testability) and religion (revelation, faith, sacred texts).3 From this perspective, religious beliefs belong to the realm of theology or metaphysics and do not, or should not, impinge upon the objective methods of scientific inquiry.4 It is argued that the research agendas of modern Jewish scientists are shaped by the norms and questions of the international scientific community, not by specific tenets of Jewish theology.4

However, alternative perspectives exist. Some scholars suggest that religious background assumptions can subtly shape scientific interpretations, citing potential examples like the influence of theological ideas of predestination on certain historical interpretations within evolutionary biology.22 Others focus on the compatibility between core Jewish beliefs (e.g., a Creator who established rational natural laws) and the findings of modern science (e.g., the Big Bang, the lawfulness of the cosmos, even the factual aspects of evolution).4 Maimonides’ framework, where understanding God’s creation is a religious goal, could be seen as providing a theological motivation for scientific work, even if not dictating its methods or conclusions.3 The recurring theme in Jewish responses to apparent conflicts between science and tradition is often not outright rejection of science, but an assertion that the conflict stems from either incomplete scientific understanding or, more commonly, a misinterpretation of the religious texts, which allows for reconciliation.3

When evaluating the historical engagement, a critical distinction emerges. The historical participation of Jews in scientific activity, particularly their vital role in the transmission and preservation of knowledge during the Middle Ages, is well-documented and broadly acknowledged.17 This intermediary function, facilitated by linguistic skills and unique socio-historical positioning, was undeniably significant for the trajectory of Western science. However, this role is distinct from demonstrating a direct causal influence of specific Jewish theological doctrines on the content or methodology of scientific discovery itself. While figures like Maimonides sought synthesis, claims that Jewish theology drove specific scientific breakthroughs are far more speculative and less consistently supported by the available evidence than the well-established transmission narrative.4 Often, arguments for direct influence conflate the existence of cultural values potentially conducive to science (like valuing learning or questioning) with evidence that religious doctrines directly shaped scientific practice. The historical weight of Jewish contribution appears more robustly in the facilitation of knowledge flow across cultures than in the theological shaping of scientific methods or theories.

4. Kabbalah: Defining the Mystical Tradition

Within the diverse landscape of Jewish thought, Kabbalah represents the major tradition of mysticism and esotericism, offering interpretations of God’s essence, the nature of reality, and humanity’s place within the cosmos that often diverge from purely rationalist philosophical approaches.24 Understanding its core concepts is essential before examining its potential interactions with science.

Definition and Scope

Kabbalah (Hebrew: קַבָּלָה, Qabbālā), literally meaning “reception” or “tradition,” denotes an esoteric method, discipline, and school of thought focused on the mystical interpretation of Jewish tradition.25 It seeks to penetrate the inner, hidden meaning (Nistar) of the Hebrew Bible and rabbinic literature, exploring the nature of the divine and the secrets of creation.24 While mystical currents existed earlier in Judaism (e.g., Merkabah mysticism focused on heavenly ascents) 25, modern scholarship typically reserves the term “Kabbalah” for the specific theosophical and theological doctrines that emerged textually in 12th-13th century Provence (Southern France) and Spain, with foundational texts like Sefer ha-Bahir (Book of Illumination) and Sefer ha-Zohar (Book of Splendor).25 It experienced a major renaissance in 16th-century Safed (Ottoman Palestine), particularly through the complex system of Isaac Luria (the Ari).25 While academically distinct, in popular usage “Kabbalah” often serves as a catch-all term for all forms of Jewish esotericism.24 It stands in contrast, though sometimes in dialogue, with rationalist Jewish philosophy, particularly Maimonidean Aristotelianism.16

Core Tenets and Goals

Kabbalah encompasses several interrelated dimensions:

- Theosophical/Theoretical: Seeking to understand and describe the structure and dynamics of the divine realm, often using symbolic and mythic language drawn from human psychological experience.25 This involves mapping the emanations of the Godhead (the Sefirot) and their interactions.25

- Experiential/Ecstatic: Aiming for direct, intuitive, unmediated encounters with the divine, often described as Devekut (cleaving or attaching to God) or mystical union.10 This involves disciplined spiritual practices, though typically integrated within communal Jewish life rather than monasticism.24

- Theurgic/Practical: Believing that human actions, particularly the performance of mitzvot (commandments) with proper intention (kavvanah), can directly influence and affect the divine realms, either harmonizing or disrupting the flow of divine energy.25 This connects to the idea of Tikkun Olam (repair of the world), where humans play a crucial role in restoring cosmic harmony.10 Practical Kabbalah also includes, more controversially, rituals involving divine names or angelic forces to effect change in the world, often viewed with caution by Kabbalists themselves.24

A central theme is the desire for intimacy with God, often stemming from a belief in a profound kinship or continuum between the Creator and Creation, with a hidden spark of divinity residing within each individual and, indeed, all existence.24

Key Cosmological and Metaphysical Concepts

Kabbalistic cosmology and metaphysics are built around several key concepts:

- Ein Sof (אין סוף): Meaning “Without End” or “Infinite,” this refers to the absolute, transcendent, unknowable essence of God beyond all description, limitation, or conception. It is the ultimate divine reality from which all else emerges.10

- Tzimtzum (צמצום): Primarily a Lurianic concept, this denotes the paradoxical “contraction” or “withdrawal” of the infinite Ein Sof into itself, creating a conceptual “void” or “space” (makom panui) wherein finite creation could emerge. This addresses the problem of how a finite, differentiated world could arise from an undifferentiated infinity.10

- Sefirot (ספירות): These are the ten fundamental attributes, emanations, dimensions, or vessels of divine energy through which Ein Sof manifests and interacts with creation.10 They are not God’s essence (Ein Sof) but His unfolding powers and modes of action. They constitute a dynamic, stratified structure, often depicted visually as the Ilan (Tree of Life) with three columns, or as a series of concentric spheres.6 The ten Sefirot, typically listed from highest to lowest, are: Keter (Crown), Chokhmah (Wisdom), Binah (Understanding), Chesed (Loving-kindness/Mercy) or Gedulah (Greatness), Gevurah (Strength/Judgment) or Din (Judgment), Tiferet (Beauty/Glory), Netzach (Victory/Endurance), Hod (Splendor/Majesty), Yesod (Foundation), and Malkhut (Kingdom/Shekhinah).6 They represent the core structure of divine emanation.35

