I. Introduction: The Enduring Shadow of Original Sin

The doctrine of Original Sin stands as a cornerstone of Western Christian theology, yet it remains one of its most debated and psychologically potent concepts.1 It posits a fundamental flaw in human nature, an inherited condition stemming from the primordial disobedience of Adam and Eve, which shapes theological understandings of humanity, sin, grace, and salvation.4 This doctrine, however, finds no direct parallel in Judaism, which offers a contrasting view of human nature, free will, and the path to reconciliation with the divine.8 The stark divergence between these traditions highlights the particularity of the Original Sin framework and its profound consequences.

The significance of Original Sin extends far beyond theological discourse. It has cast a long shadow over Western culture, deeply influencing conceptions of guilt, shame, ethics, sexuality, and the body.9 Its emphasis on innate corruption has been linked to pervasive feelings of guilt, anxiety, and diminished self-worth, contributing to what some anthropologists and historians term a “guilt culture”.12 The doctrine’s historical association with sexual desire as the mechanism of its transmission has also fostered a complex and often troubled relationship with sexuality within Christian traditions.13

This report undertakes a scholarly, in-depth examination of Original Sin, navigating its complex terrain through multiple disciplinary lenses. It will analyze the theological origins and development of the doctrine, scrutinizing its scriptural basis and the pivotal role of Augustine of Hippo.3 It will trace its historical evolution and variations across major Christian denominations, contrasting these with the distinct Jewish understanding of sin and human inclination (Yetzer Hara/Tov).8 Furthermore, this inquiry will incorporate psychoanalytic perspectives, drawing on Freudian, Kleinian, and Lacanian theories to interpret the concepts of guilt, the superego, religious belief, and acts of expiation such as corporal mortification.21 Ultimately, this multi-layered approach aims to assess the societal and psychological burdens imposed by religious frameworks centered around innate guilt and inherited sinfulness.6

A central tension animates this exploration: the doctrine’s paradoxical status within Christianity itself. Proponents view Original Sin as indispensable for understanding the human predicament and the absolute necessity of Christ’s redemptive work.3 Without it, the logic of salvation, particularly the need for divine grace and atonement, appears diminished. Yet, critics, both within and outside the Christian tradition, challenge its foundations and consequences. They question its scriptural exegesis, pointing to ambiguities in key texts like Genesis 3 and Romans 5:12.1 They highlight its historical contingency, particularly its formulation by Augustine in the context of specific theological debates and philosophical influences.6 Ethically, it raises profound questions about justice, free will, and responsibility, particularly the notion of inheriting guilt for an ancestor’s actions.6 Psychologically, it is often seen as fostering excessive guilt, anxiety, repression, and a negative view of the self.30 This inherent conflict between the doctrine’s perceived theological necessity and its problematic nature necessitates a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach.

Understanding such a multifaceted concept requires moving beyond the confines of pure theology. History reveals the doctrine’s evolution and its tangible impact on societies.1 Comparative religion, particularly the contrast with Judaism’s alternative framework, sharpens our understanding of its unique features and assumptions.8 Psychology and psychoanalysis offer crucial tools for analyzing the doctrine’s core themes of guilt, desire, the will, and its effects on the individual psyche.17 Finally, sociology and cultural studies illuminate its role in shaping Western norms, ethics, and cultural anxieties.6 Only by integrating these diverse perspectives can the full weight and complexity of Original Sin’s legacy be adequately assessed.

II. The Genesis and Augustinian Architecture of Original Sin

The doctrine of Original Sin, as understood in the Western Christian tradition, is not a direct transcription of biblical text but rather a theological construct developed over centuries, built upon specific interpretations of key scriptural passages and significantly shaped by the thought of Augustine of Hippo. Understanding its origins requires examining both the biblical narratives cited in its support and the historical and theological context in which the doctrine took shape.

A. Scriptural Roots and Pre-Augustinian Interpretations

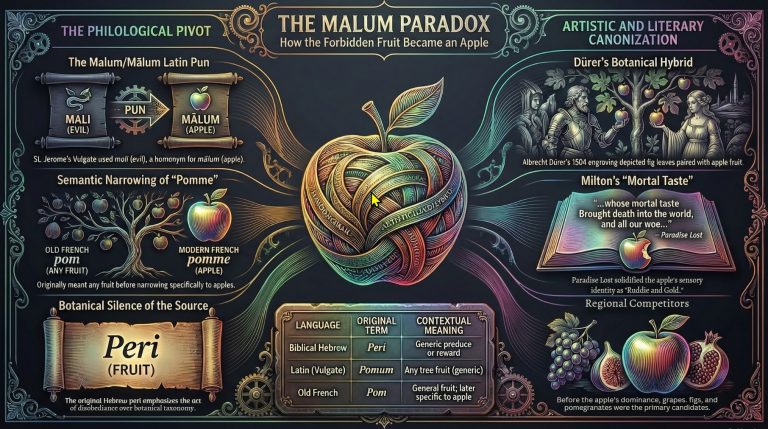

The foundational texts most frequently invoked to support the doctrine of Original Sin are Genesis 3, Romans 5:12, and Psalm 51:5. However, a critical examination reveals considerable interpretive distance between these texts in their original contexts and the later, fully formed Augustinian doctrine.

Genesis 3: This chapter narrates the story of the first human couple, Adam and Eve, their disobedience in eating the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, and their subsequent expulsion from the Garden of Eden.1 Traditionally interpreted as “the Fall” – a catastrophic event plunging humanity into sin and corruption 1 – the text itself is notably silent on concepts like inherited guilt or innate sinfulness.1 The explicit consequences mentioned are toil in labor, pain in childbirth, enmity with the serpent, and eventual physical death (“dust you are and to dust you shall return”).6 Historical-critical scholarship often suggests alternative interpretations: the story might primarily serve an etiological function, explaining the origins of human hardship, or it might narrate God’s action to prevent humans from achieving divine immortality by eating from the Tree of Life after gaining knowledge.6 Early Jewish interpretations during the Second Temple period (c. 500 BCE–70 CE), while discussing Adam’s transgression, generally did not include the notion that his sin or guilt was biologically inherited by his descendants.1

Romans 5:12: The Apostle Paul’s statement, “Therefore, just as sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned…” is arguably the most crucial text for the doctrine’s development.1 However, Paul’s understanding of “Sin” (often capitalized by scholars to denote his specific usage) appears to be that of a personified cosmic power or force that enslaves humanity, rather than simply individual transgressions or an inherited state of guilt.6 Adam’s disobedience is seen as empowering this cosmic force, leading to the reign of Death over all humanity.2 The final clause, eph hō pantes hēmarton (“because all sinned”), is notoriously ambiguous and heavily debated. While Augustine, influenced by a Latin translation, would interpret it as “in whom [Adam] all sinned,” this is not the necessary or universally accepted meaning of the Greek.2 Paul’s focus seems to be on the universal reign of Death initiated by Adam’s act, which implicates all humanity under the power of Sin, leading to their own individual sinning. Early Christian writers like Clement of Rome and Ignatius of Antioch acknowledged universal sinfulness but did not explicitly articulate an Augustinian-style doctrine of hereditary transmission from Adam.1 Irenaeus, in the 2nd century, utilized the concept of Adam’s fall and its consequences in his arguments against Gnosticism, laying some groundwork, but without the specific emphasis on inherited guilt.1

Other Texts: Psalm 51:5, “Behold, I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin did my mother conceive me,” is often cited as evidence for innate sinfulness from conception.1 However, this verse occurs within a personal psalm of repentance (traditionally attributed to David after his affair with Bathsheba) and may be interpreted as a hyperbolic expression of personal unworthiness and the pervasiveness of sin in human life, rather than a formal theological statement about the ontological state of all humans at birth.1

These foundational scriptural passages, therefore, exhibit significant ambiguity regarding the core tenets of the later doctrine of Original Sin, particularly the concept of inherited guilt. Genesis 3 does not explicitly mention inherited sin or guilt, focusing instead on other consequences. Romans 5:12, while linking Adam’s act to universal sin and death, uses the concept of “Sin” as a cosmic power and contains a highly contested causal clause (eph hō). Psalm 51:5 is open to interpretation as personal lament rather than universal doctrine. Pre-Augustinian Christian thought wrestled with universal sinfulness but lacked the specific formulation of inherited guilt transmitted biologically that Augustine would later develop.1 This suggests that the doctrine, in its classical Western form, represents a theological construction built upon these scriptures through specific interpretive choices, rather than being a direct and unambiguous teaching from them.6