- Emanation (Atzilut): Creation in Kabbalah is generally understood not as creatio ex nihilo (creation from nothing) in the absolute philosophical sense, but as a process of emanation or unfolding (hishtalshelut) where divinity flows outward from Ein Sof through the Sefirot, progressively becoming more differentiated and seemingly less divine at lower levels.10 Kabbalah reinterprets creatio ex nihilo by positing Ayin (Nothingness) – often identified with the highest Sefirah, Keter, or even Ein Sof itself – as the paradoxical source from which Yesh (Being/Something) emerges.30

- Shevirat ha-Kelim (שבירת הכלים): The “Shattering of the Vessels,” a central doctrine in Lurianic Kabbalah. It describes a cosmic catastrophe during the process of emanation where the lower seven Sefirotic vessels were unable to contain the intense divine light flowing into them and consequently shattered. This resulted in the scattering of divine sparks (nitzotzot) throughout the lower realms, mingling with the shards (kelipot, husks or shells, associated with evil), creating a state of cosmic exile and imperfection.10

- Tikkun Olam (תיקון עולם): The “Repair” or “Rectification of the World.” Following the Shevirah, the primary task of humanity, particularly through the observance of mitzvot with Kabbalistic intention, is to gather the fallen divine sparks, separate them from the kelipot, and restore them to their divine source, thereby mending the fractured cosmos and facilitating the reunification of the Sefirot.10

- Four Worlds (ארבע עולמות): Kabbalah posits four primary levels or worlds of existence, representing descending stages of emanation and increasing concealment of divinity: Atzilut (World of Emanation, purely divine), Beriah (World of Creation, archangelic), Yetzirah (World of Formation, angelic), and Assiah (World of Action/Making, physical world and lower spiritual forces).10 These worlds also correspond to levels of the soul and layers of scriptural interpretation.

- Cosmology: Kabbalistic descriptions of the cosmos often integrate elements from contemporary scientific models (e.g., Ptolemaic geocentric system of nested spheres) but reinterpret them symbolically to represent the Sefirot or spiritual hierarchies.29 The Sefirot themselves were frequently visualized as concentric spheres, reflecting the astronomical understanding of the time.29

Epistemology (Ways of Knowing)

Kabbalah’s epistemology differs significantly from that of empirical science or rationalist philosophy. It prioritizes access to hidden, esoteric knowledge (Nistar).24 Key methods include:

- Textual Interpretation: Deep, often non-literal interpretation of sacred texts (Torah, Zohar, etc.), employing hermeneutical techniques like Gematria (calculating numerical equivalents of Hebrew letters/words), Notarikon (interpreting words as acronyms), and Temurah (permuting letters) to uncover concealed meanings.10

- Oral Tradition: Transmission of secret knowledge from master (rav or rebbe) to disciple (talmid).24

- Mystical Experience: Direct revelation, prophetic insight, visionary states, or ecstatic experiences are considered valid, even superior, sources of knowledge about the divine and the true nature of reality.24 Mystics seek to “taste the whole wheat of spirit before it is ground by the millstones of reason”.24

While often contrasted with rationalism due to its emphasis on supra-rational experience and revelation 19, Kabbalah is not devoid of intellectual structure. Kabbalists developed intricate, highly systematic doctrines and logical frameworks to articulate their understanding of the divine and the cosmos.13 Thinkers like Lazar Gulkowitsch studied the rational elements and systematic nature inherent within Kabbalistic and Hasidic thought, seeing them as attempts to build logical systems, albeit ones aware of the limits of rationality when confronting the divine.13 The elaborate structures of the Sefirot, the Four Worlds, the detailed processes of emanation and Tikkun, and the use of diagrams all point to a profound effort to create a coherent, internally consistent, albeit esoteric, body of knowledge.6 This suggests that the common dichotomy between “rationalist” philosophy and “mystical” Kabbalah 16 might obscure the complex internal logic and systematic aspirations within Kabbalah itself. It represents not simply an irrational flight from reason, but an alternative, highly structured system for comprehending reality, grounded in different epistemological premises. Recognizing this internal systematicity is crucial for appreciating its potential points of contact and divergence with scientific modes of thought.

5. Kabbalah and Early Modern Science: Historical Encounters

The Renaissance and early modern period (roughly 15th-17th centuries) witnessed a fascinating, though complex and often indirect, encounter between Kabbalistic ideas and the burgeoning scientific thought of Europe. This era saw Kabbalah move beyond exclusively Jewish circles, influencing Christian intellectuals and becoming intertwined with other esoteric currents like Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, and natural magic, all contributing to the intellectual ferment from which modern science emerged. Assessing the precise impact of Kabbalah requires careful navigation of scholarly debates and the transformations ideas underwent as they crossed cultural boundaries.

Christian Cabala and the Renaissance

The introduction of Kabbalah into Christian intellectual circles was largely initiated by the Italian Renaissance philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494).31 Pico, driven by a syncretic impulse, sought to harmonize various philosophical and religious traditions—including Platonism, Aristotelianism, Hermeticism, and Christianity—into a unified system representing a prisca theologia, an ancient, universal wisdom.31 He encountered Kabbalah, likely through Jewish converts like Flavius Mithridates who served as his teacher and translator, and became convinced that it represented the secret, oral tradition given to Moses alongside the written Torah, containing profound truths that, he believed, confirmed Christian doctrines, particularly the divinity of Christ.31 His famous 900 Theses, proposed for public debate in Rome in 1486, included numerous propositions drawn from Kabbalistic sources.41

Pico’s enthusiasm sparked the movement known as Christian Cabala (the distinct spelling often differentiates it from Jewish Kabbalah).31 Figures like Johannes Reuchlin in Germany, Francesco Giorgi (Zorzi) in Venice, and later Agrippa von Nettesheim and others, embraced Cabala, integrating its concepts (like the Sefirot, divine names, and interpretive methods) into Christian theological and cosmological frameworks.39 However, it is crucial to recognize that this adoption was highly selective and transformative. Christian Cabalists often misunderstood or deliberately reinterpreted Jewish Kabbalah to fit their own theological agendas, frequently employing it polemically to argue for Jewish conversion.38 The tradition was also admixed with spurious or pseudo-Kabbalistic texts.38

During this period, interest in Kabbalah often overlapped with fascination in natural magic, alchemy, and Hermeticism (texts attributed to the mythical Hermes Trismegistus).31 These traditions shared a view of the cosmos as an interconnected web of hidden correspondences and forces, potentially accessible and manipulable through esoteric knowledge, mathematics, and ritual.43 Thinkers like Marsilio Ficino (Pico’s mentor), Agrippa, and Giordano Bruno explored these connections, contributing to a worldview where the boundaries between science, magic, and mysticism were fluid.42

Kabbalah, Mysticism, and the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries unfolded against this backdrop where esoteric and mystical ideas circulated widely and often informed the work of natural philosophers.43 Science, as practiced then, frequently incorporated elements of alchemy, astrology, and theology that would later be purged.1

Some historians and commentators argue that the dissemination of Kabbalistic ideas, facilitated by Latin translations of texts like the Zohar and the works of Christian Cabalists, contributed positively to the intellectual climate that fostered the Scientific Revolution.44 Specific claims include that Kabbalah reinforced a view of the universe as orderly, governed by consistent rules, and intelligible—a universe where phenomena occur for reasons that can potentially be discovered.44 The Kabbalistic emphasis on hidden structures underlying reality and the potential use of mathematical relationships (like Gematria) might also be seen by some as resonating with the increasing mathematization of nature, a hallmark of the new science 43, although Neoplatonism and Pythagoreanism are more commonly cited direct influences here.43

Assessing the influence on key figures remains complex:

- Isaac Newton (1643–1727): Newton devoted enormous intellectual energy to theology, biblical interpretation, chronology, and alchemy, alongside his groundbreaking work in physics and mathematics.45 His unpublished theological manuscripts reveal profound engagement with ancient history and scripture, driven by a desire to recover the original, pure monotheistic religion (prisca theologia) which he believed had been corrupted, particularly by the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, which he rejected as idolatrous.45 In this quest, he consulted a wide range of sources, including Jewish texts like the works of Maimonides, the Talmud, and Kabbalistic writings available in Latin translation.45 He believed ancient sages, including Moses, possessed profound scientific knowledge, encoded symbolically in structures like the Tabernacle and Solomon’s Temple, which he saw as models of the cosmos.44 However, despite his interest and use of these sources, the scholarly consensus is that Newton was not a “Christian Kabbalist”.45 His interest was highly idiosyncratic, subordinated to his own anti-Trinitarian theological project and his search for historical evidence of the original religion. While his worldview allowed for divine action, his published natural philosophy largely adhered to seeking naturalistic explanations.1 His extensive theological and alchemical work remained largely hidden during his lifetime.45 Resources for studying his manuscripts are available.47

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716): Leibniz, a polymath with vast interests in philosophy, mathematics, theology, and diplomacy, maintained a lifelong commitment to intellectual reconciliation (irenicism) and finding unifying truths across different systems.49 The influence of Kabbalah on his philosophy is a subject of ongoing scholarly debate. The traditional view largely discounted any significant impact.53 However, historian Allison Coudert, based on manuscript evidence of Leibniz’s close interactions and correspondence with leading Christian Kabbalists Francis Mercury van Helmont and Christian Knorr von Rosenroth (translator of the Kabbala Denudata), argues for a substantial, though often concealed, influence.53 Coudert suggests that recognizing this Kabbalistic context (particularly Lurianic ideas of monism, vitalism, perfectionism, and universal salvation transmitted via Van Helmont) illuminates key Leibnizian doctrines like monads, pre-established harmony, and optimism.53 Others remain skeptical, attributing parallels to shared Christian Platonist roots or Leibniz’s general eclecticism rather than direct Kabbalistic borrowing.51 Leibniz did engage with contemporary discussions involving Kabbalah, such as Johann Georg Wachter’s attempt to link Spinozism and Kabbalah.33 Leibniz’s own philosophy aimed to synthesize modern mechanical philosophy with elements of older traditions (Aristotelian, Platonic, Scholastic) 52, and his theological work sought rational defensibility and practical spiritual benefit.56

Critique and Caution

Investigating these historical connections requires caution against anachronism—projecting modern categories of “science” or “religion” onto the past 11—and necessitates rigorous historical method.47 The significant transformations Kabbalah underwent in Christian hands must be acknowledged; influence was rarely direct transmission but involved selection, reinterpretation, and integration into different intellectual frameworks.38 Distinguishing genuine influence from mere parallel development or shared roots in older traditions (like Neoplatonism) is critical.

The process by which Kabbalistic ideas entered Christian European thought highlights the crucial role of intermediaries and reinterpretation. Figures like Pico did not access Kabbalah directly in its original context but through translators and converts who mediated the tradition.31 Subsequent Christian Cabalists adapted these ideas for their own purposes, often polemically.38 Even when thinkers like Newton or Leibniz engaged with Kabbalistic texts or concepts (often in translation or via Christian interpreters) 45, they did so selectively, embedding these elements within their own unique and pre-existing philosophical and theological systems. This multi-layered process of transmission and transformation means that the “influence” of Kabbalah was typically indirect, filtered, and creatively repurposed. Understanding the specific context, motivations, and frameworks of both the transmitters and the recipients is essential to avoid simplistic claims of direct causality and to appreciate the complex dynamics of intellectual exchange across cultural and religious divides.