B. Augustine’s Synthesis: Inherited Guilt and Concupiscence

It was Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE), a North African theologian of immense influence, who synthesized earlier ideas and scriptural interpretations into the coherent doctrine of Original Sin that would dominate Western Christian thought.1 He was the first known author to use the specific phrase peccatum originale.1 Augustine’s formulation was driven not only by his reading of scripture but also significantly shaped by his philosophical background and, crucially, by the theological controversies of his day, most notably his debate with Pelagius.1

Central to Augustine’s argument was his interpretation of Romans 5:12. Relying on a faulty Latin translation by Ambrosiaster which rendered eph hō as in quo (“in whom”), Augustine argued that all humanity was seminally present in Adam and thus participated in his sin.6 This interpretation established the concept of inherited guilt (reatum): Adam’s transgression was not merely his own but a collective act for which all subsequent generations bear culpability from birth.6 Humanity, consequently, became a massa damnata, a “mass of perdition,” inherently deserving of condemnation.1

Augustine needed a mechanism to explain how this sinful state and guilt were transmitted across generations. He identified this mechanism as concupiscence – disordered desire, particularly the involuntary passion associated with sexual intercourse.3 He argued that Adam’s sin resulted not only in guilt but also in a corruption of human nature, a weakening of the will, and the emergence of this unruly desire.6 Because procreation occurs through the sexual act, marked by concupiscence, the sin itself is transmitted biologically, like a hereditary disease or “contagion,” from parents to child.3 This view was likely influenced by Augustine’s own well-documented personal struggles with sexuality before his conversion and potentially by the dualistic tendencies of Manichaeism and Neoplatonism, which often viewed the body and its passions negatively.10 Augustine distinguished between the peccatum originale originans (the originating sin of Adam) and the peccatum originale originatum (the originated, inherited sinful state characterized by concupiscence).28

This inherited corruption had profound implications for human free will and the necessity of grace. Augustine argued that after the Fall, human free will was so damaged that, while humans could still choose, they were fundamentally unable to choose the good or avoid sin without the intervention of God’s grace.3 This grace, for Augustine, had to be prevenient – coming before and enabling any human good action, including faith itself.42 This led Augustine to emphasize divine predestination: God sovereignly chooses whom to save, bestowing the necessary grace.42

Augustine’s doctrine was sharpened and solidified in his fierce opposition to Pelagius, a British monk who taught that humans are born morally neutral, possessing the inherent free will to choose good or evil.3 Pelagius believed Adam’s sin affected humanity primarily through bad example, and that divine grace was helpful but not absolutely essential for living a righteous life.3 Augustine saw this as a grave threat, undermining the necessity of Christ’s redemption and the centrality of divine grace.3 Against Pelagius, Augustine forcefully argued for inherited guilt, the bondage of the will to sin, and the absolute necessity of grace, mediated through the Church, particularly through infant baptism, which he deemed essential for washing away the stain of original sin and rescuing infants from the damnation they otherwise inherited.1

The development of Augustine’s doctrine, therefore, appears significantly driven by his polemical needs. Faced with Pelagius’s emphasis on human autonomy, Augustine constructed a theological framework emphasizing radical human dependence on divine grace. This required positing an inherent corruption and inherited guilt transmitted from Adam, interpretations arguably pushed beyond the explicit statements of scripture to counter the Pelagian threat and uphold the necessity of the Church’s sacramental system, especially infant baptism.3 His doctrine provided a powerful explanation for the universality of sin and the need for redemption through Christ, but it did so by employing specific and debatable scriptural readings and philosophical assumptions.

Furthermore, Augustine’s specific choice of concupiscence – sexual desire and the act of procreation – as the mechanism for transmitting Original Sin had lasting and problematic consequences. It deeply ingrained a suspicion of sexuality within Western Christianity, linking the very act of bringing new life into the world with the propagation of sin and corruption.3 This stands in contrast to the Genesis narrative itself, which does not connect the first sin with sexuality 1, and Paul’s affirmation of marriage.29 This Augustinian linkage contributed significantly to historical Christian ambivalence or negativity towards the body, pleasure, and sexual expression, influencing ethical norms and theological discourse for centuries.10

C. Doctrinal Solidification and Variations

Augustine’s formulation of Original Sin, particularly its emphasis on inherited guilt and the necessity of baptism, quickly gained traction in the Western Church. The Councils of Carthage (418 CE) and Orange (529 CE) largely affirmed his anti-Pelagian stance, condemning Pelagius’s views and incorporating key aspects of Augustine’s doctrine into official Church teaching, thus solidifying its place in Western theology.1 Later theologians, like Anselm of Canterbury in the 11th century, extended the logic, arguing that unbaptized infants, dying in a state of original sin, were damned, albeit perhaps to a lesser state than adults who committed actual sin.29 However, interpretations and emphases continued to evolve, leading to significant variations across different Christian traditions.

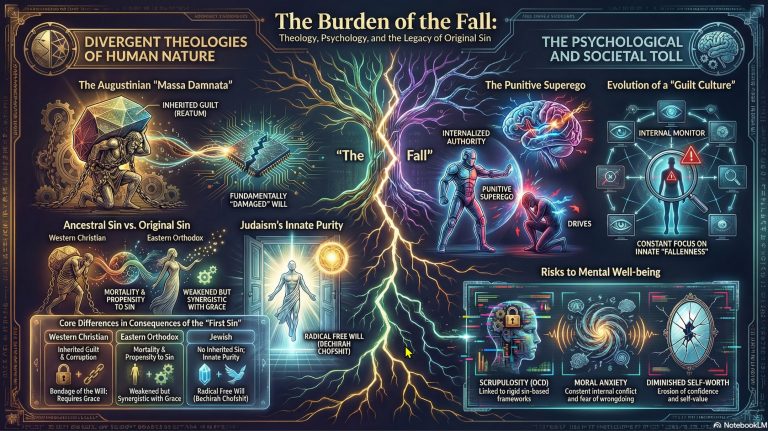

Catholic Interpretation: Contemporary Catholic theology distinguishes between original sin as a state and personal guilt (culpa).1 Original sin is understood as the inherited deprivation of the original holiness and justice enjoyed by Adam and Eve before the Fall.1 It is a state “contracted,” not “committed” by individuals.1 While this state results in a weakened human nature inclined towards sin (concupiscence remains even after baptism), the Catholic Church explicitly denies that the personal guilt of Adam is inherited.1 Baptism is seen as erasing the state of original sin by infusing sanctifying grace, restoring the relationship with God, although the tendency towards sin (concupiscence) persists.1 The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, formally defined in 1854, posits that Mary, the mother of Jesus, was preserved from the stain of original sin from the moment of her own conception.19 This doctrine is seen as necessary within the Augustinian framework: if sin is transmitted generationally, Mary needed to be free from this inherited state to bear the sinless Christ.18

Eastern Orthodox Interpretation (Ancestral Sin): The Eastern Orthodox Church fundamentally diverges from the Augustinian and subsequent Western traditions by rejecting the concept of inherited guilt.1 The Orthodox speak of “Ancestral Sin” (προπατορικὴ ἁμαρτία, propatorikē hamartia).39 They affirm that humanity inherits the consequences of Adam and Eve’s transgression – primarily mortality, corruption, and a propensity towards sin due to existing in a fallen world – but not their personal guilt.39 The Greek term amartia (sin as “missing the mark”) describes the universal human condition, while amartema refers to Adam’s specific, individual act.39 Death, not guilt, is seen as the primary inheritance passed down.39 Consequently, salvation (theosis, or deification) is understood less in juridical terms (forgiveness of guilt) and more as a therapeutic process of healing human nature from corruption and death through participation in the divine life offered in Christ.39 The image of God in humanity is seen as tarnished or damaged by the Fall, but not destroyed.39 This perspective avoids the Western focus on inherited guilt and divine wrath, emphasizing instead divine compassion and the restoration of human nature.39

Protestant Interpretations (Total Depravity): The Protestant Reformation largely embraced the Augustinian framework of Original Sin, often intensifying its implications under the doctrine of Total Depravity.7 This doctrine, shared in essence by major Protestant traditions (Calvinism, Lutheranism, Arminianism/Methodism), asserts that as a consequence of the Fall, human nature is thoroughly corrupted by sin, rendering individuals utterly unable to achieve salvation through their own efforts or merits.20 However, significant disagreements exist regarding the precise nature and consequences of this depravity:

- Calvinism (Reformed): Strongly emphasizes God’s sovereignty. Total depravity means total inability to choose good or respond to God apart from divine intervention. This leads to the doctrines summarized by the acronym TULIP: Total Depravity, Unconditional Election (God chooses who will be saved based solely on His will, not foreseen faith), Limited Atonement (Christ died only for the elect), Irresistible Grace (God’s saving grace cannot be resisted by the elect), and Perseverance of the Saints (the elect will inevitably persevere in faith).20 Inherited guilt (culpa) is typically affirmed.43

- Lutheranism: Agrees with Calvinism on total depravity and salvation by grace through faith alone.48 However, Lutherans generally reject double predestination (the idea that God actively predestines some to damnation) and often hold to a view of unlimited atonement (Christ died for all, though only believers benefit).48 Grace is seen as resistible. The Formula of Concord strongly affirms total depravity.48 There’s a hybridity noted by some scholars, mixing Calvinist and Arminian elements on depravity’s implications.54

- Arminianism/Methodism: While affirming total depravity (humanity cannot save itself), Arminianism posits the necessity of prevenient grace – a universal grace from God that enables fallen humans to freely respond to the offer of salvation.20 This leads to conditional election (God elects based on foreseen faith), unlimited atonement, resistible grace, and the possibility of falling from grace (conditional perseverance).48 There is often a distinction made between the inherited sinful condition (original sin) and inherited personal guilt, with the latter often denied or downplayed, especially concerning infants who are seen as covered by Christ’s atonement.51 John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, considered Original Sin foundational but his strong emphasis on its judicial and punitive aspects created theological tensions with his doctrines of free will (enabled by prevenient grace) and Christian perfection (entire sanctification).7

The core divergence between the Eastern and Western traditions clearly lies in the understanding of what is inherited: is it primarily Adam’s guilt, leading to a state of condemnation requiring juridical satisfaction, or is it primarily mortality and corruption, a disease requiring therapeutic healing and restoration?.1 Augustine’s interpretation of Romans 5:12, emphasizing shared guilt, set the trajectory for the West (Catholicism and Protestantism), leading towards soteriological models focused on atonement for guilt, such as satisfaction theory and penal substitution.39 The East, maintaining a focus on inherited death, developed models centered on Christ’s victory over death and the devil, and the process of deification (theosis).39 These differing starting points profoundly affect views on baptism, the role of Mary, and the understanding of human capacity and salvation.

Within Protestantism, while united by the concept of Total Depravity stemming from the Augustinian tradition, deep fissures remain concerning its implications.20 The debates between Calvinism and Arminianism, for instance, over unconditional versus conditional election, or irresistible versus prevenient grace, echo the fundamental questions about divine sovereignty and human response that were already present in the Augustine-Pelagius controversy.20 These internal Protestant tensions demonstrate the enduring difficulty of reconciling the concept of inherited human corruption with notions of divine justice and human agency within the framework established by the doctrine of Original Sin.

The following table summarizes the key variations:

Table 1: Comparative Views on the Consequences of the First Sin

| Feature | Catholicism | Eastern Orthodoxy (Ancestral Sin) | Calvinism | Lutheranism | Arminianism/Methodism |

| Inherited Element | State of deprivation (loss of original holiness/justice); Concupiscence 1 | Mortality, Corruption (disease-like state); Propensity to sin 39 | Corrupt Nature (Total Depravity); Often Inherited Guilt (culpa) 20 | Corrupt Nature (Total Depravity) 48 | Corrupt Nature (Total Depravity); Concupiscence; Guilt often distinguished/denied 20 |

| Impact on Free Will | Weakened, inclined to evil (concupiscence), requires grace 1 | Weakened by corruption/mortality, requires synergy with grace 46 | Unable to choose good without irresistible grace (Total Inability) 20 | Unable to contribute to salvation without grace 48 | Unable to choose good without prevenient grace, but enabled to respond by it 20 |

| Nature of Sin (Inherited) | A state “contracted,” not “committed” 1 | A condition/disease transmitted; not personal guilt 39 | An inherent state of corruption and guilt 20 | An inherent state of corruption 48 | An inherent state of corruption; universality of actual sin follows 5 |

| Primary Consequence | Death, Loss of Grace, Concupiscence 1 | Death, Corruption 39 | Death, Guilt, Condemnation 5 | Death, Condemnation 48 | Death, Separation from God, Inclination to sin 5 |

| Role of Baptism | Removes state of original sin, imparts grace 1 | Initiation into new life, start of healing/deification 39 | Sign/seal of covenant, necessary for infants due to guilt (often) 41 | Means of grace, regeneration 48 | Means of grace, addresses original sin (view varies on guilt) 7 |

| Primary Soteriological Metaphor | Primarily Juridical (satisfaction, merit) but also Therapeutic 1 | Primarily Therapeutic/Ontological (healing, deification) 39 | Primarily Juridical (penal substitution, imputation) 47 | Primarily Juridical (justification by faith) 47 | Mix of Juridical (atonement) and Therapeutic (sanctification) 7 |

III. A Counter-Narrative: Judaism on Sin, Inclination, and Responsibility

In stark contrast to the Christian doctrine of Original Sin, particularly its Augustinian formulation, Judaism offers a fundamentally different understanding of human nature, sin, and the relationship between humanity and God. This perspective emphasizes human agency, the potential for good, and the ever-present possibility of return (Teshuvah).

A. Human Nature and Creation

The foundational difference lies in the rejection of the concept of Original Sin itself. Judaism teaches that human beings enter the world pure and sinless, created in the image of God.8 There is no inherited guilt or innate corruption passed down from Adam and Eve’s transgression.8 While the story of Adam and Eve’s disobedience in the Garden of Eden is part of Jewish scripture, its interpretation differs significantly from the Christian concept of “the Fall.” Rather than viewing it as a catastrophic event that fundamentally corrupted human nature and transmitted guilt, Jewish thought often sees it as the event that introduced mortality and the internalization of the struggle between good and evil into the human experience, but not an inherent stain of sinfulness.36

Central to the Jewish understanding of human nature is the belief in free will (bechirah chofshit). God endowed humans with the capacity to choose between good and evil, making them morally responsible agents.8 This capacity for choice is not fundamentally compromised by an inherited sinful nature; rather, it is the defining characteristic that allows for meaningful moral action and relationship with God. Goodness is not impossible, merely challenging at times.8

B. The Dynamics of Inclination: Yetzer Hara and Yetzer Tov

Instead of a single, corrupted nature, Jewish tradition posits that humans possess two innate inclinations: the Yetzer Hatov (the good inclination) and the Yetzer Hara (often translated as the evil inclination).8 The Yetzer Hatov represents the drive towards morality, altruism, spiritual connection, and fulfilling God’s commandments.34 The Yetzer Hara, conversely, is the inclination towards self-interest, physical desires, ego, and immediate gratification.8

Crucially, the Yetzer Hara is not seen as intrinsically evil or demonic, despite its common translation.55 Rabbinic thought views it as a necessary component of human existence, the engine driving essential life activities such as procreation, ambition, building, and commerce.8 One rabbinic midrash even tells of the sages capturing the Yetzer Hara, only to find that the world ground to a halt without it, forcing them to release it.59 The Yetzer Hara becomes problematic only when it dominates the individual, leading them to transgress divine commandments, or when its inherent drives (like hunger or sexual desire) are indulged excessively or improperly (leading to gluttony or promiscuity).34 It represents the raw, amoral, “animalistic” aspect of human nature that needs to be channeled and guided, not eradicated.57

The human condition, therefore, is characterized by an ongoing internal struggle between these two inclinations.34 Unlike the Augustinian view where the will is inherently biased towards evil without grace, Judaism posits that humans have the God-given capacity, through free will and guided by the Torah and mitzvot (commandments), to master the Yetzer Hara and choose the path of the Yetzer Hatov.34 The challenge lies in this continuous effort of self-mastery and ethical choice. Some traditions suggest the Yetzer Hara is present from birth, while the Yetzer Tov develops later, often associated with moral maturity (around Bar/Bat Mitzvah age), initially placing the good inclination at a disadvantage.34

C. Sin as Action and the Path of Teshuvah

Consistent with its emphasis on free will and individual responsibility, Judaism defines sin primarily as an action – a violation of one of the 613 commandments (mitzvot) that structure the covenantal relationship between God and the Jewish people.8 Hebrew terms for sin, such as ḥeṭ (missing the mark, often unintentional), avon (iniquity, moral failing), and pesha (rebellion, intentional transgression), all point towards specific acts or failures to act, rather than an inherited state of being.8 While acknowledging the human tendency towards wrongdoing (“from youth,” Gen 8:21) 8, Judaism maintains that individuals are accountable only for their own actions, not for the primordial sin of Adam.8

Perhaps the most significant contrast with the doctrine of Original Sin lies in the Jewish concept of Teshuvah (literally “return”).8 Teshuvah represents the belief in the constant possibility of repentance, atonement, and restoration of the relationship with God and fellow human beings. It is a multi-step process typically involving recognition of the wrongdoing, sincere remorse, cessation of the harmful behavior, confession (often directly to God, or to the wronged party), and a firm resolve not to repeat the sin.8 Crucially, Teshuvah emphasizes the individual’s active role in the process of reconciliation. While divine mercy is essential, atonement is achieved through personal effort, growth, and change, without the requirement of a mediating savior figure to pay an inherited debt.36 This stands in sharp contrast to theological systems predicated on Original Sin, where humanity’s inherent corruption and guilt necessitate an external act of redemption, primarily through the atoning sacrifice of Christ.4 Teshuva is about growth, and one can grow from both doing good, and from evaluating wrong paths. In Hebrew, there is no word for sin. Chet (commonly the nearest Hebrew word to sin) means missing, as in missing the target, so jews see Teshuva as an endeavour to evaluate the miss (tshuva) and recalculate a better route. 124

This Jewish framework, built on the foundations of innate purity, free will, the nuanced understanding of the Yetzer Hara and Yetzer Tov, and the transformative power of Teshuvah, presents a fundamentally different anthropology than that derived from Augustinian Original Sin.8 Where the latter often emphasizes human depravity, bondage of the will, and the need for external redemption from an inherited condition, the former stresses human potential, moral agency, the possibility of mastering one’s inclinations, and the capacity for self-initiated return and reconciliation.6 This contrast fosters distinct psychological and ethical landscapes: one potentially burdened by inherent guilt and a sense of fundamental flawedness, the other characterized by a dynamic struggle but underpinned by an optimism about human capacity for good and the ever-present path of repentance.

IV. Psychoanalytic Readings of Guilt, Faith, and Mortification

Psychoanalysis, originating with Sigmund Freud and evolving through figures like Melanie Klein and Jacques Lacan, offers a distinct lens for interpreting religious doctrines like Original Sin and associated phenomena such as guilt and acts of expiation. By exploring the dynamics of the unconscious, internal conflicts, and early developmental experiences, psychoanalytic theory provides frameworks for understanding the psychological underpinnings and functions of religious beliefs and practices.

A. The Psyche’s Burden: Guilt, the Superego, and Religion

Guilt is a central preoccupation in psychoanalytic thought, viewed not merely as a conscious response to wrongdoing but as a complex affective state rooted in the structure and conflicts of the psyche.

Freud: In Freud’s classical model, the psyche comprises the Id (instinctual drives, operating on the pleasure principle), the Ego (mediator with reality), and the Superego (internalized moral authority).22 The Superego develops primarily through the resolution of the Oedipus complex, internalizing parental prohibitions and societal norms.22 Guilt arises from the tension between the Id’s forbidden aggressive and libidinal desires (particularly Oedipal desires directed towards parents) and the Superego’s condemnation.22 This guilt can be conscious but is often unconscious, manifesting as a “need for punishment” or generalized anxiety.22 Freud famously viewed religion as a collective “illusion” or “universal obsessional neurosis”.63 He argued it stems from infantile helplessness (longing for a protective father figure, projected onto God), the unresolved Oedipal complex (God as the exalted father, religious rituals as ways to manage ambivalent feelings towards him), and the need to manage primal instincts repressed by civilization.23 In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud posited that civilization demands the renunciation of instinctual gratification (both sexual and aggressive), and the aggression that cannot be turned outward is turned inward, forming the punitive Superego and generating a pervasive sense of guilt – the fundamental “discontent” of civilized life.63

Klein: Melanie Klein, a pioneer of object relations theory, located the origins of guilt much earlier in infancy.76 She emphasized the infant’s relationship with primary “objects” (initially part-objects like the mother’s breast).76 Klein theorized two fundamental early mental states: the paranoid-schizoid position (characterized by splitting objects into ‘good’ and ‘bad’, projection, and persecutory anxiety) and the later depressive position.76 For Klein, the Superego begins to form much earlier and is initially far harsher than Freud proposed, shaped by the projection of the infant’s own innate aggressive impulses (linked to the death instinct, Thanatos) onto internalized objects.76 Guilt proper emerges in the depressive position, when the infant begins to perceive the mother as a whole object and experiences anxiety and remorse over its own fantasized sadistic attacks against her (the loved object). This “depressive guilt” motivates a desire for reparation – to make amends and restore the good object.76

Lacan: Jacques Lacan, focusing on the structure of the unconscious as akin to language and the subject’s formation within the Symbolic order, offered a different perspective.62 While engaging deeply with Freud, Lacan viewed guilt not necessarily as a direct result of transgression but potentially as a structural element of subjectivity or even a defense mechanism.21 Guilt can function to give consistency to the subject or to manage the anxiety arising from the encounter with the Real or the lack inherent in desire.21

Across these varying psychoanalytic perspectives, a common thread emerges: guilt is fundamentally understood as arising from internal conflict rather than solely from external rule-breaking. For Freud, it’s the clash between instinctual drives and internalized authority 22; for Klein, it’s the tension between love and innate destructiveness directed towards the loved object.76 This internal origin, rooted in unconscious desires, fantasies, and developmental stages, helps explain why guilt can often feel pervasive, irrational, or disproportionate to conscious actions.

Consequently, psychoanalysis tends to interpret religious phenomena, including doctrines like Original Sin, not as literal truths but as complex psychic structures. Religious beliefs and practices are seen as expressions of, or attempts to manage, fundamental psychological dynamics: the longing for parental protection stemming from infantile helplessness, the ambivalent feelings of the Oedipal conflict, the need to regulate guilt arising from internal conflicts, the desire for meaning and order in the face of mortality and the inherent “lack” in existence.23 Religious narratives and rituals provide frameworks for containing anxiety, structuring desire, and offering symbolic resolutions to these deep-seated psychic tensions.63

B. Interpreting Original Sin

Applying these psychoanalytic frameworks to the doctrine of Original Sin yields several interpretive possibilities, treating the narrative not as history but as a myth encoding psychological realities.

- Freudian Lens: The story of Adam’s disobedience against God’s prohibition readily maps onto the Oedipal drama. God represents the primal father figure whose command is transgressed. The “sin” is the symbolic rebellion against this authority, driven by underlying desires (represented perhaps by the desire for forbidden knowledge or power). The resulting guilt is then inherited, mirroring Freud’s controversial notion in Totem and Taboo of inherited guilt from the primal horde’s murder of the father.63 Christ’s atonement can then be seen as a symbolic means of resolving this primordial Oedipal guilt.82

- Kleinian/Object Relations Lens: The narrative can also be read through a pre-Oedipal lens. The Garden of Eden might symbolize the fantasied state of primal unity with the mother (the primary object). Expulsion from the Garden represents the traumatic experience of separation and object loss, a fundamental narcissistic injury.84 The attainment of “knowledge of good and evil” could signify the infant’s entry into the depressive position – the dawning awareness of separateness, the distinction between self and other, and the painful recognition of ambivalence (love and hate) towards the object, leading to guilt over destructive phantasies.76

- Lacanian Lens: From a Lacanian perspective, the Garden represents the pre-Symbolic state of imaginary fullness (the Real). The prohibition (“Do not eat”) establishes the Law of the Father and introduces lack into this realm. The forbidden fruit symbolizes the objet petit a, the unattainable object cause of desire. Eating the fruit signifies the subject’s entry into the Symbolic order (language), which involves an inherent alienation or “sin” – a separation from the Real and the acceptance of castration (the fundamental lack).82 Lacan’s own reference to an “original sin” within psychoanalysis itself points to the foundational role of lack and negativity (stemming from Freud’s own unsatisfied desire, perhaps) in the very possibility of symbolization, language, and the constitution of the subject.82

- Ricoeur’s Symbolic Approach: Philosopher Paul Ricoeur, employing hermeneutics informed by psychoanalysis, analyzes the Adamic myth as a primary symbol through which cultures articulate the experience of evil.87 He traces a progression in the “symbolics of evil” from external defilement, through sin as rupture of a covenant, to internalized guilt.87 The Adamic myth, for Ricoeur, is crucial because it portrays evil not as an ontological necessity (a flaw inherent in finitude) but as a contingent historical event, a “fall” resulting from a misuse of freedom.90 It symbolizes the rupture between human essence (potential goodness) and existence (actual fallenness), expressing the experience of a “servile will” bound by its own bad choices.90 “The symbol gives rise to thought,” allowing reflection on the nature of fault and responsibility.87

These interpretations converge on understanding the Original Sin narrative as a powerful myth that resonates with deep psychological structures and developmental processes.82 Whether focusing on Oedipal conflicts, early object relations, or the entry into language and lack, these readings see the myth as articulating fundamental truths about the human condition – the nature of desire, the origins of guilt, the experience of loss and separation, and the complexities of self-consciousness – even when rejecting its literal historicity.