6. Conceptual Resonances and Dissonances: Kabbalah and Scientific Frameworks

Beyond historical interactions, analysts have explored potential conceptual parallels, resonances, and dissonances between the frameworks of Kabbalah and those of science, both historical and contemporary. While such comparisons can be intellectually stimulating, they demand significant caution to avoid superficial equation (“concordism”) or the imposition of modern concepts onto historical systems.5 Kabbalah and science operate with fundamentally different epistemologies, goals, and methodologies.7

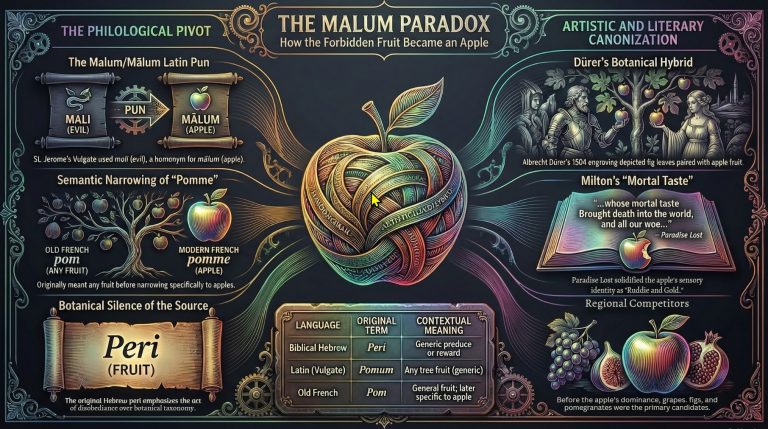

Cosmology and Creation

- Emanation vs. Big Bang: Some popular accounts draw parallels between Kabbalistic creation narratives—involving the infinite Ein Sof, a primordial “contraction” (Tzimtzum), and the emanation of reality through the Sefirot—and the scientific Big Bang theory.4 Similarities cited include a beginning from an initial state of unity or nothingness (Ayin in Kabbalah) and the central role of light/energy in the initial stages.4 However, the differences are profound. Kabbalah describes a teleological, divine process driven by God’s will, involving spiritual entities (Sefirot), and often incorporating cosmic drama (like the Shattering of the Vessels) aimed at ultimate spiritual reunification and repair (Tikkun).10 The Big Bang, within its scientific framework, is a naturalistic, physical model describing the expansion of spacetime from an extremely hot, dense state, governed by physical laws and lacking inherent purpose or divine agency.7 Kabbalistic emanation can be seen as an ongoing process, whereas the Big Bang describes a specific point in cosmic history.

- Age of the Universe: Notably, some Kabbalistic traditions contain concepts that allow for an ancient universe, contrasting with young-earth interpretations based on literal readings of Genesis. The doctrine of Shmitot (cosmic cycles of creation and destruction preceding the current one) was used by medieval Kabbalists like Isaac ben Samuel of Acre (13th century) to calculate the age of the universe in billions of years, reasoning that time before Adam must be measured in vastly longer “divine years”.18 While not scientific calculation, this demonstrates an internal interpretive tradition within Jewish mysticism that accommodated vast timescales long before modern cosmology.

Structure of Reality

- Sefirot and Dimensions (String Theory): A striking, though highly speculative, parallel has been drawn between the ten Sefirot of Kabbalah and the ten spatial dimensions posited in some versions of superstring theory.32 This comparison sometimes extends to mapping the Kabbalistic structure of three “upper” or “intact” Sefirot and seven “lower” or “shattered” Sefirot (in Lurianic thought) onto the three observable spatial dimensions plus seven “compactified” dimensions required by the theory.32 While numerically intriguing, this correlation is generally viewed by scholars as post hoc and lacking deep conceptual grounding.59 The Sefirot are complex theological concepts representing divine attributes and emanations within a rich symbolic and metaphysical system.10 The dimensions of string theory are mathematical constructs within a theoretical physics framework aiming to unify gravity and quantum mechanics. The parallel relies on a numerical coincidence rather than shared methodology or conceptual substance.

- Layered Reality: Kabbalah posits multiple layers of reality (e.g., the Four Worlds of Atzilut, Beriah, Yetzirah, Assiah; the nested structure of the Sefirot) where visible phenomena conceal deeper, more spiritual levels of existence.10 This general idea of a layered reality, where surface diversity hides underlying unity or structure, finds echoes in various scientific and philosophical models, from David Bohm’s physics of implicate and explicate orders to the anthropological structuralism of Claude Lévi-Strauss.59 However, the nature of these layers and, crucially, the methods for accessing and understanding them differ fundamentally: Kabbalah employs mystical intuition, esoteric interpretation, and revelation, while science relies on empirical investigation, mathematical modeling, and logical inference.59

Microcosm/Macrocosm

The idea that the human being (microcosm) reflects the structure of the cosmos or the divine (macrocosm) is prominent in Kabbalah, where the Sefirotic tree is often mapped onto the human body (Adam Kadmon, Primordial Man).6 This concept, however, was widespread in ancient and Renaissance thought, particularly in Neoplatonic and Hermetic traditions that also influenced early science.43 While Kabbalah offers a specific Jewish articulation of this principle, its presence in early science likely draws from these broader philosophical currents as much as, or more than, from Kabbalah directly.

Consciousness and Observation

More recently, some writers have sought connections between Kabbalistic concepts and contemporary scientific and philosophical discussions about consciousness.60 Ideas such as the presence of divine sparks in all things, potential panentheistic interpretations (where God is interwoven with the cosmos) 61, and the general emphasis on the interconnectedness of all reality are sometimes linked to modern theories like panpsychism (the view that consciousness is a fundamental property of matter) or interpretations of quantum mechanics that emphasize the role of the observer in shaping reality.60 These efforts represent contemporary philosophical explorations using Kabbalistic ideas as conceptual resources, rather than claims about historical influence or strict equivalence between the mystical tradition and modern physics or neuroscience.60

Epistemological Chasm

Despite any superficial resonances, the fundamental epistemological divide remains. Kabbalah ultimately grounds its knowledge in divine revelation, mystical experience, and the interpretation of sacred texts believed to hold hidden, divine meaning.24 Science, conversely, bases its claims on empirical evidence, logical reasoning, mathematical consistency, and falsifiability through experiment and observation.3 Their goals also differ: Kabbalah seeks spiritual enlightenment, intimacy with God, and cosmic repair; science aims to describe, explain, predict, and sometimes control natural phenomena.