C. The Logic of Expiation: Corporal Mortification

Acts of expiation, particularly extreme forms like corporal mortification, have a long history within Christian asceticism.24 Practices such as self-flagellation (using the “discipline”), wearing abrasive hairshirts or sackcloth, prolonged fasting, sleep deprivation, and other forms of self-inflicted hardship were employed by figures ranging from desert hermits to medieval mystics (like Catherine of Siena and Henry Suso) and founders of religious orders (like St. Ignatius).24 The conscious motivations often cited include imitating the physical sufferings of Christ (imitatio Christi), performing penance for sins, subjugating bodily desires (“mortifying the flesh”) deemed sinful or distracting, and striving for spiritual purification and union with God.24 The Church’s attitude towards these practices was often ambivalent, sometimes encouraging them as signs of piety while also warning against excess and potential pathology, emphasizing the need for prudence and spiritual guidance.24

Psychoanalysis offers several interpretive frameworks for understanding the underlying psychological dynamics of such practices:

- Guilt and Self-Punishment: The most direct link is to the unconscious need for punishment driven by guilt.22 The Superego, acting as an internalized judge, demands suffering as atonement for transgressions, whether real or imagined (rooted in forbidden desires or aggressive impulses).22 Corporal mortification provides a concrete, physical enactment of this self-punishment, a way to appease the demands of a harsh inner critic.22 The religious framework of penance provides justification and structure for these powerful, often unconscious, punitive drives.24

- Masochism: Freud’s concept of moral masochism is particularly relevant.103 Here, suffering is not merely endured as punishment but is unconsciously sought out, providing a paradoxical form of satisfaction linked to the death drive (Thanatos) turned inward against the self, often intertwined with guilt.103 Extreme ascetic practices, where pain seems pursued for its own sake or far exceeds rational disciplinary goals, can be interpreted as manifestations of moral masochism.103 This distinguishes potentially pathological self-harm from disciplined self-denial, although the line can be blurred.

- Control and Agency: Paradoxically, inflicting pain upon oneself can be an attempt to assert control.99 In situations where individuals feel powerless against external forces or overwhelming internal states (like intense anxiety or unruly desires), self-mortification can create a sphere of action where the individual is the agent of their own suffering. This might be particularly relevant for individuals in highly constrained environments, such as medieval nuns like Catherine of Siena, for whom the body became a primary site of contested agency.99

- Defense Mechanism: Self-inflicted physical pain might serve as a defense against unbearable psychic pain, fragmentation, or overwhelming affects.76 Focusing on tangible, self-controlled physical suffering could distract from or provide a structure for managing chaotic or terrifying internal experiences, such as the persecutory anxieties described by Klein.76

Therefore, psychoanalytically, extreme acts of corporal mortification, while framed religiously as piety or penance, can be understood as complex psychological phenomena. They often represent attempts to appease a pathologically severe Superego, driven by profound, perhaps unconscious, guilt.22 Furthermore, these practices exist on a spectrum that can shade into moral masochism, where suffering itself becomes unconsciously desired or serves defensive purposes beyond the consciously stated spiritual aims.103 The very intensity and potential self-destructiveness observed in some historical examples 97, along with the historical recognition by spiritual directors of the need for moderation 102, point towards the complex interplay of conscious religious motivation and powerful unconscious dynamics in these extreme forms of expiation.

V. The Societal and Psychological Toll

The doctrine of Original Sin, particularly in its influential Augustinian formulation, has not merely shaped theological debates but has also exerted a profound and often burdensome influence on Western culture and individual psychology. Its emphasis on inherent human flawedness and guilt has contributed to specific cultural patterns and potential psychological vulnerabilities.

A. Cultures of Guilt and Shame

Anthropologists and cultural historians often distinguish between “guilt cultures” and “shame cultures” as ways of understanding primary modes of social control and moral orientation.11 Guilt cultures tend to emphasize internalized conscience, individual responsibility, and transgression against abstract laws or principles. Moral control operates primarily through the internal feeling of guilt, regardless of whether the transgression is known to others.12 Shame cultures, conversely, rely more heavily on external sanctions, such as community disapproval, ridicule, or loss of honor/face. Maintaining social standing and avoiding public disgrace are primary motivators.12 While this distinction can be overly simplistic and cultures often exhibit elements of both, it provides a useful heuristic.35

There is a strong scholarly argument that Western culture, significantly shaped by its Christian heritage, functions predominantly as a guilt culture, and that the doctrine of Original Sin played a crucial role in this development.12 By positing sin not just as an act but as an inherent state or inherited guilt, the doctrine internalizes the source of wrongdoing.5 The problem is not merely external behavior but an intrinsic flaw within the self. This fosters the development of an internal moral monitor – the conscience or, in psychoanalytic terms, the Superego – preoccupied with this innate fallenness and the potential for transgression.16 This aligns closely with the dynamics of a guilt-based system of control, where the locus of moral judgment is internalized.11 Historical analyses frequently link the intensification of guilt-consciousness in the West, particularly during periods like the Reformation and Puritanism, to the pervasive influence of Augustinian theology and its emphasis on human depravity.14

This guilt-centric framework has arguably influenced Western ethics, social norms, and even political philosophy. Ethical systems often prioritize abstract principles, law, and individual conscience over communal harmony or honor.11 Socially, it can contribute to heightened anxiety about wrongdoing, a tendency towards introspection and self-scrutiny, and potentially repressive attitudes towards perceived sources of sin (like bodily desires).13 Politically, a belief in inherent human flawedness can underpin skepticism about human perfectibility and justify coercive measures to maintain social order.9 Even as overt religious belief has declined in some parts of the West, this underlying cultural grammar of guilt may persist in secularized forms, manifesting in anxieties about social justice, historical culpability, or personal failings.118 The doctrine of Original Sin, therefore, can be seen as having provided a powerful theological engine that fueled the development and persistence of guilt as a primary mechanism for social and psychological regulation in the West.12

B. The Individual Psyche

Beyond its broad cultural impact, belief in Original Sin can have significant consequences for the individual’s psychological landscape.

- Self-Worth and Anxiety: The notion of being born inherently sinful, flawed, or guilty can profoundly undermine an individual’s sense of self-worth.30 It fosters a baseline feeling of inadequacy, of being fundamentally “not good enough” before God and perhaps others. This can readily translate into heightened anxiety, particularly moral anxiety – the fear of transgressing internalized standards and incurring punishment, whether divine or from one’s own conscience (Superego).32 The constant awareness of an innate propensity towards evil can create a state of perpetual vigilance and self-doubt.

- Repression and Sexuality: As discussed earlier (Section II.B), Augustine’s linking of Original Sin’s transmission to concupiscence embedded a negativity towards sexuality within the doctrine’s framework.13 This historical association has contributed to cultures and individuals viewing sexual desire with suspicion, associating it with the fallen, sinful aspect of human nature.10 Such views can lead to the repression of natural sexual feelings, generating anxiety, guilt, and shame surrounding sexuality, and fostering a mind-body dualism where the body and its desires are seen as inherently problematic.5 Psychoanalytic theory suggests that such repression, while aimed at managing anxiety, often leads to neurotic symptoms or other psychological difficulties.123 Purity culture movements, often rooted in evangelical interpretations of sin, exemplify the potential harms of rigidly policing sexuality based on these theological underpinnings.31

- Mental Health Challenges: Religious frameworks emphasizing intense guilt, inherent sinfulness, divine wrath, and the threat of eternal damnation can, for some individuals, contribute to or exacerbate mental health problems.32 Conditions such as anxiety disorders, depression, and scrupulosity (a form of OCD characterized by religious or moral obsessions and compulsions) have been linked to overly harsh religious upbringings or interpretations focused on sin and judgment.33 The feeling of being spiritually and morally inadequate, coupled with the inability to meet perceived divine standards, can lead to despair and self-loathing.33 In some cases, negative religious experiences centered on sin and guilt can constitute a form of religious trauma.15 While religion can also be a profound source of comfort, meaning, and positive coping mechanisms 119, doctrines like Original Sin, particularly when interpreted rigidly, carry potential psychological risks.

The Jewish perspective, lacking the burden of inherited guilt and viewing the Yetzer Hara as a manageable, even necessary, drive, offers a contrasting psychological potential.8 The emphasis on action, free will, and the ever-available path of Teshuvah may foster greater self-efficacy and reduce the likelihood of pervasive, ontologically rooted guilt.

Ultimately, religious systems built around Original Sin can impose a significant psychological burden, potentially creating a double bind. They posit an inherent flaw or guilt that generates anxiety and low self-worth.1 Simultaneously, the psychological defenses often employed to manage this anxiety or the “sinful” desires associated with the doctrine (such as repression, particularly concerning sexuality 13) can themselves be detrimental to mental health, leading to neurosis, anxiety, or depression.32 The doctrine thus presents a fundamental problem (innate flawedness) for which the common psychological solutions can create further problems, trapping the individual in a cycle of guilt, anxiety, and potentially maladaptive coping mechanisms.

VI. Conclusion: Synthesizing Perspectives on a Burdened Legacy

This inquiry has traversed the complex landscape of the Christian doctrine of Original Sin, examining its theological underpinnings, historical trajectory, comparative dimensions, and psychological resonances. Emerging from specific interpretations of ambiguous scriptural passages, particularly Genesis 3 and Romans 5:12, the doctrine received its definitive Western shape through the work of Augustine of Hippo. His formulation, forged significantly in the crucible of the Pelagian controversy, emphasized inherited guilt (reatum) transmitted biologically via concupiscence, resulting in a weakened human will incapable of achieving good without divine grace.

This Augustinian architecture became foundational for Western Christianity, though interpretations diverged. Catholicism nuanced the concept, emphasizing a “contracted” state of deprivation rather than personal inherited guilt, while maintaining the necessity of baptism and developing doctrines like the Immaculate Conception. Eastern Orthodoxy rejected inherited guilt altogether, formulating the concept of Ancestral Sin focused on inherited mortality and corruption, leading to a more therapeutic understanding of salvation (theosis). Protestantism, while largely accepting Augustine’s premise of Total Depravity, fractured over its implications, with Calvinism stressing divine sovereignty and irresistible grace, and Arminianism/Methodism emphasizing prevenient grace and human response.

Juxtaposed with these Christian frameworks, the Jewish tradition offers a stark counter-narrative. Rejecting inherited guilt, Judaism posits innate human purity, free will, and a dynamic interplay between the good inclination (Yetzer Tov) and the “evil” inclination (Yetzer Hara) – the latter understood not as inherent corruption but as a necessary, albeit potentially unruly, drive. The emphasis falls on individual responsibility for actions and the ever-present path of Teshuvah (repentance), fostering a different anthropological and psychological outlook centered on agency and the potential for restoration.

Psychoanalytic perspectives provide further layers of interpretation. Viewing the Original Sin narrative as a potent myth, psychoanalysis decodes it through lenses of Oedipal conflict (Freud), early object relations and separation anxiety (Klein), or the entry into language and lack (Lacan). Guilt is understood not just as a response to transgression but as arising from deep internal conflicts – between drives and internalized authority, or between love and innate aggression. Religious doctrines and practices, including extreme acts of expiation like corporal mortification, are interpreted as complex psychic phenomena attempting to manage these internal conflicts, appease a punitive Superego, or defend against unbearable affects, sometimes bordering on moral masochism.

Synthesizing these perspectives reveals the significant societal and psychological burdens associated with the doctrine of Original Sin and the intense, pervasive guilt it often cultivates. The theological framework emphasizing inherent human flawedness and/or inherited guilt appears to have been a powerful force in shaping Western culture’s preoccupation with internalized guilt, influencing ethics, social norms, and attitudes towards the body and sexuality.14 On an individual level, this framework carries the potential to negatively impact self-worth, generate significant anxiety, encourage repression (especially regarding sexuality), and, in some interpretations, contribute to mental health challenges.30 The Augustinian legacy, while theologically central for many, is thus ethically and psychologically weighted.

The existence of alternative frameworks, such as the Jewish perspective emphasizing agency, the manageable nature of human drives, and the path of Teshuvah, underscores that the Augustinian interpretation of the human condition is not the only possibility derived from related scriptural traditions.8 These alternatives offer models for understanding wrongdoing and spiritual life that may mitigate the psychological burdens associated with doctrines of innate corruption and inherited guilt.

Ultimately, the doctrine of Original Sin remains a concept of enduring power and consequence. Despite theological critiques and evolving interpretations, its influence persists, woven into the fabric of Western thought, shaping assumptions about human nature, responsibility, and the need for transformation.6 Its legacy is complex – providing a framework for understanding human brokenness and the need for grace for millions, while simultaneously imposing significant psychological and societal burdens rooted in a narrative of inherent flaw and pervasive guilt. Continued critical engagement with the doctrine’s historical formation, its varied interpretations, and its multifaceted impact remains essential for both theological reflection and the pursuit of psychological well-being within the cultures it has profoundly shaped.

Works cited

- Original sin – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Original_sin

- Original Sin: How Original Is It? Romans 5:12 | Answers in Genesis, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://answersingenesis.org/sin/original-sin/how-original-is-it-romans-5-12/

- What Is Original Sin for St Augustine? | TheCollector, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.thecollector.com/st-augustine-original-sin/

- Hans Madueme • Longform Essay • February 17 – Christ Over All, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://christoverall.com/article/longform/original-sin-biological-or-spiritual-problem/

- From Genesis to Judgment: Original Sin Fully Explained – Logos Bible Software, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.logos.com/grow/hall-original-sin/

- Between Choice and Compulsion: An Examination and Critique of the Evolution of ‘Original Sin’ – BearWorks – Missouri State University, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4955&context=theses

- A Study on the Doctrine of Original Sin as the Foundation of Wesleyan Theology – Digital Commons @ George Fox University, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1488&context=dmin

- Jewish views on sin – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_views_on_sin

- ‘Original Sin’: Explaining the Inexplicable – Create a Learning Site, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.wilrens.org/2023/01/cals104/

- Augustine of Hippo – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/augustine/

- Moral Emotions and Moral Behavior – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3083636/

- The Origins of Jewish Guilt: Psychological, Theological, and Cultural Perspectives – PMC, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4560119/

- A Sinful Doctrine?: Sexuality and Gender in Augustine’s Doctrine of Original Sin: Part 1, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://theotherjournal.com/2006/04/a-sinful-doctrine-sexuality-and-gender-in-augustines-doctrine-of-original-sin-part-1/

- MAN’S CHANGING IMAGE OF HIMSELF by Lawrence K . Frank, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.zygonjournal.org/article/12110/galley/24597/download/

- Ways to Sin: Thinking about Hamartiology and Trauma with Moltmann – The Other Journal, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://theotherjournal.com/2022/01/sin-trauma-moltmann/

- Sin: The early history of an idea | Request PDF – ResearchGate, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289833848_Sin_The_early_history_of_an_idea

- Augustine and the Doctrine of Original Sin (Part 2): Background About the Ultimate STD, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.joeledmundanderson.com/augustine-and-the-doctrine-of-original-sin-background-about-the-ultimate-std/

- Eastern Orthodoxy and Original Sin | The Puritan Board, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://puritanboard.com/threads/eastern-orthodoxy-and-original-sin.113755/

- Comparison between Orthodoxy, Protestantism & Roman Catholicism – Christianity in View, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://christianityinview.com/comparison.html

- Total depravity – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Total_depravity

- Guilt, Suffering and the Psyche Alison Jane Hall Middlesex University Doctor of Philosophy February 2010, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://repository.mdx.ac.uk/download/b3dadd64e10335f504e10e370e34c4cfe01b1bc5f21766aae626400ffd5730b6/1234746/PhDAHall.pdf