The persistent attempts to draw parallels between Kabbalistic concepts and disparate scientific theories—from the Big Bang and evolution to string theory and quantum consciousness 4—highlight a recurring tendency that might be termed “parallelomania.” The allure of finding ancient wisdom validated by modern science, or finding deeper meaning in scientific discoveries through mystical frameworks, is understandable. Humans naturally seek patterns and unifying narratives. However, such comparisons often strip concepts from their original context, ignore fundamental differences in methodology and intent, and rely on superficial similarities or numerical coincidences.6 This risks distorting both the historical integrity of Kabbalah and the nature of scientific inquiry, falling into the trap of facile “concordism”.5 A more rigorous scholarly approach involves understanding each system within its own historical and conceptual context, examining documented historical interactions critically, and analyzing structural similarities or differences with careful attention to epistemology, rather than seeking simple, often forced, equivalences. The very motivation for seeking such parallels—whether apologetic, philosophical, or spiritual—is itself a phenomenon worthy of analysis within the broader study of science and religion.

7. Scholarly Perspectives and Critiques: Navigating the Debate

The relationship between Jewish thought, Kabbalah, and science is characterized by a wide spectrum of scholarly interpretations and ongoing debate, with little consensus on many key questions.1 Navigating this complex terrain requires careful attention to the specific nature of the claims being made—distinguishing between arguments for indirect cultural influence, claims of direct theological impact on scientific content or method, accounts of historical participation by Jews in science, analyses of Kabbalah’s historical reception, and explorations of conceptual parallels.

Spectrum of Views on Jewish Thought & Science

Scholarly opinions on the broader connection between Jewish thought and science generally fall into several categories:

- Supportive of Indirect Influence: This perspective, often associated with Max Weber’s thesis, argues that core Jewish concepts—such as monotheistic demythologization leading to a view of a lawful universe, the emphasis on the intelligibility of creation, the cultural value placed on questioning and debate, iconoclasm fostering critical thought, the idea of partnership with God encouraging engagement with the world, and traditions promoting learning and innovation (chiddush)—created an intellectual and cultural milieu in the West that was uniquely conducive to the development of rationality and, subsequently, science.4 Proponents might include figures cited like Jonathan Sacks, Gerald Schroeder, and Judea Pearl, emphasizing different facets of this argument 4, alongside the general Jewish reverence for intellect and education.4

- Critical/Skeptical of Direct Influence: This viewpoint strongly contests the idea that Jewish religious or theological doctrines directly influenced the content or methodology of science. Scholars like Yehuda Bauer and Gad Freudenthal argue that theology and science operate in fundamentally different domains (revelation vs. reason/empiricism).4 They attribute the notable contributions of Jews to science, especially in modernity, primarily to socio-historical factors—such as the high value placed on learning (not necessarily science-specific), historical exclusion from other fields, and the role of science as a path to secularization and assimilation in modern societies that prized scientific achievement.4 Some also point out that “Jewish thought” is too internally diverse and contradictory to exert a single, unified influence.4

- Nuanced/Integrative: This position acknowledges both potential synergies and tensions. It includes historical figures like Maimonides who actively sought to integrate Aristotelian science with Jewish faith, viewing them as compatible paths to divine truth.3 It also encompasses modern perspectives that see science and Judaism as potentially compatible but addressing different questions (e.g., science asking “how,” religion asking “why”) or operating in complementary but distinct domains.3 This approach recognizes the internal diversity within Jewish thought, including the long-standing dialogue and tension between rationalistic and mystical strands.13

Spectrum of Views on Kabbalah & Science

The specific relationship between Kabbalah and science also elicits a range of scholarly views:

- Historical Influence (Renaissance/Early Modern): There is general agreement that Kabbalistic ideas gained currency among Christian intellectuals during the Renaissance and early modern period, attracting the interest of figures like Pico della Mirandola, Reuchlin, Agrippa, and later, Newton and Leibniz.31 The debate centers on the significance and nature of this interest. Was it a direct influence on nascent scientific ideas, or was Kabbalah merely one component within a broader mix of esoteric interests (Hermeticism, alchemy, Neoplatonism) characteristic of the era?43 Scholars emphasize that Christian Cabala involved significant reinterpretation and was often filtered through specific theological or philosophical agendas.38 Gershom Scholem, the foundational scholar of modern Kabbalah studies, situated Kabbalah primarily as a medieval Jewish mystical phenomenon reacting against Maimonidean rationalism, though itself influenced by Gnosticism and Neoplatonism.27

- Conceptual Parallels: Attempts to draw direct conceptual parallels between Kabbalistic doctrines (e.g., Sefirot, Tzimtzum, Shevirah) and modern scientific theories (e.g., string theory, Big Bang, quantum mechanics) are met with varying degrees of enthusiasm and skepticism.4 Some popularizers and thinkers find these parallels deeply meaningful 32, while many academic scholars caution against facile comparisons, highlighting the vast differences in context, methodology, and conceptual meaning.6 Some analyses focus on deeper structural similarities, such as the shared notion of hidden unity underlying surface diversity found in both Kabbalah and structuralist thought 59, or the argument by J. H. Chajes that Kabbalists, like scientists, used diagrams (such as ilanot or Trees of Life) as epistemic tools to map and systematize their knowledge of the cosmos.6

- Kabbalah’s Epistemic Status: There is debate regarding how to characterize Kabbalah’s approach to knowledge. Is it fundamentally “mystical” and thus opposed to or incommensurable with “rational” science?19 Or, as scholars like Gulkowitsch and Chajes suggest, does Kabbalah possess its own internal logic, systematicity, and methods for knowledge production that, while different from empirical science, represent a structured attempt to understand reality?6 This latter view allows for more nuanced comparison, seeing Kabbalah not just as irrational mysticism but as an alternative, albeit esoteric, system of knowledge.