- Psychoanalysis and the Sense of Guilt.pdf, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.ccc.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-03/Psychoanalysis%20and%20the%20Sense%20of%20Guilt.pdf

- Ambivalence or Melancholia: The Ontogenesis of Religious Sentiment – MDPI, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/15/7/867

- Flagellation | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/religion-and-philosophy/flagellation

- From Death to Depravity: How “Missing the Mark” Became “Original Sin” – ScholarWorks at GSU, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=rs_hontheses

- Where Would We Be Without Genesis 3? Understanding the Significance of Sin, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://christoverall.com/article/longform/where-would-we-be-without-genesis-3-understanding-the-significance-of-sin/

- Original Sin is Unbiblical – Escape to Reality, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://escapetoreality.org/2022/08/03/original-sin-is-unbiblical/

- The origins of original sin for Augustine – Anthony Smith, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.anthonysmith.me.uk/2021/01/29/the-origins-of-original-sin-for-augustine/

- The Original View of Original Sin – Foundations – Vision.org, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://foundations.vision.org/original-view-original-sin-1140

- Original Sin: Inherited Psychological Patterns – :: Forbidden Heights ::, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.forbiddenheights.com/articles/371-original-sin

- Purity Culture and Its Effect on Mental Health – Verywell Mind, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.verywellmind.com/purity-culture-impacts-mental-health-7564315

- Preserving guilt in the “age of psychology”: The curious career of O. Hobart Mowrer, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/features/hop-hop0000045.pdf

- How Religious Groups Can Stigmatize, Mistreat, and Cause Mental Health Conditions, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://lifeafterdogma.org/2022/01/19/religion-stigma-mental-illness/

- Antisemitism and Human Inclinations: The Good and Evil, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.hebraiccommunity.org/midrash/antisemitism-and-human-inclinations-the-good-and-evil/

- Culture of Shame / Culture of Guilt, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://ub01.uni-tuebingen.de/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10900/155017/978-3-86269-044-2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- The concept of Yetzer HaRa : r/Judaism – Reddit, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Judaism/comments/1hau4pe/the_concept_of_yetzer_hara/

- Original Sin in Judaism? : r/AcademicBiblical – Reddit, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/AcademicBiblical/comments/17gksh0/original_sin_in_judaism/

- The Origins of Original Sin: Part IV – Arcane Knowledge, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.arcaneknowledge.org/catholic/original4.htm

- Ancestral Versus Original Sin | St. Mary Orthodox Christian Church …, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.stmaryorthodoxchurch.org/orthodoxy/articles/ancestral_versus_original_sin

- The Doctrine of Original Sin and its Influence on the Theology and Practice of Baptism, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/371593825_The_Doctrine_of_Original_Sin_and_its_Influence_on_the_Theology_and_Practice_of_Baptism

- Understanding Saint Augustine’s Concept of Original Sin – Moody Catholic, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://moodycatholic.com/saint-augustines-original-sin/

- Augustine’s Positive Contributions to Christian Doctrine – Tabletalk Magazine, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://tabletalkmagazine.com/article/2024/02/augustines-positive-contributions-to-christian-doctrine/

- How do the Catholic and Orthodox views of original sin differ? – Christianity Stack Exchange, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://christianity.stackexchange.com/questions/4814/how-do-the-catholic-and-orthodox-views-of-original-sin-differ

- Original sin, control, and divine blame: some critical reflections on the moderate doctrine of original sin | Religious Studies – Cambridge University Press, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/religious-studies/article/original-sin-control-and-divine-blame-some-critical-reflections-on-the-moderate-doctrine-of-original-sin/624408DE1EA64C1CE130754B137D62E6

- why do Catholics and Orthodox have a different opinion on original sin? : r/OrthodoxChristianity – Reddit, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/OrthodoxChristianity/comments/1h0h1on/why_do_catholics_and_orthodox_have_a_different/

- The Ecumenical Stain of Original Sin | Eclectic Orthodoxy – WordPress.com, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2015/09/03/the-ecumenical-stain-of-original-sin/

- Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant Soteriology Compared and Contrasted, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://orthodoxchristiantheology.com/2017/02/09/orthodox-catholic-and-protestant-soteriology-compared-and-contrasted/

- Template:Comparison among Protestants – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Comparison_among_Protestants

- John Calvin’s Doctrines of Grace: Gill’s Defense – Scripture Analysis, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.scriptureanalysis.com/john-calvins-doctrines-of-grace-gills-defense-2/

- Don Stewart :: What Are the Major Protestant Theological Systems: Calvinism, Arminianism, Lutheranism, and Anglicanism? – Blue Letter Bible, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.blueletterbible.org/Comm/stewart_don/faq/bible-basics/question20-what-are-the-major-protestant-theological-systems.cfm

- Six Views on “Original Sin” vs. “Original Guilt” – Society of Evangelical Arminians, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://evangelicalarminians.org/six-views-on-original-sin-vs-original-guilt/

- Introductory and Historical Questions About Arminianism – Thoughts Theological, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.thoughtstheological.com/introductory-and-historical-questions-about-arminianism/

- X-Calvinist Corner – Arminian Perspectives – WordPress.com, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://arminianperspectives.wordpress.com/x-calvinist-corner/

- aspects of arminian soteriology in methodist-lutheran ecumenical dialogues in 20th and 21st – Helda, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstreams/d6ef68a9-6702-4102-8e7e-3f91fee050ba/download

- Yetzer hara – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yetzer_hara

- Exposition (Unpacking Select Passages) – The Back of My Mind, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://gpront.blog/category/theology/exposition-unpacking-select-passages/

- The Evil Inclination (Yetzer Hara) – Rabbi Josh Franklin, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://www.rabbijoshfranklin.com/rabbifranklinblog/2013/05/yetzer-hara-evil-inclination.html

- The Evil Inclination – Jewish Ideas Daily, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://www.jewishideasdaily.com/1017/features/the-evil-inclination/

- Yetzer Tov and Yetzer HaRa: Working Together – Congregation Brit Shalom, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.britshalomstatecollege.org/torah-commentaries/2016/11/30/yetzer-tov-and-yetzer-hara-working-together

- The Yetzer HaRa and the Yetzer HaTov Revisited – Rabbi Josh Franklin, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.rabbijoshfranklin.com/rabbifranklinblog/2022/3/16/the-yetzer-hara-and-the-yetzer-hatov-revisited

- Yetzer Hatov | Texts & Source Sheets from Torah, Talmud and Sefaria’s library of Jewish sources., accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.sefaria.org/topics/yetzer-hatov

- Psychoanalysis – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychoanalysis

- Civilization and Its Discontents, 1930, by Sigmund Freud, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.sigmundfreud.net/civilization-and-its-discontents.jsp

- Civilization and Its “Malcontent:” Sigmund Freud and the Problem of Guilt, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.equip.org/articles/civilization-and-its-malcontent/

- Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://courses.washington.edu/freudlit/Civilization.Notes.html

- The Unconscious Need for Punishment – York University, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://www.yorku.ca/dcarveth/guilt.html

- Object Relations, Identity Formation, and Transitional Space in Religious Conversion – CUNY Academic Works, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5024&context=gc_etds

- A merican A cademy of Religion Dissertation Series edited by H. Ganse Little, Jr. Number 26 FREUD ON RITUAL Reconstruction and Critique by Volney P. Gay, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://ir.vanderbilt.edu/bitstream/1803/1716/1/Freud_on_Ritual.pdf

- Mass Psychology (Penguin Modern Classics) – YourKnow, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://yourknow.com/uploads/books/5c26457f1cef2.pdf

- Religion, Delusion, and Belief Theme in Civilization and Its Discontents | LitCharts, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.litcharts.com/lit/civilization-and-its-discontents/themes/religion-delusion-and-belief

- Sigmund Freud: Religion | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://iep.utm.edu/freud-r/

- Freud, Sigmund. Civilization and Its Discontents – Religious Experience Resources – Reviews, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://people.bu.edu/wwildman/relexp/reviews/review_freud02.htm

- Civilization and Its Discontents – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civilization_and_Its_Discontents

- Civilization and Its Discontents (Chapter 5) – Freud and Religion, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/freud-and-religion/civilization-and-its-discontents/5EEDF7F021747D7962528D82C53C5AF9