Methodological Challenges

Scholarly work in this area faces several methodological hurdles:

- Anachronism: Avoiding the projection of modern definitions and assumptions about “science,” “religion,” and “mysticism” onto past periods where these categories were understood differently or were more fluid.11

- Defining Terms: Ensuring clarity and consistency in the use of key terms like “Jewish thought,” “Kabbalah,” “rationality,” “science,” and especially “influence,” which can range from vague cultural predisposition to direct causal linkage.2

- Causation vs. Correlation: Distinguishing between genuine historical influence and mere coincidence, parallel development stemming from common sources (e.g., Neoplatonism), or superficial resemblance.

- Mediation and Transformation: Accounting for the role of intermediaries (translators, converts, interpreters) and the significant transformations ideas undergo when crossing cultural, linguistic, and religious boundaries (e.g., Jewish Kabbalah vs. Christian Cabala).38

- Internal Diversity: Recognizing the heterogeneity within both Jewish thought and Kabbalah itself across different periods and schools.2

- Esoteric and Unpublished Sources: The difficulty of assessing the influence of ideas that were deliberately kept secret, circulated only within limited circles, or remained in unpublished manuscripts (e.g., much of Newton’s theological work, many of Leibniz’s writings).45

Summary of Scholarly Positions

To provide a clearer overview of the complex landscape of debate, the following table summarizes key positions on some of the central claims discussed:

| Claim Type | Representative Scholars/Sources (Pro) | Representative Scholars/Sources (Con/Skeptical) | Key Arguments/Nuances |

| Indirect Influence on Rationality/Science | Weber, Sacks, Schroeder, Pearl 4; General value on learning 11 | Bauer, Freudenthal 4; Emphasis on socio-historical factors 4; Logic not unique to Jews 4 | Pro: Demythologization, intelligibility, questioning, iconoclasm, partnership, innovation (chiddush) fostered conducive mindset. Con: Influence overstated, factors not unique, diversity of Jewish thought. |

| Direct Influence on Science Method/Content | Maimonides (motivation) 3; Some see compatibility 7; Potential subtle influence (e.g., predestination/evolution) 22 | Bauer, Freudenthal 4; Different domains (theology vs. science) 7; Modern science driven by internal logic 4 | Pro: Compatibility, theological motivation for inquiry. Con: Fundamentally different epistemologies, lack of evidence for direct impact on scientific practice or theory formation. |

| Kabbalah Influence on Newton | Popular accounts 44; Newton’s interest documented 45 | Scholarly consensus 45; Copenhaver 42 | Pro: Newton studied Kabbalah, sought ancient wisdom. Con: Interest was idiosyncratic, part of anti-Trinitarian project, not a “Christian Kabbalist,” theological work kept secret. |

| Kabbalah Influence on Leibniz | Coudert 53 | Traditional view 53; Attributed to shared Platonism 51 | Pro: Close contact with Christian Kabbalists (Van Helmont, Knorr), illuminates Leibniz’s concepts (monads, harmony). Con: Parallels better explained by shared Platonic roots or general eclecticism. |

| Conceptual Parallel: Kabbalah & Big Bang | Schroeder 4; Tishby/Carmell 32 | Scientific/philosophical critiques 6 | Pro: Beginning from unity/nothingness, role of light/energy. Con: Superficial, ignores vast differences in framework (divine purpose vs. naturalism), epistemology, and context. |

| Conceptual Parallel: Sefirot & String Theory | Tishby/Carmell 32 | Academic critiques 59 | Pro: Numerical coincidence (10 Sefirot / 10 dimensions), mapping 3+7 structure. Con: Highly speculative, post hoc, ignores conceptual differences (theological attributes vs. mathematical dimensions). |

This table illustrates the contested nature of many claims and the importance of considering the specific arguments and evidence presented by different scholars.

8. Conclusion: Synthesizing a Multifaceted Relationship

The exploration of the relationship between Jewish thought, Kabbalah, and the development of science reveals a complex tapestry woven with threads of synergy, tension, historical contingency, and profound intellectual engagement. No single, simple narrative—whether of inherent conflict or predetermined harmony—adequately captures the multifaceted interactions across centuries.5

The analysis suggests that while claims of direct theological influence of Jewish religious doctrines on the specific content or methodology of science remain highly contested and often lack robust evidence, a plausible case can be made for indirect contributions. Certain cultural and intellectual tenets embedded within historical Jewish thought—such as the demythologization of nature leading to a view of a lawful universe, the emphasis on the intelligibility of God’s creation, the high value placed on questioning and rigorous debate, an iconoclastic tendency to challenge norms, and perhaps even the theological mandate for partnership with God in perfecting the world—likely fostered aspects of a worldview conducive to the rise of Western rationality and scientific inquiry. However, these influences must be understood within the context of broader historical developments and alongside socio-historical factors that shaped Jewish engagement with science, particularly in the modern era. Furthermore, the “rationality” involved was often a specific, dialectical form deeply intertwined with textual tradition.

Historically, the participation of Jewish individuals in scientific activity is undeniable, most notably their crucial role as translators and transmitters of classical and Islamic science to medieval Europe. This intermediary function was vital for the preservation and dissemination of knowledge. From the Middle Ages onward, Jewish thinkers like Maimonides actively sought to integrate scientific understanding with religious faith, navigating the persistent tension between reason and revelation.

The role of Kabbalah adds another layer of complexity. While often positioned in opposition to rationalism, Kabbalah represents a sophisticated, internally structured system of esoteric thought with its own complex cosmology and epistemology. Its historical encounter with early modern European thought, primarily through the filter of Christian Cabala, shows how mystical ideas entered the broader intellectual currents of the time, attracting the interest of figures like Pico, Newton, and Leibniz. However, the influence was largely mediated, selective, and transformative, making direct causal links to specific scientific breakthroughs difficult to establish definitively. Conceptual parallels drawn between Kabbalistic frameworks and modern scientific theories, while sometimes intriguing, often suffer from lack of methodological rigor and risk distorting both traditions through anachronistic comparison.