- Freud, S. (1930). Civilization and its Discontents. The Standard Edition – Penn Arts & Sciences, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Freud_SE_Civ_and_Dis_complete.pdf

- Object Relations Theory | Melanie Klein – Simply Psychology, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.simplypsychology.org/melanie-klein.html

- Child’s Play: Psychoanalysis and the Politics of the Clinic by Carolyn Laubender Program in Literature – DukeSpace, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/bitstreams/34dfe7b3-289e-4ca2-a24a-0c51fbd21ede/download

- (PDF) object relation theory in Ian McEwan’s novel – ResearchGate, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364777068_object_relation_theory_in_Ian_McEwan’s_novel

- Creativity, Femininity, Reparation, Justice Carolyn Laubender In an article titled “The Empty Space,” Da – Free Associations, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://freeassociations.org.uk/FA_New/OJS/index.php/fa/article/download/260/301

- An historical and psychoanalytic investigation with reference to the bride-in-white Gavin Williams – Goldsmiths Research Online, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://research.gold.ac.uk/8044/1/PACE_thesis_Williams_2012.pdf

- Interpreting Interpretation in Psychoanalysis: Freud, Klein, and Lacan – Duquesne Scholarship Collection, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://dsc.duq.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1646&context=etd

- (PDF) original sin, the symbolization of desire, and the development of mind: A psychoanalytic gloss on the Garden of Eden – ResearchGate, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334598194_original_sin_the_symbolization_of_desire_and_the_development_of_mind_A_psychoanalytic_gloss_on_the_Garden_of_Eden

- Lacanian Psychoanalytic Explorations of Love within Christianity and Islam, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/articles/lacanian-psychoanalytic-explorations-of-love-within-christianity-and-islam/

- Névrose, Œdipe et blessure narcissique – ResearchGate, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247912667_Nevrose_OEdipe_et_blessure_narcissique

- KLEINIAN PSYCHODYNAMICS AND RELIGIOUS ASPECTS OF HATRED AS A DEFENSE MECHANISM – St. Michael’s Institute, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://www.saintmichael.net/kleinian-psychodynamics-and-religious-aspects-of-hatred-as-a-defense-mechanism.html

- The Tragic Man of Heinz Kohut:, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.isfo.it/files/File/Adamo%2050%20Jubelee/4.Babu.pdf

- The Symbolism of Evil: Paul Ricoeur, Emerson Buchanan: 9780807015674 – Amazon.com, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Symbolism-Evil-Paul-Ricoeur/dp/0807015679

- Symbolism of Evil: Ricoeur, Paul: 9780060668273 – Amazon.com, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Symbolism-Evil-Paul-Ricoeur/dp/006066827X

- Book Reviews, Sites, Romance, Fantasy, Fiction | Kirkus Reviews, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/a/paul-ricoeur/the-symbolism-of-evil/

- On the Hermeneutics of Evil | Cairn.info, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://shs.cairn.info/revue-de-metaphysique-et-de-morale-2006-2-page-197?lang=fr

- Finitude and Evil (Chapter 5) – Ricœur at the Limits of Philosophy, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/ricoeur-at-the-limits-of-philosophy/finitude-and-evil/3D26D5E968213C13F584EAE46FA43C3B

- Mariano da Rosa Luiz Carlos, Toexist is to sin? Sin as a rupture between essence and existence: Sin as a Symbol of Evil in Paul Ricoeur and Existential Alienation in Paul Tillich – PhilPapers, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://philpapers.org/rec/LUITIT-2

- Flagellation | Penance, Self-Discipline & Mortification | Britannica, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/flagellation

- Mortification in Catholic theology – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mortification_in_Catholic_theology

- Mortification of the flesh – Wikipedia, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mortification_of_the_flesh

- Penance & Mortification | Saints & Catholic Traditions – Religious Vocation, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.religious-vocation.com/penance_and_mortification.html

- Knowing When to Stop: Corporal Mortification in Late Medieval Europe Reflected in the Lives and Works of Catherine of Siena and Henry Suso – Emma Mavin, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.emmamavin.com/knowing-when-to-stop-corporal-mortification-in-late-medieval-europe-reflected-in-the-lives-and-works-of-catherine-of-siena-and-henry-suso/

- The Psychoanalytic Approach to Psychosomatics and Eating Disorders – CyberPsych, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.cyberpsych.org/pdg/pdghist.htm

- (PDF) The Body as a Lived Metaphor: Interpreting Catherine of Siena as an Ethical Agent, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249772701_The_Body_as_a_Lived_Metaphor_Interpreting_Catherine_of_Siena_as_an_Ethical_Agent

- “I Desire to Suffer, Lord, because Thou didst Suffer”: Teresa of Avila on Suffering – PMC, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6899697/

- Corporal Penance in Belief and Practice: Medieval Monastic Precedents and Their Reception by the New and Reformed Religious Orders, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://journals.librarypublishing.arizona.edu/uahistjrnl/article/592/galley/579/download/

- Self-mortification must be moderate, monitored | National Catholic Reporter, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.ncronline.org/news/vatican/self-mortification-must-be-moderate-monitored

- Freud and Masochism – European Journal of Psychoanalysis, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/articles/freud-and-masochism/

- Death and desire _ psychoanalytic theory in Lacan_s return to Freud – Penn Arts & Sciences, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Boothby_Enigma_of_Death_Drive.pdf

- Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association | Volume 32 (1984) – PEP | Browse, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://pep-web.org/browse/apa/volumes/32

- Demystifying A Sexual Perversion: An Existential Reading of Sadomasochism and Erich Fromm’s Call to Love – Duquesne Scholarship Collection, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://dsc.duq.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2024&context=etd

- Masochism and literature, with reference to selected literary texts from Sacher-Masoch to Duras. – CORE, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30695689.pdf

- ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF MASOCHISM – Brill, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://brill.com/downloadpdf/display/title/30313.pdf

- Teaching Medieval Italian Women Writers – This Rough Magic, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://www.thisroughmagic.org/Grossvogel%20TRM.pdf

- Cultural Models of Shame and Guilt – Positive Emotion and Psychopathology Lab, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://www.gruberpeplab.com/teaching/psych3131_summer2015/documents/3.2_WongTsai_2007_CultureShameGuilt.pdf

- The Origins of Guilt-Shame-Fear, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://honorshame.com/the-origins-of-guilt-shame-fear/

- (PDF) Shame Cultures, Fear Cultures, and Guilt Cultures: Reviewing the Evidence – ResearchGate, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327796897_Shame_Cultures_Fear_Cultures_and_Guilt_Cultures_Reviewing_the_Evidence

- Hannes Wiher Shame and Guilt: A Key to Cross-Cultural Ministry – World Evangelical Alliance, accessed on April 21, 2025, http://www.worldevangelicals.org/resources/rfiles/res3_234_link_1292694440.pdf

- Shame in early modern thought by Hannah Dawson – Author’s Accepted Manuscript for History of European Ideas 2018, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/103923865/Shame_in_early_modern_thought_by_Hannah_Dawson_Author_s_Accepted_Manuscript_for_History_of_European_Ideas_2018.pdf

- The Good News for Honor-Shame Cultures – Lausanne Movement, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://lausanne.org/global-analysis/the-good-news-for-honor-shame-cultures

- Culture of Shame / Culture of Guilt – Theological Commission, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://theology.worldea.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/WoT_06-Thomas_Schirrmacher-Culture_of_Shame_or_Guilt.pdf

- Holy Children are Happy Children: Jonathan Edwards and Puritan Childhood Russ Allen Master of Arts in History Thesis Director: – Scholars Crossing, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1401&context=masters

- The Secularisation of Sin in the Nineteenth Century | The Journal of Ecclesiastical History | Cambridge Core, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-ecclesiastical-history/article/secularisation-of-sin-in-the-nineteenth-century/4ED6C734D21D67AB8299BA66C255B49B

- Religion and mental health – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3705681/

- Unsettling Theology: Decolonizing Western Interpretations of Original Sin by Melanie Kampen – UWSpace – University of Waterloo, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://www.uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstreams/1e6039dc-9bd8-4d0e-9468-dfb8b896b27e/download

- FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO COLLECTIVE GUILT – HOW WESTERN CIVILIZATION IS EMBRACING A NARRATIVE THAT COULD DESTROY IT | Hungarian Review, accessed on April 21, 2025, https://hungarianreview.com/article/20210325_from_original_sin_to_collective_guilt_-_how_western_civilization_is_embracing_a_narrative_that_could_destroy_it/