Ultimately, understanding the relationship requires appreciating its dynamic and multifaceted nature. It involves navigating internal Jewish debates between rationalism and mysticism, acknowledging the impact of external historical forces like persecution and emancipation, recognizing the crucial role of cultural exchange and intellectual transmission (often involving reinterpretation), and carefully distinguishing between different types of influence—from broad cultural predispositions to specific conceptual borrowings. The dialogue between Jewish thought, in its various forms, and scientific inquiry continues to evolve.1 Studying these historical and conceptual intersections remains valuable, not only for illuminating the complex history of science and religion but also for enriching our understanding of the development and adaptability of Jewish intellectual and spiritual traditions themselves. The entangled paths of faith, mysticism, and reason continue to invite exploration.

Works cited

- Religion and Science – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/religion-science/

- Philosophy and Jewish Thought – Theoretical Intersections – transcript Verlag, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.transcript-verlag.de/media/pdf/c5/cc/bd/oa9783839472927.pdf

- Judaism & Science in History | My Jewish Learning, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/judaism-science-in-history/

- How Has Jewish Thought Influenced Science? – Moment Magazine, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://momentmag.com/jewish-thought-influenced-science/

- Disentangling the Histories of Science and Religion – The ISCAST Journal, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://journal.iscast.org/past-issues/disentangling-the-histories-of-science-and-religion

- Roots in Heaven, Branches on Earth – Jewish Review of Books, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/jewish-history/13879/roots-in-heaven-branches-on-earth/

- The Theory of Evolution – A Jewish Perspective – PMC, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3721658/

- Exploring Jewish Philosophy: Ancient Wisdom Today – Scripture Analysis, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.scriptureanalysis.com/exploring-jewish-philosophy-ancient-wisdom-today/

- Into the Unknown: The Spirit of Adventure in Science and Judaism – GalEinai, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://inner.org/into-the-unknown-the-spirit-of-adventure-in-science-and-judaism/

- Key Concepts in Kabbalah | Intro to Judaism Class Notes – Fiveable, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/introduction-to-judaism/unit-13/key-concepts-kabbalah/study-guide/4F4T5xMbDwVrLt8j

- Ancient Jewish Sciences and the History of Knowledge in Second Temple Literature, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://dlib.nyu.edu/awdl/isaw/ancient-jewish-sciences/chapter2.xhtml

- Jewish Thought and Scientific Discovery in Early Modern Europe – DL 1, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://dl1.cuni.cz/pluginfile.php/890005/mod_resource/content/3/Ruderman_Jewish_Thought_and_Scientific_Discovery_in_Early_Modern_Europe.pdf

- RELATIONS BETWEEN THE RATIONAL AND THE MYSTICAL IN SOME WORKS OF LAZAR GULKOWITSCH, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.kirj.ee/public/trames/trames-2006-2-2.pdf

- 20th WCP: Jewish Philosophers on Reason and Revelation, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.bu.edu/wcp/Papers/Reli/ReliShea.htm

- T. M. Rudavsky. Jewish Philosophy in the Middle Ages: Science, Rationalism, and Religion. The Oxford History of Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. 305 pp. | AJS Review | Cambridge Core, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ajs-review/article/t-m-rudavsky-jewish-philosophy-in-the-middle-ages-science-rationalism-and-religion-the-oxford-history-of-philosophy-oxford-oxford-university-press-2018-305-pp/3C9431A95A75AE64CBA5F7C3317E6936

- Jewish Philosophy in the Middle Ages: Science, Rationalism, and …, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://ndpr.nd.edu/reviews/jewish-philosophy-in-the-middle-ages-science-rationalism-and-religion/

- Jewish Science in the Middle Ages | My Jewish Learning, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/jewish-science-in-the-middle-ages/

- Jewish views on evolution – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_views_on_evolution

- Rationalisim vs. Mysticism: Book Review | jewishideas.org, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.jewishideas.org/article/rationalisim-vs-mysticism-book-review

- Famous Jews and Jewish Contributions to Science, Business and Culture | Middle East And North Africa, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://africame.factsanddetails.com/article/entry-802.html

- The Demarcation of Science and Religion | Discovery Institute, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.discovery.org/a/3524/

- The influence of religion on science: the case of the idea of predestination in biospeleology – RIO Journal, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://riojournal.com/article/9015/

- Creationism vs Evolution, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.goshen.edu/bio/Biol410/bsspapers02/alyssa.htm

- What is Kabbalah? | Reform Judaism, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://reformjudaism.org/beliefs-practices/spirituality/what-kabbalah

- Kabbalah – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabbalah

- Kabbalah and Jewish Mysticism – Judaism 101 (JewFAQ), accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.jewfaq.org/kabbalah_and_mysticism

- Gershom Scholem – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scholem/

- (PDF) Jewish Mysticism and Morality: Kabbalah and its Ontological Dualities, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291205058_Jewish_Mysticism_and_Morality_Kabbalah_and_its_Ontological_Dualities

- Spherical Sefirot in Early Kabbalah | Harvard Theological Review | Cambridge Core, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/harvard-theological-review/article/spherical-sefirot-in-early-kabbalah/020C76B822F155BF0235A5BD61CA780A

- (PDF) Correspondences in Jewish Mysticism/Kabbalah – ResearchGate, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332091804_Correspondences_in_Jewish_MysticismKabbalah

- Celestial Intelligences: Cabala, Angelic Hierarchies, and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola’s Syncretic Philosophy – Harvard, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://thesis.extension.harvard.edu/files/thesis/files/religion.picocelestialintelligences.pdf

- Kabbalah, Science and the Creation of the Universe – Jewish Action, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://jewishaction.com/science-technology/kabbalah-science-creation-universe/

- Three Texts on the Kabbalah. More, Wachter, Leibniz, and the Philosophy of the Hebrews | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316808252_Three_Texts_on_the_Kabbalah_More_Wachter_Leibniz_and_the_Philosophy_of_the_Hebrews

- Spheres, Sefirot, and the Imaginal Astronomical Discourse of Classical Kabbalah | Harvard Theological Review – Cambridge University Press, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/harvard-theological-review/article/spheres-sefirot-and-the-imaginal-astronomical-discourse-of-classical-kabbalah/6406AC47AA34ACAFCA9E9F99823AF630

- Ibn Gabirol Between Philosophy and Kabbalah. A Comprehensive Insight into the Jewish Reception of Ibn Gabirol – Brepols Online, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/10.1484/M.PATMA-EB.5.133987?mobileUi=0

- YOM ṬOV LIPMANN’S STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN: COSMOLOGY AND KABBALAH IN LATE MEDIEVAL JEWISH CUSTOM – Ceu, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.etd.ceu.edu/2015/sivek_liat.pdf

- Samuel Lebens: The Line Between Rationality and Mysticism – 18Forty, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://18forty.org/podcast/samuel-lebens-the-line-between-rationality-and-mysticism/

- The Study of Christian Cabala in English – CiteSeerX, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=be567917b95c4e2e951b766458c599bb3421c150

- The Study of Christian Cabala in English – MagicGateBg, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://magicgatebg.com/Books/The%20Study%20of%20Christian%20Cabala%20in%20English%20by%20Don%20Karr.pdf

- Pico in English: A Bibliography of the Works of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola – M.V. Dougherty, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://www.mvdougherty.com/pico.htm

- Pico in English: A Bibliography of the Works of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola – M.V. Dougherty, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://www.mvdougherty.com/1stEditionPicoinEnglish.htm

- Magic in Western Culture: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment: 9781107070523: Copenhaver, Brian P.: Books – Amazon.com, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Magic-Western-Culture-Antiquity-Enlightenment/dp/110707052X

- The Influence of Renaissance Thought on the Scientific Revolution – ResearchGate, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264443219_The_Influence_of_Renaissance_Thought_on_the_Scientific_Revolution

- Kabbalah’s Influence on the Development of Modern Science, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://livekabbalah.org/kabbalahs-influence-on-the-development-of-modern-science/

- Maimonides, Stonehenge, and Newton’s Obsessions – Jewish Review of Books, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/articles/3215/maimonides-stonehenge-and-newtons-obsessions/

- Sir Isaac Newton as Religious Prophet, Heretic, and Reformer | Church Life Journal, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/sir-isaac-newton-as-religious-prophet-heretic-and-reformer/

- Full text of “Judaism in the Theology of Sir Isaac Newton [electronic resource]”, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://archive.org/stream/springer_10.1007-978-94-017-2014-4/10.1007-978-94-017-2014-4_djvu.txt

- Selected Works about Isaac Newton and his Thought, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.newtonproject.ox.ac.uk/bibliography

- leibniz, gottfried wilhelm, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://isidore.co/misc/Res%20pro%20Deo/Encyclopedia%20of%20Philosophy%20(Alcuin%20Books%20has%201st,%202%20vol.%20ed.%20of%20this)/Leibniz__Gottfried_Wilhelm__16.PDF

- Leibniz: The Last Great Christian Platonist – Brill, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://brill.com/downloadpdf/book/edcoll/9789004285163/BP000010.pdf

- Leibniz’s Cosmology: Transcendental Rationalism and Kabbalistic Symbolism – Open Research Online, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://oro.open.ac.uk/59414/1/288348.pdf

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/leibniz/

- Leibniz And The Kabbalah ; Terry Melanson (2024) 10years.emba.ntnu.edu.tw, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://10years.emba.ntnu.edu.tw/form-library/Resources/fetch.php/leibniz_and_the_kabbalah.pdf

- Leibniz and the Kabbalah – AP Coudert – PhilPapers, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://philpapers.org/rec/COULAT

- THE VITALISM OF FRANCIS MERCURY VAN HELMONT: ITS INFLUENCE ON LEIBNIZ – Rausser College of Natural Resources, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://nature.berkeley.edu/departments/espm/env-hist/articles/11.pdf

- Leibniz: Philosophy of Religion – Bibliography – PhilPapers, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://philpapers.org/browse/leibniz-philosophy-of-religion

- Leibniz on the Trinity and the Incarnation: Reason and Revelation in the Seventeenth Century | Yale Scholarship Online | Oxford Academic, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/yale-scholarship-online/book/19638

- FROM SACRED HISTORY TO THE HISTORY OF RELIGION: PAGANISM, JUDAISM, AND CHRISTIANITY IN EUROPEAN HISTORIOGRAPHY FROM REFORMATION TO ‘ENLIGHTENMENT’* | The Historical Journal – Cambridge University Press, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/historical-journal/article/from-sacred-history-to-the-history-of-religion-paganism-judaism-and-christianity-in-european-historiography-from-reformation-to-enlightenment/918D0F96F350E2B2106477CD35829D3E

- (PDF) Structuralism and Kabbalah: Sciences of Mysticism or Mystifications of Science?, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236826988_Structuralism_and_Kabbalah_Sciences_of_Mysticism_or_Mystifications_of_Science

- Kabbalah and the Enigma of Consciousness – Part 3 of a 3-part series – Chabad.org, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/5615890/jewish/Kabbalah-and-the-Enigma-of-Consciousness.htm

- Full article: An Historical Overview of Jewish Theological Responses to Evolution, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14746700.2023.2255948

- Introduction to Jewish Mysticism and Esotericism | Center for Online Judaic Studies, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://cojs.org/introduction_to_jewish_mysticism_and_esotericism/

- (PDF) Philosophical Approaches of Religious Jewish Science Teachers Toward the Teaching of ‘Controversial’ Topics in Science – ResearchGate, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248974503_Philosophical_Approaches_of_Religious_Jewish_Science_Teachers_Toward_the_Teaching_of_’Controversial’_Topics_in_Science

Data Google Gemini 2.5 Deep Research / Audio Google LM Plus / Pictures Microsoft Director Curated by FoundationP